Varicella zoster virus

- Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), also referred to as human herpesvirus 3 (HHV-3, HHV3) or Human alphaherpesvirus 3 (taxonomically), is one of nine known human herpes viruses.

- It causes chickenpox (varicella) in children and early adults, and zoster (herpes zoster) in adults but not children. VZV infections are only found in humans. A few hours of virus survival in external environments is possible.

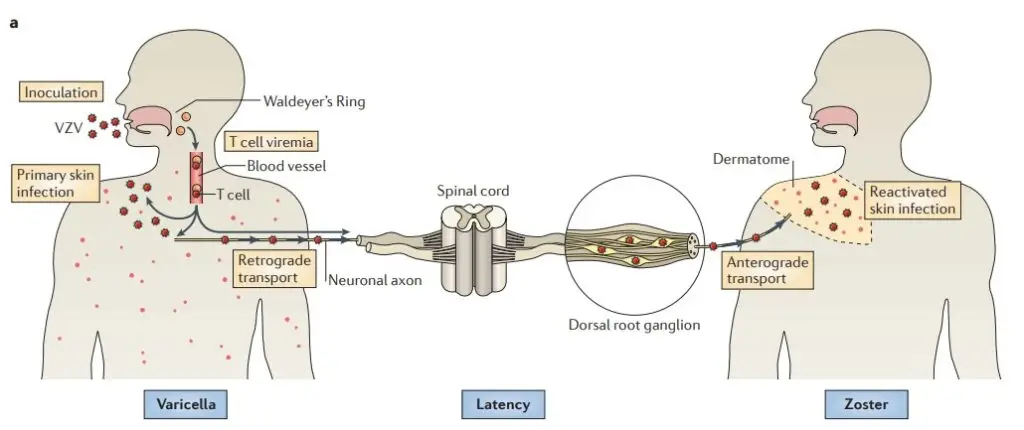

- The VZV virus multiplies in the pharynx, causing an array of symptoms. Similar to herpes simplex viruses, VZV (chickenpox) remains dormant in neurons, including cranial nerve ganglia, dorsal root ganglia, and autonomic ganglia, after primary infection.

- VZV can reactivate to induce shingles many years after the initial chickenpox infection has been resolved.

- Varicella is caused by the herpesvirus varicella-zoster (VZV), which has a universal distribution. It establishes latency following primary infection, a characteristic uncommon among herpes viruses.

- Inhalation of infected aerosolized particulates is required. This virus is highly infectious and can swiftly spread. Initial infection occurs in the upper airway mucosa.

- After 2-6 days, the virus penetrates the circulation, and 10-12 days later, another bout of viremia occurs. The characteristic vesicle appears at this time.

- Antibodies IgA, IgM, and IgG are produced, but only IgG antibodies confer lifelong immunity. Varicella localized to sensory nerves following the primary infection and may reactivate in the future to cause shingles.

Varicella, also known as chickenpox, is an infectious disease caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). The virus causes chickenpox (typically primary infection in non-immune hosts) and herpes zoster or shingles (after reactivation of latent infection). Chickenpox causes a rash consisting of small, itchy lesions that scab over. It begins on the chest, back, and face before spreading. It is typically accompanied by fever, fatigue, pharyngitis, and migraines that last between five and seven days. pneumonia, cerebral inflammation, and bacterial skin infections are examples of complications. Adults are more severely affected than infants. Ten to twenty-one days after exposure, symptoms appear, but the average incubation period is about two weeks.

Chickenpox is a ubiquitous, airborne disease that is transmitted through coughing, sneezing, and contact with vesicles. It may begin to spread one to two days prior to the rash’s appearance and continue until all lesions crust over. Patients with zoster may transmit varicella to susceptible individuals through blister contact. The disease is diagnosed on the basis of presenting symptoms and confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of lesion fluid or scabs. To determine if immunity is present, antibody tests can be administered. Although varicella reinfections are possible, they are typically asymptomatic and much milder than the initial infection.

The introduction of the varicella vaccine in 1995 has significantly reduced the number of cases and complications. It prevents between 70 and 90 percent of infections and 95 percent of severe diseases. It is recommended that minors be routinely immunised. Immunisation administered within three days of exposure may still enhance children’s health outcomes.

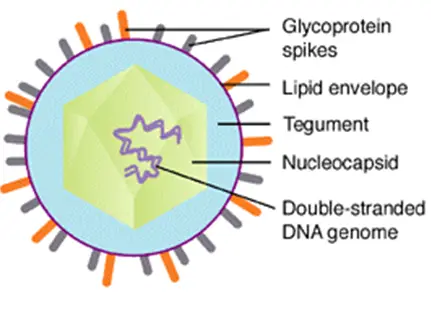

Structure of Varicella Zoster Virus

- VZV is closely related to herpes simplex viruses (HSV) and their genomes are highly similar. The known envelope glycoproteins (gB, gC, gE, gH, gI, gK, and gL) correspond to those of HSV; however, the HSV gD protein does not have a known counterpart.

- VZV is also incapable of producing the LAT (latency-associated transcripts) that play a crucial role in establishing HSV (herpes simplex virus) latency.

- VZV virions are spherical and have a diameter of 180–200 nm. Their lipid envelope encloses a 100 nm nucleocapsid consisting of 162 hexameric and pentameric capsomeres arranged in an icosahedral structure. Its DNA is a 125,000-nt-long, single, linear, double-stranded molecule.

- The capsid is surrounded by loosely associated proteins known as the tegument; many of these proteins play essential roles in initiating the process of viral reproduction in an infected cell.

- The tegument is then enveloped by a lipid envelope studded with approximately 8 nm-long glycoproteins that are displayed on the exterior of the virion.

Summery: VZV virions are spherical and have a diameter of 180–200 nm. Their lipid envelope contains the icosahedral nucleocapsid structure. Its DNA is a double-stranded, linear molecule with approximately 125,000 base pairs (bp) and at least 71 open reading frames (ORFs). Approximately two-thirds of VZV ORFs are required for in vitro replication, including eight glycoproteins (gB, gC, gE, gH, gI, gK, gL, gN) involved in DNA replication and other functions. The glycoproteins gB (gp II), gE (gp I), and gH (gp III) can stimulate the production of neutralizing antibodies in the body. gE is the major surface-distributed protein of the envelope and has epitopes associated with the virus. gB and gH contain less antigen than gE, but they can also be used to produce subunit vaccines.

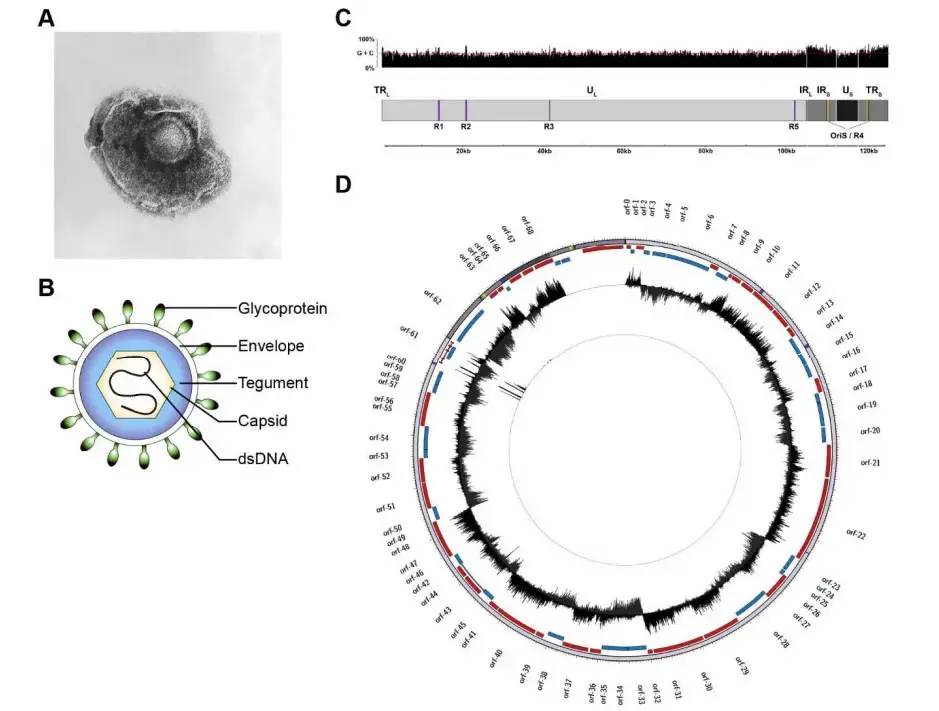

Genome of Varicella Zoster Virus

- The VZV dsDNA genome is approximately 125,611 base pairs (kbp) in length, has a G+C content of 46%, and consists of two unique segments, unique long (UL) and unique short (US), which are flanked by inverted terminal repeat (TR) and internal repeat (IR) structures with high G+C content (68% for the TRL/IRL and 59% for the IRS/TRS).

- The extremely brief TRL and IRL sequences (~88 bp) flank the UL region, while the lengthy IRS and TRS sequences (7,319 bp) flank the US region. In general, the composite structure permits two isomeric configurations distinguished solely by the orientation of the US region.

- A unique DNA sequence at the extreme 5′ end of the UL region is required for viral DNA cleavage during packaging, which explains the lack of structural isoforms with inverted UL regions.

- One of the five genomic regions containing tandem direct reiterations (R1, R2, R3, R4, and R5) of brief repeat sequences is the IRS/TRS. Except for R5, all are G+C-rich, and all exhibit length and structural polymorphisms that vary between strains.

- Three of these reiterative regions (R1, R2, and R3) are located within the coding region of VZV genes (open reading frame (ORF) 11, ORF14, and ORF20, respectively) and may therefore influence protein function.

Epidemiology of Varicella Zoster Virus

- Varicella occurs in all nations and is responsible for approximately 7,000 fatalities annually. It is a prevalent childhood disease in temperate countries, with the majority of cases occurring during the winter and spring.

- It accounts for more than 9000 hospitalizations annually in the United States. It is most prevalent in children aged 4 to 10 years.

- There is a 90% infection rate for varicella. Secondary cases among domestic contacts are typically more severe than primary cases.

- In the tropics, varicella is more prevalent among older individuals and may produce more severe disease. Adults will develop deep pockmarks and more noticeable wounds.

Transmission of Varicella Zoster Virus

- Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) is primarily spread through respiratory droplets that are expelled when an infected person coughs or sneezes. These droplets can be inhaled by people nearby, leading to infection.

- Another way that VZV can be transmitted is through contact with fluid from the rash that develops during the illness. This can occur when someone with the virus touches or scratches their rash and then touches another person or surface, or when the fluid from the rash comes into contact with an open wound on another person.

- It is also possible to contract VZV by touching a surface contaminated with the virus and then touching your mouth, nose, or eyes.

- VZV can be highly contagious, and people with the virus can spread it to others before they even realize they are sick. The best way to prevent the transmission of VZV is to get vaccinated against the virus.

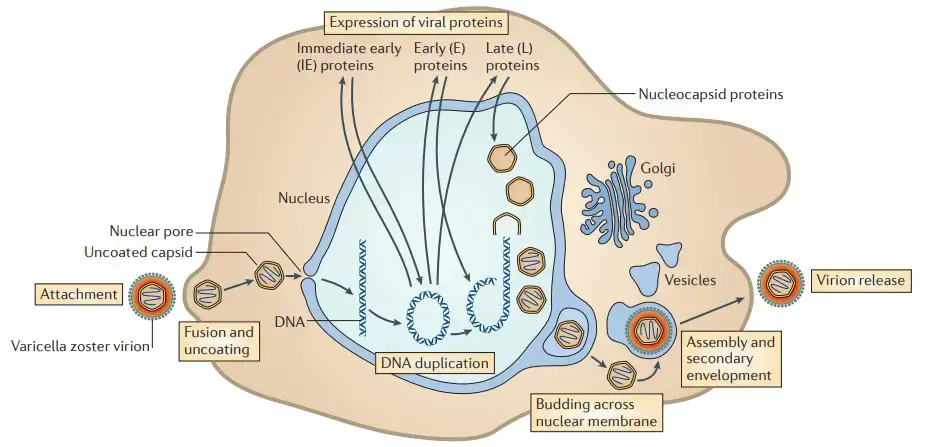

Replication and Life cycle of Varicella Zoster Virus

Life cycle

The human host is infected by VZV when virus particles reach mucosal epithelial entry sites. VZV obtains access to T cells after spreading to tonsils and other regional lymphoid tissues following local replication. Infected T cells then transport the virus to sites of replication on the skin. After transport to neuronal nuclei along neuronal axons or via viremia, VZV establishes latency in sensory ganglia. Reactivation from latency permits a second phase of replication in skin, which typically results in lesions in the dermatome innervated by the afflicted sensory ganglion.

Replication

- Attachment of enveloped VZV particles to cell membranes, fusion, and release of tegument proteins.

- Uncoated capsids attach to nuclear apertures, where genomic DNA is injected and circularizes within the nucleus.

- Based on the documented events of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) replication, the immediate-early genes are expressed first, followed by the early and late genes.

- Assembled nucleocapsids bundle newly synthesized genomic DNA, migrate to the inner nuclear membrane, and proliferate across the nuclear membrane.

- Virion glycoproteins mature in the trans-Golgi region, while tegument proteins assemble in vesicles; capsids undergo secondary envelopment and are transported to cell surfaces, where newly assembled virus particles are released.

Pathophysiology

Exposure results in the production of immunoglobulin G, M, and A by the host. IgG antibodies are immortal and provide immunity. The importance of cell-mediated immune responses in limiting the duration of primary varicella infection. Varicella is believed to disseminate to mucosal and epidermal lesions and local sensory nerves after the initial infection. The virus then becomes dormant within the dorsal ganglion cells of the sensory nerves. The immune system controls the virus, but reactivation may occur later in life, resulting in the clinically distinct syndromes of herpes zoster (shingles), postherpetic neuralgia, and occasionally Ramsay Hunt syndrome type II. Varicella zoster can cause a stroke by damaging the arteries in the neck and cranium.

Clinical Presentation of Varicella Zoster Virus

- Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection can cause two different clinical presentations of the disease: varicella (also known as chickenpox) and herpes zoster (also known as shingles).

- Varicella is the primary infection caused by VZV and typically affects children. It is characterized by a generalized rash that starts on the face, scalp, and trunk before spreading to other parts of the body. The rash consists of fluid-filled blisters that eventually scab over and heal. Varicella is highly contagious and can be transmitted through respiratory droplets or contact with fluid from the rash.

- Herpes zoster, on the other hand, is a reactivation of the VZV infection that typically occurs in adults. It presents as a painful, unilateral rash in a specific area of the body, usually on the chest or abdomen. The rash consists of fluid-filled blisters that eventually scab over and heal. Herpes zoster is not contagious, but the virus can be transmitted to people who have not previously been infected with VZV and can cause them to develop varicella.

- Both varicella and herpes zoster are caused by the same virus, but they have distinct clinical presentations and are caused by different phases of the infection. Vaccination against VZV is the most effective way to prevent both varicella and herpes zoster.

Laboratory diagnosis of Varicella Zoster Virus

The laboratory diagnosis of Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) infection can be accomplished through various methods:

- Viral Culture: The virus can be grown in cell cultures and the presence of the virus can be confirmed by examining the cultured cells for characteristic cytopathic effects (CPEs).

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): PCR is a molecular diagnostic method that can detect viral DNA in clinical samples such as blood, swabs from lesions, or cerebrospinal fluid. PCR is a highly sensitive and specific method for detecting VZV.

- Serology: Serologic tests can detect the presence of antibodies against VZV in blood samples. Antibody detection can be done by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), complement fixation, or fluorescent antibody tests.

- Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA): This technique involves staining of cells in clinical specimens with fluorescent antibodies that specifically bind to VZV antigens.

- Microscopy Methods: Direct microscopy can be performed on clinical specimens such as vesicle fluid, skin scrapings, or respiratory secretions, to observe the presence of characteristic multinucleated giant cells. These cells have several nuclei and are often seen in VZV infections.

It is important to note that laboratory diagnosis is not routinely required for the diagnosis of VZV infection, as the typical clinical presentation of the disease is often sufficient for diagnosis. However, laboratory testing can be helpful in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, or when the disease occurs in immunocompromised individuals.

Treatment of Varicella Zoster Virus

The treatment consists of symptomatic relief. As a precaution, infected individuals are typically required to remain at home while they are contagious. Maintaining short fingernails and donning gloves may prevent scratching and reduce the risk of secondary infections.

Topical calamine lotion may relieve pruritus. Daily cleansing with tepid water will aid in the prevention of secondary bacterial infection. The use of acetaminophen to diminish fever is permitted. Aspirin may cause Reye syndrome, so avoid taking it. Those at risk of developing complications and who have had significant exposure may be administered intramuscular varicella-zoster immune globulin, a preparation containing high titers of antibodies to the varicella-zoster virus, in order to prevent the disease.

- If administered within 24 hours of the rash’s onset, acyclovir reduces symptoms by one day in children, but has no effect on complication rates and is not recommended for individuals with a healthy immune system.

- Treatment with antiviral medications (acyclovir or valacyclovir) is advised if it can be initiated within 24 to 48 hours of rash onset in adults, whose infections tend to be more severe. Supportive care, such as increasing fluid intake and administering antipyretics and antihistamines, is an essential component of treatment. Adults, including expectant women, are typically prescribed antivirals because they are more prone to complications. Antivirals administered intravenously are indicated for immunocompromised patients, for whom oral therapy is the favored treatment.

Varicella-zoster immunoglobulin is used to treat immunocompromised patients. Moreover, an attenuated live vaccine has been available since 1995. There is a high level of seroconversion following vaccination, which is long-lasting. Rarely do adverse reactions to the vaccine occur.

Prevention and control of Varicella Zoster Virus

Prevention and control of Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) infection can be achieved through various measures:

- Vaccination: Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing VZV infection. Two doses of the varicella vaccine are recommended for children, adolescents, and adults who have not had chickenpox. The herpes zoster vaccine is also recommended for adults over 50 years of age.

- Personal hygiene: Good personal hygiene, including frequent hand washing, is important in preventing the spread of VZV.

- Isolation: Individuals with varicella should be isolated from others to prevent transmission of the virus. They should avoid school or work until all blisters have scabbed over.

- Post-exposure prophylaxis: Individuals who are exposed to VZV and have not had chickenpox or been vaccinated should receive the varicella vaccine within 3-5 days of exposure.

- Antiviral therapy: Antiviral therapy, such as acyclovir, can be used in individuals who are at high risk of severe VZV infection, such as immunocompromised individuals.

- Management of outbreaks: In outbreak settings, prompt identification of cases and implementation of control measures such as isolation and vaccination can help prevent the spread of VZV.

It is important to note that VZV can be highly contagious, and individuals who are not immune to the virus should take appropriate precautions to prevent infection. Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing VZV infection, and all individuals who are eligible for vaccination should receive it to help prevent the spread of the virus.

FAQ

What is Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV)?

Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) is a highly contagious virus that causes two distinct forms of disease: chickenpox (varicella) and shingles (herpes zoster).

How is VZV transmitted?

VZV is primarily transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual’s respiratory secretions or the fluid from their skin lesions.

Who is at risk for VZV infection?

Anyone who has not had chickenpox or been vaccinated against VZV is at risk for infection.

What are the symptoms of chickenpox?

The symptoms of chickenpox include fever, headache, fatigue, and a rash that develops into itchy, fluid-filled blisters that scab over.

What are the symptoms of shingles?

The symptoms of shingles include a painful, blistering rash that typically appears on one side of the body and may be accompanied by fever, headache, and fatigue.

How is VZV diagnosed?

VZV can be diagnosed through laboratory testing, including PCR, viral culture, and serology.

Is there a cure for VZV infection?

There is no cure for VZV infection, but antiviral medications can be used to reduce the severity and duration of symptoms.

Can VZV be prevented?

Yes, VZV infection can be prevented through vaccination, good personal hygiene, and isolation of infected individuals.

Who should receive the VZV vaccine?

The VZV vaccine is recommended for children, adolescents, and adults who have not had chickenpox or been vaccinated against VZV.

What are the potential complications of VZV infection?

Complications of VZV infection can include bacterial skin infections, pneumonia, encephalitis, and post-herpetic neuralgia.

References

- Ayoade F, Kumar S. Varicella Zoster (Chickenpox) [Updated 2022 Oct 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448191/

- Arvin AM. Varicella-zoster virus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996 Jul;9(3):361-81. doi: 10.1128/CMR.9.3.361. PMID: 8809466; PMCID: PMC172899.

- Mueller NH, Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA. Varicella zoster virus infection: clinical features, molecular pathogenesis of disease, and latency. Neurol Clin. 2008 Aug;26(3):675-97, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.03.011. PMID: 18657721; PMCID: PMC2754837.

- Zerboni, Leigh & Sen, Nandini & Oliver, Stefan & Arvin, Ann. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of varicella zoster virus pathogenesis. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 12. 10.1038/nrmicro3215.

- Heinz J, Kennedy PGE, Mogensen TH. The Role of Autophagy in Varicella Zoster Virus Infection. Viruses. 2021; 13(6):1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13061053

- Zerboni L, Sen N, Oliver SL, Arvin AM. Molecular mechanisms of varicella zoster virus pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014 Mar;12(3):197-210. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3215. Epub 2014 Feb 10. PMID: 24509782; PMCID: PMC4066823.

- Depledge, Daniel & Sadaoka, Tomohiko & Ouwendijk, Werner J.D.. (2018). Molecular Aspects of Varicella-Zoster Virus Latency. 10.20944/preprints201806.0036.v1.

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009 Dec;9 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S108-15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02901.x. PMID: 20070670; PMCID: PMC2919834.

- https://health.mo.gov/living/healthcondiseases/communicable/chickenpox.php

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/231927-overview

- https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/index.html

- https://viralzone.expasy.org/15