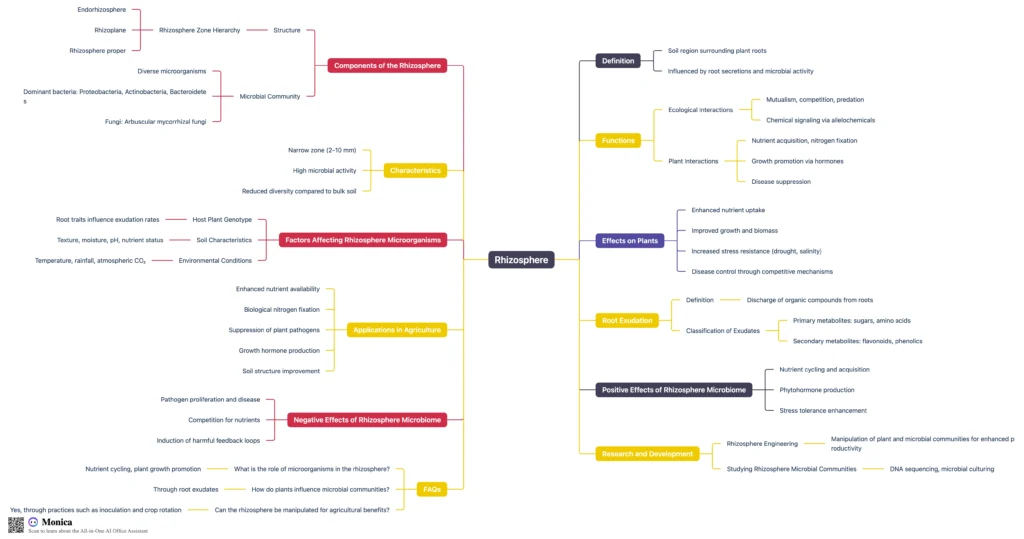

What is Rhizosphere?

The rhizosphere is the small area of soil around plant roots that is directly affected by root secretions and the microbes that live there.

Usually goes about one millimeter from the root surface and includes soil that sticks to the roots and can be easily shook off.

Root exudates and rhizodeposition: Roots emit sugars, organic acids, amino acids, mucilage, and proteins that feed soil microbes and change the pH and chemistry of the soil.

This is where bacteria, fungus, archaea, protozoa, nematodes, and viruses live. They are frequently very common but not as diverse as bulk soil. These microbes help plants develop, cycle nutrients, and fight off diseases.

Ecological interactions include mutualism (such nitrogen-fixing rhizobia and mycorrhizal fungus), competition, predation, and even allelopathy, which is when toxins stop surrounding plants or bacteria from growing.

Origin in history: German scientist Lorenz Hiltner came up with the name in 1904 to describe the root-soil interface that chemicals from roots control.

This biogeochemical zone is very active and important for taking in nutrients, cycling carbon, storing carbon in the soil, and keeping plants healthy. It is important for agriculture and ecosystem function around the world.

Definition of Rhizosphere

The rhizosphere is the narrow layer of soil immediately surrounding plant roots. It is directly influenced by root secretions and exudates, which enrich the area with nutrients. This zone hosts a dense and diverse community of microorganisms that support plant growth and nutrient cycling

What is Rhizosphere effect?

- The rhizosphere effect is the sum of the biological, chemical, and physical changes that happen in the soil surrounding plant roots when root exudates and rhizodeposition happen. These changes impact the properties of the soil and microbes.

- Root secretions make microorganisms (bacteria, fungus, actinomycetes, and protozoa) grow faster, which can raise the amount of microbes in the soil by 5 to 20 times or even 100 times. This is evaluated by the R/S ratio (rhizosphere/bulk).

- Exudates change the soil’s chemistry and pH, dissolve nutrients, break down organic matter, and release new compounds through microbial decomposition.

- Polysaccharides and mucilage from roots and microorganisms stick to soil particles, making them stick together better and giving the soil better structure and resistance to erosion.

- Microbial community structuring—plants bring in certain microorganisms (such PGPR, rhizobia, and mycorrhizae) that change the community structure from that of bulk soil. This is done by selective filters based on exudate composition and root characteristics.

- Better nutrient transformation, breaking down organic matter, carbon cycling (including the rhizosphere priming effect), disease control, and growth stimulation through interactions between roots and microbes.

- Gradient gradient nature, the effect intensity is weaker as you get away from the root surface. The biological and chemical effects get weaker as you move from the rhizoplane to the bulk soil.

Definition of Rhizosphere effect

The rhizosphere effect is the marked increase in microbial activity and chemical changes in the narrow soil zone surrounding plant roots. It is driven by root exudates that provide energy and nutrients, stimulating a diverse community of soil microorganisms. This enhanced microbial activity improves nutrient cycling, promotes plant growth, and aids in suppressing soilborne diseases. The phenomenon highlights the dynamic and beneficial interactions between plant roots and their associated soil microbes.

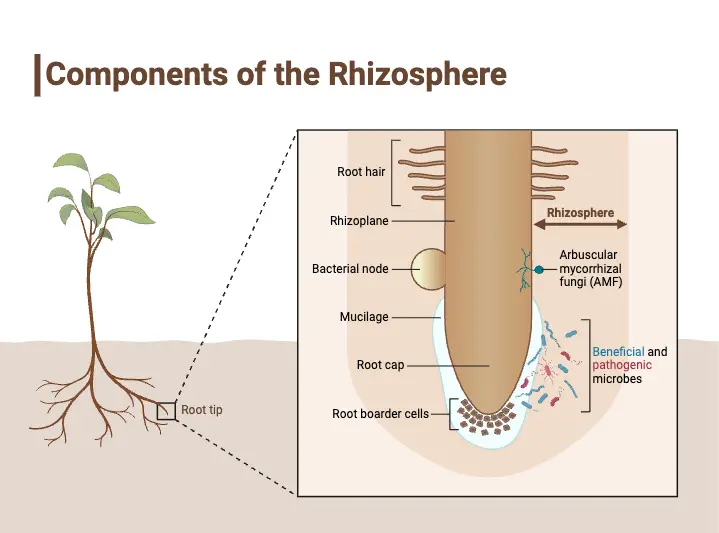

Structure of Rhizosphere

- Rhizosphere zone hierarchy

- it includes the endorhizosphere – the inner cortex and endodermis regions where microbes occupy apoplastic spaces

- then the rhizoplane – the root epidermis plus tightly adhered mucilage and soil particles at root surface .

- beyond that the rhizosphere proper – narrow region of soil influenced by root exudates and microbial activity

- Mucigel / root mucilage

- it forms slimy hydrated polysaccharide layer from root cap cells, lubricates root tip, protects and creates diffusion bridge, retains microbes

- Root hairs

- lateral outgrowths of epidermal cells increasing surface area, aiding water/mineral uptake, microbial interface and exudation.

- Root exudates (rhizodeposits)

- sugars, organic acids, amino acids, phenolics − secreted actively or passively into soil, altering chemistry, recruiting microbes, nutrient cycling.

- Soil matrix components

- includes soil particles, organic matter, water films, microbial biofilms adhering across rhizoplane and rhizosphere proper.

- Microbial community structure

- rhizosphere recruits subset of bulk soil microbiome, lower alpha‑diversity, enriched in copiotrophic bacteria (Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria).

- fungi such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Trichoderma spp. often key functional members interacting with plant roots.

- Network architecture & stability

- microbial co‑occurrence networks in rhizosphere show fewer edges, more modules, less stability than bulk soil networks.

- Ecological interactions within rhizosphere

- includes mutualism (e.g. rhizobia‑legume nodulating bacteria), competition and predation (nematodes, protists), chemical communication via allelochemicals and signalling compounds.

Characteristics of Rhizosphere

- Rhizosphere narrow zone – it’s the soil immediately surrounding roots, typically 2–10 mm wide, directly influenced by root secretions, mucilage and sloughed cells.

- High microbial activity – it shows intense biological processes, carbon and nitrogen cycling driven by enriched microbial communities fueled by root exudates.

- Reduced microbial diversity – compared to bulk soil, diversity is often lower, with dominance of copiotrophic bacteria (Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes etc.) selected from bulk assemblage

- Distinct community structure – rhizosphere microbiome differs taxonomically and functionally from both bulk soil and root endophytes, reflecting plant‑driven selection.

- Chemical modifications – root exudates alter soil pH, nutrient availability, metal chelation and drive allelopathy or signalling, influencing surrounding plants and microbes.

- Physical changes

- it creates soil particle aggregation via mucilage and exopolysaccharides improving soil structure, water retention and reducing erosion.

- a gelatinous mucilage layer adheres to root surface retaining moisture and microbes, facilitating diffusion bridges

- Ecological interactions

- mutualism with nitrogen‑fixing bacteria (rhizobia) and mycorrhizal fungi providing nutrients in exchange for carbon

- competition and predation from nematodes, protists and antagonistic microbes shaping community composition

- Chemical signalling network – complex inter‑kingdom communication mediated by exudates, allelochemicals, quorum sensing molecules leading to regulatory shifts in gene expression among microbes and plants.

- Functional enrichment

- elevated abundance of genes for carbon and nitrogen transformation, phosphate solubilization bacteria active in nutrient mobilization.

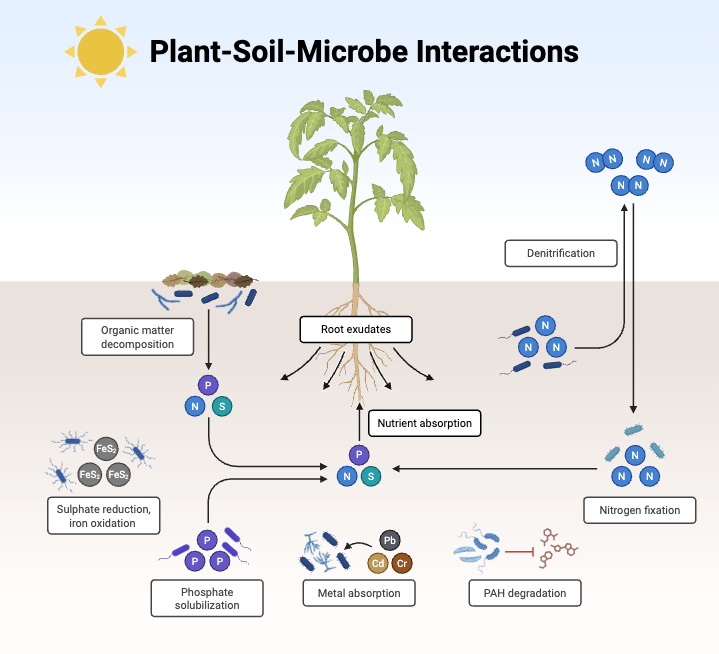

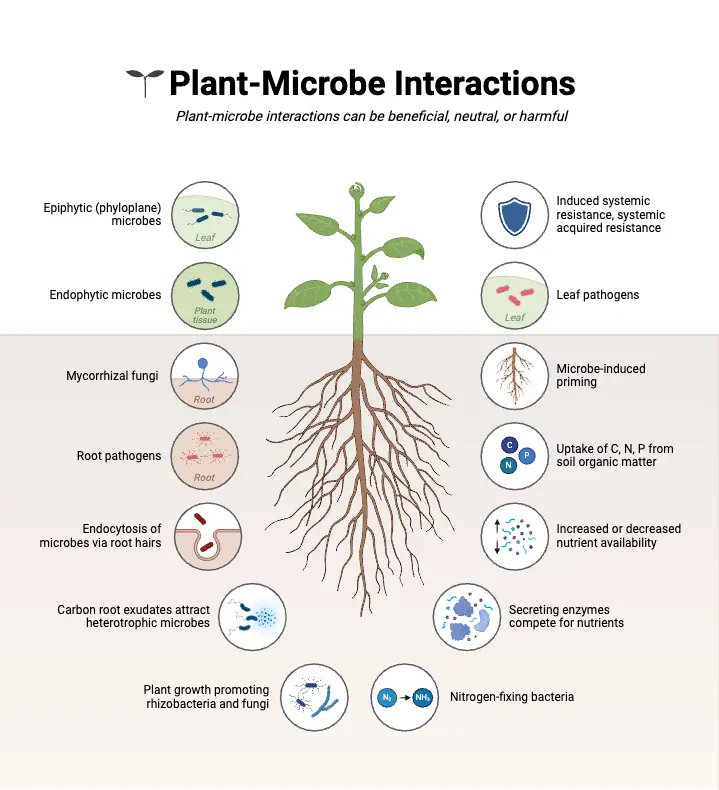

Effects of rhizosphere microbial populations on Plants

- Nutrient acquisition – rhizosphere microbes, especially mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate solubilizing bacteria, enhance plants nutrient uptake by converting insoluble minerals, like phosphates, into plant‑accessible forms, making nutrients easier to absorb.

- Nitrogen fixation – symbiotic rhizobia bacteria fix atmospheric nitrogen inside legume root nodules, converting it into ammonia, thus providing plants with essential nitrogenous compounds for growth, this improves overall plant vigor and biomass.

- Growth promotion – rhizobacteria (PGPRs) produce growth hormones, such as auxins, cytokinins, and gibberellins, which stimulate root development and enhance overall plant growth, ultimately improving plant productivity.

- Disease suppression – beneficial microbes in the rhizosphere outcompete pathogens by producing antimicrobial compounds like antibiotics, siderophores, and volatile organic compounds, thus reducing diseases and protecting plants.

- Stress resistance – rhizosphere microbial populations help plants cope with environmental stresses, like drought or salinity, by enhancing stress tolerance mechanisms through modulation of plant hormone signaling pathways, like ethylene or abscisic acid production.

- Allelopathic effects – microbial populations influence allelochemical availability by metabolizing root exudates, altering plant-plant interactions in the rhizosphere, and this can indirectly impact competition and plant growth.

- Root system architecture modification – certain rhizosphere bacteria stimulate increased root hair formation and branching, improving soil exploration and nutrient capture efficiency, resulting in healthier plants with better soil anchoring.

- Enhanced soil structure – rhizosphere microbes release polysaccharides, contributing to improved soil aggregation and water holding capacity, creating favorable conditions around the plant roots, which further supports plant health.

- Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) – beneficial rhizosphere microbes trigger systemic resistance in plants against pathogens, priming plant immune responses through signaling pathways involving jasmonic acid and salicylic acid.

- Influence on flowering and yield – microbial interactions in the rhizosphere can also influence flowering time and reproductive development, leading to enhanced crop yield or quality, often due to microbial modulation of hormone production or nutrient availability.

Microorganisms found in Rhizosphere (The Rhizosphere Microbiome)

- Bacteria

- Proteobacteria – dominant in rhizosphere, includes genera like Rhizobium, Pseudomonas, Azospirillum, Acidibacter, and Nitrosospira

- Actinobacteria – includes Streptomyces rhizosphaericola, Gaiella, Blastococcus, Nocardioides, and Conexibacter

- Bacteroidetes – includes Pedobacter, Flavobacterium, Chitinophaga, and Chryseobacterium

- Firmicutes – includes Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Bacillus subtilis

- Acidobacteria – includes Acidobacterium capsulatum, involved in nutrient cycling and plant growth promotion

- Cyanobacteria – includes Nostoc, Anabaena, and Calothrix, which fix nitrogen and colonize roots

- Fungi

- Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) – form symbiotic relationships with plants, enhancing nutrient uptake

- Penicillium radicum – isolated from wheat rhizosphere, promotes plant growth by solubilizing inorganic phosphates

- Trichoderma harzianum – endophytic fungus with antimicrobial activity against plant pathogens

- Archaea

- Methanogens, Ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA), and Nitrate-reducing archaea are present in the rhizosphere, contributing to nitrogen cycling and methane oxidation

- Eukaryotes

- Nematodes – influence plant health through interactions with roots

- Protozoa – affect microbial community dynamics and nutrient cycling

- Oomycetes – include plant pathogens like Pythium and Phytophthora

- Algae – contribute to nutrient cycling and may form symbiotic relationships with plants

- Arthropods – influence plant health and microbial community structure

- Viruses

- Viruses infecting bacteria (bacteriophages) and fungi are present, influencing microbial populations and plant health

Factors Affecting Rhizosphere Microorganisms

- Host plant genotype and root traits - plant genetic makeup and root morphology determine exudation rates, root tissue properties (e.g. RTD, branching), and select distinctive microbial taxa from bulk soil to establish functional microbiome assembly

- Root exudation composition and amount — amounts of released sugars, amino acids, organic acids and secondary metabolites are species-, stage-, nutrient status-, and herbivore-sensitive and they govern microbial recruitment, competition and activity

- Soil physicochemical characteristics - soil type, texture, SOC, N, P, moisture content, pH, aeration and organic additions (humic substances) significantly determine microbial biomass, diversity and community structure

- Environmental abiotic parameters — the temperature, rain/drought patterns, atmospheric CO₂ and climatic parameters shape microbial respiration, growing and dormant phases, and hence alter community dynamics within the rhizosphere

- Bulk soil microbial richness and reservoir — microbial taxonomic units present in bulk soil act as source pool; rhizosphere selects subset that prefers copiotrophic fast‑growing taxonomic units with numerous rRNA operons

- Top-down control — predation by nematodes, protists, bacteriophages, occurrence of pathogens, mycorrhizae, and oomycetes shape community assembly and suppressive ability

- Plant health and pathogen status — Infection triggers shifts in microbial composition in favor of pathogen-suppressive taxa or dysbiosis; domestication history also impacts assembly of the microbiome

- Agronomic management and anthropogenic impacts — tilling, fertilization (especially nitrogen), pesticides, crop rotation and organic amendments alter microbial diversity, richness and functional potential

- Microbial growth traits - bacteria with high predicted growth rate potential are consistently enriched and dominate rhizosphere communities over slower‑growing counterparts

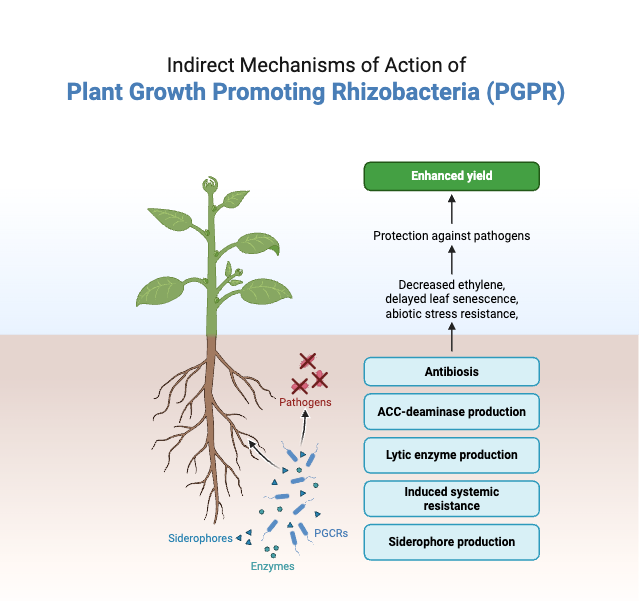

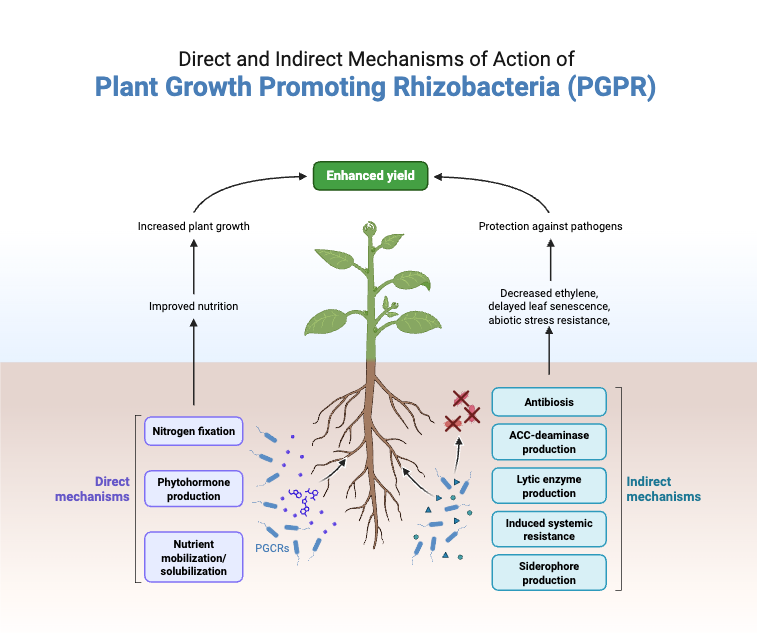

What is Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR)?

- Definition – PGPR are bacteria that colonize the rhizosphere, the soil region near plant roots, and improve plant growth and health by direct and indirect mechanisms

- Direct modes – they offer atmospheric nitrogen fixation, phosphorus and other microelements solubilization, secretion of siderophores to chelate iron, and phytohormone production such as auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins

- Indirect modes – they suppress phytopathogens through iron and nutrient competition, generate antibiotics or lytic enzymes, and create systemic plant resistance (ISR) to stimulate disease tolerance

- Abiotic-stress alleviation – PGPR assist in making crops tolerant to drought, salinity, heavy metal toxicity through shifting root architecture, enhancing water/nutrient assimilation, shifting metal availability, enhancing antioxidant metabolism

- Common genera – include Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Rhizobium, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Burkholderia, Acinetobacter, Flavobacterium, Mesorhizobium among others

- Role as biofertilisers / biocontrol agents – PGPR are used in seed coatings or soil amendments to reduce synthetic fertiliser use, promote sustainable crop yields and suppress soilborne pathogens

They are usually classified as endophytic (within plant tissues) or rhizospheric (outside colonisers), and few percentages of bacteria in the rhizosphere are PGPR but they contribute a significant share to soil fertility and plant productivity

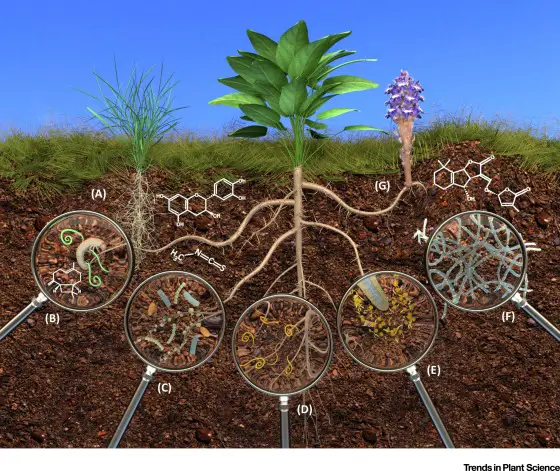

Types of Microbial Interactions found in the Rhizosphere

- Microbe‑to‑plant mutualism ‑ fungi such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic associations with plant roots, exchanging nutrients (C for P, N)

- Plant‑to‑microbe signaling ‑ root exudates (like strigolactones, Myc‑factors, flavonoids) recruit specific microbial taxa to colonize.

- Microbe‑to‑microbe competition ‑ microbes compete for space, nutrients; PGPR exclude pathogens via siderophores or niche occupation.

- antifungal antibiosis (secondary metabolites, enzymes).

- Antagonism and biocontrol ‑ hyperparasitism where one microbe parasitizes another (e.g. mycoparasitic fungi attacking pathogenic fungi), or induction of host plant resistance

- Hyperparasitism / mycoparasitism ‑ fungi or bacteria parasitize other fungi; can be biotrophic or necrotrophic, killing or coexisting.

- Predation / protist‑microbe interactions ‑ protists feed on bacteria, triggering bacterial toxin production or biocontrol gene expression

- Biofilm formation ‑ microbial biofilms (e.g. Bacillus, Pseudomonas on roots) aid in colonization, induce systemic resistance in plants.

- Quorum‑sensing and inter‑kingdom signaling ‑ microbes use chemical signals (volatiles, peptides) to coordinate behaviour, some affect fungi, insects and plants.

- Commensalism ‑ some microbes benefit from root exudates without harming or benefitting the plant, simply coexisting in rhizosphere chemistry.

- Neutral or context‑dependent associations ‑ interactions vary along mutualism‑parasitism continuum depending on environment and host physiology

What is Root Exudation?

- Root exudation refers to the discharge of organic molecules from living plant roots into the adjacent soil, hence creating a nutrient-rich rhizosphere environment.

- Exuded compounds encompass low-molecular-weight metabolites (sugars, amino acids, organic acids), secondary metabolites (phenolics, flavonoids, auxins), mucilage, and border-cell lysates.

- Mechanisms involve a combination of passive diffusion, particularly at the root apex, and active secretion through efflux carriers. Passive processes are driven by concentration gradients, however plants can regulate these mechanisms through transporter expression and source/sink dynamics.

- Exudation is localized at the root apex due to the absence of cellular structure. Casparian strip

- Functions – provide carbon for rhizosphere microorganisms, influences soil microbial community structure, communicates with symbionts (e.g., mycorrhizae, rhizobia), and facilitates the mobilization of nutrients such as phosphorus, iron, and nitrogen.

- Ecological function – facilitates nutrient cycling, stimulates rhizosphere priming, creates microbial activity hotspots, and affects root architecture through the detection of exudate concentration gradients.

- Adaptive regulation – plants modulate exudation rates in response to nutrient availability or environmental stimuli by altering phloem loading/unloading and efflux transporter activity.

Classification of Root Exudates

Root exudates are classified generally into primary and secondary metabolites based on chemical nature and function, and also by how they are released: diffusates, secretions, excretions, with diffusive, active and borderline mechanisms

- Primary metabolites ‑ include sugars (glucose, fructose, sucrose), amino‑acids (lysine, tryptophan, threonine), organic‑acids (malic, acetic, oxalic), often passively loss at root apex, serve as nutrients for microbes

- Secondary metabolites ‑ flavonoids, phenolic compounds, volatiles, allelochemicals; these act as signals, antimicrobials, microbial attractants or deterrents

- Sugar alcohols & lipids ‑ included among secondary but sometimes treated separately; act in chemotaxis, signaling, microbial recruitment

- Exopolysaccharides/mucilage ‑ polysaccharide‑rich gelatinous secretions from root cap cells or border cell lysates; form physical matrix, retain water, structure soil and microbes around root.

Classification by molecular weight ‑ low molecular weight (LMW) compounds like sugars, amino‑acids, organic‑acids; high molecular weight polymers such as mucilage and exopolysaccharides.

Functions of Root Exudates

- Nutrient supply and microbial fuel ‑ root exudates provide labile carbon sources (sugars, amino‑acids, organic acids, vitamins, enzymes) fueling microbial respiration and cycling of nutrients in the rhizosphere, up to 20–40 % of plant‑fixed carbon is released as exudates

- Microbial recruitment and signalling ‑ exudates act as chemoattractants and molecular signals recruiting beneficial microbes (PGPR, rhizobia, mycorrhizal fungi) shaping rhizobiome assembly and plant‑microbe mutualism

- Defense and suppression ‑ secondary metabolites in exudates (phenolics, flavonoids, phytoalexins) inhibit pathogens, disrupt quorum‑sensing, and prime plant immunity and disease suppressive soil formation

- Micro‑environment modification ‑ mucilage (exopolysaccharides) alters rhizosphere hydrophobicity, retains water, lubricates root movement, stabilizes soil structure, and creates favourable conditions for symbionts

- Resource mobilization ‑ organic acids and phytosiderophores chelate micronutrients (Fe, Mn, Zn), improving nutrient solubility and uptake under deficiency conditions

- Microbial community shaping ‑ exudate compounds influence microbial diversity and functional traits, promoting beneficial species while suppressing harmful ones, affecting carbon metabolism and community structure.

- Stress adaptation signalling ‑ under abiotic or biotic stress (drought, nutrient deficiency, disease), plants alter exudate profiles (e.g. ABA, proline, malate, flavonoids) to attract stress‑mitigating microbes

Factors Affecting Root Exudation

- Plant species and genotype ‑ species and cultivar differences strongly influence both quantity and spectrum of exuded metabolites due to genetic control of transporter expression and metabolic pathways.

- Plant developmental stage and root architecture ‑ younger roots, root tips exude more compounds passively; root branching, density, age affect exudation profile and diffusion zones .

- Soil nutrient status ‑ nutrient deficiencies (eg low phosphorus, iron, nitrogen) trigger enhanced exudation of organic acids, coumarins, phenolics to mobilize nutrients or attract symbionts.

- Soil moisture and water stress ‑ drought or excess water alter exudation rates; under water deficit plants upregulate mucilage, organic acids and other osmotic compounds

- Soil pH, texture and composition ‑ pH changes shift solubility and microbial response; soil type and matrix influence diffusion and retention of exudates thereby modifying plant exudation patterns

- Temperature and light intensity ‑ higher irradiance and warmth increase photosynthesis and carbon allocation to roots, elevating exudation flux; low light reduces root C supply and exudate release

- Biotic interactions (microbes, pathogens, herbivores, neighbours) ‑ microbial colonization, beneficial or pathogenic, and herbivory induce altered exudate profiles acting as signals or defense; neighbouring plants influence kin‑recognition responses

- Abiotic stresses (salinity, heat, heavy metals) ‑ these stresses modify root exudate quality and quantity, triggering secretion of osmoprotectants, antioxidants, chelators to mitigate stress effects.

- Plant source‑sink dynamics and transporter regulation ‑ carbon allocation from shoots to roots and expression of efflux transporter proteins (eg SWEET, GDU, CAT) calibrate diffusion and active release of primary metabolites

Positive effects of rhizosphere microbiome

- Nutrient acquisition and solubilization ‑ microbes in rhizosphere fix nitrogen (e.g. rhizobia), solubilize phosphorus via organic acids and phosphatases, chelate iron through siderophores, improving plant nutrient uptake and growth efficiency.

- Phytohormone production and growth regulators ‑ PGPR produce auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins and interfere with ethylene metabolism, stimulating root growth, branching and plant vigor.

- Disease suppression and biocontrol ‑ beneficial microbes inhibit pathogens via antibiosis, competition, and induction of systemic resistance (ISR), leading to disease‑suppressive soils and reduced chemical pesticide reliance.

- Stress tolerance enhancement ‑ microbial associations (mycorrhizae, PGPR) help plants counter abiotic stresses like drought, salinity, heavy metal toxicity and nutrient deficit by improving water uptake, chelation and stress signalling

- Microbial community shaping and legacy effects ‑ plants select and enrich beneficial taxa via exudates, leading to stable rhizosphere communities that predict higher crop productivity especially under crop rotation or domestication regimes

- Soil structure improvement and carbon sequestration ‑ mycorrhizal hyphae and secreted glomalin enhance soil aggregation and organic carbon storage, improving soil stability and fertility

- Priming of soil nutrient cycles ‑ microbial activity stimulated by rhizosphere carbon inputs accelerates decomposition and nutrient mineralization in hotspots, enhancing N and P availability (rhizosphere priming)

- Biofilm formation and immune priming ‑ root‑colonizing bacteria like Pseudomonas, Bacillus form biofilms on roots, triggering induced systemic resistance by activating plant defence genes and strengthening cell walls

Negative Effects of rhizosphere microbiome

- Pathogen proliferation and disease ‑ presence of soil‑borne pathogens like pathogenic fungi, oomycetes, bacteria, nematodes in rhizosphere can infect roots causing wilts, root rots, galls (e.g. Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Ralstonia, Pectobacterium) and reduce plant health and yield

- Deleterious rhizobacteria (DRB) ‑ certain bacterial genera (e.g. Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Flavobacterium, Arthrobacter) reduce seed germination, distort roots, cause lesions and yield reductions up to ~48 % in sugar beet

- Microbial competition for nutrients and niches ‑ non‑beneficial microbes compete with both plant roots and beneficial microbes for carbon and mineral nutrients, limiting growth or symbiotic associations

- Disruption of beneficial microbiome structures ‑ proliferation of pathogenic taxa can shift community structure, reducing microbial diversity and destabilizing beneficial plant-microbe interactions and disease suppressive capacity

- Rhizosphere dysbiosis and negative feedback loops ‑ repeated pathogen pressure or crop monoculture lead to dysbiotic rhizosphere, accumulation of harmful microbes and declining soil‑plant health over time

- Toxin or phyto‑toxin production ‑ some microbes or plant‑microbe feedbacks induce production of allelochemicals or toxins (eg benzoxazinoids) that suppress adjacent plant growth or alter root architecture negatively

- Opportunistic human pathogens in rhizosphere ‑ detection of bacteria like Salmonella, E. coli O157, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in root microbiome raises concern for human and livestock health from produce contamination.

- Induced susceptibility via microbial hijacking ‑ some fungi (eg mycorrhiza‑like) can manipulate host hormone signalling, occasionally hijacking plant pathways that may be pathogenic in certain contexts

Applications of Rhizosphere in Agriculture

- Enhanced nutrient uptake – rhizosphere microbes help dissolve phosphorus, zinc, iron etc., making them more bioavailable for root absorption

- mycorrhizal fungi extend root surface area

- PGPR solubilize insoluble minerals

- Biological nitrogen fixation – symbiotic bacteria like Rhizobium, Frankia fix atmospheric nitrogen into plant-usable ammonia

- essential in legumes, reduces need of synthetic N fertilizers

- Suppression of plant pathogens – rhizobacteria produce antibiotics, siderophores, lytic enzymes that inhibit harmful fungi and bacteria

- e.g., Pseudomonas spp. suppress Fusarium, Pythium pathogens

- Growth hormone production – many rhizobacteria produce auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins that stimulate root elongation, shoot growth

- this results in stronger, more productive plants

- Induced systemic resistance (ISR) – beneficial microbes trigger plant immune responses, making crops more resilient to diseases

- similar to plant vaccination effect

- Soil structure improvement – microbial polysaccharides, fungal hyphae stabilize soil aggregates and enhance water retention

- especially helpful in degraded, sandy, or compact soils

- Phytoremediation support – rhizosphere microbes detoxify heavy metals, degrade pesticides, and support plant-based cleanup in polluted soils

- Crop stress tolerance – microbes in rhizosphere help plants tolerate drought, salinity, and extreme pH by modulating stress hormones and osmolytes

- Weed suppression – certain root exudates attract microbes that release allelopathic compounds, which inhibit weed seed germination

- Biofertilizer and biopesticide development – isolates from rhizosphere are used in commercial agri-products to reduce chemical dependency

- e.g., Bacillus subtilis, Azospirillum, Trichoderma used in organic farming

- Yield improvement – all combined effects—nutrient mobilization, growth promotion, disease protection—translate into higher crop productivity

- Carbon sequestration – enhanced microbial activity in rhizosphere increases soil organic carbon content

- supports long-term soil health and climate resilience

- Precision agriculture integration – rhizosphere-based indicators (e.g., microbial diversity, enzyme activity) are used to monitor soil fertility zones for smart farming decisions

- Support intercropping & crop rotation – rhizosphere microbial dynamics influence compatibility of crop combinations

- helps design sustainable agro-ecosystems

Rhizosphere Mind Map/ Cheatsheet

FAQ

What is the rhizosphere?

The rhizosphere is the soil region surrounding the plant roots that is influenced by the plant’s root exudates and microbial activity.

What is the role of microorganisms in the rhizosphere?

Microorganisms in the rhizosphere play a crucial role in nutrient cycling, plant growth promotion, disease suppression, and overall soil health.

How do plants influence the rhizosphere microbial community?

Plants influence the rhizosphere microbial community through root exudation and by providing a source of carbon and other nutrients.

What is root exudate?

Root exudates are organic compounds secreted by plant roots into the surrounding soil that can influence the rhizosphere microbial community.

What is the difference between rhizosphere and bulk soil?

Rhizosphere is the soil region immediately surrounding the plant roots, while bulk soil refers to the soil farther away from the roots.

How do rhizosphere microorganisms promote plant growth?

Rhizosphere microorganisms can promote plant growth by fixing nitrogen, solubilizing nutrients, producing plant growth hormones, and suppressing plant pathogens.

What factors influence the rhizosphere microbial community?

Factors that influence the rhizosphere microbial community include plant species, soil type, nutrient availability, and environmental conditions.

Can the rhizosphere microbial community vary between different plant species?

Yes, the rhizosphere microbial community can vary between different plant species due to differences in root exudation and other factors.

How can we study the rhizosphere microbial community?

The rhizosphere microbial community can be studied using a variety of methods, including DNA sequencing, microbial culturing, and functional gene analysis.

Can we manipulate the rhizosphere microbial community to improve plant growth?

Yes, manipulating the rhizosphere microbial community through practices like crop rotation, cover cropping, and inoculation with beneficial microorganisms can improve plant growth and soil health.

What is the rhizosphere and why is it considered a “root galaxy”?

The rhizosphere is the narrow, dynamic zone of soil immediately surrounding plant roots. It’s often called the “root galaxy” because it’s a bustling, complex micro-ecosystem where intense chemical and biological interactions occur. This region, typically 2 to 10 mm thick, is directly influenced by substances released from plant roots, known as root exudates, as well as by the diverse community of microorganisms that thrive there. Compared to the “bulk soil” further away, the rhizosphere has significantly higher microbial activity and nutrient density, making it a hotspot of life and interaction.

How do root exudates influence the rhizosphere’s environment and its microbial communities?

Root exudates are a complex mixture of organic molecules—including carbohydrates, amino acids, proteins, vitamins, lipids, enzymes, and inorganic ions—secreted by plant roots. These exudates act as vital signaling messengers, shaping the biological, physical, and chemical properties of the rhizosphere. They serve as a food source, attracting and stimulating a diverse array of microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and nematodes, leading to increased microbial activity and population density. The specific composition and quantity of these exudates can vary depending on the plant species, its developmental stage, and environmental conditions (e.g., drought, nutrient deficiency), allowing plants to “select” for beneficial microbial communities while deterring harmful ones.

What are the key roles of microorganisms in the rhizosphere for plant health and soil sustainability?

Microorganisms within the rhizosphere, collectively known as the rhizomicrobiome, play crucial roles that are vital for both plant health and broader ecological sustainability. They are instrumental in:

Nutrient Cycling and Acquisition: Microbes convert organic forms of nutrients (like nitrogen and phosphorus) into inorganic, plant-available forms through processes such as nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and organic matter decomposition, significantly enhancing nutrient uptake by plants.

Plant Growth Promotion: Many rhizosphere microorganisms, often referred to as Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) and Fungi (PGPF), produce phytohormones (e.g., auxins, cytokinins, gibberellins) that stimulate root growth and overall plant development.

Disease Suppression and Defense: Beneficial microbes compete with or actively antagonize plant pathogens by producing antimicrobial compounds (antibiotics, lytic enzymes, siderophores) or by inducing systemic resistance in plants, bolstering their innate defense mechanisms.

Soil Structure Improvement: Microbial secretions, such as mucilage and polysaccharides, help bind soil particles into stable aggregates, improving soil aeration, water retention, and overall soil health.

Stress Tolerance: Some microorganisms help plants cope with abiotic stresses like drought, salinity, and heavy metal toxicity by modulating physiological and biochemical changes in the plant, such as inducing antioxidant activity or altering gene expression for stress-responsive pathways.

How do plants and microorganisms communicate within the rhizosphere?

Communication within the rhizosphere is intricate and involves both “inter- or intraspecies” signaling among microorganisms themselves and “interkingdom” signaling between microbes and plants.

Microbe-to-Microbe Signaling: Microorganisms use chemical signals, particularly through “quorum sensing” (QS) mechanisms, to coordinate their activities based on cell density. These signals (e.g., N-acyl homoserine lactones or AHLs in Gram-negative bacteria, autoinducer peptides in Gram-positive bacteria) regulate processes like biofilm formation, virulence, and metabolism. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) also facilitate long-distance communication among microbial communities.

Microbe-to-Plant Signaling: Microbes release signals (e.g., phytohormones, microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) like flagellin and chitin) that are recognized by plant receptors, triggering specific responses that can promote growth or activate defense mechanisms. For instance, bacterial QS signals can influence plant root growth or induce innate immunity.

Plant-to-Microbe Signaling: Plants actively shape their rhizomicrobiome by secreting specific root exudates that attract beneficial microbes while deterring harmful ones. For example, legumes release flavonoids to attract nitrogen-fixing rhizobia, initiating nodule formation. Plants can also produce VOCs that influence microbial activity and colonization. This complex “crosstalk” allows for tailored interactions beneficial to the plant.

What is “rhizosphere priming” and how does it relate to nutrient availability?

Rhizosphere priming refers to the change in the decomposition of soil organic matter (SOM) caused by plant root activity, often associated with root exudation (rhizodeposition). This effect can be positive (increased SOM decomposition) or negative (decreased SOM decomposition). Its direction and magnitude are significantly influenced by soil nutrient availability, particularly nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P).

N Limitation: In soils with low N availability, root exudates might be used by microbes to “mine” for N locked in SOM, leading to positive priming and enhanced N release through oxidation of SOM. This helps supply N to the plant.

P Limitation: In contrast, under P limitation, root exudates might be used by microbes primarily to mobilize P from inorganic or organic sources (e.g., by producing phosphatase enzymes) rather than enhancing SOM decomposition. This process often does not result in significant rhizosphere priming.

This suggests that plants strategically allocate carbon through exudates to acquire the most limiting nutrient, with different nutrient limitations leading to different rhizosphere priming outcomes.

How is the rhizosphere influenced by climate change, specifically drought conditions?

Climate change, particularly the increased frequency and severity of drought, has significant implications for global agriculture and food security. Drought stress alters the interaction between host plants and their rhizosphere microbiomes. Under water stress, plants exude unique organic molecules into their rhizosphere, changing the microbial community colonizing their roots compared to normal conditions. This shift in exudate composition can lead to changes in the microbial diversity and function within the rhizosphere. Research, such as studies on Fast Plants (Brassica rapa), aims to understand how simulated drought impacts host-microbe interactions to identify novel plant growth-promoting microbes that could help plants adapt to climate change-induced drought. This involves analyzing changes in microbial diversity and taxonomic composition using advanced molecular techniques like DNA sequencing.

What is “rhizosphere engineering” and why is it important for sustainable agriculture?

Rhizosphere engineering refers to the manipulation and management of the rhizosphere’s components—plants, microbes, and soil—to enhance plant productivity and promote ecological sustainability. Given the challenges of global food insecurity, over-reliance on chemical fertilizers, and climate change, rhizosphere engineering offers an eco-friendly approach. It focuses on:

Microbial Inoculation: Introducing beneficial microorganisms (like PGPR) to improve nutrient availability, suppress pathogens, and enhance stress tolerance in plants.

Plant Trait Manipulation: Engineering plants for desired root architecture or exudate profiles that favor beneficial microbial interactions.

Soil Amendments: Modifying soil properties to create more favorable conditions for plant-microbe interactions.

By understanding and manipulating the intricate chemical signaling and interactions within this “root galaxy,” scientists aim to develop sustainable agricultural practices that reduce dependency on synthetic agrochemicals, improve soil health, and enhance crop resilience in a changing environment.

Can the rhizosphere microbial community be studied and manipulated for agricultural benefits?

Yes, the rhizosphere microbial community can be extensively studied and manipulated. Modern research employs advanced molecular techniques such as next-generation DNA sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA V3/V4 Illumina sequencing for bacteria or ITS2 sequencing for fungi) and bioinformatics platforms (like QIIME 2) to analyze microbial diversity, taxonomic composition, and functional characteristics. This allows scientists and students to investigate how factors like drought or specific plant species influence the rhizosphere microbiome.

For agricultural benefits, the rhizosphere microbial community can be manipulated through:

Inoculation: Applying commercial “bio-inoculants” containing beneficial bacteria or fungi (e.g., Rhizobium, Bacillus, Pseudomonas strains) to soils or seeds to boost plant growth, nutrient uptake, and stress tolerance.

Agronomic Practices: Implementing crop rotation and cover cropping, which can leave behind beneficial root remnants and microbes that influence succeeding crops.

Breeding and Genetic Engineering: Selecting or engineering plant genotypes with root traits and exudate compositions that naturally recruit desired microbial communities, leading to more resilient and productive crops.

These efforts are crucial for transitioning towards more sustainable and environmentally friendly agricultural systems

- Kennedy, A. C., & de Luna, L. Z. (2005). RHIZOSPHERE. Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment, 399–406. doi:10.1016/b0-12-348530-4/00163-6

- Dazzo, F. B., & Ganter, S. (2009). Rhizosphere. Encyclopedia of Microbiology, 335–349. doi:10.1016/b978-012373944-5.00287-x

- Broeckling, C. D., Manter, D. K., Paschke, M. W., & Vivanco, J. M. (2008). Rhizosphere Ecology. Encyclopedia of Ecology, 3030–3035. doi:10.1016/b978-008045405-4.00540-1

- Koo, B.-. J., Adriano, D. C., Bolan, N. S., & Barton, C. D. (2005). ROOT EXUDATES AND MICROORGANISMS. Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment, 421–428. doi:10.1016/b0-12-348530-4/00461-6

- Mendes, R., Garbeva, P., & Raaijmakers, J. M. (2013). The rhizosphere microbiome: significance of plant beneficial, plant pathogenic, and human pathogenic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 37(5), 634–663. doi:10.1111/1574-6976.12028

- Huang, X.-F., Chaparro, J. M., Reardon, K. F., Zhang, R., Shen, Q., & Vivanco, J. M. (2014). Rhizosphere interactions: root exudates, microbes, and microbial communities. Botany, 92(4), 267–275. doi:10.1139/cjb-2013-0225

- Dotaniya, M. & Meena, Vasudev. (2015). Rhizosphere Effect on Nutrient Availability in Soil and Its Uptake by Plants: A Review. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences. 85. 10.1007/s40011-013-0297-0.

- Qu, Q., Zhang, Z., Peijnenburg, W. J. G. M., Liu, W., Lu, T., Hu, B., … Qian, H. (2020). Rhizosphere microbiome assemble and its impact on plant growth. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00073

- https://css.wsu.edu/research/rhizosphere/

- https://www.scimagojr.com/journalsearch.php?q=21100788801&tip=sid&clean=0

- https://biologyreader.com/rhizosphere.html

- https://www.slideshare.net/narpatsingh13/rhizosphere

- https://popups.uliege.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=7578

- https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/agriculture-and-human-health/107882/

- https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Rhizosphere_Interactions

- https://microbenotes.com/rhizospheric-microorganisms/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhizosphere