Rotavirus is a family of double-stranded RNA viruses belonging to the genus Reoviridae. Rotaviruses are the leading cause of diarrhea in neonates and young children. By the age of five, nearly every child in the world has been infected with rotavirus at least once.Immunity develops with each infection, reducing the severity of subsequent infections. Rarely are adults affected. There are nine species in the genus, designated by the letters A through J. Rotavirus A, the most prevalent species, is responsible for over ninety percent of rotavirus infections in humans.

The virus is transmitted through a feces-to-mouth route. It infects and damages the cells that line the small intestine, causing gastroenteritis (commonly referred to as “stomach flu” despite being unrelated to influenza). Although rotavirus was discovered in 1973 by Ruth Bishop and her colleagues using electron micrograph images and accounts for approximately one-third of hospitalizations for severe diarrhoea in infants and children, its significance has been historically underestimated by the public health community, particularly in developing nations. In addition to affecting human health, rotavirus infects other animals and is a livestock pathogen.

Rotaviral enteritis is typically a manageable childhood illness, but in 2019 rotavirus caused an estimated 151,714 diarrhea-related fatalities among children under 5 years old.Before the initiation of the rotavirus vaccination program in the 2000s, rotavirus was responsible for approximately 2.7 million cases of severe gastroenteritis in children, nearly 60,000 hospitalizations, and approximately 37 fatalities annually in the United States.Following the introduction of rotavirus vaccine in the United States, hospitalization rates have decreased significantly. To combat rotavirus, public health campaigns emphasize oral rehydration therapy for infected children and vaccination to prevent the disease. The incidence and severity of rotavirus infections have decreased significantly in nations where rotavirus vaccine is routinely administered to children.

Classification of rotavirus

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Duplornaviricota |

| Class: | Resentoviricetes |

| Order: | Reovirales |

| Family: | Reoviridae |

| Subfamily: | Sedoreovirinae |

| Genus: | Rotavirus |

Types of rotavirus

- There are nine rotavirus species, designated A, B, C, D, F, G, H, I, and J.

- Rotavirus A is the predominant species that infects humans. A–I species cause disease in other animals,including species H in swine, D, F, and G in birds, I in cats, and J in bats.

- Within the Rotavirus A species, there are distinct strains known as serotypes. As with the influenza virus, a dual classification system is utilized based on two surface proteins.

- The glycoprotein VP7 and the protease-sensitive protein VP4 define the G and P serotypes, respectively. Due to the fact that the two alleles that determine G-types and P-types can be passed on to progeny viruses independently, various combinations are possible.

- A system for genotyping the entire genome of Rotavirus A has been developed and has been used to determine the origin of atypical strains. The incidence of the various G- and P-types differs between and within countries and years.

- There are at least 36 G types and 51 P types, but only a few combinations of G and P types predominate in human infections. These are G1P[8, G2P[4, G3P[8, G4P[8, G9P[8, and G12P[8, respectively.

Epidemiology of rotavirus

- Rotaviruses are widespread, and the majority of children are infected by the age of five. The incidence of infection is comparable throughout the world, but catastrophic infections are more prevalent in low-income regions.

- This is likely a result of inadequate healthcare facilities, rising malnutrition rates, and lack of access to clean, hygienic hydration therapies. Rotavirus is traditionally considered a winter illness, particularly in temperate regions of the world.

- In tropical climates, seasonality is less pronounced, and infections tend to occur throughout the year. The frequency of rotavirus infections in temperate climates may also be related to precipitation levels, according to some research.

- According to a study conducted in Washington, D.C., there was a 45% increase in rotavirus hospitalizations in months with minimal precipitation compared to months with higher precipitation. This suggests that rotavirus transmission is more prevalent in low-humidity environments, such as winter and arid months throughout the year.

- Currently, ten distinct species of rotavirus are classified (A-J). Rotaviruses of Species A are the leading cause of childhood infections, with Species B and C causing a lesser but still significant proportion of infections worldwide. Globally circulating genotypes of species A rotaviruses have been observed to vary geographically.

- Since the introduction of vaccines against rotavirus, the epidemiology of rotavirus disease has changed dramatically. Prior to the development of vaccines, rotavirus infection was most prevalent in children younger than 5 years old.

- Rotavirus seems to be more prevalent in older, unvaccinated children, as a result of pervasive vaccination programs. In low-income nations where rotavirus vaccines are uncommon, the incidence of rotavirus infections appears stable. In these regions, malnutrition tends to exacerbate the severity of disease.

Structure of Rotavirus

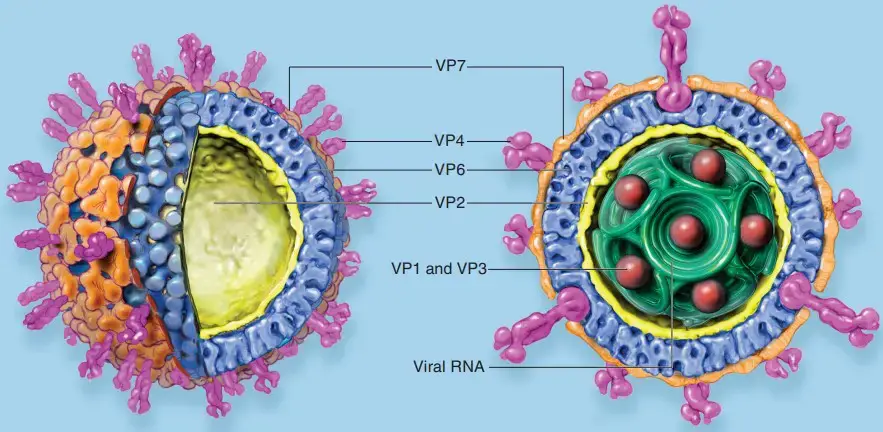

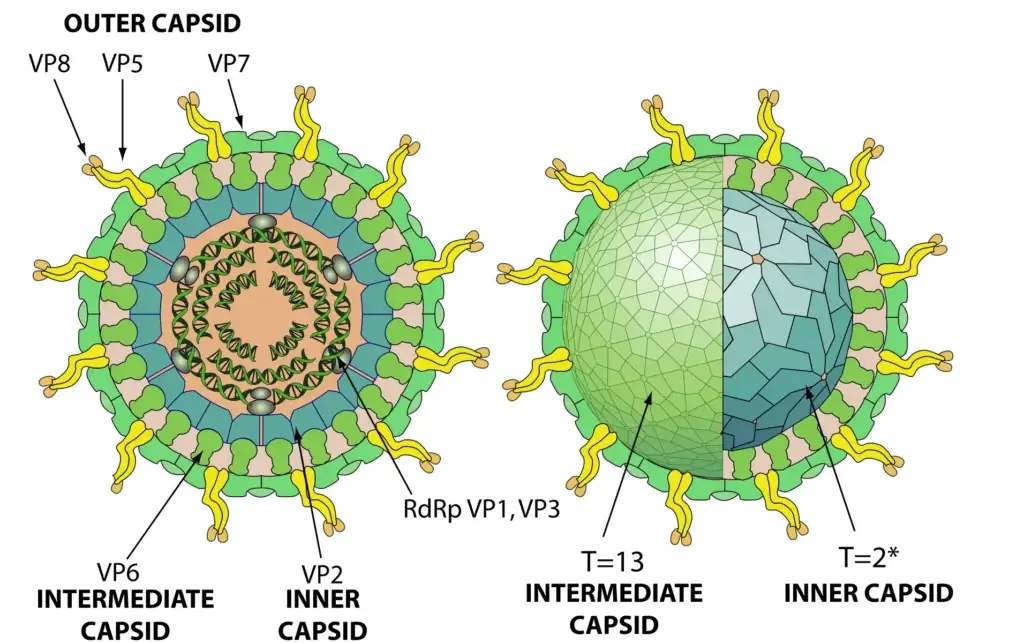

- Rotaviruses were given their name because, under classical electron microscopy, they appear as 70 nanometer particles shaped like wheels (rota).

- Cryoelectron microscopy (a technique that allows visualization of the viral spikes) reveals that the diameter of the virus is 100 nm. Using this method, the virus particle has been shown to be formed by three concentric layers of proteins: the core comprises viral structural protein 2 (VP2), the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (VP1), guanyl tranferase (VP3), and the viral genome, the intermediate layer is formed by structural protein VP6, the most abundant and most antigenic viral protein, and the external layer comprises 780 copies of glycoprotein VP7 and 60 viral spikes formed by VP4.

- There are three kinds of pores on the surface of the virion that penetrate the interior of the capsid. These channels appear to play an essential role in viral replication, allowing the exchange of compounds in aqueous solution with the interior of the capsid and the export of RNA transcripts in their infancy.

- Multiple RV structural proteins and nonstructural proteins (NSPs) have been crystallized, allowing detailed molecular investigations of viral physiology to commence. Using this technique, it was determined that viral spikes are composed of VP4 trimers, the structure of which rearranges upon trypsin cleavage (a process that enhances viral infection) and likely again upon entrance into the cell.

- These modifications resemble conformational transitions of enveloped virus membrane fusion proteins. The crystal structure of the viral hemaglutinin VP8, which contains several virus-neutralizing epitopes (VP4 is cleaved by trypsin into VP8 and VP5), has also been determined.

Genome of Rotavirus

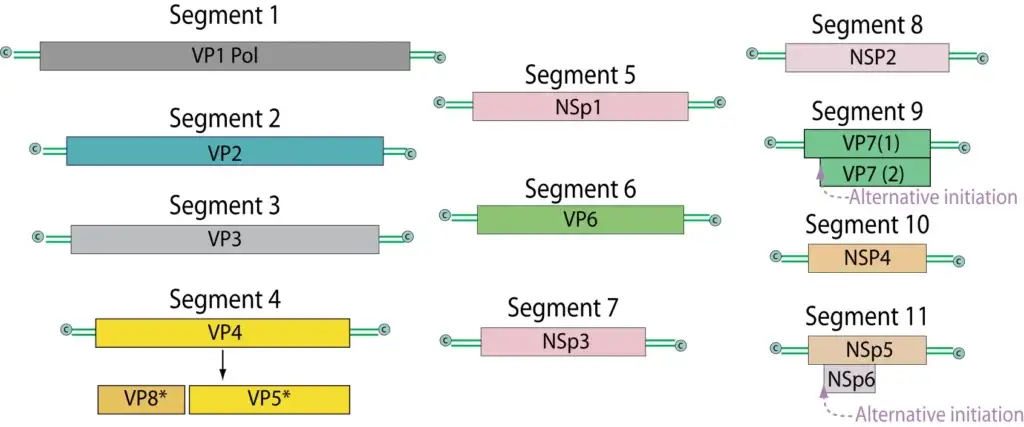

- There are 11 strands of double-stranded RNA in the RNA genome, and together they code for 12 different proteins.

- Six structural proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3, VP4, and VP6) are encoded by different RNA segments.

- Neutralizing epitopes are found on the outer capsid proteins VP4 and VP7, with VP7 glycoprotein being the most abundant antigen.

- Minor core proteins consist of VP1 (viral polymerase), VP2 (primary scaffolding protein), VP3 (capping enzyme), VP6 (most abundant rotavirus protein) (interacts with VP2 and outer capsid proteins VP7 and VP4), and VP7 (core protein) and VP4 (outer capsid proteins).

- There are a total of six nonstructural proteins encoded by the viral genome: NSP1, NSP2, NSP3, NSP4, NSP5, and NSP6.

- There is a 5′-methylated cap structure on the viral mRNAs, but no polyA tail.

- Instead, all 11 of the rotavirus genes share a 3′-terminal consensus sequence (UGACC).

linear segmented dsRNA genome. Includes 11 segments that code for 12 proteins. (SiRV-A/SA11) Segment sizes range from 667 to 3,302nt. Total genome size is 18,550 base pairs (SiRV-A/SA11). The viral mRNAs have 5′-methylated cap structures, but no polyA tail. Instead, rotavirus mRNAs have a consensus sequence (UGACC) at their 3′ end that is shared by all 11 viral genes. Co-infection of cells with distinct rotavirus strains belonging to the same serogroup A, B, or C results in genetic reassortment (mixing of genome segments).

Replication of Rotavirus

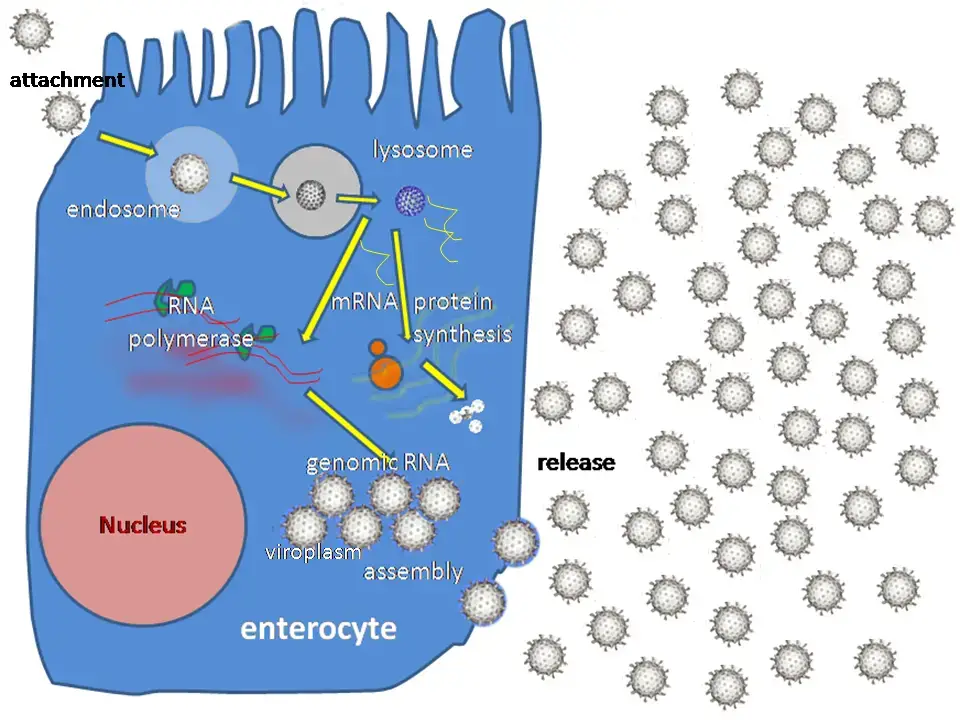

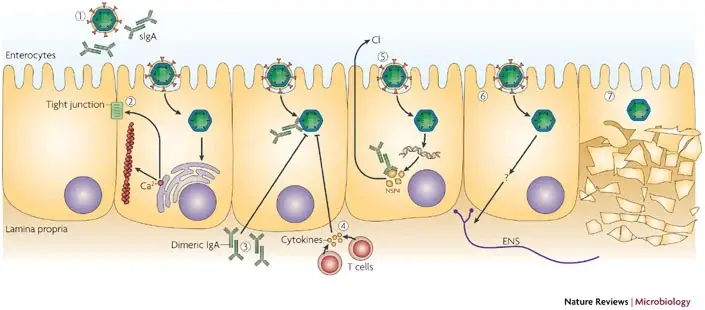

The Replication stages are in above image:

- Attachment of the virus to the host cells, which is mediated by the proteins VP4 and VP7

- Penetration of the cell by the virus and uncoating of the viral capsid are mediated by VP1, VP3, and VP2 in addition to Plus strand ssRNA (mRNA) synthesis.

- Formation of viroplasm, packaging of viral RNA, synthesis of minus strand RNA, and formation of double-layered virus particles.

- The maturation and release of virus progeny particles.

- Attachment of the viral VP4 protein to host receptors mediates the entry of the virus into the host cell via clathrin.

- In endolysosomes, particles become partially uncoated (VP4-VP7 outer layer loss) and enter the cytoplasm via permeabilization of the endosomal membrane of the host.

- Early transcription of the dsRNA genome by viral polymerase occurs within these double-layered particles (DLPs), preventing dsRNA exposure to the cytoplasm. The (+)RNAs are expelled into the cytoplasm and serve as a template for the synthesis of viral proteins.

- In cytoplasmic virus factories (also known as viroplasms), progeny nuclei with replicase activity are generated. This necessitates the synthesis of complementary (-)RNA as well as the initiation of viral morphogenesis.

- These progeny centers exhibit delayed transcription.

- These cores are coated with VP6 at the periphery of virus factories, forming immature DLPs that bud across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, acquiring a transient lipid membrane that is modified with the ER resident viral glycoproteins NSP4 and VP7; these enveloped particles also contain VP4. As the particles progress towards the interior of the ER cisternae, the transient lipid membrane and the nonstructural protein NSP4 are lost, while the virus surface proteins VP4 and VP7 rearrange to form the outermost viral protein layer, resulting in the formation of mature infectious triple-layered particles.

- Presumably, mature virions are released following cell death and the concomitant breakdown of the plasma membrane of the host.

Pathogenesis of Rotavirus

- Rotavirus is a highly contagious virus that infects cells in the villi of the small intestine. Once inside the cells, the virus multiplies in the cytoplasm of enterocytes and damages their transport mechanisms, which prevent the absorption of water, leading to a net secretion of water and loss of ions that result in watery diarrhea.

- The NSP4 protein of rotavirus acts in a toxin-like manner and promotes calcium ion influx into enterocytes, which causes the release of neuronal activators and an alteration in water absorption, contributing to the development of diarrhea. Additionally, rotavirus infection may impair sodium and glucose absorption as damaged cells on villi are replaced by non-absorbing immature crypt cells.

- Furthermore, the damaged cells can slough into the lumen of the intestine and release large quantities of viruses, which appear in the stool. Viral excretion usually lasts from 2 to 12 days in otherwise healthy patients, but it can be prolonged in those with poor nutrition and immunocompromised patients.

- The loss of fluids and electrolytes can lead to severe dehydration and even death if therapy does not include electrolyte replacement. Immunity to infection requires the presence of antibodies, primarily immunoglobulin A (IgA), in the lumen of the gut. Antibodies to the VP7 and VP4 can neutralize the virus and provide immunity to future infections.

Transmission of Rotavirus

- Rotaviruses are transmitted through the fecal-oral route, through contact with contaminated hands, surfaces, and objects[66], and potentially through the respiratory route.

- Diarrhea caused by a virus is very contagious. Les feces of an infected individual can contain more than 10 trillion infectious particles per gram; less than 100 of these are required to transmit infection to another individual.

- Rotaviruses are stable in the environment and have been detected at up to 1–5 infectious particles per US gallon in estuary samples. The pathogens have a 9 to 19 day lifespan.

- As the incidence of rotavirus infection is similar in countries with high and low health standards, it appears that sanitary measures adequate for eradicating bacteria and parasites are ineffective in controlling rotavirus.

Clinical manifestations of Rotavirus

- Rotaviral enteritis is characterized by nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhea, and low-grade fever. Once a child is infected with the virus, there is a two-day incubation period before the onset of symptoms.

- The duration of the disease is acute. Typically, symptoms begin with vomiting, followed by four to eight days of diarrhea.

- Dehydration is more prevalent in rotavirus infections than in those caused by most bacterial pathogens and is the leading cause of mortality associated with rotavirus infections.

- Rotavirus infections can occur throughout life; however, subsequent infections are typically mild or asymptomatic because the immune system provides some protection.

- Consequently, the prevalence of symptomatic infections is greatest in children younger than two years of age and decreases with age up to 45.

- Children aged six months to two years, the elderly, and those with immunodeficiency typically experience the most severe symptoms.

- Due to childhood-acquired immunity, the majority of adults are not susceptible to rotavirus; gastroenteritis in adults is typically caused by something other than rotavirus, but asymptomatic infections in adults may maintain the transmission of the infection in the community. There is some evidence that blood group can influence the susceptibility to rotavirus infection.

Diagnosis of Rotavirus

- There are several laboratory methods available to diagnose rotavirus infection. The most common method is the detection of the virus in stool samples using enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) or rapid antigen detection tests (RADTs).

- EIAs detect viral antigens in stool specimens and are sensitive, specific, and relatively easy to perform. RADTs are similar to EIAs but can provide results within 15-30 minutes, making them useful in clinical settings.

- Another method to diagnose rotavirus infection is electron microscopy, which can visualize viral particles in stool specimens. However, this method is less sensitive than EIAs or RADTs.

- Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is a more sensitive and specific method for detecting rotavirus RNA in stool specimens. This method can also distinguish between different strains of rotavirus.

- In some cases, viral culture can be used to isolate rotavirus from stool specimens. However, this method is time-consuming and requires specialized laboratory facilities.

Treatment of Rotavirus

- The treatment of rotavirus infection primarily involves supportive care to manage dehydration and electrolyte imbalances caused by diarrhea and vomiting.

- Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is the cornerstone of treatment for rotavirus infection. ORT involves the administration of a solution containing water, salts, and sugars to replace fluids and electrolytes lost due to diarrhea and vomiting. Commercially available oral rehydration solutions (ORS) are widely available and are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the treatment of dehydration caused by rotavirus infection.

- In severe cases of dehydration, intravenous fluids may be necessary to replenish fluids and electrolytes. Antiemetic and antidiarrheal medications are generally not recommended as they can prolong the duration of infection and increase the risk of complications.

- There are currently no specific antiviral drugs approved for the treatment of rotavirus infection. However, research is ongoing to develop effective antiviral therapies.

- Prevention of rotavirus infection through vaccination is the most effective strategy for reducing the burden of disease. Two oral rotavirus vaccines are currently available and recommended for routine immunization in many countries. These vaccines have been shown to be highly effective in preventing severe rotavirus disease and reducing hospitalizations and deaths due to rotavirus infection.

Prevention and control of Rotavirus

Prevention and control of rotavirus infection involve several measures including:

- Vaccination: Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent rotavirus infection. Two safe and effective oral vaccines are available and recommended for routine immunization in many countries. These vaccines are highly effective in preventing severe rotavirus disease and reducing hospitalizations and deaths due to rotavirus infection.

- Hand hygiene: Rotavirus is primarily spread through fecal-oral transmission. Practicing good hand hygiene, such as washing hands with soap and water after using the toilet or changing diapers, can help prevent the spread of infection.

- Environmental sanitation: Proper sanitation and hygiene can help prevent the spread of rotavirus infection. This includes keeping surfaces clean and disinfected, particularly those that come into contact with fecal matter.

- Exclusive breastfeeding: Breastfeeding provides infants with protective factors against rotavirus infection and other illnesses. Infants who are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life are less likely to develop severe rotavirus disease.

- Isolation and treatment of cases: Infected individuals should be isolated to prevent the spread of infection. Treatment should focus on supportive care, including oral rehydration therapy to manage dehydration and electrolyte imbalances caused by diarrhea and vomiting.

- Health education: Health education campaigns can raise awareness about the risks and consequences of rotavirus infection, and promote practices that can help prevent its spread.

FAQ

What is rotavirus?

Rotavirus is a virus that causes gastroenteritis, which is inflammation of the stomach and intestines. It is one of the most common causes of severe diarrhea in infants and young children.

How is rotavirus spread?

Rotavirus is primarily spread through the fecal-oral route, which means that it is passed from person to person through contaminated food or water, or by touching surfaces that are contaminated with the virus and then putting your hands in your mouth.

What are the symptoms of rotavirus infection?

The symptoms of rotavirus infection include vomiting, watery diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain. In severe cases, dehydration can occur, which can be life-threatening, especially in young children and infants.

How long does it take for rotavirus symptoms to appear?

The incubation period for rotavirus is approximately 1-3 days. Symptoms usually appear within this time frame.

How is rotavirus diagnosed?

Rotavirus can be diagnosed through laboratory tests that detect the presence of the virus in stool samples. These tests are usually performed in a medical laboratory.

Is there a vaccine for rotavirus?

Yes, there are two oral vaccines available to prevent rotavirus infection. These vaccines are recommended for routine immunization of infants in many countries.

How is rotavirus treated?

There is no specific treatment for rotavirus infection. The focus of treatment is on managing symptoms and preventing dehydration. Oral rehydration therapy is often recommended to replace fluids lost through diarrhea and vomiting.

How long does rotavirus last?

The duration of rotavirus infection can vary, but it typically lasts for 3-7 days. In some cases, symptoms may last longer.

How can rotavirus be prevented?

Rotavirus can be prevented through good hand hygiene, proper sanitation and hygiene practices, and vaccination. Breastfeeding may also provide some protection against rotavirus infection.

Is rotavirus a serious illness?

Rotavirus can be a serious illness, particularly in young children and infants. In some cases, it can lead to severe dehydration, which can be life-threatening. However, most people recover from rotavirus infection without complications.

good information about rotaviurs