Chlamydia is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis which is a Gram-negative bacterium, and it is the organism that behave as an obligate intracellular parasite because it cannot produce its own metabolic energy. It is the process where the bacterium must survive and replicate inside the eukaryotic host cell, and this organism shows a biphasic developmental cycle in which the elementary body (EB) act as the infectious form and the reticulate body (RB) act as the non-infectious replicative form.

The infection is usually asymptomatic in many individuals and this is referred to as a silent type of infection because most women and men do not show early symptoms, allowing the pathogen to persist for long period. It is the major cause of sexually transmitted infection and some strains also cause trachoma which is responsible for infection-related blindness.

When symptoms appear, these are seen in the urogenital tract, rectum, or throat, and conditions like urethritis or cervicitis is commonly observed. Some of the important serovars (L1–L3) produce lymphogranuloma venereum in which the lymph nodes is affected. If the infection is not treated then complications like pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy and epididymitis in men is seen. It is the process that can be cured by antibiotics like doxycycline or azithromycin when taken properly.

Requirements

- A fluorescence microscope is required because Chlamydia does not retain the Gram stain. It is the method that uses an epifluorescence microscope with proper filters (FITC type) and high-power lenses (×600–×1000) with non-fluorescing immersion oil.

- Fluorescein-labelled monoclonal antibodies is used in Direct Fluorescent Antibody techniques where MOMP or LPS components are detected and the stained elementary bodies appear as bright apple-green discs.

- Giemsa stain is used in light microscopy to observe intracytoplasmic inclusions where the elementary bodies stain purple and the reticulate bodies stain blue.

- Iodine stain (Lugol’s iodine) is used to detect the glycogen-rich inclusions of C. trachomatis which stain dark brown and this reaction is not shown by other Chlamydia species.

- Pap stain can show cytopathic changes of infected cells where the cytoplasm shows fine vacuolation giving a moth-eaten appearance.

- Transmission electron microscope or cryo-electron tomography is required to observe ultrastructure where the elementary body is seen with a thick membrane and dense nucleoid.

- Columnar or cuboidal epithelial cells is required in the specimen because the organism is intracellular and discharge alone does not give proper material.

- Swabs with plastic or wire shafts and rayon or dacron tips is used because cotton or wooden shafts can inhibit the organism.

- The specimen slide is prepared by rolling the swab on the slide surface, followed by air drying and fixation with methanol or acetone before staining.

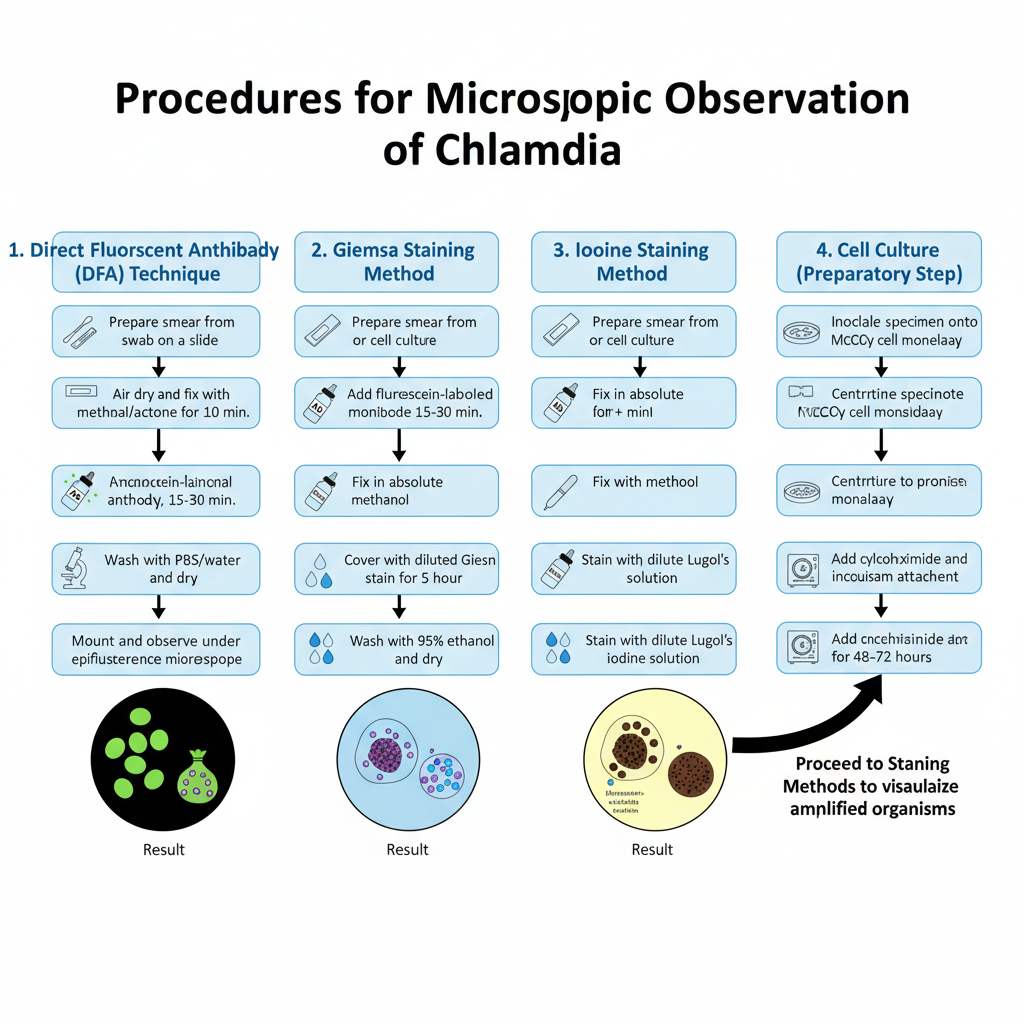

Procedure to Observe Chlamydia Under Microscope

1. Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) Technique

The organism is not detected by ordinary Gram staining, so this method is used for observing the antigenic structures.

- Collect the smear from endocervical, urethral or conjunctival swab and the swab is rolled on the slide to make a thin film.

- The smear is air dried completely and it is fixed with methanol or acetone for about 10 minutes.

- The fluorescein–labelled monoclonal antibody reagent is now added over the fixed smear and kept in a moist chamber for 15–30 minutes.

- The slide is washed with PBS or distilled water and excess stain is removed and then it is dried.

- Mounting fluid is added and a coverslip is placed. The slide is observed under an epifluorescence microscope.

- The elementary bodies is seen as bright apple–green disc like structures and intracellular inclusions appear as green sacs in the cytoplasm.

2. Giemsa Staining Method

This staining is used for demonstrating the inclusion bodies and the two developmental forms.

- A smear is prepared from conjunctival scrapings or cell culture and it is air dried.

- The slide is fixed in absolute methanol for at least 5 minutes and dried.

- The smear is covered with diluted Giemsa stain for nearly one hour.

- Excess stain is removed by quick washing in 95% ethanol and the slide is dried.

- Elementary bodies stain purple while the reticulate bodies stain blue and the compact inclusion mass is seen dark purple near the nucleus.

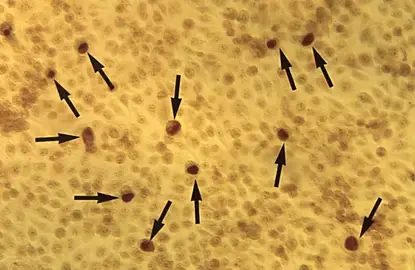

3. Iodine Staining Method

It is the process used to detect glycogen containing inclusions, which is characteristic of C. trachomatis.

- The smear or culture monolayer is prepared and fixed with methanol.

- A dilute Lugol’s iodine solution is added for staining.

- The inclusions is stained dark brown because of glycogen and the host cell cytoplasm shows faint yellow colour.

4. Cell Culture (McCoy Cell Technique)

It is the method used to increase the number of organisms before staining.

- The specimen is inoculated on a confluent monolayer of McCoy or HeLa 229 cells and centrifuged so the organisms attach to the cells.

- Cycloheximide is added in the medium for inhibiting host cell division and the culture is incubated for 48–72 hours.

- After incubation the cell sheet is fixed and stained by immunofluorescence, Giemsa or iodine stain to see the intracytoplasmic inclusions.

Observation and Result of Chlamydia Under Microscope

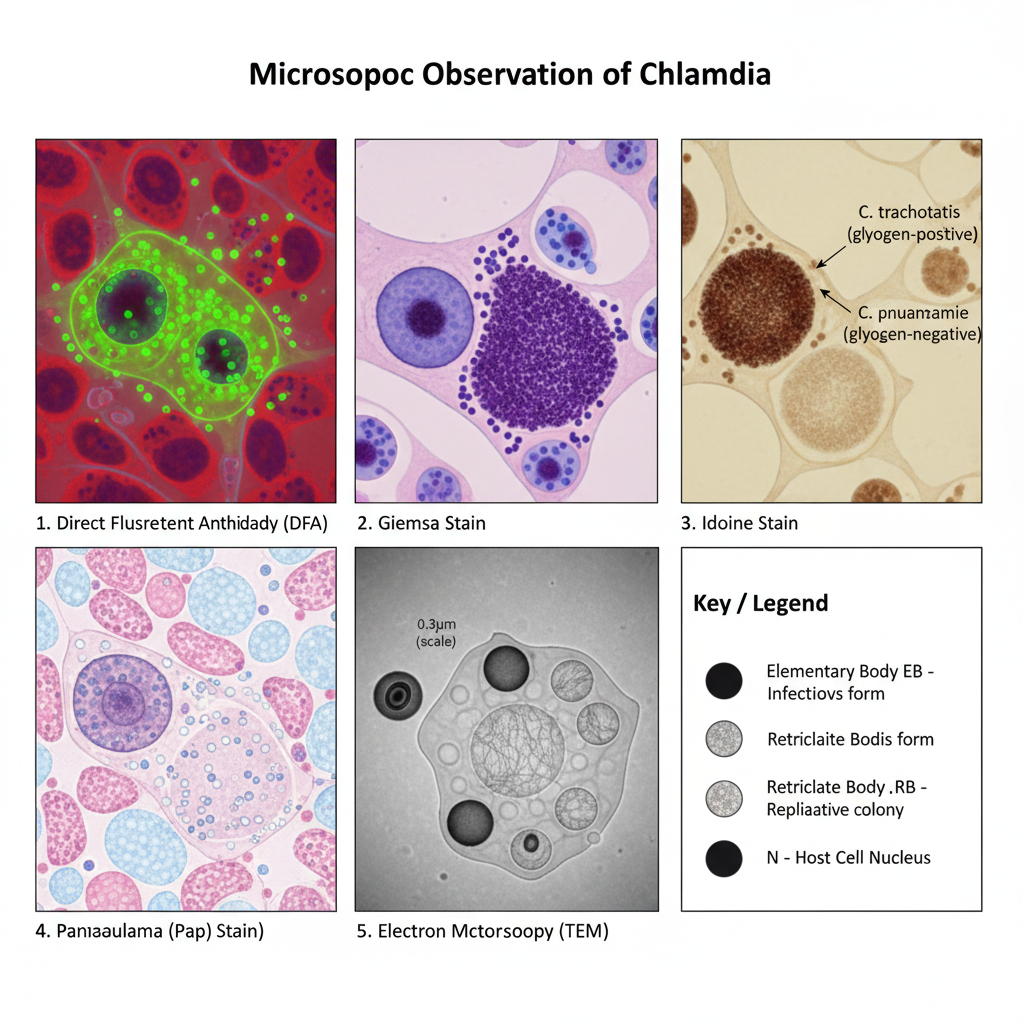

1. Observation in DFA (Fluorescent Antibody Method)

- The elementary bodies is seen as very small bright apple–green discs having smooth outline and they appear over a red background of host cells.

- The reticulate bodies is larger in size and these structures sometimes show a dark central area with a green halo.

- The inclusions of the organism appear as bright green sacs inside the cytoplasm of infected cell.

2. Observation in Giemsa Stain

- Elementary bodies stain purple and appear as small dot like bodies.

- Reticulate bodies stain blue and appear comparatively larger.

- The mature inclusion is seen as a dark purple compact mass and it is usually present near the nucleus.

3. Observation in Iodine Stain

- In C. trachomatis the inclusions contain glycogen so these inclusions stain dark brown.

- In species like C. psittaci and C. pneumoniae the inclusions do not take iodine stain and appear pale yellow or colourless.

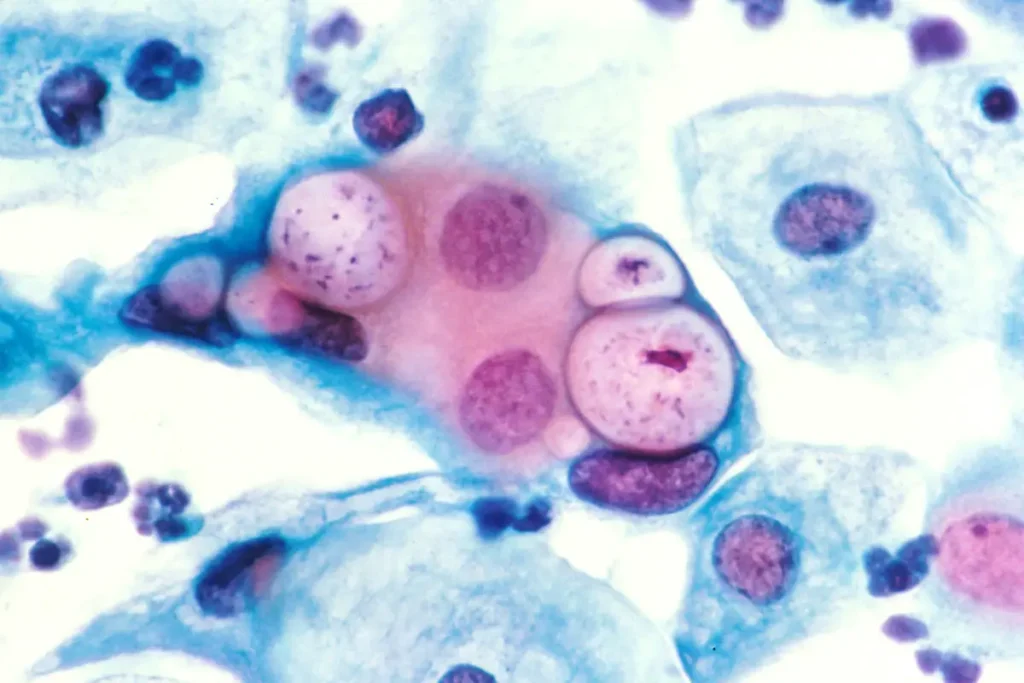

4. Observation in Pap Stain

- The infected epithelial cells show fine vacuolation of cytoplasm and the cell looks like moth–eaten appearance.

- Some basophilic or acidophilic intracytoplasmic bodies may be present but these structures is not easy to differentiate from other debris.

5. Observation in Electron Microscopy

- The elementary bodies appear as electron dense spherical structures (0.2–0.4 µm) with a thick rigid membrane.

- The reticulate bodies appear bigger (0.6–1.0 µm) and the membrane is thinner with a diffuse fibrillar nucleic acid material.

- In the EB a tubular inner membrane invagination is present and it lies opposite to the Type III secretion structure.

- AbdelRahman, Y. M., & Belland, R. J. (2005). The chlamydial developmental cycle. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 29(5), 949–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.002

- Basicmedical Key. (2016, June 12). Chlamydia spp. [Excerpt from Jawetz Melnick & Adelberg’s Medical Microbiology 27e].

- Becker, Y. (1996). Chlamydia. In S. Baron (Ed.), Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8091/

- Carder, C., Mercey, D., & Benn, P. (2006). Chlamydia trachomatis. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82(Suppl 4), iv10–iv12. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2006.023069

- Chernesky, M. A. (2005). The laboratory diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology, 16(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1155/2005/359046

- Chiarelli, T. J., Grieshaber, N. A., Omsland, A., Remien, C. H., & Grieshaber, S. S. (2020). Single-inclusion kinetics of Chlamydia trachomatis development. mSystems, 5(5), e00689-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00689-20

- Forster, G. E., Cookey, I., Munday, P. E., Richman, P. I., Jha, R., Coleman, D., Thomas, B. J., Hawkins, D. A., Evans, R. T., & Taylor-Robinson, D. (1985). Investigation into the value of Papanicolaou stained cervical smears for the diagnosis of chlamydial cervical infection. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 38(4), 399–402. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.38.4.399

- Ghuysen, J. M., & Goffin, C. (1999). Lack of cell wall peptidoglycan versus penicillin sensitivity: New insights into the chlamydial anomaly. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 43(10), 2339–2344. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.43.10.2339

- Gupta, P. K., Shurbaji, M. S., Mintor, L. J., Ermatinger, S. V., Myers, J., & Quinn, T. C. (1988). Cytopathologic detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in vaginopancervical (fast) smears. Diagnostic Cytopathology, 4(3), 224–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.2840040309

- Gurina, T. S., & Simms, L. (2023, May 1). Histology, Staining. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557663/

- Guseva, N. V., Dessus-Babus, S., Moore, C. G., Whittimore, J. D., & Wyrick, P. B. (2007). Differences in Chlamydia trachomatis Serovar E growth rate in polarized endometrial and endocervical epithelial cells grown in three-dimensional culture. Infection and Immunity, 75(2), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01517-06

- Huang, Z., Chen, M., Li, K., Dong, X., Han, J., & Zhang, Q. (2009). Cryo-electron tomography of Chlamydia trachomatis gives a clue to the mechanism of outer membrane changes. Journal of Electron Microscopy, 59(3), 237–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmicro/dfp057

- Jacquier, N., Viollier, P. H., & Greub, G. (2015). The role of peptidoglycan in chlamydial cell division: Towards resolving the chlamydial anomaly. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 39(2), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuv001

- Kalman, S., Mitchell, W., Marathe, R., Lammel, C., Fan, J., Hyman, R. W., Olinger, L., Grimwood, J., Davis, R. W., & Stephens, R. S. (1999). Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Nature Genetics, 21(4), 385–389. https://doi.org/10.1038/7716

- Mohseni, M., Sung, S., & Takov, V. (2023, August 8). Chlamydia. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537286/

- Mokobi, F. (2022, September 25). Giemsa Stain- Principle, Procedure, Results, Interpretation. Microbe Notes.

- Nans, A., Saibil, H. R., & Hayward, R. D. (2014). Pathogen–host reorganization during Chlamydia invasion revealed by cryo-electron tomography. Cellular Microbiology, 16(10), 1457–1472. https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12310

- Oba, Y. (2025, March 3). Chlamydial Pneumonias. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/297351-overview

- Oxoid Limited. (2020, July). IMAGEN Chlamydia [Instructions for Use].

- Papp, J. R., Schachter, J., Gaydos, C. A., & Van Der Pol, B. (2014). Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae — 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 63(RR-02), 1–19.

- Rodrigues, R., Silva, A. R., Sousa, C., & Vale, N. (2024). Addressing challenges in Chlamydia trachomatis detection: A comparative review of diagnostic methods. Medicina, 60(8), 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081236

- Santalucía, M., & Farinati, A. (2015). Chlamydia trachomatis infections and their impact in the adolescent population. DST – Jornal Brasileiro de Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis, 27(3-4), 112-125.

- Superdrug Online Doctor. (n.d.). What does Chlamydia look like? Retrieved from https://onlinedoctor.superdrug.com/what-chlamydia-looks-like.html

- Chlamydia trachomatis. (2025). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chlamydia_trachomatis&oldid=1325103752