What are Monocytes?

- Monocytes are an essential component of the immune system, operating as immune effector cells in both innate and adaptive immunological responses. These cells, which have chemokine receptors and pathogen recognition receptors, can be found circulating in the blood or concentrated in lymphoid organs.

- Monocytes have a three-day lifespan and account for about 5% of all circulating nucleated cells in human blood. They are extremely adaptable, since they can develop into macrophages and dendritic cells, becoming important actors in immune defense processes.

- Monocytes have a wide range of tasks, efficiently performing several roles that are normally performed by various immune cells. They have pattern recognition receptors that enable them to recognize danger signals or stimuli and participate in phagocytosis. Monocytes can also convey antigens to other cells and release chemokines and cytokines, so promoting immunological responses.

- These cells are formed from the bone marrow’s common myeloid progenitor cells. Monocytes, on the other hand, are recognized for their developmental plasticity, which means they can differentiate into other immune cells or even osteoclasts depending on the inflammatory response.

- Monocytes are found in all vertebrates, though their concentration in the bloodstream varies between species. They actively contribute in the defense against numerous infections produced by viruses, bacteria, fungus, or parasites as part of the innate immune system.

- Monocytes are mononuclear phagocytic cells with distinct morphological and physiological characteristics that change depending on their stage of differentiation. They are the most numerous type of leukocyte seen in circulation and constitute a type of leukocyte known as white blood cells. Monocytes have the amazing ability to develop into macrophages and dendritic cells, which contribute to the innate immune response while also impacting adaptive immunological responses and tissue healing.

- Monocytes in human blood are classified into several subclasses based on the phenotypic receptors they express, adding to their functional variety. Monocytes are produced by the bone marrow from precursor cells known as monoblasts, which are derived from hematopoietic stem cells.

- Monocytes circulate in the bloodstream for one to three days after being released before moving to various tissues throughout the body. They develop into macrophages and dendritic cells once in the tissues, increasing the immune response and boosting antigen presentation.

- Monocytes play an important part in the body’s defense against pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, and fungus. They are the largest form of white blood cell and are created in the bone marrow before being released into the bloodstream and tissues. Monocytes rapidly move to the site of infection in response to specific pathogens, contributing to the body’s defense mechanisms.

- Monocytes can differentiate into dendritic cells in addition to being macrophage progenitors. Dendritic cells are immune cells that capture antigens and present them to the immune system, boosting the body’s defense against infections. Monocytes are thus classified as antigen-presenting cells.

- Monocytes respond quickly to inflammatory signals in the body and can reach areas of infection or tissue injury within 8 to 12 hours. When they arrive at these locations, they differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells, offering an improved immune response to battle the threat.

- Monocytes’ surfaces contain unique proteins that allow them to interact with various types of viruses or bacteria, aiding in their identification by immune system cells. The presence of particular proteins in the blood facilitates this identification, which boosts the immune response and aids in the clearance of invading pathogens.

Definition of Monocytes

Monocytes are a type of white blood cell that serves as an immune effector cell. They are part of the innate immune system and play a critical role in phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and cytokine secretion. Monocytes differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells, contributing to immune defense against pathogens and tissue repair.

Structure of Monocytes

- Monocytes are the largest cells found in the peripheral blood, typically measuring between 14-20 µm in diameter. They have distinct morphological features, including an irregular cell shape and an oval or kidney-shaped nucleus. The cytoplasm of monocytes contains vesicles and numerous cytoplasmic granules, which are more concentrated near the cell membrane.

- The nucleus of a monocyte is prominent and folded, rather than multilobed like in other leukocytes. Inside the nucleus, there is a characteristic chromatin net with strands that bridge tiny chromatin clumps. These clumps are arranged on the inner side of the nuclear membrane.

- The cell membrane of monocytes is marked by ruffles and surface blebs, which have functional significance. These structures help reduce repulsive forces and facilitate the cell’s motility and phagocytic activity. Microvilli are also present on the cell membrane, aiding in locomotion and adherence to other cells.

- Within the cytoplasm, monocytes contain numerous elongated mitochondria and a Golgi complex. The cytoplasmic granules are small and dense, ranging from 0.05 to 0.2 µm in diameter, and are surrounded by a limiting membrane.

- Monocytes are classified as agranulocytes since they lack visible granules, although they may occasionally display some azurophil granules or vacuoles. They have an amoeboid appearance and comprise 2% to 10% of all leukocytes in the human body. Their large size and unique structural features contribute to their functional roles in the immune system.

Subsets/Types of Monocytes

- In humans, monocytes can be further categorized into different subsets based on the expression of specific cell surface markers. The two main subsets are defined by the expression of CD14 and CD16, which are molecules involved in immune responses.

- The first subset is known as CD14highCD16- or CD14+ monocytes. These monocytes are larger in size, with a diameter of approximately 18 µm, and make up the majority, around 80-90%, of the total circulating monocytes. They express high levels of CD14, which is a component of the lipopolysaccharide receptor complex involved in recognizing bacterial components. CD14+ monocytes also exhibit distinct chemokines, immunoglobulins, adhesion proteins, and scavenger receptors.

- The second subset is referred to as CD16highCD14- or CD16+ monocytes. These monocytes are smaller, with a diameter of around 16 µm, and constitute approximately 10% of the total circulating monocytes in humans. They express high levels of CD16, which is the FcγRIII immunoglobulin receptor. CD16+ monocytes are often associated with a proinflammatory phenotype, producing high levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and lower levels of IL-10 in response to Toll-Like Receptor stimulation. This subset is considered to have a proinflammatory function.

- In addition to the CD14highCD16- and CD16highCD14- subsets, there is another smaller subset of monocytes that can be identified by the expression of specific surface molecules. These monocytes are characterized by the expression of CD14, CD16, and CD64, along with high levels of MHC class II molecules. This subset is often referred to as CD14+CD16+CD64+ monocytes or transitional monocytes. They exhibit high phagocytic activity and possess the ability to activate T cells, indicating their role in adaptive immune responses.

- The presence of different subsets of monocytes allows for functional diversity within the monocyte population. Each subset has distinct characteristics and may play specific roles in immune responses and inflammatory processes. The subsets exhibit differences in receptor expression, cytokine production, and interaction with other immune cells, contributing to the overall complexity and effectiveness of the immune system.

How do Monocytes work against pathogens? (Immunity)

Monocytes play a crucial role in the immune response against pathogens through various mechanisms. Here’s how monocytes work to combat pathogens and contribute to immunity:

- Recognition of Pathogens: Monocytes have toll-like receptors (TLRs) on their cell membrane, which can recognize and bind to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) present on invading pathogens. This interaction triggers signaling pathways within the monocytes, initiating their response to the pathogen.

- Migration to Infection Sites: Upon pathogen recognition, monocytes are stimulated to migrate from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood circulation. This migration occurs within 12 to 24 hours after the initial signal. The monocytes then travel through the bloodstream to reach the affected areas where the infection or inflammation is present.

- Adhesion and Diapedesis: To enter the affected tissues, monocytes first need to adhere to the endothelium, the inner lining of blood vessels, at the site of infection. They do so by interacting with specific molecules on the endothelial surface. Once attached, the monocytes undergo a process called diapedesis, where they squeeze through the gaps between endothelial cells to enter the tissues.

- Phagocytosis: Once inside the affected area, monocytes function as phagocytic cells. They engulf and internalize invading microorganisms, foreign materials, as well as dead and damaged cells. This phagocytic activity helps eliminate pathogens and remove cellular debris, contributing to the resolution of infection and tissue repair.

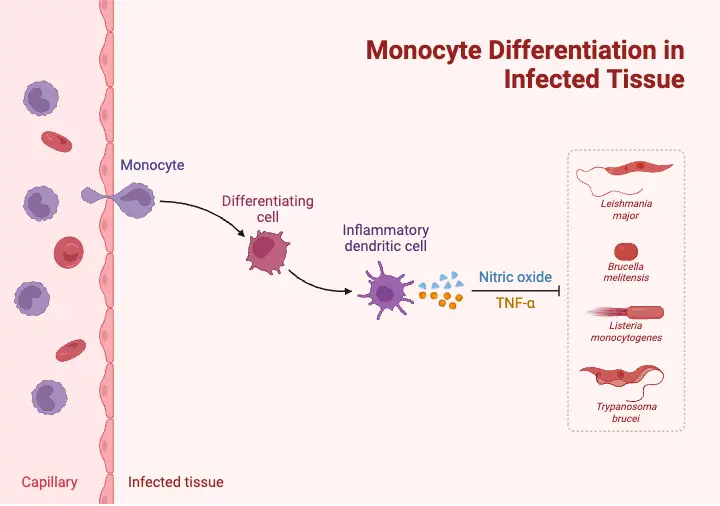

- Differentiation and Cytokine Production: At the site of inflammation, monocytes can undergo further differentiation based on the specific growth factors and cytokines present in the local microenvironment. The differentiation process gives rise to specialized immune cells, such as macrophages or dendritic cells, which possess distinct functions in immune responses.

- Cytokine Release and Inflammation: Monocytes are capable of releasing various cytokines, which are signaling molecules that regulate immune responses. These cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins, and chemokines, have multiple functions. They can recruit other immune cells and compounds into the affected area, enhance the inflammatory response, and help coordinate the overall immune defense against pathogens.

Functions of Monocytes

Monocytes perform a range of important functions within the immune system. Here are some key functions of monocytes:

- Differentiation into Macrophages and Dendritic Cells: Monocytes serve as precursors for populations of macrophages and dendritic cells. They differentiate into these specialized immune cells upon entering tissues. Macrophages play a crucial role in engulfing and eliminating pathogens, debris, and dead cells through phagocytosis. Dendritic cells are antigen-presenting cells that capture, process, and present antigens to activate the adaptive immune response.

- Surveillance and Regulation of Immune Responses: Monocytes constantly patrol the body, monitoring for the presence of pathogens and abnormalities. They contribute to the regulation of immune responses during infection and inflammation by secreting various cytokines and interacting with other immune cells. This helps coordinate and modulate the immune response for optimal defense against pathogens.

- Phagocytosis and Antigen Presentation: Monocytes function as phagocytic cells, actively engulfing and internalizing microorganisms, foreign substances, and dead or damaged cells. This process aids in the elimination of pathogens and cellular debris. Additionally, monocytes can present antigens derived from the engulfed material to activate other immune cells, such as T cells, in the adaptive immune response.

- Cytokine Production and Recruitment: Different subsets of monocytes produce specific cytokines that play critical roles in immune regulation and inflammation. By releasing cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins, and chemokines, monocytes can recruit and attract other immune cells and proteins to the affected sites. This recruitment helps enhance the immune response and coordinate the activities of different immune cells.

- Plasticity and Phenotypic Adaptation: Monocytes display a high degree of plasticity and heterogeneity. They can change their functional phenotypes in response to environmental signals and cues. This adaptability allows monocytes to fulfill diverse roles in different immune contexts, ranging from phagocytosis to cytokine secretion and antigen presentation.

- Activation of T Cells: A specific subset of monocytes known as transitional monocytes plays a role in the activation of T cells, a crucial aspect of adaptive immunity. Transitional monocytes express specific surface markers and are capable of interacting with and activating T cells, thereby initiating specific immune responses against pathogens.

FAQ

What are monocytes?

Monocytes are a type of white blood cell that play a key role in the immune system by helping to fight off infections and other diseases.

What do monocytes look like?

Monocytes are the largest of the white blood cells and have a distinctive kidney-shaped nucleus. They are round or oval in shape and are typically about 12-20 micrometers in diameter.

What is the function of monocytes?

Monocytes are phagocytic cells, which means they are able to engulf and destroy pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses. They also help to activate other immune cells and produce cytokines, which are important for regulating immune responses.

Where are monocytes produced?

Monocytes are produced in the bone marrow, the spongy tissue inside bones that is responsible for the production of blood cells.

How do monocytes differ from other white blood cells?

Monocytes are a type of granulocyte, which means they do not contain granules or vesicles in their cytoplasm like other white blood cells such as neutrophils and eosinophils. Monocytes also have a longer lifespan than other white blood cells.

What is a monocyte count?

A monocyte count is a blood test that measures the number of monocytes in the blood. This test is often performed as part of a complete blood count (CBC).

What does a high monocyte count indicate?

A high monocyte count can indicate an infection or inflammation in the body. It can also be a sign of a blood disorder, such as leukemia.

What does a low monocyte count indicate?

A low monocyte count can indicate a weakened immune system or a bone marrow disorder.

How are monocytes produced in the body?

Monocytes are produced in the bone marrow from stem cells. They then travel through the bloodstream to various tissues and organs where they mature into macrophages or dendritic cells.

What are some common monocyte disorders?

Some common monocyte disorders include monocytosis (high monocyte count), monocytopenia (low monocyte count), and monocytic leukemia (cancer of the monocytes).

Can monocyte levels be influenced by lifestyle choices?

Yes, lifestyle choices such as diet and exercise can affect monocyte levels. For example, a diet high in antioxidants can help to reduce inflammation and lower monocyte levels.

How are monocyte disorders treated?

The treatment for a monocyte disorder depends on the underlying cause. In some cases, antibiotics or antiviral medications may be prescribed to treat an infection. In other cases, chemotherapy or bone marrow transplants may be necessary to treat leukemia.

References

- Van Furth, R., & Beekhuizen, H. (1998). Monocytes. Encyclopedia of Immunology, 1750–1754. doi:10.1006/rwei.1999.0443

- Espinoza VE, Emmady PD. Histology, Monocytes. [Updated 2022 Apr 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557618/

- https://www.biologyonline.com/dictionary/monocyte

- https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1581§ionid=108066052#1121096172

- https://www.lalpathlabs.com/blog/what-are-monocytes-definition-function-blood-test/