Growth at 42°C test is a physiological test used in microbiology for the identification and differentiation of certain non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria. It is the process where the organism is tested for its ability to grow and survive at a higher temperature of 42°C. This test is mainly applied for the differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from other closely related fluorescent pseudomonads. It is observed that P. aeruginosa shows growth at this elevated temperature while many other species fail to grow.

It is the important diagnostic feature of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as this organism is adapted to grow at 42°C although its optimum temperature is around 37°C. This thermotolerant nature is associated with its pathogenic nature in humans. In contrast, species such as Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida are environmental organisms and these are unable to grow at 42°C. Hence this test is referred to as a simple and reliable method for laboratory differentiation. The test is also useful in identification of Acinetobacter baumannii which is able to grow even at 44°C as compared to other species of Acinetobacter.

In this test a young colony of the test organism is inoculated into two tubes containing culture media such as Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) or Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB). One tube is incubated at 35°C to 37°C which acts as a control for normal growth. The second tube is incubated at 42°C. After an incubation period of 18 to 24 hours the tubes are examined for growth. Growth at both temperatures indicates a positive result whereas growth only at the control temperature indicates a negative result. TSA slants are generally preferred because heavy inoculum in broth may produce turbidity leading to false positive results.

Objectives of Growth at 42°C Test

- To differentiate Pseudomonas aeruginosa from other fluorescent pseudomonads which are unable to grow at 42°C.

- To distinguish Pseudomonas aeruginosa from species such as Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida on the basis of thermotolerance.

- To determine the ability of an organism to survive and grow at elevated temperature of 42°C.

- To use as a presumptive identification test for non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria.

- To aid in identification of Acinetobacter baumannii which shows growth at higher temperature as compared to other Acinetobacter species.

- To help in differentiating Stenotrophomonas maltophilia which generally shows negative growth at 42°C.

Principle of Growth at 42°C Test

The principle of Growth at 42°C test is based on the physiological ability of certain bacteria to grow and survive at higher temperature conditions. It is the process where organisms are tested for their capacity to tolerate and multiply at 42°C which depends upon enzymatic stability and metabolic adaptation of the organism. This principle is mainly applied for the differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from other fluorescent pseudomonads.

It is observed that Pseudomonas aeruginosa has an optimum growth temperature of 37°C but it is capable of growing at 42°C due to its thermotolerant nature. In contrast, related species such as Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida are unable to withstand this elevated temperature and hence fail to grow. In this test the organism is inoculated on suitable medium like Trypticase Soy Agar or broth and incubated at 42°C. The appearance of growth indicates a positive result while absence of growth indicates a negative result and helps in presumptive identification of the organism.

Requirements for Growth at 42°C Test

- Culture media – Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA) slants or Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) is used for the test. Agar slants are mostly preferred to avoid false positive results caused by heavy turbidity in broth.

- Sterile inoculating tools – Sterile inoculating loop or needle is required for transfer of the organism.

- Incubator – Two incubators are required one maintained at 35°C–37°C and the other maintained at 42°C.

- Test organism – A fresh young culture of the organism to be tested is required.

- Positive control organism – A known strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa showing growth at 42°C.

- Negative control organism – A known strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens or Pseudomonas putida which does not grow at 42°C.

- Light inoculum – A light inoculum is essential to avoid false positive interpretation of growth.

- Incubation period – Incubation for 18–24 hours is required for observation of results.

Tryptic Soya Agar Composition

| Ingredients | Gms / Litre |

| Tryptone | 17.000 |

| Soya peptone | 3.000 |

| Sodium chloride | 5.000 |

| Dextrose (Glucose) | 2.500 |

| Dipotassium hydrogen phosphate | 2.500 |

| Agar | 15.000 |

| Final pH ( at 25°C) | 7.3±0.2 |

Tryptic Soya Agar Preparation

- Suspend 45 grammes of Tryptic Soya Agar powder in 1000 cc of pure or distilled water.

- Heat the medium and bring to boil for complete dissolution of the agar.

- Sterilise the medium by autoclaving at 121°C at 15 pounds pressure for 15 minutes.

- After autoclaving allow the medium to cool to about 45–50°C.

- Mix well and pour into sterilised Petri dishes and allow to solidify.

Procedure of Growth at 42°C Test

- Select a single isolated colony of the test organism which is 13–24 hours old.

- With the help of a sterile inoculating loop or needle take a light inoculum from the selected colony.

- Inoculate two separate tubes containing Tryptic Soya Agar slants or Trypticase Soy Broth.

- Incubate one inoculated tube at 35°C or 37°C which serves as control for viability of the organism.

- Incubate the second inoculated tube at 42°C immediately.

- Allow the tubes to incubate for 18–24 hours.

- Observe the tubes for growth in the form of colonies on agar slants or turbidity in broth.

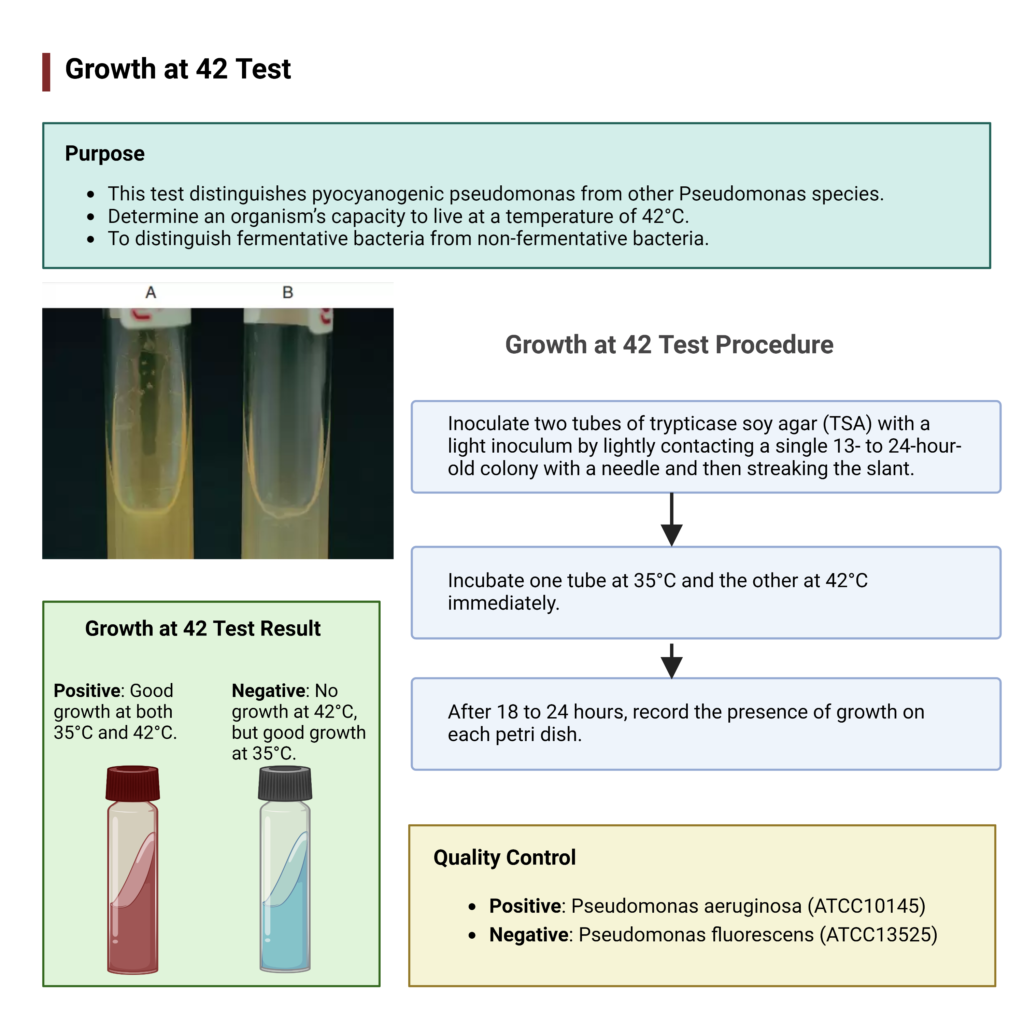

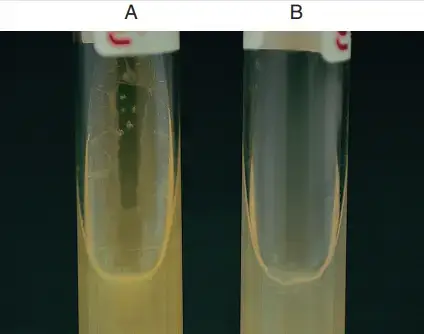

Result of Growth at 42°C Test

- Positive result (+)

- Growth is observed at both control temperature (35°C or 37°C) and at 42°C.

- It indicates that the organism is thermotolerant.

- The organism is most likely Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- Other organisms showing positive result include Acinetobacter baumannii and some strains of Achromobacter xylosoxidans and Pseudomonas stutzeri.

- Negative result (–)

- Growth is observed only at control temperature (35°C or 37°C) but no growth at 42°C.

- It indicates that the organism is not able to tolerate higher temperature.

- The organism is likely Pseudomonas fluorescens or Pseudomonas putida.

- Other organisms showing negative result include Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus.

- Note

- Slight turbidity may be seen in broth media due to heavy inoculum which may lead to false positive result.

- Agar slants are preferred for accurate interpretation.

Quality Control

- Positive: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC10145)

- Negative: Pseudomonas fluorescens (ATCC13525)

Uses of Growth at 42°C Test

- It is used for differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from other fluorescent pseudomonads.

- It helps in distinguishing Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida which do not grow at 42°C.

- It is useful in differentiation of pathogenic Acinetobacter baumannii from other species of Acinetobacter.

- It helps in identification of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia which shows negative growth at 42°C.

- It is used as a presumptive identification test for non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli based on their ability to tolerate higher temperature.

Precautions of Growth at 42°C Test

- A light inoculum should always be used to avoid false positive results due to heavy turbidity especially in broth media.

- Two sets of media must be inoculated simultaneously one for control incubation at 35°C–37°C and the other for test incubation at 42°C.

- Proper and accurate temperature should be maintained throughout the incubation period as slight variation in temperature may affect the result.

- Tryptic Soya Agar slants are preferred over broth media as broth may give false positive results.

- The inoculated tubes should be incubated immediately after inoculation to prevent temperature variation effects.

- Media should be properly prepared and sterilised before use and slants should be cooled in slanted position when required.

- Results should be interpreted carefully as strain variation may occur and this test should not be used as the only confirmatory test for identification.

Advantages of Growth at 42°C Test

- It is useful for differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from other fluorescent pseudomonads.

- It helps in distinguishing Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida which do not grow at 42°C.

- It aids in identification and differentiation of Acinetobacter baumannii from other non-pathogenic Acinetobacter species.

- It helps in differentiation of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia from thermotolerant non-fermentative bacteria.

- It gives an idea about pathogenic potential of the organism based on its ability to tolerate higher temperature.

- It is a simple, economical and reliable test which can be easily performed in routine microbiology laboratory.

Limitations of Growth at 42°C Test

- The result of the test depends on the type of media used and broth media may give false positive results due to turbidity.

- Variation may occur among different strains of the same species which may affect reliability of the test.

- A positive result is not specific only for Pseudomonas aeruginosa as other organisms may also grow at 42°C.

- Accurate temperature maintenance is required as slight fluctuation may alter the test result.

- Heavy inoculum may lead to false positive interpretation especially in broth media.

- This test is not a confirmatory test and should not be used alone for final identification.

- Interpretation of slight growth or turbidity may be subjective and may lead to error.

- Allan, B., Linseman, M., MacDonald, L. A., Lam, J. S., & Kropinski, A. M. (1988). Heat shock response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Bacteriology, 170(8), 3668–3674. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.170.8.3668-3674.1988

- Alsan, M., & Klompas, M. (2010). Acinetobacter baumannii: An emerging and important pathogen. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management, 17(8), 363–369.

- Araos, R., & D’Agata, E. (n.d.). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Pseudomonas species. In Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (Chapter 219). Repositorio UDD.

- Aryal, S. (2022, August 10). Growth at 42 test – Principle, procedure, uses and interpretation. Microbiology Info.com. https://microbiologyinfo.com/growth-at-42-test/

- Benamara, H., Rihouey, C., Abbes, I., Ben Mlouka, M. A., Hardouin, J., Jouenne, T., & Alexandre, S. (2014). Characterization of membrane lipidome changes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa during biofilm growth on glass wool. PLoS One, 9(9), e108478. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108478

- Bouffartigues, E., Si Hadj Mohand, I., Maillot, O., Tortuel, D., Omnes, J., David, A., Tahrioui, A., Duchesne, R., Azuama, C. O., Nusser, M., Brenner-Weiss, G., Bazire, A., Connil, N., Orange, N., Feuilloley, M. G. J., Lesouhaitier, O., Dufour, A., Cornelis, P., & Chevalier, S. (2020). The temperature-regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cmaX-cfrX-cmpX operon reveals an intriguing molecular network involving the sigma factors AlgU and SigX. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, 579495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.579495

- Bouvet, P. J. M., & Grimont, P. A. D. (1986). Taxonomy of the genus Acinetobacter with the recognition of Acinetobacter baumannii sp. nov., Acinetobacter haemolyticus sp. nov., Acinetobacter johnsonii sp. nov., and Acinetobacter junii sp. nov. and emended descriptions of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter lwoffii. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 36(2), 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-36-2-228

- Elfadadny, A., Ragab, R. F., AlHarbi, M., Badshah, F., Ibáñez-Arancibia, E., Farag, A., Hendawy, A. O., De los Ríos-Escalante, P. R., Aboubakr, M., Zakai, S. A., & Nageeb, W. M. (2024). Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Navigating clinical impacts, current resistance trends, and innovations in breaking therapies. Frontiers in Microbiology, 15, 1374466. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1374466

- Gautam, V., Kumar, S., Kaur, P., Deepak, T., Singhal, L., Tewari, R., & Ray, P. (2015). Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Burkholderia cepacia complex & Stenotrophomonas maltophilia from North India: Trend over a decade (2007-2016). Indian Journal of Medical Research, 152(6), 656–661. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_9_19

- Grosso-Becerra, M. V., Croda-García, G., Merino, E., Servín-González, L., Mojica-Espinosa, R., & Soberón-Chávez, G. (2014). Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors by two novel RNA thermometers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(43), 15562–15567. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1402536111

- Kahli, H., Béven, L., Grauby-Heywang, C., Debez, N., Gammoudi, I., Moroté, F., Sbartai, H., & Cohen-Bouhacina, T. (2022). Impact of growth conditions on Pseudomonas fluorescens morphology characterized by atomic force microscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(17), 9579. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23179579

- Krajewski, S. S., Nagel, M., & Narberhaus, F. (2013). Short ROSE-like RNA thermometers control IbpA synthesis in Pseudomonas species. PLoS One, 8(5), e65168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065168

- LaBauve, A. E., & Wargo, M. J. (2012). Growth and laboratory maintenance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Current Protocols in Microbiology, 06(1), Unit 6E.1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471729259.mc06e01s25

- Lee, S. A., & Jonas, R. M. (n.d.). Genomic evolution in Pseudomonas fluorescens as a result of gradual temperature changes. Fine Focus.

- Lister, P. D., Wolter, D. J., & Hanson, N. D. (2009). Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 22(4), 582–610. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00040-09

- Ma, Q., Zhai, Y., Schneider, J. C., Ramseier, T. M., & Saier Jr, M. H. (2003). Protein secretion systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and P. fluorescens. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Biomembranes, 1611(1-2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00059-2

- Malik, A. F. (2016, February 4). For all member, What is differences of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and how to identify both? ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/post/for-all-member-What-is-differences-of-pseudomonas-fluorescens-and-pseudomonas-aeruginosa-and-how-to-identify-both

- Manaia, C. M., & Moore, E. R. B. (2002). Pseudomonas thermotolerans sp. nov., a thermotolerant species of the genus Pseudomonas sensu stricto. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 52(6), 2203–2209. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.02059-0

- Microbiology In Pictures. (n.d.). Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. https://www.microbiologyinpictures.com/stenotrophomonas-maltophilia.html

- Moreno, R., & Rojo, F. (2014). Features of pseudomonads growing at low temperatures: Another facet of their versatility. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 6(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12150

- Mozaheb, N., Van Der Smissen, P., Opsomer, T., Mignolet, E., Terrasi, R., Paquot, A., Larondelle, Y., Dehaen, W., Muccioli, G. G., & Mingeot-Leclercq, M.-P. (2022). Contribution of membrane vesicle to reprogramming of bacterial membrane fluidity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mSphere, 7(3), e00187-22. https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00187-22

- Murugaiyan, J., Palpandi, K., Das, V., & Anand Kumar, P. (2024). Rapid species differentiation and typing of Acinetobacter baumannii. German Journal of Veterinary Research, 4(3), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.51585/gjvr.2024.3.0096

- Oberhofer, T. R. (1979). Growth of nonfermentative bacteria at 42°C. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 10(6), 800–804. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.10.6.800-804.1979

- Rajkumari, N., Mathur, P., Gupta, A. K., Sharma, K., & Misra, M. C. (2015). Epidemiology and outcomes of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Burkholderia cepacia infections among trauma patients of India: A five year experience. Journal of Infection Prevention, 16(3), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757177414558437

- Robinson, R. E., Robertson, J. K., Prezioso, S. M., & Goldberg, J. B. (2025). Temperature controls LasR regulation of piv expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio, 16(6), e00541-25. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00541-25

- Serretiello, E., De Prisco, M., Di Siervi, G., Cosimato, I., Dell’Annunziata, F., Santoro, E., Vozzella, E. A., Boccia, G., Folliero, V., & Franci, G. (2025). A nine-year review of Acinetobacter baumannii infections frequency and antimicrobial resistance in a single-center study in Salerno, Italy. Pathogens, 14(11), 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111165

- Silverio, M. P., Kraychete, G. B., Rosado, A. S., & Bonelli, R. R. (2022). Pseudomonas fluorescens complex and its intrinsic, adaptive, and acquired antimicrobial resistance mechanisms in pristine and human-impacted sites. Antibiotics, 11(8), 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11080985

- Silverio, M. P., Schultz, J., Parise, M. T. D., Parise, D., Viana, M. V. C., Nogueira, W., Ramos, R. T. J., Góes-Neto, A., Azevedo, V. A. D. C., Brenig, B., Bonelli, R. R., & Rosado, A. S. (2025). Genomic and phenotypic insight into antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas fluorescens from King George Island, Antarctica. Frontiers in Microbiology, 16, 1535420. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1535420

- Surendra Gopal, K. (2019, November 28). How to differentiate Pseudomonas fluoresence and Pseudomonas aeruginosa? ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/post/How-to-differentiate-Pseudomonas-fluoresence-and-Pseudomonas-aeruginosa

- Systematic evaluation of thermal tolerance as a phenotypic marker for non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli: The growth at 42°C test in clinical and environmental microbiology. (n.d.). [Report provided in source text].

- Vijayakumar, S., Biswas, I., & Veeraraghavan, B. (2019). Accurate identification of clinically important Acinetobacter spp.: An update. Future Science OA, 5(6), FSO395. https://doi.org/10.2144/fsoa-2018-0127

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Pseudomonas fluorescens. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudomonas_fluorescens

- Zeng, B., Wang, C., Zhang, P., Guo, Z., Chen, L., & Duan, K. (2020). Heat shock protein DnaJ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa affects biofilm formation via pyocyanin production. Microorganisms, 8(3), 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8030395