Contents

What do you mean by Chromoblastomycosis (Chromomycosis)?

Chromoblastomycosis, also referred to as chromomycosis, is a chronic fungal infection of the epidermis and subcutaneous tissues. Multiple species of pigmented fungi, including Fonsecaea spp., Phialophora spp., Cladophialophora spp., and others, are responsible for this condition. The term “chromoblastomycosis” refers to the presence of pigmented chromoblasts, which are characteristic pigmented fungal cells.

Chromoblastomycosis is predominantly a tropical and subtropical disease, with a higher prevalence in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia, among others. Typically, it is caused by the traumatizing inoculation of fungal spores into the epidermis, typically from thorny plants, soil, or decaying vegetation. The infection is more prevalent in individuals with prolonged outdoor exposure, such as farmers, agricultural laborers, and those engaged in activities involving soil or organic matter.

The clinical presentation of chromoblastomycosis is marked by cutaneous lesions that evolve slowly. The initial manifestation is a small papule or nodule at the inoculation site, which progressively enlarges and becomes elevated, warty, or cauliflower-like. Lesions may be solitary or multiple and frequently have a verrucous or crusty appearance. They typically affect the lower extremities, but can also affect other areas of the body.

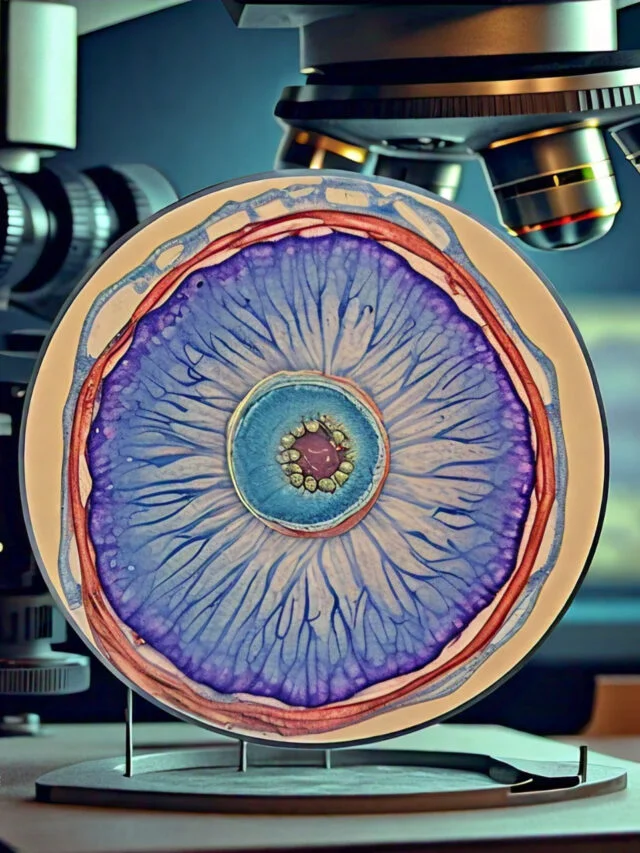

A microscopic examination of infected tissues reveals the presence of pigmented chromoblasts or sclerotic bodies, which are characteristic pigmented fungal cells. These structures represent the fungal elements and are essential for chromoblastomycosis diagnosis.

Chromoblastomycosis can be difficult to treat due to its chronic nature and the fungi’s resistance to numerous antifungal medications. Surgical excision, cryotherapy, heat therapy (hyperthermia), and various antifungal medications, such as itraconazole, terbinafine, and voriconazole, are all viable treatment options. Depending on the severity of the infection and the patient’s response to therapy, the treatment may last several months to years.

Avoid direct contact with soil, decaying vegetation, and potentially contaminated materials to prevent chromoblastomycosis. In order to reduce the risk of infection, it is also essential to practice proper wound care and hygiene.

For an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment of chromoblastomycosis, it is essential to consult with a medical professional or dermatologist.

Causative agents of Chromoblastomycosis (Chromomycosis)

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the epidermis and subcutaneous tissue that is granulomatous and suppurative. The infection is caused by a group of fungi with brown or black pigmentation on their cell walls, known as dematiaceous fungi. These are the most prevalent causes of chromoblastomycosis:

- Fonsecaea pedrosoi: This fungus is one of the most prevalent causes of chromoblastomycosis. It is primarily found in tropical and subtropical regions, where it forms dark, dematiaceous (pigmented) fungal cells.

- Cladophialophora carrionii: Cladophialophora carrionii is another species frequently isolated from chromoblastomycosis cases. It is known to cause chronic cutaneous and subcutaneous infections, as well as generate black cells resembling yeast.

- Phialophora verrucosa: Phialophora verrucosa is a fungus that frequently causes chromoblastomycosis. Its brown to black dematiaceous fungal cells distinguish it.

- Fonsecaea compacta: Fonsecaea compacta is closely related to Fonsecaea pedrosoi and is sometimes associated with chromoblastomycosis. It has comparable characteristics, such as the production of pigmented, dark-colored fungal cells.

- Rhinocladiella aquaspersa: Rhinocladiella aquaspersa is an environmental fungus that can induce chromoblastomycosis. Typically found in soil and decomposing organic matter, this fungus has dark, thick-walled cells.

- Exophiala dermatitidis: Exophiala dermatitidis is a fungus species capable of causing chromoblastomycosis and other opportunistic infections. Typically found in moist environments, this fungus produces yeast-like black cells.

- Exophiala jeanselmei: Exophiala jeanselmei is another species in the genus Exophiala that is associated with chromoblastomycosis. It is found in diverse environmental sources and produces pigmented fungal cells.

- Exophiala spinifera: Exophiala spinifera is a fungal species that is known to induce chromoblastomycosis. It produces melanized, dark-colored fungal cells and is commonly found in soil and plant matter.

Pathogenesis of Chromoblastomycosis (Chromomycosis)

The pathogenesis of chromomycosis, also known as chromoblastomycosis, entails the interaction between the pathogenic fungi and the host immune system. Several key factors contribute to the development and progression of the infection, although the precise mechanisms of pathogenesis are not completely understood.

- Traumatic Inoculation: Chromoblastomycosis typically begins with the traumatic inoculation of fungal spores into the epidermis via minor injuries, such as cuts, scratches, or thorn pricks. Contact with these sources results in the introduction of fungal elements into host tissues.

- Adhesion and Invasion: The fungi responsible for chromoblastomycosis possess adhesion and invasion mechanisms. On the surface of fungal cells, adhesive molecules or structures facilitate attachment to the epidermis or subcutaneous layers. Once affixed, the fungi can penetrate deeper skin layers and cause chronic infections.

- Immune Response: The immune response of the host is essential to the pathogenesis of chromoblastomycosis. Various immune cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, are recruited to the site of infection upon fungal invasion. Using phagocytosis and the release of antimicrobial substances, these immune cells endeavor to eliminate the fungi.

- Granuloma Formation: A granulomatous inflammatory response is triggered in response to persistent fungal presence. Granulomas are constituted of immune cells such as macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes. The formation of granulomas is an effort to contain the infection and restrict the spread of fungi.

- Persistence and Chronicity of Fungi: Despite the immune response, the chromoblastomycosis-causing fungi can evade complete clearance by the host immune system. They are able to adapt and endure within the host’s tissues, resulting in persistent, chronic infections. Fungi can also produce the pigment melanin, which may contribute to their virulence and resistance to host defenses.

- Sporulation and Dissemination: In some instances, fungal organisms within chronic lesions can endure sporulation, resulting in the production of spores. These spores can be released from skin lesions and potentially spread to other portions of the body or to other individuals, although transmission between individuals is uncommon.

Ultimately, the clinical manifestations and outcomes of chromoblastomycosis are determined by the intricate interaction between the fungal pathogens and the host immune response. Chronicity of the infection is a result of the fungi’s ability to persist and cause a chronic inflammatory response. The precise causes of the infection’s persistence and difficulty to eradicate are still under investigation.

It is essential to note that the pathogenesis of chromoblastomycosis may vary slightly depending on the specific fungal species involved.

Risk factors of infection

Several risk factors can increase chromoblastomycosis susceptibility, including:

- Occupation and Environmental Exposure: Those who work or reside in occupations or environments involving direct contact with soil, decomposing vegetation, or organic matter are at a greater risk. This category comprises farmers, agricultural workers, gardeners, construction workers, and rural residents.

- Geographic Location: Tropical and subtropical regions have a higher prevalence of chromoblastomycosis. Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia are regions where the disease is more prevalent. Visiting or living in these regions increases the likelihood of exposure.

- Traumatic Injuries: Infections frequently result from the traumatized introduction of fungal spores into the epidermis. Fungi gain access to the body through traumatic injuries such as cuts, slashes, thorn pricks, and puncture wounds. Occupational or recreational activities involving outdoor exposure and the possibility of skin injuries increase the risk.

- Immunocompromised State: Immunocompromised individuals are more susceptible to chromoblastomycosis, including those with HIV/AIDS, organ transplant recipients, and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. The body’s capacity to control and eradicate the fungal infection is compromised by impaired immune function.

- Genetic Predisposition: Several studies indicate that genetic susceptibility to fungal infections, including chromoblastomycosis, may be influenced by certain genetic factors. Variations in immune response genes may impact an individual’s capacity to effectively eliminate an infection.

- Previous Fungal Infections: Individuals with a history of fungal infections, such as cutaneous candidiasis or dermatophytosis, may be at an increased risk for developing chromoblastomycosis. Prior infections may impair the skin’s protective barrier or predispose individuals to fungal colonization.

- Chronic Lymphedema: Lymphatic obstruction or chronic lymphedema can increase the risk of developing chromoblastomycosis, often due to underlying conditions such as filariasis or surgical interventions. The impaired lymphatic drainage results in fluid accumulation, which may foster the growth and establishment of fungi and infections.

Virulence factors of dematiaceous fungi

Dematiaceous fungi, including those linked to chromoblastomycosis, possess a number of virulence factors that contribute to their pathogenicity. Among the most important virulence factors exhibited by dematiaceous fungi are:

- Melanin Production: Dematiaceous fungi generate the dark pigment melanin, which contributes to their virulence. Melanin provides protection against immune responses, such as phagocytosis and oxidative stress, that are generated by the host. It also aids in the formation of fungal cell walls, thereby increasing their resistance to antifungal agents.

- Adhesive Molecules: The adhesion of fungi to host tissues is a crucial stage in the establishment of an infection. On their cell surfaces, dematiaceous fungi produce molecules or structures that facilitate attachment to host cells and extracellular matrix components. This adhesive property facilitates the colonization and invasion of fungi.

- Extracellular Enzymes: Extracellular Enzymes Fungi of the genus Dematiaceae can secrete various extracellular enzymes that aid in tissue invasion and immune evasion. Proteases, lipases, and phospholipases are examples of these enzymes, which can degrade host tissues and interfere with the host’s immune system.

- Biofilm Formation: Some dematiaceous fungi are capable of forming biofilms, which are structured communities of fungal cells surrounded by a matrix of extracellular substances. Biofilms enhance fungal persistence and antifungal agent resistance. They can also promote the development of chronic infections and shield fungi from the immune defenses of the host.

- Resistance to Oxidative Stress: Resistance to Oxidative Stress Dematiaceous fungi have mechanisms to combat oxidative stress, a crucial host defense mechanism. They contain antioxidant enzymes and molecules that assist in neutralizing reactive oxygen species produced by the host’s immune cells.

- Immune Modulation: Dematiaceous fungi are able to modulate the immune response of their hosts to ensure their survival and persistence. They are able to manipulate immune cell signaling, cytokine production, and immune cell functions, enabling them to evade immune recognition and circumvent immune clearance.

- Formation of Sclerotic Bodies: Sclerotic bodies, also referred to as chromoblasts, are specialized structures formed by certain dematiaceous fungi within host tissues. These structures are immune clearance resistant and can persist for extended periods. They contribute to the recurrent nature of fungal infections, such as chromoblastomycosis.

Clinical Features of Chromoblastomycosis (Chromomycosis)

Chromoblastomycosis, also known as chromomycosis, is a chronic fungal infection of the epidermis and subcutaneous tissues. The clinical manifestations of chromoblastomycosis can vary depending on several variables, such as the causative fungus, the duration of infection, and the immune system of the host. Here are the typical clinical manifestations of chromoblastomycosis:

- Cutaneous Lesions: Cutaneous lesions are characteristic of chromoblastomycosis. Typically, these lesions form at the site of traumatic inoculation, such as the lower extremities, feet, or hands. They begin as papules or nodules and progress progressively over time. The lesions may appear elevated, plaque-like, or verrucous (wart-like).

- Nodular and Tumorous Lesions: As the infection progresses, cutaneous lesions may become nodular or malignant. These larger lesions may have irregular borders, a cauliflower-like appearance, and brown to black hues. Single or multiple nodules that can coalesce into larger plaques.

- Crusting and Ulceration: As lesions progress, a dense, crusted surface may form. The color of the crusts can be black, brown, or yellowish. Ulceration may develop over time, resulting in the formation of superficial or deep ulcers within the lesions. These sores are susceptible to secondary bacterial infections.

- Sclerotic Bodies (Chromoblasts): Sclerotic bodies, also referred to as chromoblasts, are recognizable structures within chromoblastomycosis lesions. These structures represent fungal cell aggregates and can be observed under a microscope. Their dark, pigmented appearance and distinct morphology distinguish them.

- Involvement of the Lymphatic System: In certain instances, chromoblastomycosis can extend to the regional lymph nodes. Involvement of the lymphatic system may result in lymphedema, lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes), and the formation of sinuses or fistulas.

- Localized Pruritus: Itching (pruritus) is a frequent sign of chromoblastomycosis. It can range from moderate to severe and has a significant impact on the quality of life of those affected.

- Secondary Complications: Chronic, long-lasting chromoblastomycosis can result in a variety of secondary complications. These complications include bacterial superinfections of the skin lesions, cellulitis (inflammation of the skin and subcutaneous tissues), and, in extremely uncommon instances, the development of squamous cell carcinoma in long-standing cases.

Diagnosis of Chromoblastomycosis (Chromomycosis)

Chromomycosis (chromoblastomycosis) is diagnosed using a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory investigations, and histopathology. The following diagnostic methods are commonly employed:

- Clinical Evaluation: A comprehensive clinical evaluation is the initial stage in diagnosing chromoblastomycosis. The dermatologist or infectious disease specialist will examine the skin lesions, evaluate their characteristics (appearance, color, and texture), and take the patient’s medical history and risk factors into account.

- Direct Microscopic Examination: The diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis requires a direct microscopic examination of skin scrapings or biopsies. Typically, the collected samples are stained with special stains for fungi, such as potassium hydroxide (KOH) or calcofluor white. This staining makes fungal elements, such as sclerotic bodies (chromoblasts), more visible within the tissue. The presence of pigmented fungal cells indicative of chromoblastomycosis is suggestive of the disease.

- Cultures of Fungi: Cultures of fungi are performed to isolate and identify the causal fungi. The gathered samples, such as skin scrapings or biopsies, are inoculated onto fungi-specific culture media, such as Sabouraud agar or potato dextrose agar. To permit fungal growth, cultures are incubated at appropriate temperatures (typically 25-30°C) for several weeks. Dematiaceous fungi, which commonly cause chromoblastomycosis, typically produce colonies with a dark pigmentation. Using morphological characteristics and additional laboratory tests, such as DNA sequencing or biochemical assays, the isolated fungus can be identified.

- Examen histopathologique: A histopathological examination of skin biopsies is frequently performed to evaluate the tissue changes associated with chromoblastomycosis. The biopsies are processed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with H&E or PAS stains. This examination identifies the presence of granulomas, chronic inflammation, and pigmented fungal cells (chromoblasts) in tissue.

- Molecular Techniques: In some instances, molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be utilized to aid in the identification of the causal fungus. PCR amplifies specific DNA sequences from fungi, allowing for a more rapid and accurate identification of species.

Treatment of Chromoblastomycosis (Chromomycosis)

The treatment of chromoblastomycosis (chromomycosis) aims to achieve complete clearance of the fungal infection and alleviate symptoms. The choice of treatment depends on several factors, including the specific causative fungus, the extent and severity of the infection, the patient’s overall health, and treatment availability. Here are the commonly used treatment modalities for chromoblastomycosis:

- Antifungal Medications:

- a. Oral Antifungals: Systemic antifungal medications are often the mainstay of treatment for chromoblastomycosis. The most commonly used oral antifungal agents include itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole. Treatment is typically long-term, ranging from months to years, and requires close monitoring of liver function and potential drug interactions.

- b. Topical Antifungals: In some cases, topical antifungal medications, such as ciclopirox olamine or amphotericin B, may be used in combination with systemic therapy to target localized lesions.

- Physical Modalities:

- a. Surgical Excision: Surgical removal of lesions can be considered in selected cases, particularly for single or localized lesions. This may be followed by antifungal therapy to prevent recurrence.

- b. Cryotherapy: The application of extreme cold (liquid nitrogen) to the lesions can be used as an adjunctive treatment. Cryotherapy helps destroy the fungal cells and stimulate the host immune response.

- Heat Therapy:

- a. Thermotherapy: Localized heat therapy, such as hyperthermia or radiofrequency, can be used as an alternative treatment option. It involves the application of high temperatures to the lesions to kill the fungal cells.

- Combination Therapy:

- a. Antifungal Combinations: In difficult-to-treat or refractory cases, combination therapy with multiple antifungal agents may be considered. This approach aims to improve treatment efficacy by targeting different aspects of the fungal infection.

Antifungal Resistance of causative agents of chromoblastomycosis

Antifungal resistance has been reported in chromoblastomycosis-causing fungi, such as Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Cladophialophora carrionii, Phialophora verrucosa, and other dematiaceous fungi, although it is relatively uncommon in comparison to other fungal infections. The susceptibility of these fungi to antifungal agents can vary, and resistance can develop as a result of a variety of factors, including intrinsic and acquired mechanisms. Here is an overview of antifungal resistance in fungi that cause chromoblastomycosis:

- Intrinsic Resistance: Some dematiaceous fungi, such as certain species of Fonsecaea and Cladophialophora, manifest reduced susceptibility to specific antifungal agents by nature. Compared to other fungal species, these fungi are typically less susceptible to azole antifungals, such as fluconazole.

- Resistance Acquired: Fungi that cause chromoblastomycosis have the potential to develop acquired resistance to antifungal drugs, particularly after prolonged or repeated exposure to these agents. Several factors, including suboptimal drug concentrations, inadequate treatment duration, and noncompliance with therapy, can influence the emergence of resistance.

- Azole Resistance: Resistance to Azole Antifungals: Azole antifungals, such as itraconazole and voriconazole, are frequently used to treat chromoblastomycosis. However, azole resistance has been documented in chromoblastomycosis-causing fungi in a few reports. Resistance mechanisms may include, among others, modifications to the target enzyme (14-alpha demethylase) or an increase in drug efflux.

- Multidrug Resistance: In some instances, chromoblastomycosis-causing fungi may develop resistance to multiple classes of antifungal agents, thereby restricting treatment options. This may necessitate alternative therapeutic strategies, such as combination therapy or surgical interventions, to manage the infection.

Prevention and Control of chromoblastomycosis

Prevention and control measures for chromoblastomycosis focus on minimizing exposure to the causative fungi and promoting good hygiene practices. While complete prevention may not be possible in certain environments, implementing the following measures can help reduce the risk of chromoblastomycosis:

- Personal Protective Measures:

- When working or engaging in activities that may involve contact with soil or vegetation, wear protective clothing, including long sleeves, long pants, and gloves.

- Use appropriate footwear, such as boots, to protect the feet from accidental injury and fungal exposure.

- Take precautions to avoid cuts, abrasions, or puncture wounds while working outdoors or in environments where fungal exposure is possible.

- Clean and disinfect gardening or farming tools after use, especially if they come into contact with soil or organic matter.

- Hygiene Practices:

- Maintain good personal hygiene, including regular handwashing with soap and water, particularly after working with soil or plants.

- Avoid prolonged contact with moist environments, such as wet soil or stagnant water, which may harbor fungal organisms.

- Keep the skin clean and dry, as excessive moisture can create a favorable environment for fungal growth.

- Properly dry and ventilate shoes and other footwear to prevent fungal colonization.

- Environmental Measures:

- Minimize exposure to decaying organic matter, as it may serve as a potential source of fungal spores. Avoid activities involving contact with decomposing vegetation or wood.

- Ensure proper sanitation and waste management practices to prevent the accumulation of organic matter that can harbor fungi.

- Occupational Safety:

- Workers involved in agriculture, forestry, horticulture, or other activities with potential fungal exposure should receive appropriate training on preventive measures, including the use of personal protective equipment.

- Employers should provide a safe working environment, including regular maintenance and cleaning of work areas to minimize fungal contamination.

- Early Diagnosis and Treatment:

- Promptly seek medical attention if you develop skin lesions or suspicious skin changes, especially if you have a history of occupational or recreational exposure to soil or plants.

- Early diagnosis and treatment can help prevent the progression of chromoblastomycosis and reduce the risk of complications.

FAQ

What is chromoblastomycosis?

Chromoblastomycosis, also known as chromomycosis, is a chronic fungal infection that affects the skin and subcutaneous tissues. It is caused by certain pigmented fungi, primarily from the dematiaceous (dark-colored) group. The infection typically occurs following traumatic inoculation of the fungi into the skin.

How is chromoblastomycosis transmitted?

Chromoblastomycosis is not directly transmitted from person to person. The primary mode of transmission is through traumatic implantation of fungal spores or hyphae into the skin, usually by contact with contaminated soil, decaying vegetation, or plant material. Occupational or recreational activities that involve exposure to these environmental sources increase the risk of infection.

What are the common symptoms of chromoblastomycosis?

The common symptoms of chromoblastomycosis include the development of skin lesions that gradually enlarge and become raised, verrucous, or nodular over time. The lesions often have a warty or cauliflower-like appearance and may be hyperpigmented. They can be accompanied by itching, pain, and occasional discharge of pus or other materials.

How is chromoblastomycosis diagnosed?

Chromoblastomycosis is diagnosed through a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and mycological examination. A skin biopsy is typically performed, and the tissue samples are examined under a microscope to identify characteristic fungal structures called sclerotic bodies or muriform cells. Fungal culture and molecular methods may also be employed to identify the specific causative fungi.

What are the causative agents of chromoblastomycosis?

The causative agents of chromoblastomycosis are various pigmented fungi belonging to genera such as Fonsecaea, Cladophialophora, Phialophora, Exophiala, and Rhinocladiella. Examples of species commonly associated with the infection include Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Cladophialophora carrionii, and Phialophora verrucosa.

Is chromoblastomycosis a common infection?

Chromoblastomycosis is considered a relatively rare fungal infection. It is more prevalent in certain geographic regions with warm and humid climates, such as tropical and subtropical areas. The exact prevalence of the infection worldwide is not well-established due to underreporting and regional variations in the disease’s occurrence.

What are the risk factors for developing chromoblastomycosis?

The main risk factors for developing chromoblastomycosis include:

Occupational or recreational activities involving contact with soil, plants, or decaying vegetation.

Traumatic injuries to the skin, such as cuts, punctures, or abrasions, that facilitate fungal entry.

Living in or traveling to endemic regions.

Weakened immune system, such as in individuals with HIV/AIDS or those receiving immunosuppressive therapy.

Can chromoblastomycosis be cured?

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic infection that can be challenging to cure completely. However, with appropriate and prolonged treatment, it is possible to control the infection and achieve remission. Treatment aims to eliminate the fungal infection, alleviate symptoms, and prevent complications or relapses. Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment improve the chances of successful management.

What is the treatment for chromoblastomycosis?

The treatment of chromoblastomycosis typically involves a combination of antifungal medications and physical interventions. Oral antifungal agents, such as itraconazole or terbinafine, are commonly used. In some cases, surgical excision or physical methods like cryotherapy or heat therapy may be employed to remove or destroy the infected tissue. Treatment duration can be prolonged, often ranging from months to years, depending on the extent and response to therapy.

How can chromoblastomycosis be prevented?

Prevention of chromoblastomycosis focuses on minimizing exposure to the causative fungi. Measures to reduce the risk include:

Wearing protective clothing, such as long sleeves, long pants, and gloves, when working with soil, plants, or decaying vegetation.

Avoiding direct contact with contaminated soil or organic matter.

Practicing good personal hygiene, including regular handwashing after outdoor activities.

Keeping skin clean and dry, as excessive moisture can promote fungal growth.

Educating individuals at higher risk, such as agricultural or forestry workers, about preventive measures and the importance of seeking medical attention for suspicious skin lesions.

References

- Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci DR, et al. Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(11):e367-e377. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30306-5

- Revankar SG, Sutton DA. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):884-928. doi:10.1128/CMR.00019-10

- Bonifaz A, Carrasco-Gerard E, Saúl A. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycologic experience of 51 cases. Mycoses. 2001;44(1-2):1-7. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0507.2001.00610.x

- Brandt ME, Warnock DW. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and therapy of infections caused by dematiaceous fungi. J Chemother. 2003;15 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):36-47. doi:10.1080/1120009X.2003.11750311

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(4):467-476. doi:10.1086/338599

- Silva MB, Costa JM, Castro LG, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: a retrospective study of 325 cases on Amazonic Region (Brazil). Mycopathologia. 2002;156(4):303-307. doi:10.1023/A:1020978300826

- Zhang H, Ran YP, Cao C, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: a clinical and microbiological study of 51 cases from mainland China. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):e36-e40. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03406.x

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D, Tirado-Sánchez A, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycological experience of 51 cases. Mycopathologia. 2008;165(6):287-294. doi:10.1007/s11046-007-9079-1

- Pérez-Blanco M, Ortoneda M, Capilla J, et al. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of five species of Fonsecaea causing chromoblastomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(7):1952-1954. doi:10.1128/aac.46.7.1952-1954.2002

- Liang Y, Wang H, Liu W, et al. Molecular identification of Fonsecaea causing human chromoblastomycosis in southern China. Mycopathologia. 2011;172(5):387-393. doi:10.1007/s11046-011-9473-6

Related Posts

- Basidiomycetes – Life cycle, Characteristics, Significance, Mycelium and Examples

- Deuteromycetes – Reproduction, Characteristics, Classification and Examples

- Yeast – Structure, Reproduction, Life Cycle and Uses

- Candida albicans – Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenesis, Treatment

- Hyphae – Definition, Types, Structure, Production, Functions, Examples