- The protozoan Entamoeba histolytica is responsible for intestinal amebiasis as well as extraintestinal symptoms.

- Despite the fact that 90% of E. histolytica infections are asymptomatic, about 50,000,000 people become symptomatic each year, and around 100,000 people each year pass away as a direct result of their illness.

- In this exercise, you will learn about the examination and treatment of amebiasis caused by Entamoeba histolytica, with an emphasis on the function of the interdisciplinary team.

- Intestinal amebiasis is caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica, which can also appear in other parts of the body.

- In spite of the fact that 90% of E. histolytica infections are asymptomatic, almost 50,000,000 people develop symptoms and about 100,000 die every year as a direct result of this bacteria.

- In countries with weaker economic infrastructure, amebic diseases are more common.

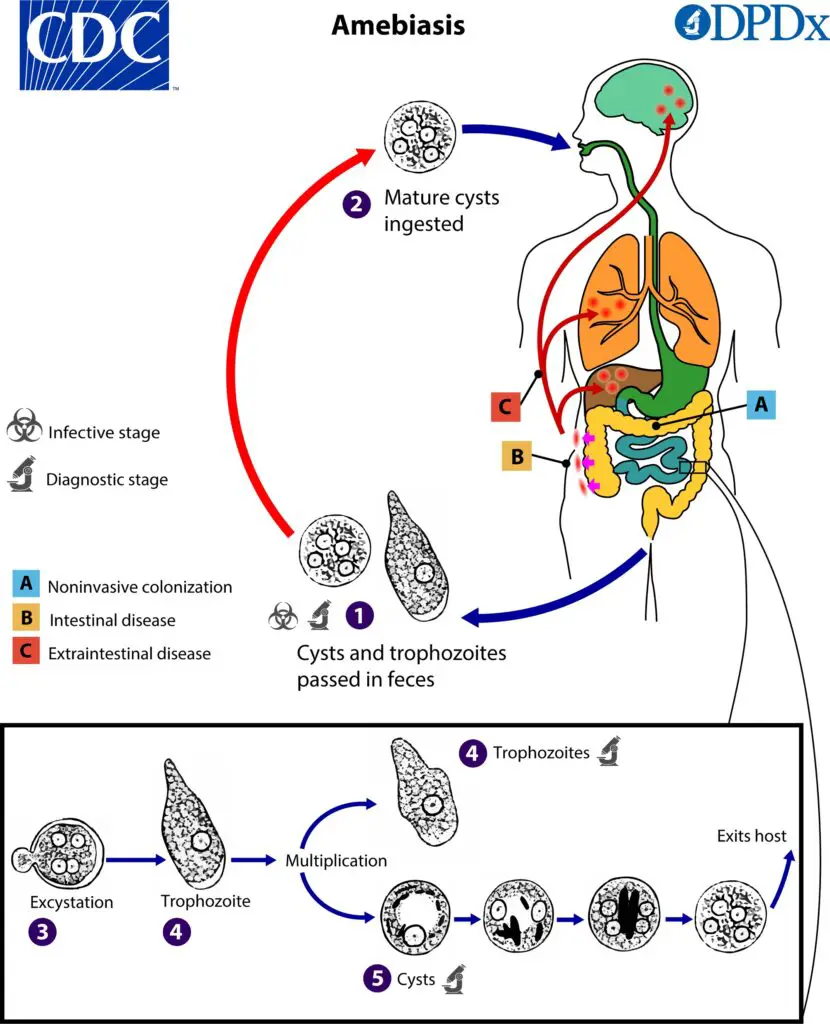

- Amebic cysts of Entamoeba histolytica are ingested via fecal-oral contact, most commonly through tainted food or water.

What is Gastrointestinal Amebiasis?

- Gastrointestinal amebiasis, also known as amoebic dysentery, is an infection of the large intestine caused by microscopic, single-celled parasites called amoebas, specifically Entamoeba histolytica. These parasites primarily thrive in the human colon and are transmitted through contaminated water supplies or food contaminated with human waste.

- Areas where human waste is used as fertilizer are particularly at risk of contamination by the parasite. Additionally, individuals infected with E. histolytica who do not regularly and properly wash their hands can spread the germs, facilitating the transmission of the infection.

- Once ingested, the amoebas enter the body through the mouth and eventually settle in the large intestine. In most cases, the parasites present in the colon are harmless (Entamoeba dispar). However, E. histolytica, if it invades other organs, poses a significant health risk.

- Amoebic dysentery occurs when the amoebas penetrate the gut lining, leading to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and in severe cases, ulcers and bleeding. In some instances, the amoebas can enter the bloodstream and establish infections in isolated areas of the brain or liver, resulting in abscesses.

- Gastrointestinal amebiasis is more prevalent in tropical regions such as Mexico, India, Central America, South America, Africa, and Asia, where over 10% of the population may be infected. However, cases of amebiasis can also occur in developed nations, particularly among recent immigrants and tourists from countries where amoebas are common.

- Proper sanitation, safe water practices, and good hygiene, including regular handwashing, are important measures for preventing the transmission of gastrointestinal amebiasis. Treatment for amebiasis typically involves medication to eliminate the parasites and alleviate symptoms.

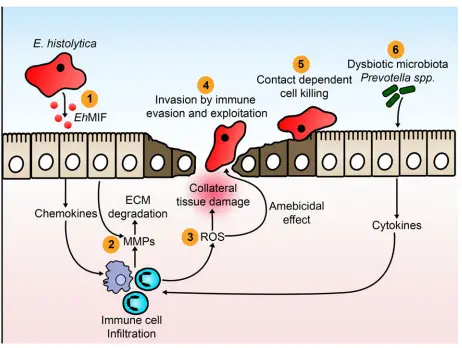

- Secreted E. histolytica macrophage migration inhibitory factor (EhMIF) causes mucosal inflammation.

- Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are upregulated in response to inflammation caused by E. histolytica. MMPs degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) in the intestine, paving the way for cell migration.

- Infiltrating inflammatory cells generate oxygen free radicals (ROS) which are capable of destroying parasites. Collateral tissue damage during an inflammatory period is also caused by oxygen free radicals.

- E. histolytica invades the intestinal mucosa by evading and manipulating the human immune system.

- E. histolytica causes cell death upon contact.

- Elevated amounts of P. copri raises the risk of colitis

Characteristics of Entamoeba histolytica

Entamoeba histolytica is a pseudopod-forming anaerobic protozoan parasite that is responsible for causing amebiasis in humans. Here are some key characteristics of Entamoeba histolytica:

- Mobility: Entamoeba histolytica is actively motile and exhibits movement through crawling or gliding.

- Life Cycle: The parasite exists in three forms: trophozoite, precyst, and cyst.

- Cyst Formation: When immature, the parasite forms cysts with a diameter of 10-16 µm, containing a single nucleus. As the cyst matures, it develops four nuclei.

- Survival and Transmission: The cysts of Entamoeba histolytica can survive in various environments such as soil, water, and especially moist foods. These cysts play a crucial role in the transmission of the parasite.

- Reproduction: Entamoeba histolytica reproduces through binary fission, where a single organism divides into two identical daughter cells.

- Sensitivity to Environmental Factors: Entamoeba histolytica is sensitive to drying, heat, and chemical sterilization. These factors can affect the viability and infectivity of the parasite.

- Temperature Dependency: At low temperatures, the formation of pseudopodia (temporary protrusions used for movement) and motility of Entamoeba histolytica are inhibited.

- Trophozoite Size: The diameter of the trophozoite form of Entamoeba histolytica typically ranges from 10 to 50 µm and contains a single nucleus.

Life Cycle of E. histolytica

- Both a cystic form and a trophozoite form are involved in the infectious life cycle of E. histolytica. The nuclei count in the cyst is four or less, and its diameter is 10-15 m.

- Cysts from fecally contaminated food or water are the most prevalent route of infection with Escherichia histolytica.

- Transmission via oral-anal sexual practises has also been observed. The trophozoites are excysted in the intestinal tract.

- The invasive trophozoite form, about 10-60 m in diameter, has a single nucleus with a central karyosome.

- The intestinal mucin layer is a possible site for cyst formation by trophozoites. The parasite cell surface Gal/GalNAc lectin appears to have a role in quorum sensing during cyst formation.

- Beta-adrenergic receptor 18 signalling and autophagy are two more pathways involved in cyst development (a method of degrading damaged or unnecessary proteins and organelles).

- There are a total of 672 genes that are unique to cysts and 767 genes that are unique to trophozoites.

Gene Structure and Organization

- Genomic organisation and promoter elements of E. histolytica appear to be unique from those of both metazoans and better-characterized protozoa.

- The genome of E. histolytica is projected to have 14 chromosomes and 10,000 genes, with a current estimate placing its size at 24 million base pairs.

- Roughly 20% of the DNA in a cell is ribosomal RNA, and a whopping 10% is made up of tRNA genes arranged in repeated linear arrays.

- Predictions indicate that 30% of genes have introns33 and that 6% of genes have two or more introns. Relatively recently, an expressed sequence tag library was used to study about 7 percent of the putative amebic genes.

- U2, U4, and U5 snRNAs were shown to have molecular evidence supporting their role in splicing, and 60% of introns were shown to have splicing evidence.

- Heterologous gene expression in Escherichia coli via DNA-mediated transfection has been achieved both transiently and persistently. The promoter of the E. histolytica gene producing the heavy subunit of the N-acetyl—Dgalactosamine-specific adhesin has been analysed by deletion and replacement (hgl5).

- Upstream of the transcription start site, a total of 200 bases were analysed, and within that space, four positive upstream regulatory elements and one negative upstream regulatory element were found.

- In two instances, the transcription factors that are responsible for the regulation of genes by these upstream regulatory elements have been isolated.

- There are two novel transcription factors; one has RNA-binding motifs and the other has EF-hand motifs.

- Notably, calcium regulates the ability of the EF-hand containing transcription factor to bind to its homologous DNA motif.

- There are a few core promoter elements that have been shown to regulate gene expression and control the site of transcription initiation. These elements include a TATA element 30 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site, the novel conserved sequence GAAC between the TATA and initiator elements, and the conserved sequence at the transcription start site (putative initiator).

Cell Biology and Biochemistry

- There are no organelles in E. histolytica that resemble the rough endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, or the mitochondria, despite the fact that this organism is a eukaryote.

- It is likely that mitochondria were once present in E. histolytica due to the existence of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes such as pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase and heat shock protein 60 (hsp60).

- The leftover organelles of defunct mitochondria, called mitosomes, have also been discovered.

- Signal sequences are present in cell surface and secreted proteins despite the absence of the rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, and tunicamycin blocks protein glycosylation.

- In the trophozoite’s cytoplasm, the ribosomes have crystallised into aggregated arrays. The E. histolytica genome remarkably contains over a hundred transmembrane kinases.

- These kinases belong to the family of Gal/GalNAc lectin-related proteins, which all share the lectin intermediate (igl) subunit’s CXXC and CXC extracellular patterns.

- To my knowledge, E. histolytica is the only protist that has both the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated serine metabolic pathways.

- For E. histolytica, the cysteine biosynthesis route is also crucial. Amino acids may play a role in ATP creation in E. histolytica, even though the glycolytic route is the primary source of ATP in this organism.

Sources of contamination of Amebiasis

Amebiasis can be sourced from various avenues of contamination. Here are the key sources:

- Contaminated Food and Water: The most common source of amebiasis is the ingestion of food and water contaminated with human feces containing the Entamoeba histolytica cysts.

- Indirect Transmission: The parasite can also be transmitted indirectly through objects or hands contaminated with fecal matter, followed by oral contact with the contaminated hands or objects.

- Resistance to Chlorine: The cysts of Entamoeba histolytica have a certain level of resistance to chlorine, which is commonly used in the treatment of drinking water. This resistance makes it less effective in eliminating the cysts.

- Poor Socio-economic Conditions and Sanitation: A lack of proper sanitation and poor socio-economic conditions contribute significantly to the endemic nature of amebiasis in developing countries such as India, Africa, and parts of Central and South America.

- Migrants and Travelers: Migrants and travelers from endemic areas can bring the parasitic infection to other regions, including the United States, thereby causing sporadic cases of amebiasis in non-endemic countries.

- Asymptomatic Carriers and Food Handlers: Asymptomatic carriers, particularly food handlers who may unknowingly harbor the parasite, can spread the infection through improper hygiene practices during food preparation.

- Consumption of Contaminated Crops and Aquatic Animals: The consumption of food crops and aquatic animals that have been irrigated or come into contact with fecally contaminated water can serve as a route of transmission for amebiasis.

- Sexual Transmission: In some instances, amebiasis has been reported to be transmitted sexually, particularly among individuals engaged in homosexual activities.

Epidemiology

Amebiasis, specifically amoebic dysentery caused by Entamoeba histolytica, has distinct epidemiological characteristics. Here are key points regarding the epidemiology of amebiasis:

- Global Impact: Amoebic dysentery is the third most common parasitic infection worldwide and contributes significantly to mortality and morbidity, particularly in developing countries. Migrants and travelers are often affected by the infection.

- Historical Discovery: Amebiasis was first described in 1875 by Fedor Losch, who isolated the organism from the stool of a farmer in Russia.

- Prevalence in Developing Countries: Amebiasis is more common in developing countries where personal hygiene practices and water supply may be inadequate. Limited access to laboratory facilities can result in misdiagnosis or underreporting of cases.

- Mortality Rate: According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are over 50,000 to 100,000 deaths related to amebiasis worldwide each year. Nutritional status is believed to be a significant factor contributing to the increased mortality rate.

- Invasive Intestinal Amebiasis: Acute amebic dysentery can lead to invasive intestinal amebiasis, with prevalence rates ranging from 2.2% to 16% among affected patients.

- Outbreaks: Amebiasis outbreaks have been reported in various settings. In the early twentieth century, an outbreak occurred in three hotels, likely due to contaminated food handlers. Waterborne outbreaks also occurred in 1934 and 1950 when drinking water became contaminated with fecal-contaminated wastewater.

- Sexual Transmission: There have been reports of amebiasis outbreaks attributed to sexual transmission. This mode of transmission emphasizes the importance of safe sexual practices in preventing the spread of the infection.

Pathogenesis of Amebiasis

The pathogenesis of amebiasis, caused by Entamoeba histolytica, involves a series of events that lead to tissue damage and inflammation. Here are the key points regarding the pathogenesis of amebiasis:

- Infection and Cyst Production: After ingestion, the infection begins when 2000-4000 cysts are produced in the human body within approximately 2 hours.

- Disruption of the Stomach Barrier: E. histolytica infection disrupts the protective mucus coat of the stomach and detaches enterocytes, the cells lining the intestinal wall.

- Penetration and Inflammation: The parasite penetrates the lamina propria, a layer beneath the intestinal epithelium, and triggers inflammation within approximately 4 hours. It releases pro-inflammatory molecules, including interleukin 1 beta, interleukin 6, interleukin 8, interferon-gamma, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

- Tissue Destruction: The virulence of E. histolytica is attributed to its ability to destroy host tissues through the secretion of various molecules. Anchored glycoconjugates on the surface of the parasite cells play a role in the interaction between the host and parasite.

- Interaction with Host Cells: Interaction between polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils and lymphocytes) and E. histolytica trophozoites leads to damage to the intestinal epithelial cells. The parasite degrades the host’s DNA and mitochondria and induces apoptosis (cell death) in the host cells.

- Liver Involvement: In liver abscesses caused by E. histolytica, a strong inflammatory response damages the liver cells. In amebic hepatic abscess, the monocyte locomotion inhibitory factor is responsible for delayed inflammation.

- Virulence Factors: Three main virulence protein factors contribute to the pathogenesis of E. histolytica. These include Gal-lectin, cysteine proteinase, and amebapores, which aid in host tissue destruction and immune modulation.

Detection of Amebiasis

Microscopy

- E. histolytica-specific diagnostic assays are superior to microscopic identification of the parasite in stool, liver abscess pus, or colonic biopsies (see following discussion).

- Although E. histolytica is more likely to be the cause of erythrophagocytic amebae, E. dispar trophozoites have been discovered to include eaten red blood cells as well.

- Only between 8 and 44 percent of patients with amebic liver abscess had the parasite detected through repeated stool investigations.

- Despite best efforts, identifying the parasite in aspirated pus from liver abscesses has a 20% sensitivity rate even in the most skilled hands.

Antigen Detection

- To far, the only faecal antigen test that can reliably differentiate between E. histolytica, E. dispar, and E. moshkovskii is the TechLab E. histolytica II enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

- Numerous investigations in both E. histolytica endemic and nonendemic regions have demonstrated the sensitivity and specificity of a test based on the identification of the Gal/ GalNAc lectin in stool, while a single study has reported a discrepancy between PCR and antigen detection.

- Amebic liver abscess can also be diagnosed with the help of antigen detection. Before undergoing antiamebic treatment, 96% (22/23) of patients with amebic liver abscess had Gal/GalNAc lectin in their serum, according to a study. If the parasite was present in pus from a liver abscess, then the detection rate was between 41% and 74%.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- Comparable sensitivity to that of stool antigen detection can be achieved with real-time PCR (qPCR).

- When it comes to detecting E. histolytica DNA in bodily fluids like stool and liver abscess pus, qPCR is a more sensitive assay than standard PCR.

- Differentiating E. histolytica isolates using PCR might be valuable for epidemiological studies and for elucidating the virulence characteristics of individual isolates.

Serology

- For the diagnosis of amebic liver abscess and amebic colitis, the IHA test for anti-amebic antibody has a sensitivity of 70% in the beginning of the illness and increases to greater than 95% after recovery.

- Current serologic assays suffer from the problem of being persistently positive for years after an episode of amebiasis has resolved.

- It follows that between 10% and 35% of people living in underdeveloped nations have anti-amebic antibodies, as measured by standard serologic tests.

- There may be a lack of specificity in serologic tests because most patients with invasive amebiasis in affluent countries are immigrants from developing countries.

- As an illustration, between 80% and 96% of patients in five recent series of amebic liver abscess cases in the United States were foreign-born.

- Therefore, one should not make the diagnosis of amebiasis in a native of a country where amebiasis is endemic on the basis of a serologic test alone, as current serologic assays may be inadequate for the separation of acute from previous amebiasis, even in industrialised nations.

Colonoscopy

- Since the disease may only be present in the cecum or ascending colon, colonoscopy is the preferred diagnostic method.

- Preparing the patient with cathartics or enemas is not recommended since they may obscure the parasite’s true identity.

- Examining and testing for E. histolytica antigen in wet preparations of material aspirated or scraped from the base of ulcers is recommended.

- Granular, friable, and diffusely ulcerated mucosa may characterise amebic colitis, a condition that can superficially resemble inflammatory bowel disease.

- Pseudomembranes and large geographic ulcers may also be present. Histopathologic analysis of colonic biopsy specimens from individuals with amebic colitis has a detection rate of 0% to 100% of trophozoites, depending on the study.

- Take biopsy samples from the ulcers’ borders. Staining parasites with periodic acid-Schiff makes them more visible in biopsies because of their distinctive magenta hue.

- It has been established that E. histolytica can infiltrate carcinomas, leading to misdiagnosis.

Imaging Procedures

- In order to diagnose amebic abscesses in the liver, any of the three most used diagnostic modalities—ultrasound, CT, or MRI—are equally effective.

- An amebic abscess cannot be distinguished from a pyogenic abscess using any of the three methods.

- Six months after treatment, only one-third to two-thirds of amebic liver abscesses were resolved on repeat ultrasonography.

Clinical manifestation of Amebiasis

Amebiasis, caused by Entamoeba histolytica, can manifest with various clinical presentations. Here are the key manifestations of amebiasis:

- Asymptomatic Infection: Approximately 80% of E. histolytica infections are asymptomatic, with the parasite persisting in the colon without causing noticeable symptoms. However, asymptomatic carriers can still pose a risk of transmitting the infection to others.

- Intestinal Amebiasis: Symptoms typically develop after two to four weeks of infection. Common manifestations include profuse diarrhea, mild fever, abdominal pain, and cramps. In some cases, intestinal amebiasis can become chronic, leading to vague gastrointestinal distress, blood and mucus in the stool, severe ulceration of the colonic mucosa, and rarely, intestinal obstruction due to the presence of trophozoite masses.

- Variation in Symptoms: Clinical symptoms can vary depending on host factors and the stage of the parasite. The severity and duration of symptoms can differ from person to person.

- Amoebic Dysentery: Invasive infection by trophozoites can cause amoebic dysentery, which is a severe form of amebiasis. Symptoms include diarrhea with blood and mucus, stomach pain, weight loss, fever, and chills.

- Extraintestinal Infections: In some cases, trophozoites can invade the intestinal wall, disseminate via the bloodstream, and cause amoebic abscesses in extraintestinal tissues. Common sites of infection include the liver and brain, leading to liver and brain abscesses. Other manifestations may include peritonitis, pleuropulmonary abscesses, and cutaneous and genital amoebic lesions.

- Hepatic Amebiasis: Hepatic amoebiasis is a common complication when trophozoites spread from the intestinal mucosa to the liver through the bloodstream. Symptoms may include fever, weakness, abdominal swelling, nausea, jaundice, cough, and upper-right quadrant pain. These symptoms can persist for several weeks.

Treatment of Amebiasis

The treatment of amebiasis, caused by Entamoeba histolytica, depends on the type and severity of the infection. Here are the key treatment approaches for amebiasis:

- Asymptomatic Intestinal Infection: Asymptomatic carriers with intestinal infection can be treated with medications such as paromomycin or diloxanide furoate. These drugs help eliminate the parasite from the intestines.

- Intestinal and Extraintestinal Infections: Both intestinal and extraintestinal infections can be treated with metronidazole or other 5-nitroimidazole medications. These drugs are effective in killing the parasite and are commonly used as the first-line treatment for amebiasis.

- Amoebic Liver Abscesses: In the case of amoebic liver abscesses, therapeutic aspiration may be recommended. This involves draining the abscess under medical supervision. If there is no improvement with oral therapy, therapeutic aspiration becomes necessary to relieve symptoms and promote healing.

- Fulminant Colitis or Abscess Drainage: In severe cases of fulminant colitis or when there is an abscess, broad-spectrum antibiotics may be required. The choice of antibiotics depends on the specific situation and should be determined by a healthcare professional. Abscess drainage may also be performed as part of the treatment approach.

Prevention and control measures of Amebiasis

Prevention and control measures are crucial in reducing the transmission and impact of amebiasis. Here are key measures for the prevention and control of amebiasis:

- Safe Drinking Water: Implement conventional drinking water treatment methods such as sedimentation, coagulation, filtration, and the use of disinfectants to ensure the safety of drinking water. Chlorination may not be sufficient to kill amebic cysts, so alternative methods like heat treatment or the use of iodine at appropriate concentrations should be considered.

- Proper Food Handling and Preparation: Heat treatment of food at 68°C (154°F) for 5 minutes is effective in killing amebic cysts. It is essential to properly cook food, especially fruits and vegetables that may come into contact with fecally contaminated soil. Thoroughly clean and disinfect produce before consumption.

- Avoid Consumption of Contaminated Food and Water: Travelers should exercise caution when visiting endemic regions by avoiding the consumption of undercooked food and untreated water. Safe food and water practices, such as choosing boiled or bottled water and eating well-cooked food, should be followed.

- Hygiene and Sanitation: Good personal hygiene, including regular handwashing with soap and clean water, is crucial in preventing the spread of amebiasis. Proper sanitation facilities and practices, such as the safe disposal of fecal waste, are important in reducing the contamination of water sources and food.

- Prohibition of Food Handling by Infected Individuals: Asymptomatic carriers can shed millions of amebic cysts per day for extended periods. People with amoebic infections should be prohibited from food preparation and handling to prevent the contamination of food and the transmission of the infection.

- Health Education and Awareness: Public health campaigns should promote awareness about the risk factors, symptoms, and preventive measures of amebiasis. Providing education on proper hygiene practices, safe food and water handling, and the importance of sanitation can help reduce the incidence of the infection.

E. histolytica infections

While the vast majority of people who become infected with E. histolytica show no symptoms at all, as many as 10% of those people may eventually become ill. Although E. histolytica most often affects the intestines, it can also harm the liver, lungs, heart, and brain.

- Gastrointestinal: Symptoms of gastrointestinal issues normally develop slowly over a period of one to three weeks. Common symptoms include diarrhoea, bloody stools, weight loss, and stomach pain.

- Liver: Amoebic liver abscess is the most prevalent extraintestinal consequence. Months to years after visiting an endemic region, symptoms may begin to appear. High body temperature and pain in the upper right quadrant are symptoms. Hepatomegaly and soreness of the liver may be present on physical examination. Less than 10 percent of patients exhibit jaundice. Leukocytosis without eosinophilia, high alkaline phosphatase levels, transaminitis, and an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate are typical laboratory results.

- Respiratory tract: Atelectasis and transudative pleural effusions are the result of pleuropulmonary involvement, an uncommon consequence of the respiratory system. Rupture of an amoebic liver abscess into the pleural space can result in empyema or a hepato-bronchial fistula, both of which can lead to high body temperature, coughing, and difficulty breathing.

- Cardiac infection: This even rarer complication than pleuropulmonary disease occurs when an abscess in the liver ruptures into the pericardium, causing the patient to experience the symptoms of pericarditis or cardiac tamponade.

- Brain infection: Amoebic brain abscesses are an uncommon form of brain infection characterised by the quick onset of severe symptoms, including headache, vomiting, and changes in mental status, and ultimately, death.

FAQ

What is gastrointestinal amebiasis?

Gastrointestinal amebiasis is an infection of the large intestine caused by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica.

How is gastrointestinal amebiasis transmitted?

Gastrointestinal amebiasis is typically transmitted through the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the cysts of Entamoeba histolytica.

What are the common symptoms of gastrointestinal amebiasis?

Common symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain, cramping, fatigue, weight loss, and sometimes fever.

Can gastrointestinal amebiasis be asymptomatic?

Yes, approximately 80% of E. histolytica infections are asymptomatic, but carriers can still transmit the infection to others.

How is gastrointestinal amebiasis diagnosed?

Diagnosis is typically made by examining a stool sample under a microscope to detect the presence of E. histolytica cysts or trophozoites. Serologic tests and imaging studies may also be used.

What is the treatment for gastrointestinal amebiasis?

Treatment usually involves medications such as metronidazole or other 5-nitroimidazoles to eliminate the parasite from the body. Additional medications may be needed for complications like liver abscesses.

Can gastrointestinal amebiasis lead to complications?

Yes, complications can include the formation of liver abscesses, which may require drainage, as well as the spread of the infection to other organs.

How can gastrointestinal amebiasis be prevented?

Prevention involves practicing good hygiene, such as proper handwashing, consuming safe and clean food and water, and improving sanitation conditions.

Who is at risk for gastrointestinal amebiasis?

Individuals living in areas with inadequate sanitation, travelers to endemic regions, and those with weakened immune systems are at higher risk of contracting gastrointestinal amebiasis.

Is there a vaccine available for gastrointestinal amebiasis?

Currently, there is no commercially available vaccine for gastrointestinal amebiasis. Prevention mainly relies on hygiene and sanitation measures.

References

- Ghosh, S., Padalia, J. & Moonah, S. Tissue Destruction Caused by Entamoeba histolytica Parasite: Cell Death, Inflammation, Invasion, and the Gut Microbiome. Curr Clin Micro Rpt 6, 51–57 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40588-019-0113-6

- Chalmers, Rachel. (2014). Entamoeba histolytica. 10.1016/B978-0-12-415846-7.00018-4.

- Peterson, K. M., Singh, U., & Petri, W. A. (2011). Enteric Amebiasis. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice, 614–622. doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-3935-5.00092-6

- La Hoz RM, Morris MI; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Intestinal parasites including Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Giardia, and Microsporidia, Entamoeba histolytica, Strongyloides, Schistosomiasis, and Echinococcus: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019 Sep;33(9):e13618. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13618. Epub 2019 Jun 23. Erratum in: Clin Transplant. 2020 Mar;34(3):e13807. PMID: 31145496.

- Carrero, J. C., Reyes-López, M., Serrano-Luna, J., Shibayama, M., Unzueta, J., León-Sicairos, N., & la Garza, M. de. (2019). Intestinal amoebiasis: 160 years of its first detection and still remains as a health problem in developing countries. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 151358. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2019.151358

- Espinosa-Cantellano M, Martínez-Palomo A. Pathogenesis of intestinal amebiasis: from molecules to disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000 Apr;13(2):318-31. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.2.318. PMID: 10756002; PMCID: PMC100155.

- https://microbenotes.com/gastrointestinal-amebiasis-entamoeba-histolytica/

- https://www.drugs.com/health-guide/gastrointestinal-amebiasis.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/amebiasis/general-info.html