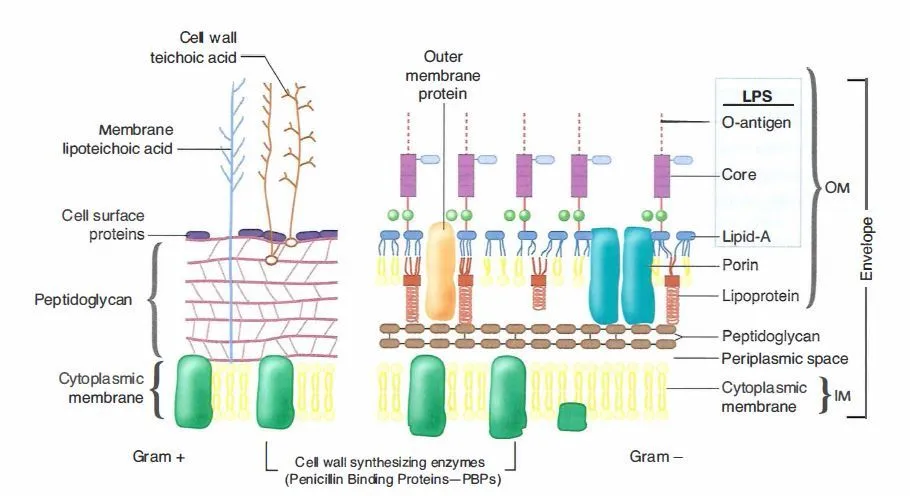

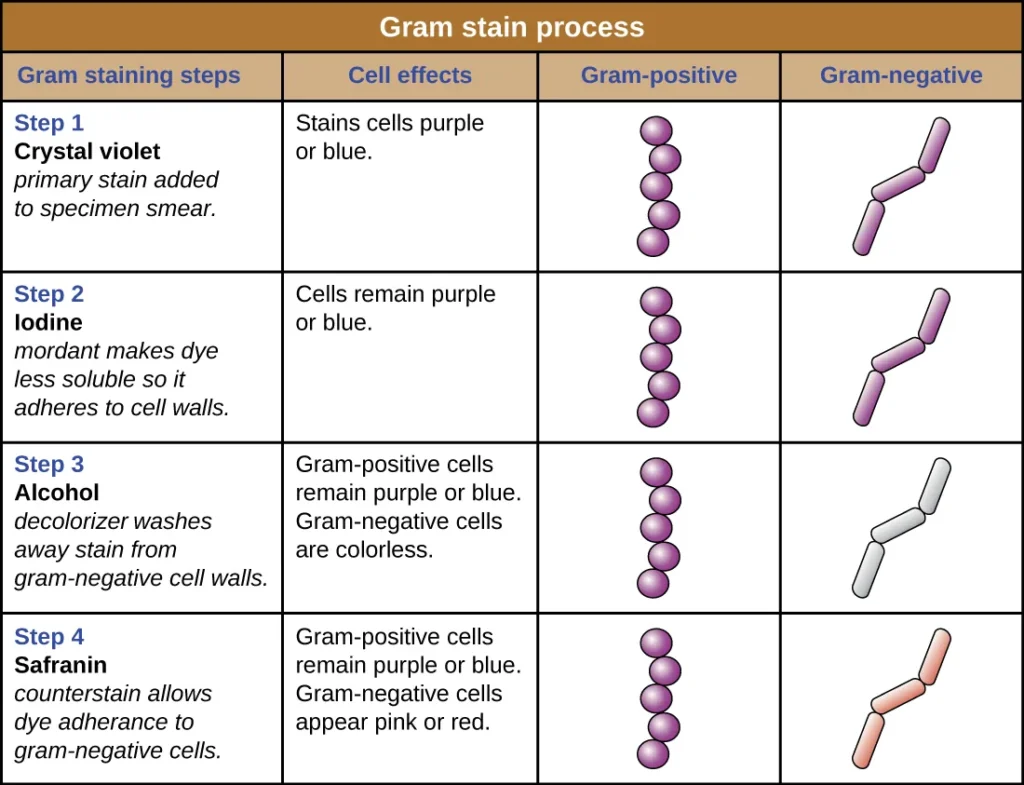

Gram staining is the differential staining technique used to separate bacteria into two major groups on the basis of their cell wall. It is the process where the bacterial cell is treated with a series of stains and reagents so that Gram-positive cells appear purple and Gram-negative cells appear pink. It is one of the most important basic procedures in bacteriology because the reaction is directly linked with the chemical nature of the peptidoglycan layer. Gram-positive bacteria have a thick multi-layered peptidoglycan which strongly retains the crystal violet–iodine complex, while Gram-negative cells have thin peptidoglycan along with an outer lipid membrane which is dissolved during decolorization, so the primary stain is lost and the counterstain is taken.

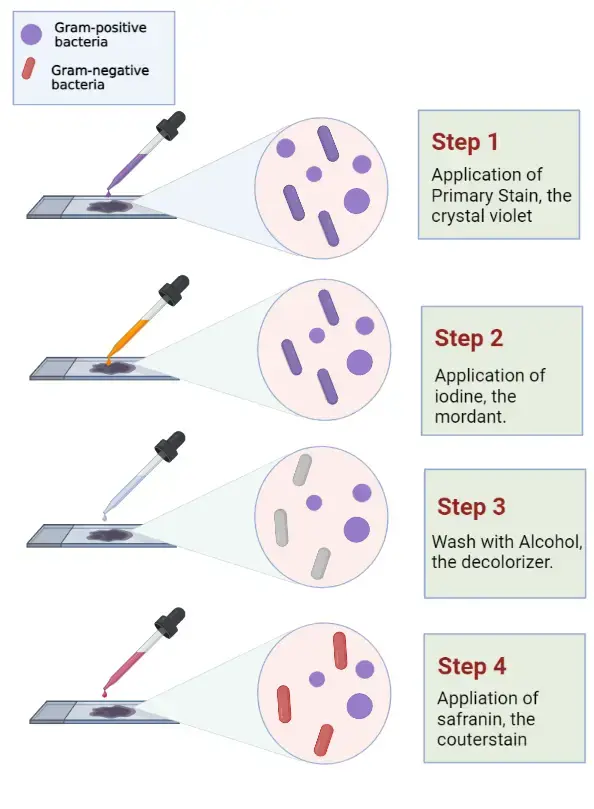

In this process the staining occurs in four steps where crystal violet acts as the primary stain. After this iodine is added which forms a crystal violet–iodine complex inside the cell. In the next step alcohol or acetone is added as the decolorizing agent, and this step is important because it differentiates the cells depending on the wall structure. The final step uses safranin as the counterstain which stains the decolorized Gram-negative cells. It is seen that the Gram staining gives information within minutes and it is used to identify the morphology of bacteria (cocci, bacilli) and also to guide the initial treatment in many infections. It is the process that is used routinely in laboratories because it provides the first idea about the type of bacteria present and also shows the host response by the presence of white blood cells in the smear.

History of Gram Staining

The history of Gram staining is the development of a simple staining method into one of the basic procedures of bacteriology. It is the process that started in 1884 when Hans Christian Gram was working in the morgue of a Berlin hospital. It is seen that Gram was searching for a way to visualize cocci present in lung tissue of pneumonia patients, and not to classify bacteria into groups. He used gentian violet as primary stain, Lugol’s iodine as mordant, ethanol as decolorizer and Bismarck brown as counterstain, and this sequence showed that some bacteria retained the stain while others were easily decolorized. In his short report he mentioned this difference but did not use the terms Gram-positive or Gram-negative, he only described that the staining reaction was not the same in all bacterial cells.

It is the method whose principle remained the same but reagents changed slowly. It is seen that crystal violet replaced gentian violet because it gave more stable staining. Some of the important modifications are Hucker’s modification where ammonium oxalate is added to prevent dye precipitation, and Burke’s modification where sodium bicarbonate acts as buffer. In place of Bismarck brown, modern staining uses safranin or basic fuchsin, and basic fuchsin is helpful because it stains Gram-negative cells more strongly which helps in detecting bacteria like Haemophilus spp. and Legionella spp. which stain poorly in routine methods.

During the 1980s Gram staining was used as point-of-care test by many physicians. It is reported that almost half of the internists in the United States performed their own Gram staining in routine practice. But this practice declined when the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA 1988) required special laboratory credentials for interpreting Gram stains, and many clinicians stopped doing the test. At the same time the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics increased and physicians treated infections such as pneumonia empirically, so the immediate need for Gram staining was reduced. By 2004 only a very small percentage of physicians were doing Gram stains personally.

It is noted that this method remained in clinical use in Japan because of continuous medical training at Okinawa Chubu Hospital. This hospital kept the practice active even after administration changed in 1972, and physicians continued to learn Gram staining as part of routine diagnosis. Some of the important studies from Japan showed that regular Gram staining helped in reducing unnecessary use of broad-spectrum antibiotics like carbapenems and anti-MRSA drugs, and without affecting patient outcome. This created renewed interest in using Gram staining as a tool for antimicrobial stewardship.

Today it is considered the basic staining technique in microbiology laboratories. It is used because the result is obtained quickly while culture methods need 2–5 days. It is the process that also guides the first selection of antibiotics by showing Gram-positive cocci or Gram-negative rods, and it works together with modern methods such as MALDI-TOF and PCR which need more cost or sample preparation. Thus the Gram staining remains the initial step that directs the further identification of bacterial pathogens.

Definition of Gram Staining

Gram staining is a microbiological technique used to differentiate bacterial species into two groups, gram-positive and gram-negative, based on the chemical properties of their cell walls.

Gram Staining Principle

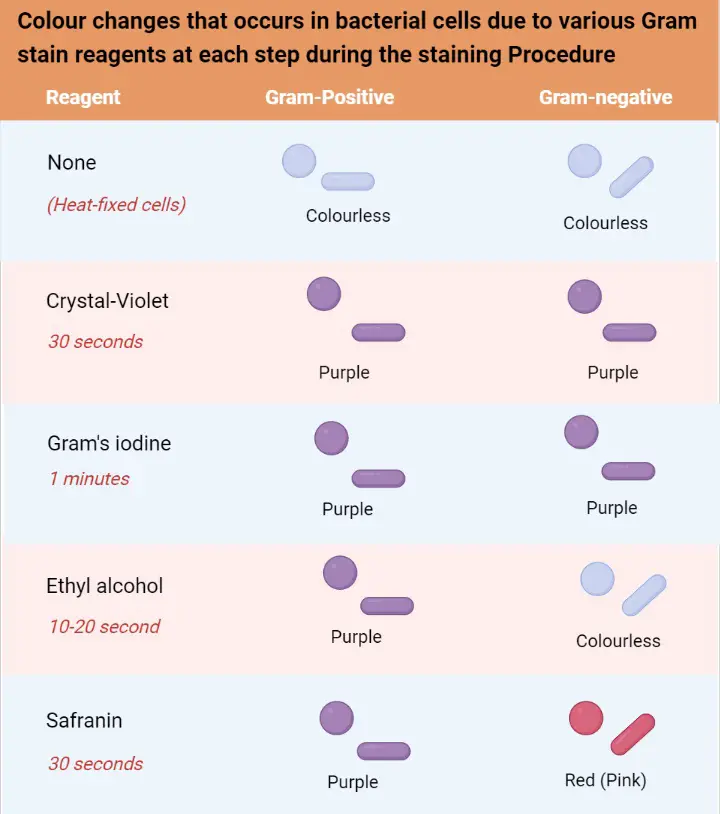

The principle of Gram staining is based on the fundamental differences present in the cell wall of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It is the process where the thick peptidoglycan of Gram-positive cells and the thin peptidoglycan along with lipid-rich outer membrane of Gram-negative cells respond differently to the staining reagents. It is seen that Gram-positive bacteria possess a multi-layered peptidoglycan which forms almost the major part of the cell envelope and this structure helps in retaining the primary stain, while the Gram-negative cells have a thin peptidoglycan layer which is not able to hold the stain strongly once the outer membrane is disrupted during decolorization. Thus the principle depends on how the dyes interact with these structures and how the permeability of the cell wall changes during each step.

In this stepwise process crystal violet (CV) enters both types of cells because it is a basic dye. It is followed by iodine which acts as the mordant and makes a crystal violet–iodine (CV–I) complex inside the cell. This complex is large and insoluble and at this stage both Gram-positive and Gram-negative cells appear purple. It is the next step where the differentiation occurs, because alcohol or acetone is added which dehydrates the thick peptidoglycan layer of Gram-positive bacteria, making the pores narrow and trapping the CV–I complex inside. In contrast the Gram-negative outer membrane is dissolved by the alcohol due to its lipid content, and the thin peptidoglycan layer cannot retain the CV–I complex, so the stain is washed out.

After decolorization the Gram-negative cells become colorless and a counterstain like safranin is used to stain these cells pink. Gram-positive cells also take up the counterstain, but the intense purple color of crystal violet masks this. It is seen that the accuracy of the Gram staining principle depends on the age and condition of the bacterial culture, because older Gram-positive cells may lose their ability to retain the primary stain and appear Gram-variable. Thus the principle of Gram staining depends mainly on cell wall structure, dye retention, and the effect of decolorizing agents which produce clear differentiation between the two groups.

Requirements for Gram Staining

- Microscope Slide – A clean glass slide is needed for preparing the smear.

- Inoculation Loop – It is used to transfer the culture or water drop on the slide.

- Heat Source – A Bunsen burner or hot plate is required for heat-fixing the smear which kills the cells and helps in sticking them to the slide.

- Slide Rack – It is used to hold the slide during staining and washing steps.

- Microscope – A brightfield microscope with oil immersion (100x) is required for observation.

- Bibulous Paper – This paper is used to blot the slide dry after washing.

- Water – Tap water or distilled water is needed for rinsing at different steps.

- Crystal Violet – It is the primary stain used first to colour all the cells purple.

- Gram’s Iodine – This acts as the mordant. It forms the CV-I complex inside the cell.

- Decolorizer – Acetone, ethanol (95%) or a mixture is required to remove the stain from Gram-negative cells.

- Counterstain (Safranin or Basic Fuchsin) – Safranin stains Gram-negative cells pink. Basic fuchsin is also used and gives stronger staining in some bacteria.

- Aseptic Collection of Specimen – The sample must be collected properly to avoid contamination.

- Smear Thickness – The smear must be thin and spread evenly. It should be readable through the slide.

- Age of Culture – Young cultures are required since older cells may lose wall integrity and give false Gram-negative reaction.

- Control Organisms – A known Gram-positive and Gram-negative organism is used on the same slide to check the staining accuracy.

Gram Stain Reagents

1. Crystal Violet Reagent (Primary Stain) – It is the stain used first and gives the initial purple colour to all cells.

- Solution A is prepared by dissolving 2 g crystal violet in 20 ml ethanol (95%).

- Solution B is prepared by dissolving 0.8 g ammonium oxalate in 80 ml distilled water.

- Both the solutions is mixed together to make the staining reagent. It is kept for 24 hours and then filtered before use.

2. Gram’s Iodine (Mordant) – It is the reagent which forms the crystal violet–iodine complex inside the cell.

- The reagent contains 1 g iodine, 2 g potassium iodide and 300 ml distilled water.

- The iodine and potassium iodide is ground together, and water is added slowly until the iodine dissolves completely.

- It is stored in dark bottles to prevent breakdown by light.

3. Decolorizer – It is the reagent which removes the stain from Gram-negative cells while retaining it in Gram-positive cells.

- 95% ethanol can be used as the decolorizer.

- A mixture of acetone and ethanol (50 ml acetone + 50 ml ethanol) is also used.

- Acetone alone acts very fast and can also be used.

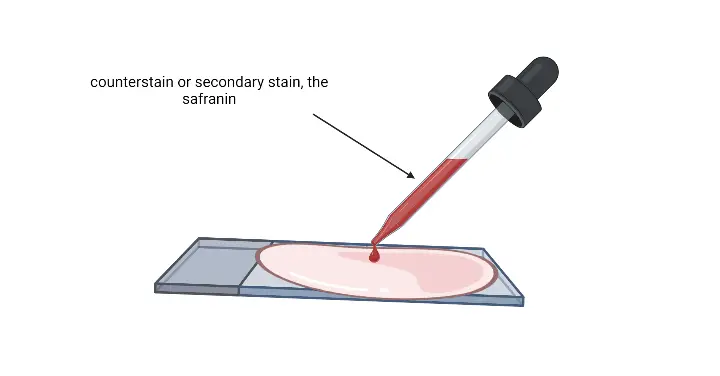

4. Counterstain (Safranin or Basic Fuchsin) – It stains the decolorized Gram-negative cells.

- Safranin stock solution is made by dissolving 2.5 g safranin in 100 ml ethanol (95%).

- The working solution is prepared by adding 10 ml of this stock to 90 ml distilled water.

- Basic fuchsin (0.1–0.2%) is also used and gives stronger staining in some Gram-negative bacteria.

Gram Staining Reagents Preparation

- Crystal Violet (Primary stain)

- Solution A is prepared by dissolving 2 g crystal violet in 20 ml 95% ethanol.

- Solution B is prepared by dissolving 0.8 g ammonium oxalate in 80 ml distilled water.

- It is mixed after both solutions are made.

- The mixture is kept for 24 hours and it is filtered before use.

- Gram’s Iodine (Mordant)

- Ingredients are 1 g iodine, 2 g potassium iodide, and 300 ml distilled water.

- Iodine and potassium iodide are ground together in a mortar.

- Water is added slowly until iodine dissolves.

- It is stored in amber bottles as light affects the reagent.

- Decolorizing Agent

- Acetone–ethanol mixture is prepared by mixing 50 ml acetone and 50 ml 95% ethanol.

- 95% ethanol alone is also used as a slow decolorizer.

- Pure acetone is used when rapid decolorization is required.

- Counterstain (Safranin option)

- Stock solution is made by dissolving 2.5 g Safranin O in 100 ml 95% ethanol.

- Working solution is prepared by adding 10 ml stock into 90 ml distilled water.

- Counterstain (Basic Fuchsin option)

- A 0.1–0.2% solution of basic fuchsin is prepared.

- It is used mostly when Gram-negative organisms need intense staining.

- General points

- Reagents are filtered if precipitates appear, as dye deposits mimic bacteria.

- Fresh reagents are preferred.

- Older reagents are always filtered before use.

Gram Staining Procedure

a. Preparation of a Slide Smear for Gram Staining

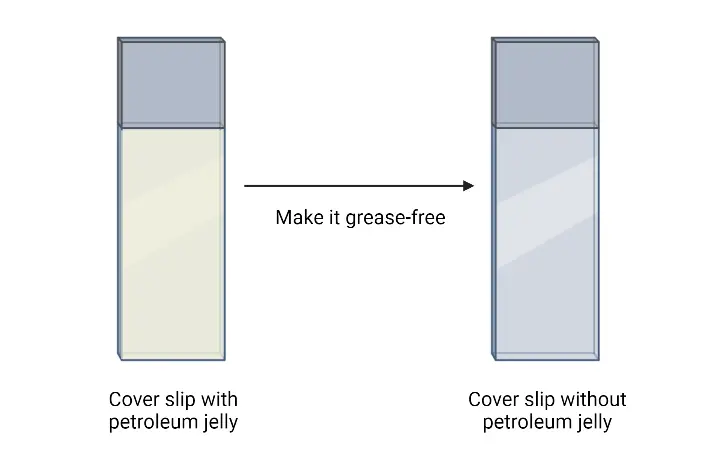

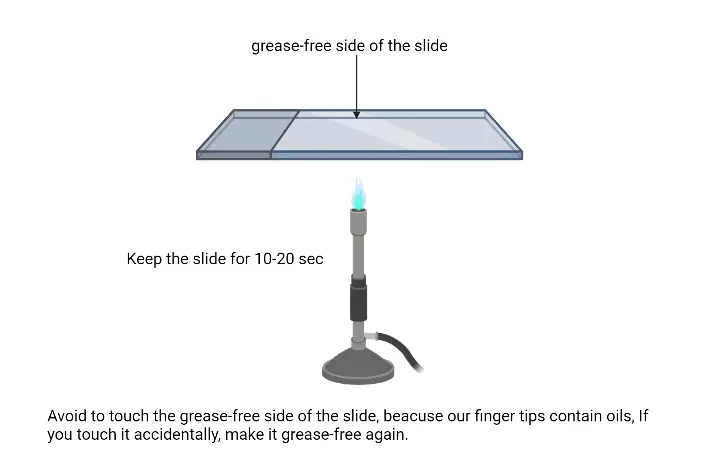

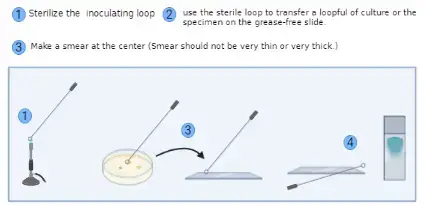

- Prepare the glass slide– It is important to use a clean and grease-free slide. The slide is wiped properly so that no dust or oil is present.

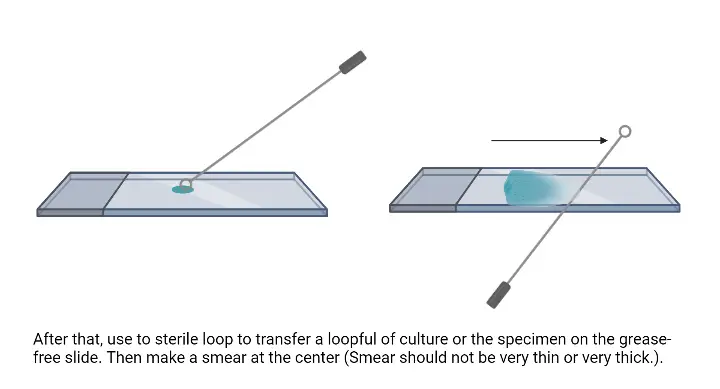

- Transfer the bacterial culture– From suspension, the inoculating loop is first sterilized by flaming and then one loopful of culture is placed at the centre of the slide. From solid media, a small drop of water is placed on the slide and a small amount of colony is mixed with the water using a sterile loop.

- Prepare the smear– The suspension is spread gently with the loop. It is the process of making a thin smear because thick smear is not suitable for observing the cells clearly.

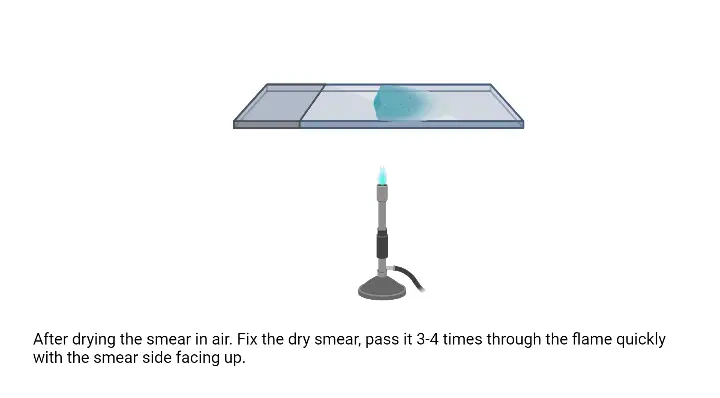

- Air dry the smear– The smear is allowed to dry in air. It is dried completely so the cells adhere on the slide surface.

- Fix the smear– The dried slide is passed over the flame gently. It is moved quickly above the flame to avoid overheating. This is referred to as heat fixation and it helps in attaching the cells so they do not wash away during staining.

b. Gram Staining Protocol

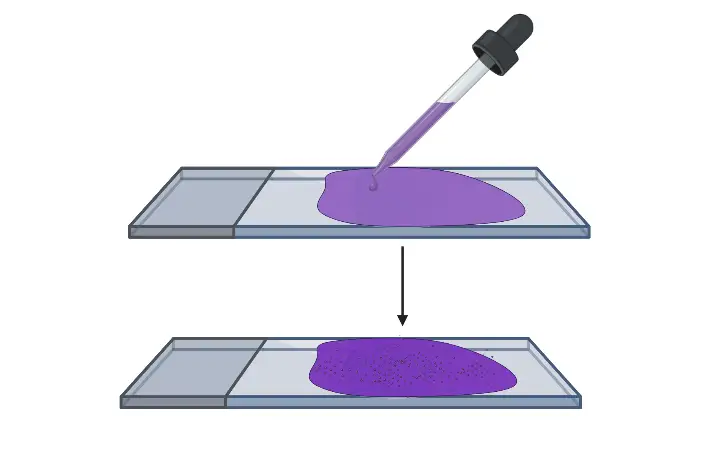

- Flood crystal violet over fixed smear– It is the primary stain and the whole smear is covered properly. The stain is kept for 30–60 seconds.

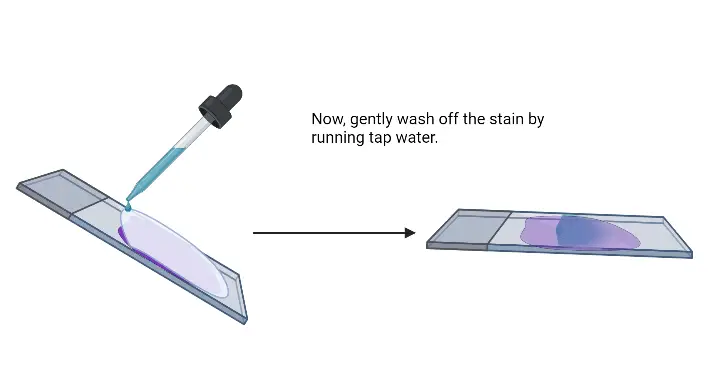

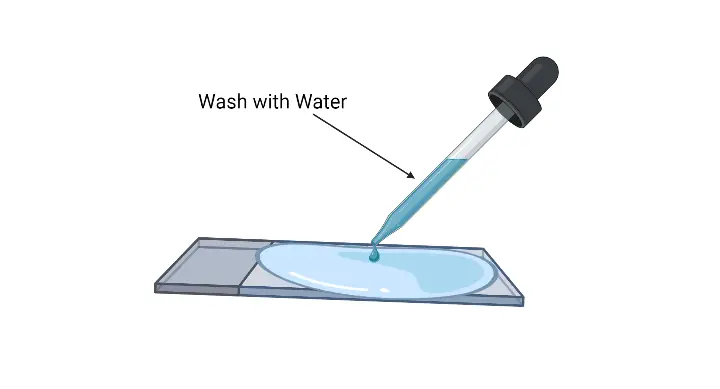

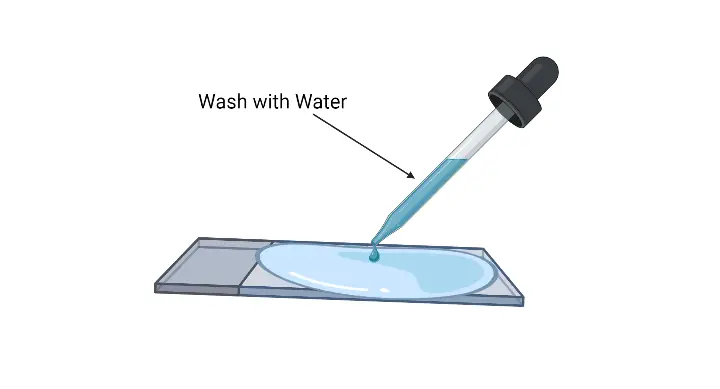

- Rinse the slide– The excess crystal violet solution is poured off and the slide is washed gently with running water.

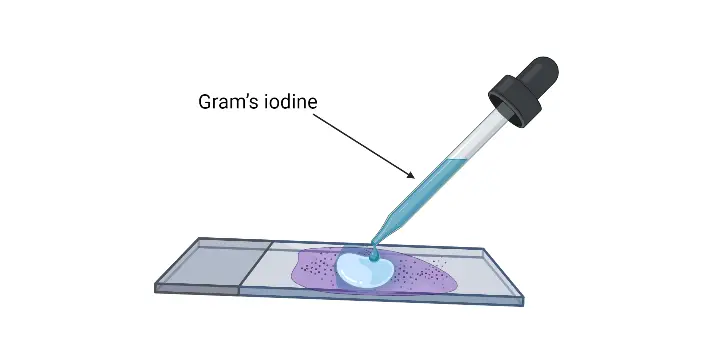

- Flood the smear with Gram’s iodine– It is the mordant and it is kept for 30–60 seconds so that the crystal violet–iodine complex is formed.

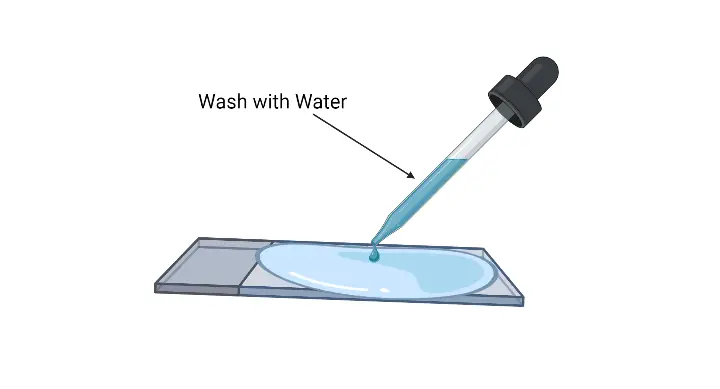

- Rinse the slide– The excess iodine is removed and the slide is rinsed with gentle running water.

- Shake off excess water–It removes the extra water before decolorizing.

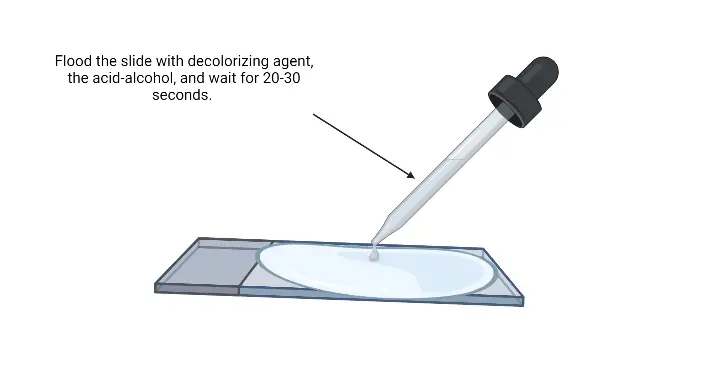

- Decolorize the smear– It is the step where the slide is passed through decolorizing solution till the solution runs clear. Alternatively, a few drops are added and shaken gently and rinsed after 5 seconds with distilled water. It is the process that differentiate Gram positive and Gram negative cells.

- Rinse with distilled water– It washes off residual decolorizer.

- Shake off excess water– It helps in preparing the smear for counterstaining.

- Pour safranin as counterstain– The whole smear is covered and left for 30–60 seconds. Gram negative cells is stained in this step.

- Wash with gentle running water– Excess safranin is removed.

- Air dry or blow-dry the slide– The smear is dried completely before microscopic observation.

b. Procedure of Microscopic Observation of Gram Stain

(Simple list format, written strictly in Sourav’s PDF style)

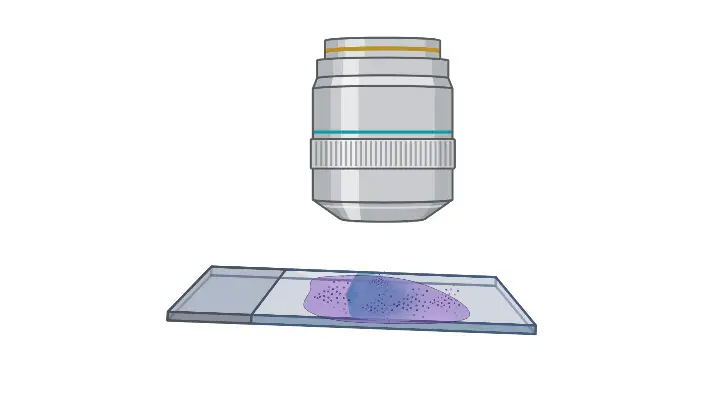

- Place the slide on the stage– The Gram-stained air-dried smear is kept on the stage of the compound microscope and fixed properly with stage clips so it does not move.

- Focus the light– The stage is adjusted so that proper light falls over the smear. It is important for clear visibility of cells.

- Set the 10X objective– The 10X objective lens is aligned and the smear is focused using the coarse adjustment knob. It gives a broad view of the smear.

- Shift to 40X objective– The objective lens is changed to 40X and the smear is focused using the fine adjustment knob for a clearer view.

- Prepare for oil immersion– The nose piece is rotated so that the smear falls between 40X and 100X objectives. A drop of immersion oil is added over the smear.

- Align the 100X oil immersion lens– The nose piece is rotated again and the 100X oil immersion lens is placed over the smear.

- Final focusing– The fine adjustment knob is used to focus the smear properly.

- Study the bacteria– The cells are observed for colour, shape, and arrangement to identify Gram positive or Gram negative bacteria.

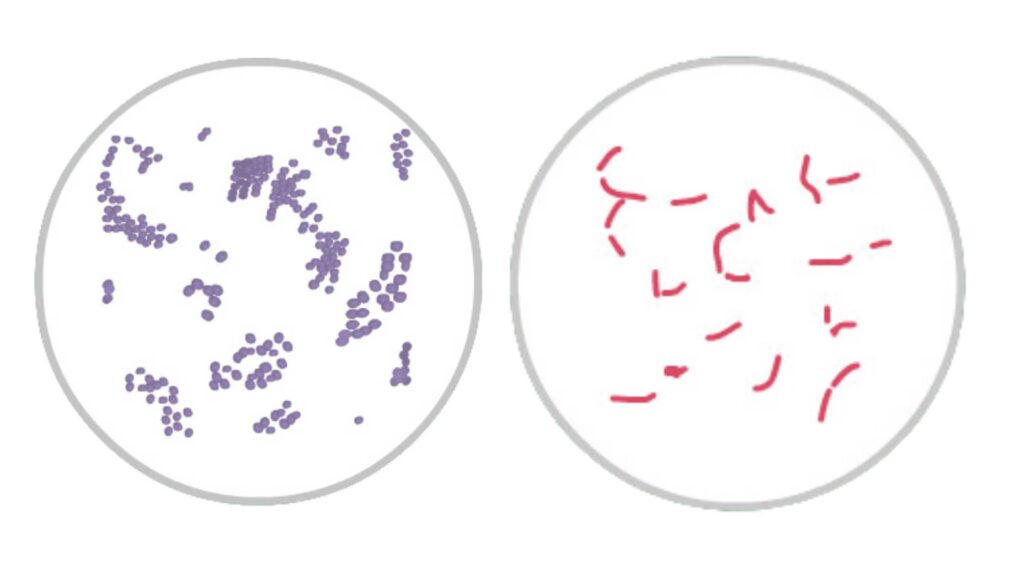

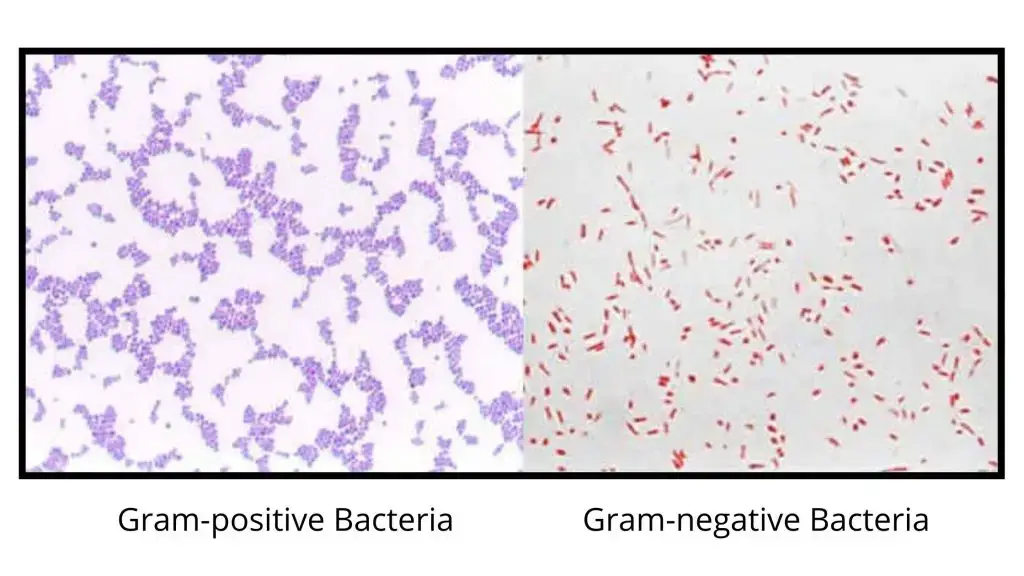

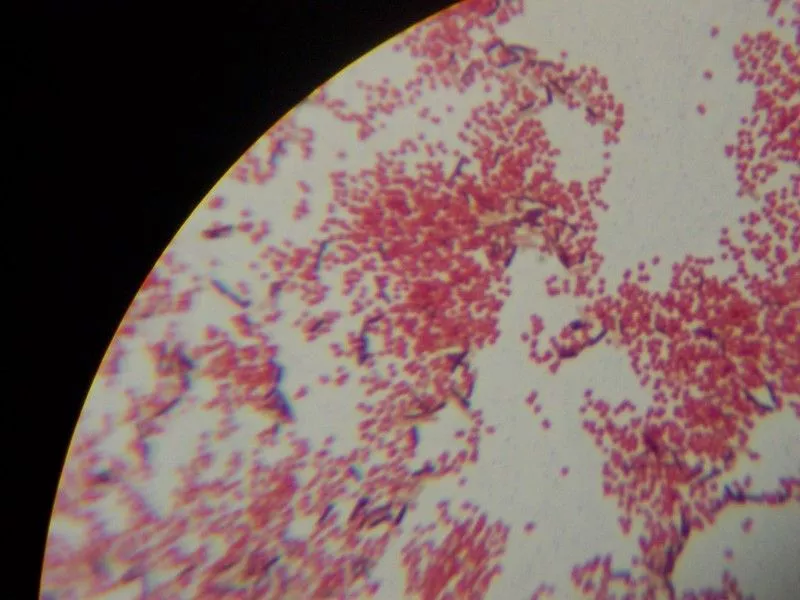

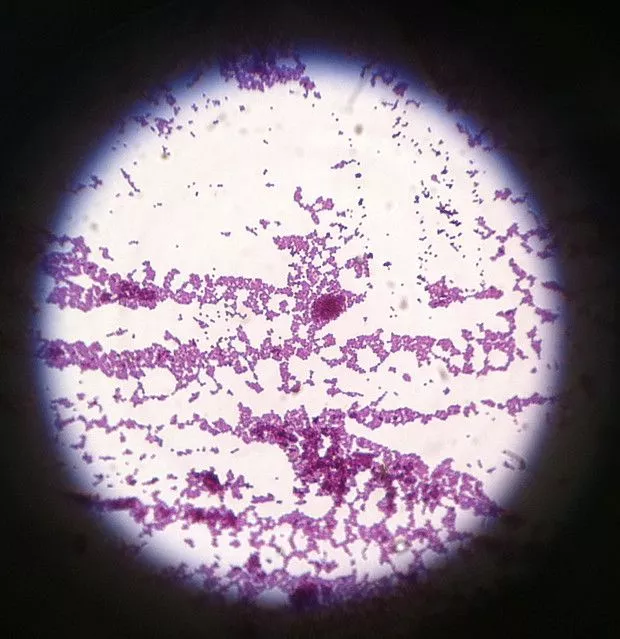

Gram Staining Result and Interpretation

- Gram-positive reaction– These cells appear blue or purple. It is the result of a thick peptidoglycan layer which retains the crystal violet–iodine complex during decolorization.

- Gram-negative reaction– These cells appear pink or red. The thin peptidoglycan and lipid-rich outer membrane allow the primary stain to escape, so the cells take the counterstain.

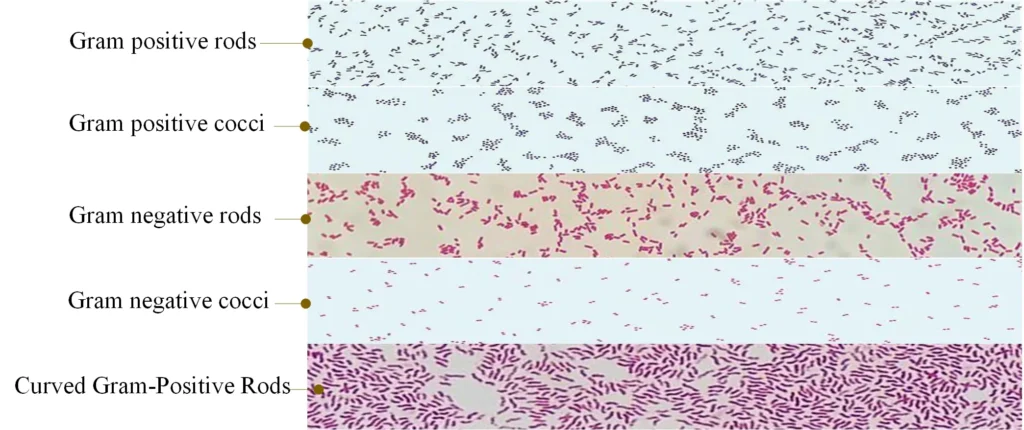

- Cell morphology– The smear is observed for cocci, bacilli, or coccobacilli. It is the step for understanding basic bacterial shape.

- Arrangement of cells– Clusters, chains, pairs, or tetrads is seen in Gram-positive cocci. Rods, curved rods, or diplococci is seen in Gram-negative bacteria.

- Host response indicator– Presence of neutrophils or macrophages is seen as pink-stained cells, indicating active infection. Squamous epithelial cells appear Gram-positive and indicate contamination in respiratory samples.

- Specimen quality– A good smear shows clear background without too much debris. Excess epithelial cells show poor-quality specimen.

- Gram-variable result– Some cells appear both pink and purple. This occurs in older cultures where the wall becomes weak and cannot hold the stain.

- False reactions– Over-decolorizing may cause Gram-positive cells to appear Gram-negative. Thick smears can resist decolorization and appear falsely Gram-positive.

- Non-staining organisms– Organisms without cell walls like Mycoplasma do not appear in Gram staining.

Examples of Gram-positive and Gram-negative Bacteria

- Gram-positive cocci– Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp.

- Gram-positive bacilli– Bacillus spp., Clostridium spp., Lactobacillus spp., Streptomyces spp., Listeria spp., Corynebacterium spp.

- Gram-negative cocci– Neisseria spp., Moraxella spp., Acinetobacter spp.

- Gram-negative bacilli– E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp.

| Gram-Positive Bacteria | Gram-Negative Bacteria |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Escherichia coli |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Salmonella spp. |

| Bacillus anthracis | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Clostridium tetani | Proteus mirabilis |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Haemophilus influenzae |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Shigella spp. |

| Clostridium perfringens | Vibrio cholerae |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Francisella tularensis |

Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria

Gram positive cocci

| Description of the Morphotype | Most Common Organisms |

| Pairs | Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus spp. |

| tetrads | Micrococcus, Staphylococcus, Peptostreptococcus spp |

| Groups | Staphylococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Stomatococcus spp. |

| Chains | Streptococcus, Peptostreptococcus spp. |

| Clusters, intracellular | Streptococcus spp. Microaerophilic, viridans streptococci, Staphylococcus spp. |

| Encapsulated | Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes (rarely), Stomatococcus mucilaginosus |

| In the form of an ancestor | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

Gram-negative cocci

| Neisseria spp., Moraxella catarrhalis. |

Gram-positive bacilli

| Description of the Morphotype | Most Common Organisms |

| Little | Listeria monocytogenes, Corynebacterium spp. |

|---|---|

| Medium | Lactobacillus, anaerobic bacilli |

| Big | Clostridium, Bacillus spp. |

| Diphtheroid | Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Rothia spp. |

| Pleomorphic, Gram variables | Gardnerella vaginalis |

| Pearl | Mycobacteria, lactobacilli affected by antibiotics and corynebacteria |

| Filamentous | Anaerobic morphotypes, cells affected by antibiotics |

| Filamentous, beaded, branched | Actinomycetes, Nocardia, Nocardiopsis, Streptomyces, Rothia spp. |

| Bifid or V shapes | Bifidobacterium spp., brevibacteria |

| Gram-negative coccobacilli | Bordetella, Haemophilus spp. (pleomorph) |

| Masses | Veillonella spp. |

| Chains | Prevotella, Veillonella spp. |

Gram-negative bacilli

| Description of the Morphotype | Most Common Organisms |

| Little | Haemophilus, Legionella (thin with filaments), Actinobacillus, Bordetella, Brucella, Francisella, Pasteurella, Capnocytophaga, Prevotella, Eikenella spp. |

|---|---|

| Bipolar | Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pasteurella spp., Bacteroides spp. |

| Medium | Enterics, pseudomonads |

| Big | Clostridia or devitalized bacilli |

| Curved | Vibro, Campylobacter spp. |

| Spiral | Campylobacter, Helicobacter, Gastrobacillum, Borrelia, Leptospira, Treponema spp |

| Fusiform | Fusobacterium nucleatum |

| Filaments | Fusobacterium necrophorum (pleomorph) |

Applications of Gram Staining

- It is used for rapid diagnosis in acute infections because the stain gives immediate information about the nature of bacteria present and this helps in early decision of treatment.

- It is useful for examining sterile body fluids like cerebrospinal fluid or synovial fluid where the presence of Gram-positive cocci or Gram-negative rods indicate the type of pathogen responsible.

- It is the process that helps in selecting empirical antibiotics in emergency cases, as the stain guides whether broad-spectrum drugs are required or the treatment can be narrowed.

- It is used in antimicrobial stewardship since it reduces unnecessary use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and helps in choosing selective drugs based on Gram reaction.

- It is applied in studying different clinical specimens like sputum in pneumonia, urine in urinary tract infections, and wound swabs in soft tissue infections.

- It is also used to examine urogenital samples to detect organisms like Neisseria gonorrhoeae and in detecting yeast cells like Candida in fungal infections.

- It indicates specimen quality by showing presence of neutrophils or epithelial cells which helps in understanding host response.

- It is the first step for laboratory identification because it classifies the organism into Gram-positive or Gram-negative which then decide the biochemical tests or molecular methods to be used.

Advantages of Gram Staining

- It is the method that gives very rapid results and this is useful in acute infections where immediate diagnosis is required.

- It is able to guide early treatment decisions in cases like meningitis or septic arthritis because the stain shows the type of bacteria within minutes.

- It helps in selecting empirical antibiotics as the Gram reaction indicate whether broad-spectrum drugs are needed or the therapy can be narrowed.

- It reduces unnecessary use of antibiotics like carbapenems and anti-MRSA agents since the stain provide direction for targeted therapy.

- It is a cost-effective technique because the reagents and equipment required is simple and inexpensive compared to molecular tests.

- It is easy to perform and can be used in laboratories with limited facilities because no advanced instrument is required.

- It is useful for observing host inflammatory response since neutrophils and other cells can be seen in the smear.

- It indicates specimen quality by showing epithelial cells or contamination, and this help in deciding if the sample is adequate.

- It gives information about morphology and arrangement of bacteria (cocci or rods, clusters or chains) which help in early identification before culture.

Limitation of Gram Staining

- It is unable to detect bacteria that has no cell wall like Mycoplasma, so these organisms is not stained by the reagents.

- It is not suitable for intracellular and very small bacteria such as Chlamydia and Rickettsia which cannot be seen clearly under this method.

- It is difficult to stain Mycobacterium species because their wall is rich in mycolic acid, and this repel the aqueous dyes, so acid-fast staining is required instead.

- It is common to get Gram-variable results when the culture becomes old because the peptidoglycan layer becomes thin and cells may lose the primary stain.

- Some Gram-negative organisms like Acinetobacter resist decolorization, and it is seen as Gram-positive which create confusion.

- It is highly sensitive to operator handling because over-decolorization make Gram-positive cells appear pink, and under-decolorization make Gram-negative cells remain purple.

- It is affected by smear thickness since a thick smear prevent proper penetration and washing of dyes and lead to irregular staining.

- It may show artifacts like crystal violet precipitates which may be misinterpreted as Gram-positive cocci by inexperienced observers.

- It is not able to give species-level identification as it only tells Gram reaction and morphology, so it has limited diagnostic specificity.

- It cannot detect resistance genes or molecular characteristics which is possible by PCR-based methods.

- It has low sensitivity when bacterial load is low, or when antibiotics were taken which damage the cell wall and inhibit staining.

- Certain pathogens like Legionella and Haemophilus stain poorly with safranin and may be missed unless stronger counterstain is used.

Animation of gram staining

Gram Staining Images

FAQ

Q1. What is Gram staining?

A. It is a differential staining method where bacterial cells are treated with dyes to separate them into gram-positive and gram-negative groups based on their cell wall structure.

Q2. What is Gram staining used for?

A. It is used to classify bacteria, to detect their morphology, and to give quick diagnostic information in clinical samples.

Q3. What are gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria?

A. Gram-positive bacteria are those whose thick peptidoglycan layer retain the crystal violet stain, while gram-negative bacteria has a thin peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane so they do not retain the stain.

Q4. What do Gram stain results mean?

A. The results show whether the organism is gram-positive (purple) or gram-negative (pink), and also show the shape and arrangement which help in early identification.

Q5. When is a Gram stain performed?

A. It is performed when rapid diagnosis is required, especially in infections involving cerebrospinal fluid, urine, sputum, or wound samples.

Q6. What is the procedure for Gram staining?

A. The procedure involves preparing the smear, applying crystal violet, adding iodine, decolorizing with alcohol, and finally counterstaining with safranin.

Q7. What is the primary stain used in Gram staining?

A. The primary stain is crystal violet.

Q8. What is the role of iodine in Gram staining?

A. It is the mordant which form a crystal violet–iodine complex inside the cell to intensify the primary stain.

Q9. What color do gram-positive bacteria appear after Gram staining?

A. Gram-positive bacteria appear purple.

Q10. What color do gram-negative bacteria appear after Gram staining?

A. Gram-negative bacteria appear pink or red.

Q11. Why do gram-positive bacteria retain the crystal violet stain?

A. This occurs because their thick peptidoglycan layer becomes dehydrated during decolorization and trap the crystal violet–iodine complex.

Q12. Why do gram-negative bacteria appear pink or red?

A. The alcohol dissolves their outer membrane and the thin peptidoglycan cannot hold the primary stain, so they take up the safranin counterstain.

Q13. What’s the difference between a Gram stain and a bacteria culture?

A. Gram stain gives immediate microscopic information while culture requires growth of the organism and takes longer but provides species identification and antibiotic sensitivity.

Q14. How is the sample collected for Gram staining?

A. The sample is collected from body fluids, sputum, swabs, or urine and spread on a clean slide to prepare a smear.

Q15. Why might a gram-positive bacterium appear gram-negative under the microscope?

A. This happens when the culture is old or the cell wall is damaged, or if over-decolorization occur during the staining process.

- Arbefeville, S. S., Timbrook, T. T., & Garner, C. D. (2024). Evolving strategies in microbe identification—a comprehensive review of biochemical, MALDI-TOF MS and molecular testing methods. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 79(Suppl 1), i2–i8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkae275

- CellaVision. (2022). What are the main problems you encounter when Gram staining? https://www.cellavision.com/problems-Gram-staining

- Ito, H., Tomura, Y., Oshida, J., Fukui, S., Kodama, T., & Kobayashi, D. (2023). The role of gram stain in reducing broad-spectrum antibiotic use: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Infectious Diseases Now, 53(6), 104764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idnow.2023.104764

- Smith, A. C., & Hussey, M. A. (2005, September 30). Gram stain protocols. American Society for Microbiology. https://asm.org/getattachment/5c95a063-326b-4b2f-98ce-001de9a5ece3/gram-stain-protocol-2886.pdf

- Tripathi, N., Zubair, M., & Sapra, A. (2025). Gram staining. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562156/

- Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Gram stain. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gram_stain&oldid=1325757437

- Yoshimura, J., Ogura, H., & Oda, J. (2023). Can Gram staining be a guiding tool for optimizing initial antimicrobial agents in bacterial infections? Acute Medicine & Surgery, 10(1), e862. https://doi.org/10.1002/ams2.862

- https://asm.org/getattachment/5c95a063-326b-4b2f-98ce-001de9a5ece3/gram-stain-protocol-2886.pdf

- https://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/research_methods/microscopy/gramstain.html

- https://microbiologie-clinique.com/gram-stain-principle-steps-interpretation.html

Jay Hardy – Gram’s Serendipitous Stain - Andreia Popescu – The Gram Stain after More than a Century

- Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook 4ed

- TEXtBOOK Diagnostic Microbiology 4ed

- T J Beveridge – Mechanism of gram variability in select bacteria