Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- Infection with human papillomavirus (HPV infection) is caused by a Papillomaviridae DNA virus. Most HPV infections are asymptomatic, and 90% of them resolve on their own within two years.

- In some instances, a persistent HPV infection develops in either warts or precancerous lesions. Depending on the affected site, these lesions raise the chance of cervix, vulva, Genital passage, penis, anus, mouth, tonsils, or throat cancer.

- Two strains of HPV, HPV16 and HPV18, account for around 70% of cervical cancer cases. Almost 90% of HPV-positive oropharyngeal malignancies are caused by HPV16. HPV is connected to between 60 and 90 percent of the various malignancies listed above. Common causes of genital warts and laryngeal papillomatosis are HPV6 and HPV11.

- Human papillomavirus, a DNA virus from the papillomavirus family, causes an HPV infection. Around 170 kinds have been described.

- Several types of HPV can infect a single individual,[9] and the disease is known to afflict exclusively humans. More than forty forms of herpes can be transmitted by sexual contact and infect the anus and genitals.

- Early age of first sexual encounter, frequent sexual partners, smoking, and impaired immune function are risk factors for persistent infection by sexually transmitted diseases.

- These varieties are primarily transmitted by prolonged skin-to-skin contact, with Genital passageand Rectal intercourse being the most common routes.

- During pregnancy, HPV infection can potentially transfer from mother to child. There is no evidence that HPV may spread through everyday items like toilet seats; nevertheless, HPV strains that produce warts may spread through surfaces like floors.

- Hand sanitizers and disinfectants are ineffective against HPV, which increases the likelihood of the virus being transmitted via nonliving infectious agents known as fomites.

Structure of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

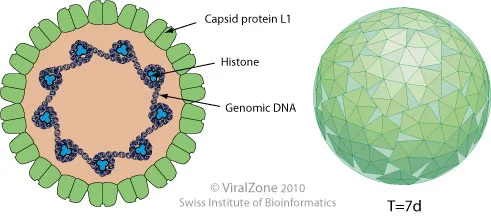

- HPV is a small non-enveloped virus with a double-stranded closed circular DNA genome.

- It is associated with histone-like proteins and protected by a capsid formed by two late proteins, L1 and L2.

- The capsid is composed of 72 capsomeres, each of which is composed of five monomeric units that join to form a pentamer corresponding to the major protein capsid, L1.

- The L1 pentamers are distributed forming a network of intra- and interpentameric disulfide interactions which serve to stabilize the capsid.

- The minor capsid proteins, L2 protein, with approximately 75kDa exist within the virion.

- To assemble the viral capsid, the pentamers join to copies of L2 that occludes the center of each pentavalent capsomere.

- Each virion contains 72 copies of L1 and a variable number of copies of L2, forming a particle with icosahedra symmetry and approximately 50 to 60 nm in diameter.

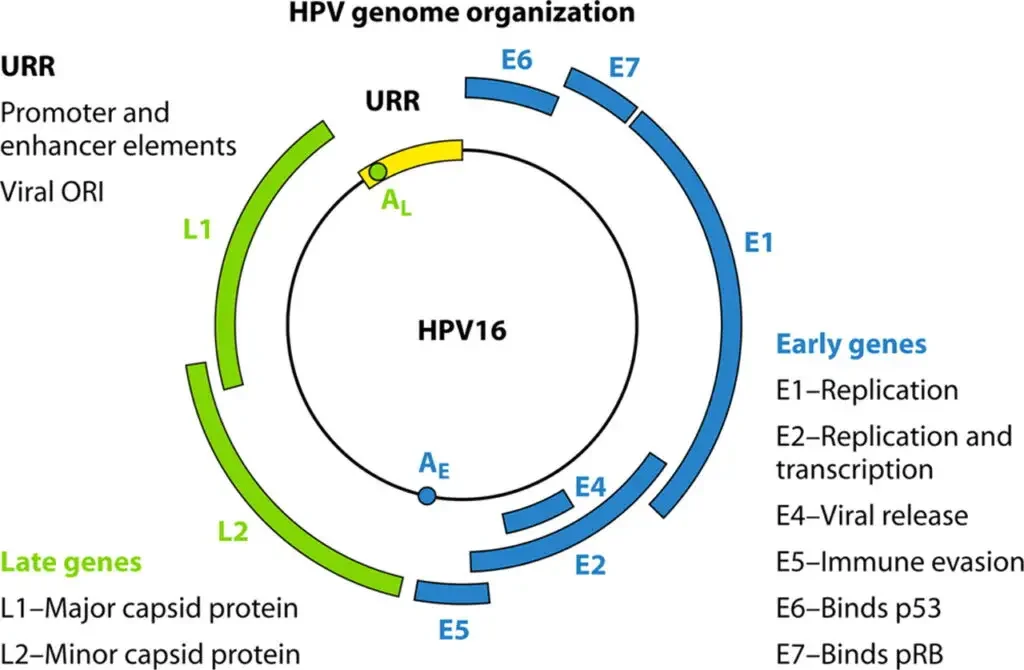

Genome Structure of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- The HPV genome is a circular, double-stranded DNA molecule containing about 8000 base pairs and around 8 open reading frames (ORFs).

- The HPV genome is divided into three regions: a noncoding upstream regulatory region (URR) or long control region (LCR), an early region (E) with six ORFs that encode non-structural proteins involved in viral replication and oncogenesis, and a late (L) region that encodes the L1 and L2 structural proteins.

- The LCR region ranges in size between 800-900 pb and represents about 10% of the genome. It varies substantially in nucleotide composition between individual HPV types.

- Only one strand of the double-stranded DNA is used as the template for viral gene expression, coding for a number of polycistronic mRNA transcripts.

- Viral gene expression is complex and controlled by cellular and viral transcription factors. Most of the regulation occurs within the LCR region, which contains cis-active element transcription regulators.

- The transcription start sites of viral promoters differ depending on the virus type, but promoter usage is keratinocyte differentiation-dependent.

- The replication origin and many transcriptional regulatory elements are found in the upstream LCR region. The virus early promoter, differentiation-dependent late promoter, and two polyadenylation signals define three general groups of viral genes that are coordinately regulated during host cell differentiation.

- The E6 and E7 genes maintain replication competence. E1 E2, E4, E5, and E8 are involved in virus DNA replication, transcriptional control, beyond other late functions, and L1 and L2, responsible for the assembly of viral particles.

- The regulation of expression of the late genes in genital HPVs is not well understood. However, it has been shown that the second, or later, promoter is initiated in a differentiation-dependent manner and is activated only when cells are grown in the host’s stratifying/differentiating tissue.

- Activation of the later promoter is accompanied by acceleration of viral DNA replication and high levels of viral protein expression. As a result, virus copy-number amplifies from 50 copies to several thousands of copies per cell.

- When the later promoter is activated, the expression of genes encoding the structural proteins L1 and L2 occurs, which join to assemble the capsids and to form virions.

Functions of viral proteins

| Protein | Function |

|---|---|

| E1 | Viral DNA replication |

| E2 | Control of viral transcription, DNA replication, and segregation of viral genomes |

| E4 | Favor and support the HPV genome amplification; regulate the expression of late genes; control virus maturation; facilitate the release of virions |

| E5 | Enhance the transforming activity of E6 and E7; promote fusion between cells, generating aneuploidy and chromosomal instability; contribute to immune response evasion |

| E6 | Bind and degrade the tumor-suppressor protein p53, inhibiting apoptosis; interact with proteins of the innate immune response, contributing to immune evasion and persistence of the virus; activate the expression of telomerase |

| E7 | Bind and degrade the tumor-suppressor protein pRB; increase cdk activity; affect the expression of S phase genes by directly interacting with E2F factors and with histone deacetylases; induce a peripheral tolerance in cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and downregulate the expression of TLR9, contributing to immune response evasion |

| L1 | Major capsid protein; contains the major determinant required for attachment to cell surface receptors; highly immunogenic and has conformational epitopes that induce the production of neutralizing type-specific antibodies against the virus |

| L2 | Minor capsid protein; contributes to the binding of virion in the cell receptor, favoring its uptake, transport to the nucleus, and delivery of viral DNA to replication centers; helps the packaging of viral DNA into capsids, along with E2 |

Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

There are more than 180 different subtypes of HPV that have been identified. Some subtypes, including 1, 2, 4, 27, and 57, are known to cause cutaneous warts on the hands and feet, which are spread through skin-to-skin contact or contact with infected objects. Subtypes 6 and 11 are classified as low-risk HPV and are usually responsible for anogenital warts, as well as juvenile and adult recurrent respiratory papillomatosis.

On the other hand, subtypes 16 and 18 are considered high-risk HPV, and are the most common culprits for causing precancerous and cancerous lesions in the cervix, anogenital areas in both males and females, and the oropharyngeal area. Additionally, subtypes 31, 33, 35, 45, 52, and 58 are also classified as high-risk HPV and are associated with the development of cervical cancer.

It’s important to note that although sexual contact is the primary mode of transmission for both low-risk and high-risk HPV, close contact can also transmit the virus. Recent studies by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that the prevalence of HPV in adults aged 18 to 59 is around 45.2% in men and 39.9% in women. Genital HPV infection is currently the most common sexually transmitted infection both in the United States and worldwide.

Transmission of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) is primarily transmitted through skin-to-skin contact, typically during sexual activity.

- However, HPV can also be transmitted through other forms of close contact, such as touching an infected area or sharing towels or other personal items with an infected person.

- HPV can be spread even if the infected person shows no visible signs or symptoms of the infection. It is important to practice safe sex and get vaccinated against HPV to reduce the risk of transmission and development of associated health problems.

Replication of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)/Replicative Cycle of HPVs

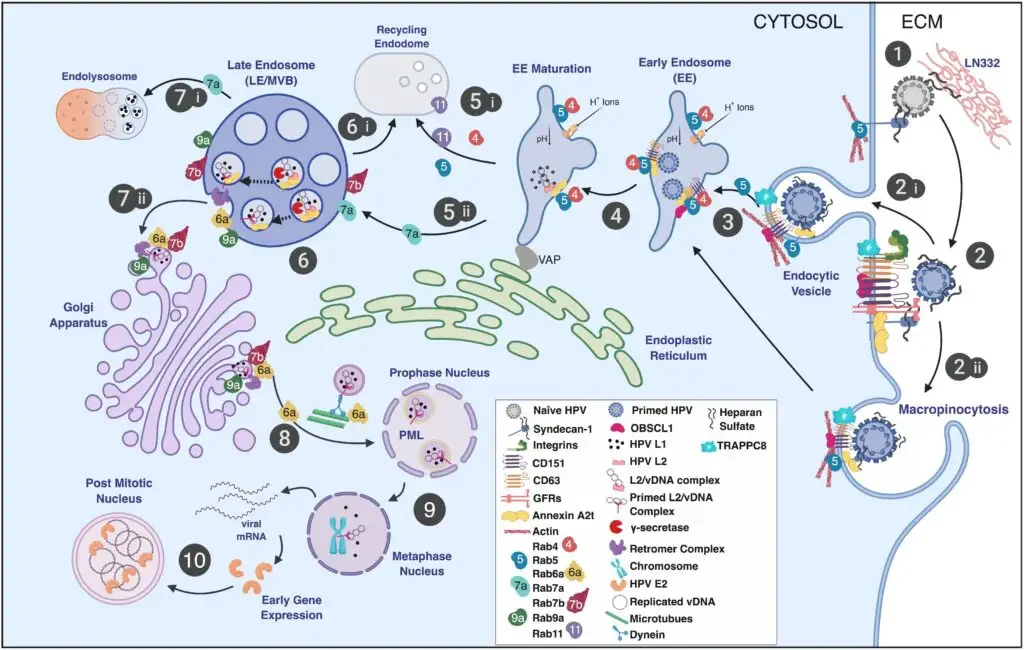

Schematic illustration of the HPV infectious entrance pathway in keratinocytes, highlighting the role of Rab-GTPases in HPV trafficking.

- Step 1: HPV virions bind the extracellular matrix (ECM), basement membrane, and/or plasma membrane by means of HSPGs (such as syndecan-1) and laminin-332 (LN332).

- Step 2: Attached virions are conformationally modified by host enzymes, liberated from the plasma membrane or extracellular matrix (ECM), and translocated to tetraspanin-enriched microdomains harboring a putative uptake receptor complex (e.g., CD151, CD63, integrins, A2t, EGFR, etc.). It is believed that viral uptake occurs by (step 2i) receptor-mediated endocytosis and (step 2ii) a process akin to macropinocytosis, which is classified as clathrin-, caveolin-, dynamin-, cholesterol-, flotillin-, and lipid raft-independent.

- Step 3: Entry is assisted by actin polymerization and remodeling involving CD151, CD63, adaptor proteins (such as OBSCL1 and syntenin-1), A2t, and TRAPPC8, resulting in virion localization to EE.

- Step 4: It is believed that viral localization to EE is dependent on CD63 and Rab5 and is connected to the acidity of EE.

- Step 5: Endosomal tubulation is then initiated by the development of an ER interaction through the VAP complex. The acidity of EE dissociates the viral capsid, releasing the viral genome in combination with L2. EE can develop into either recycling endosomes (step 5i) or LE/MVB (step 5ii). Rab conversion is linked to endosomal maturation and defines Rab function (step 5i,5ii; see the text for details).

- Step 6: γ-secretase cleaves intraluminal L2 to expose the L2 cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) and a transmembrane domain. Recycling endosomes, which are not known to be involved in HPV intracellular trafficking, are generated by MVB sorting processes (step 6i).

- Step 7i: L2 membrane penetration and cytosolic domain exposure result in recruitment of the retromer complex. Retromer and Rabs 6a, 7b, and 9a are involved in the transport of L2/vDNA to the TGN. A part of the L1 protein is transported to the lysosome for breakdown (step 7ii).

- Step 8): L2-containing vesicles generated from the Golgi interface with microtubules via exposed L2 domains, enabling Rab6a-dependent transport of vDNA vesicles to the mitotic nucleus, where the L2/vDNA complex obtains access to PML bodies.

- Step 9: Thereafter, early viral transcripts are converted into early gene products, such as E2, which binds vDNA to mitotic chromosomes.

- Step 10: Localization to the mitotic chromosome facilitates the creation and maintenance of vDNA in dividing cells by granting vDNA access to the cellular transcription and replication machinery.

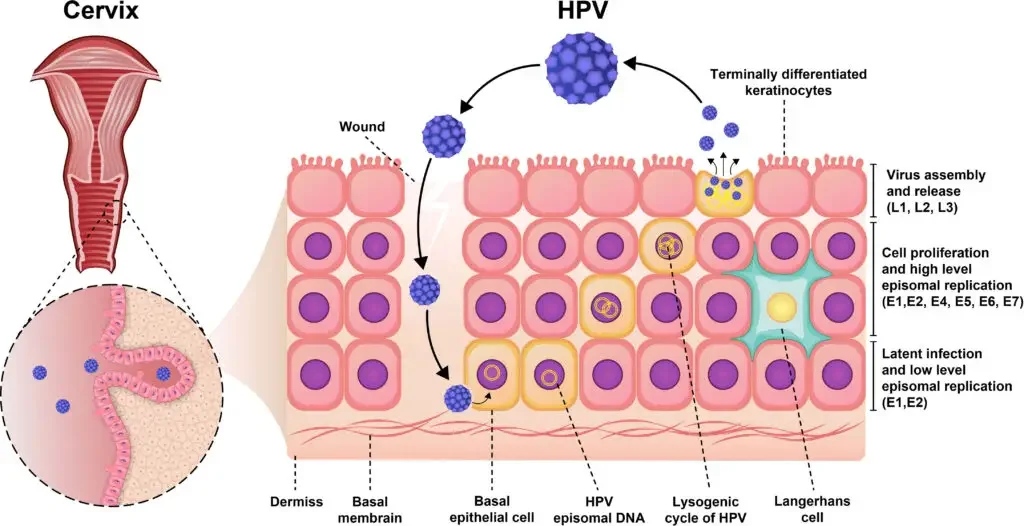

Pathogenesis of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- HPV are tiny, non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses that can infect mucosal and cutaneous epithelial cells. About eight open-reading frames are encoded in the HPV genome (ORFs).

- The ORFs consist of three functional regions: the early (E) region, the late (L) region, and the noncoding region or long control region (LCR). The E region genes encode proteins E1–E7 that are essential for viral replication and contribute to the pathogenesis of the virus.

- Capsid proteins L1 and L2 are encoded by the genes of the L region, which are essential for viral assembly. Moreover, LCR genes are essential for the replication and transcription of viral DNA and have a tropism towards epithelial cells.

- HPV can infect epithelial cells through contact with cell surface receptors such as integrin 6, which are highly expressed in basal cells and epithelial stem cells. Hence, a virus with a low copy number has the potential to infect primitive basal cells. Immediately after localized infection and viral DNA replication, the number of viruses within a cell rises to roughly 50–100 copies.

- To activate papillomavirus DNA replication, both E1 and E2 proteins are necessary. Initially, E1 as a dimer and E2 as a dimer bind to the viral origin, resulting to the formation of an E1–E2 ternary complex that inhibits the nonspecific binding of E1-DNA.

- This complex serves as a template for further molecular binding of E1 and E2 and assembly of the E1 double-trimer intermediate. In the end, double-hexameric E1 helicases with ATPase activity assemble, which are able to unwind DNA and interact with cellular DNA replication factors.

- Throughout the periods of plasmid and episomal maintenance, viral gene expression is limited. During the typical HPV life cycle, the expression of multiple viral oncogenes, including the E6 and E7 proteins, is tightly regulated.

- In addition, the expression of viral genes is markedly elevated when infected cells penetrate the various compartments of the cells, which are associated with cell growth. During viral DNA replication, there are at least one thousand copies of the virus per cell, and these virions promote the production of L1 and L2 capsid proteins as well as the assembly of infectious viruses.

- The characteristics of HPV’s life cycle play a crucial role in avoiding immune system detection and viral pathogenicity. HPV’s life cycle is distinguished by nonlytic immunity of infected cells and the absence of viremia and inflammatory signals.

Clinical Manifestations of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- Genital warts: These are one of the most common clinical manifestations of HPV. They may appear as small, raised, flesh-colored or grayish bumps in the genital area, including the penis, scrotum, anus, vulva, Genital passage, and cervix. Genital warts may be single or multiple, and may be flat or cauliflower-like in appearance.

- Cervical dysplasia: HPV infection can cause abnormal changes in the cells of the cervix, which is the lower part of the uterus that connects to the Genital passage. These changes may be mild, moderate, or severe, and are known as cervical dysplasia. In some cases, cervical dysplasia may progress to cervical cancer if left untreated.

- Cervical cancer: HPV infection is a major risk factor for cervical cancer, which is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide. Cervical cancer may cause symptoms such as abnormal Genital passage bleeding, pain during sex, or pelvic pain, but in many cases it may not cause any symptoms until it has advanced.

- Rectal cancer: HPV infection can also cause cancer of the anus, which is the opening at the end of the digestive tract through which stool passes out of the body. Rectal cancer may cause symptoms such as Rectal bleeding, pain, itching, or discharge.

- Other cancers: In addition to cervical and Rectal cancer, HPV infection can also cause other types of cancer, including cancer of the penis, vulva, Genital passage, oropharynx (the middle part of the throat behind the mouth), and tonsils.

It’s important to note that not all people with HPV infection will develop clinical manifestations, and that many people may have HPV without even knowing it. Regular screening for cervical cancer is recommended for women starting at age 21, and HPV vaccination is recommended for both boys and girls starting at age 11 or 12.

Diagnosis of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

Diagnosing Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection involves several methods, including:

- Pap smear: A sample of cells is taken from the cervix and examined under a microscope to check for abnormal cells. If abnormal cells are found, the sample may be tested for HPV.

- HPV DNA testing: A sample of cells from the cervix is tested to see if it contains HPV DNA.

- Colposcopy: A visual examination of the cervix using a colposcope, which is a special instrument that allows the healthcare provider to see any abnormal areas of the cervix more clearly.

- Biopsy: If abnormal cells are found during a Pap smear or colposcopy, a small sample of tissue may be taken from the cervix for examination under a microscope.

- HPV genotyping: This test can identify which type or types of HPV are present in the sample.

- HPV mRNA testing: This test can detect the presence of viral RNA, which is a sign of active HPV infection.

It’s important to note that there is no routine test to detect HPV in men, and testing for HPV in the mouth or throat is not routine. In cases where a person has visible warts, a healthcare provider may be able to diagnose the infection based on appearance alone.

Treatment of HPV

There is no specific treatment available for HPV infection itself. However, the following treatments can help manage the symptoms and related health problems caused by HPV:

- Topical medications: Some topical medications like imiquimod and podophyllin can help treat genital warts caused by certain types of HPV.

- Surgical procedures: Surgical procedures like cryotherapy, electrocautery, and laser therapy can help remove warts or precancerous lesions.

- Monitoring: In some cases, HPV infections can go away on their own without any treatment. Close monitoring of the infected area may be recommended in such cases.

- Prevention: Vaccines are available to protect against certain types of HPV that can cause genital warts and cervical cancer. Safe sex practices like using condoms can also help prevent the transmission of HPV.

Vaccination of HPV

- Vaccination: HPV vaccination is recommended for both males and females before the onset of sexual activity, as it is most effective before exposure to the virus.

- Safe sex practices: Condom use can reduce the risk of HPV transmission, but does not provide complete protection as the virus can be present in areas not covered by a condom.

- Regular screening: Regular screening for cervical cancer in females, through Pap tests or HPV testing, can detect and treat pre-cancerous changes in the cervix before they progress to cancer.

- Early treatment: Early treatment of genital warts and precancerous changes in the cervix can reduce the risk of progression to cancer.

- Education: Raising awareness about the risks of HPV infection, the importance of vaccination, and safe sex practices can help prevent the spread of the virus.

FAQ

What is human papillomavirus (HPV)?

HPV is a common virus that can be transmitted through sexual contact. It can cause various types of infections, some of which can lead to cancer.

What are the symptoms of HPV?

Most people with HPV do not experience any symptoms. However, some strains of the virus can cause genital warts or abnormal changes in cervical cells.

How is HPV diagnosed?

HPV can be diagnosed through a physical exam, Pap smear, or HPV DNA test. These tests can detect the presence of the virus or any changes in the cells that may indicate an infection.

Can HPV be treated?

There is no cure for HPV, but the symptoms of the infection can be treated. Treatment may include topical medications or procedures to remove genital warts or abnormal cells.

Can HPV lead to cancer?

Yes, some strains of HPV can cause cancer, including cervical, Rectal, and oropharyngeal cancer. Regular screening and vaccination can help prevent these types of cancer.

Who should get the HPV vaccine?

The HPV vaccine is recommended for both males and females between the ages of 9 and 45. Ideally, it should be given before any sexual activity.

Is the HPV vaccine safe?

Yes, the HPV vaccine is safe and effective. Like any vaccine, it may cause mild side effects, such as soreness at the injection site, but serious side effects are rare.

Can you get HPV if you use condoms?

Condoms can reduce the risk of HPV transmission, but they do not provide complete protection. The virus can be transmitted through skin-to-skin contact.

How can you prevent HPV?

The best way to prevent HPV is to get vaccinated, practice safe sex, and limit your number of sexual partners. Regular screening can also help detect any infections early.

Is HPV contagious?

Yes, HPV is highly contagious and can be spread through sexual contact, including Genital passage, Rectal, and oral sex. It can also be spread through skin-to-skin contact.

References

- Fernandes, Jos� & Fernandes, Thales. (2012). Human Papillomavirus: Biology and Pathogenesis. 10.5772/27154.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human Papillomaviruses. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007. (IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 90.) 1, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321770/

- Zgura AF, Bratila E, Vladareanu S. Transplacental Transmission of Human Papillomavirus. Maedica (Bucur). 2015 Jun;10(2):159-162. PMID: 28275411; PMCID: PMC5327801.

- Lee, Sung-Jong & Yang, Andrew & Wu, T.C. & Hung, Chien-Fu. (2016). Immunotherapy for human papillomavirus-associated disease and cervical cancer: Review of clinical and translational research. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology. 27. 10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e51.

- McBride, A. (2017). Mechanisms and strategies of papillomavirus replication. Biological Chemistry, 398(8), 919-927. https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2017-0113

- Kadaja, M., Silla, T., Ustav, E., & Ustav, M. (2009). Papillomavirus DNA replication — From initiation to genomic instability. Virology, 384(2), 360–368. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.032

- Bordignon V, Di Domenico EG, Trento E, D’Agosto G, Cavallo I, Pontone M, Pimpinelli F, Mariani L, Ensoli F. How Human Papillomavirus Replication and Immune Evasion Strategies Take Advantage of the Host DNA Damage Repair Machinery. Viruses. 2017; 9(12):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/v9120390

- Man, Stephen. (1998). Human cellular immune responses against human papillomaviruses in cervical neoplasia. Expert reviews in molecular medicine. 1998. 1-19. 10.1017/S1462399498000210.

- https://www.cancer.org/healthy/cancer-causes/infectious-agents/hpv.html

- https://www.health.gov.au/diseases/human-papillomavirus-hpv

- https://viralzone.expasy.org/5.html?outline=all_by_species

- https://www.news-medical.net/health/HPV-Transmission.aspx

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/human-papilloma-virus-hpv/

- https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/CMR.05028-11

- https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

- https://labpedia.net/human-papillomavirus-hpv-diagnosis-and-treatment/