Contents

What is climax community?

- In the field of ecology, a climax community or climatic climax community is an old term for a group of plants, animals, and fungi that have reached a steady state through the process of ecological succession in the growth of vegetation in an area over time.

- It was believed that this equilibrium occurs because the climax community is comprised of species that are best adapted to the average conditions in that region.

- The term is also sometimes used in the process of making soil.

- Still, it has been found that a “steady state” is more of an illusion than a reality, especially over long periods of time. Despite that, it is still a useful idea.

- In the early 1900s, Frederic Clements came up with the idea of a single climax, which is defined by the climate of the area.

- Henry Cowles wrote in 1899 that succession leads to something like a climax, but it was Clements who used the word “climax” to describe succession’s ideal endpoint.

Climax community means

- The stable result of successional sequence, or sere, is the climax community.

- It is a group of organisms that live together and have reached a steady state in terms of species composition, structure, and energy flow.

- Steady state shows that the climax is very active.

- Also, the end of successional change doesn’t mean the end of community growth.

- As has been said, the climax community is always changing because people are born, die, and grow. This means that the structure of the community is also always changing.

- But these changes aren’t as big as the changes in communities that happen during succession.

Characteristics of a climax community

- The climax community can deal with how it acts.

- It tends to be mesic, which means it has a medium amount of water, instead of xeric (dry) or hydric (wet).

- The people who live in climax are better organised.

- With its more complicated organisation, the climax community has a large number of species and more places for them to live.

- Early stages of succession tend to have organisms that are smaller, don’t live as long, and have a higher biotic potential (r-selected). The species in the climax community, on the other hand, tend to be big, live a long time, and have a low biotic potential (K-selected).

- In a climax community, energy is stable (net primary production is zero), but in an immature stage of succession, gross primary production is usually higher than community respiration, which means that energy is being stored.

- Young ecosystems aren’t very stable, but climax communities are very stable.

- Climax communities change less and are more resistant to invasions than ecosystems that are still young.

Nature of Climax Community

1. Poly-climax and Mono-climax

- Clements (1916) said that succession led to a single true climax community, which was mostly determined by the climate of the area.

- This way of thinking is called the “mono-climax theory of succession,” and it says that all of the different kinds of plant communities in a region are just different stages of the real “climax” community.

- People used the terms “subclimax,” “pre-climax,” and “post-climax” to describe these different types of plant communities.

- This theory also says that, given enough time, the differences in soil moisture, temperature, availability of nutrients, hydrology, and other factors that lead to different types of vegetation would be evened out and a uniform true climax would form.

- Many observations seem to go against this theory, as it is clear that it was hard to find large areas of uniform vegetation even in the past. Instead, it’s better to recognise more than one community as the climax.

- The poly-climax theory of succession says that, depending on local conditions, the climax community is made up of many different kinds of plants.

- The whole environment, not just the climate, should be in harmony with the climax community. But the idea of poly-climax is mostly just a matter of terminology.

2. Pattern theory of Climax

- Robert H. Whittaker came up with a third theory called “climax pattern theory” in 1953. This theory disagrees with the classification approach.

- It recognises that there is a regional pattern of open climax communities, the make-up of which depends on the local environmental conditions at any given time.

- In a way, the climax pattern concept looks at only one large community that changes based on soil, slope, and other habitat factors.

- This method is thought to be better and more realistic for describing this pattern of change.

Factors Affecting the Nature of Climax Community

- The type of climax community is determined by many things, such as the soil’s nutrients, moisture, slope, exposure, etc.

- Another important part of many climax communities is fire. Plants that can survive fires are given more space, while other plants that would have done better are taken out.

- In some pine species, fire makes the seeds fall off. After the fire is out, pine seedlings grow quickly because they don’t have any competition.

- Grazing pressure is another thing that affects what kind of community climax is. When grasslands are grazed a lot, they may turn into shrublands.

- Shrubs and cacti may take over because they are not good for food. Many herbivores may kill off a lot of plant species by eating them, making room for plants that aren’t as good for eating.

Transient and cyclic climax

- Once the climax community is set up, even though people are always coming and going, the overall look of the community doesn’t change. But not all climate peaks last forever.

- A climax community can’t stay stable for long because things like storms, fires, cold waves, changes in the seasons, etc., all have bad effects.

- Changes in the composition of a community’s plants and animals that don’t follow a successional pattern and last only a short time and can be reversed are also common. People say that these are examples of brief climax.

- Transient climaxes form around resources and habitats that don’t last long, like temporary ponds and dead animals.

- A simple example of a transient climax is the growth of animal and plant communities in seasonal ponds.

- The communities are always destroyed because the water in the ponds either dries up in the summer or freezes solid in the winter.

- Every year, during the growing season, these communities start up again from the pores and resting stages that plants, animals, and microorganisms leave behind.

- The waste and bodies of dead organisms are another example. They provide food and shelter for a wide range of trash eaters and scavengers.

- In African savannas, many vultures feed on the dead body of a large animal.

- First, the big, aggressive species eats the biggest chunks of meat. Then, the smaller, less aggressive species comes in and picks out smaller pieces of meat from the bones.

- Lastly, a different kind of vulture moves into the area. This one breaks the bones open and eats the bone marrow.

- Later, scavenger animals, maggots, and microorganisms move in and make sure nothing edible is left. When the feast is over, all of the scavengers go their separate ways.

- So, there is no climax in this kind of progression, unless we count all the scavengers as a climax.

- A cyclic climax could be caused by just a few dominant species in a few simple communities.

- There is a cyclic climax when each species can only survive with the help of another species.

- The life cycle of the dominant species is what causes the change in the cycle.

- Stable cyclic climaxes usually have a pattern that repeats itself, and one of the stages is often bare substrate. Cycles of climaxes are caused by harsh weather, such as frost, strong winds, etc.

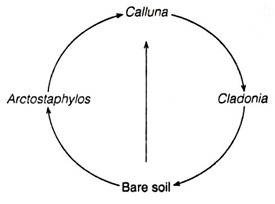

- Watt looked at examples of how plants change over time (1947). Watt found that the dwarf Calluna heath was the most common type of shrub in Scotland. As it gets older, it loses its strength and the lichen Cladonia starts to grow on it. When the lichen mat dies, the ground is left bare.

- Bearberry has taken over this empty space (Arctostaphylos). Calluna then comes in and takes over. Calluna is the most common plant, but Arctostaphylos and Cladonia are allowed to grow in the space it leaves behind.

- So, the cyclic sequence is set by the life history of this dominant plant:

- The idea of climax community includes both patterns of change that repeat and patterns of distribution that look like a mosaic.

- The climax is a dynamic state that keeps going on its own. The key to climax is to keep going. In a climax community, all species, including the dominant species, are able to keep reproducing and live in an area with the same climate.

Theories of the Climax Community

- The final stage of succession is called the climax or climax community (Clements, 1936; Shimwell 1971). (Clements, 1936; Shimwell 1971).

- It is the last or most stable of a series of communities. It keeps going on its own and is in balance with its physical and biological surroundings.

- Climax communities undergo changes in structure as a result of birth, death and growth processes in the community.

There are several ideas about what happens at the end:

1. Mono-climax Theory

- According to the mono-climax theory of succession (Clements, 1936), each region has a single climax community towards which all other communities evolve.

- He felt that climate was the determining factor for vegetation and that a region’s climax was purely dependent on its climate.

- Sub-climax, dis-climax, post-climax, and pre-climax are terminology used to characterise departures from the climatically stable climax.

- These communities, which are governed by topography, edaphic (soil), or biotic variables, are considered exceptions by proponents of the mono-climax theory.

2. Poly climax Theory

- Tansley (1939) proposed this idea, which Daubenmire subsequently supported (1966).

- According to the poly-climax theory of succession, it is possible to identify numerous varieties of climax vegetation in a particular area.

- These climaxes will be governed by soil moisture, soil nutrients, animal activity, and other variables.

- According to this view, climate is merely one of several elements that might exert control over the structure and stability of the climax.

- This allows for several climaxes in a climate region and is so known as the poly-climax theory.

- The primary distinction between this theory and the mono-climax hypothesis lies in the focus placed on the element responsible for the stability of a climax.

- According to Krebs (1994), the true distinction between two theories resides in the measurement of relative stability across time.

- The climate fluctuates on both an ecological and a geological time frame. Therefore, succession is in a sense continuous because changeable vegetation is approaching variable climate.

3. Climax-pattern Theory

- Whittaker (1953) emphasised that a natural community is adapted to the entire pattern of environmental factors in which it exists; the major factors are the genetic structure of each species, climate, site, soil, biotic factors (animal activity), fire, and wind, availability of plant and animal species, and dispersal chances.

- This hypothesis states that climax communities are patterns of populations that alter according to the whole environment.

- Thus, there is no discrete number of peak communities, and no one factor controls their shape and stability.

- In contrast to the mono-climax theory and the poly-climax theory, which allow for many climatic climaxes in a region, the climax-pattern hypothesis allows for a continuity of climax types that vary gradually over environmental gradients and are not clearly separable into discrete climax types.

4. Climax as Vegetation

- According to Egler (1954), “climaxes” in a wide sense are nothing more than the whole of vegetation. He therefore advocates the study of vegetation, as it is, with thorough observations to explain and understand the past, present, and future conditions of specific communities.

- From these views, we might deduce that the endpoint of succession is climax, which is inherently unstable.

- The climate of a place controls the vegetation in its whole; nevertheless, within each of the main climatic zones, soil, topography, and animals contribute to a variety of climax circumstances.

- Not always do climax communities indicate the end of successional transition.

Related Posts

- Ecological Succession – Definition, Types, Mechanism, Examples

- Detritus Food Chain – Definition, Energy Flow, Examples

- Grazing Food Chain – Definition, Types, Examples and Features

- Models of Energy Flow in a Ecosystem – Linear and Y-shaped food chains

- Biogeochemical Cycle – Definition, Importance, Examples