What is replicative transposition?

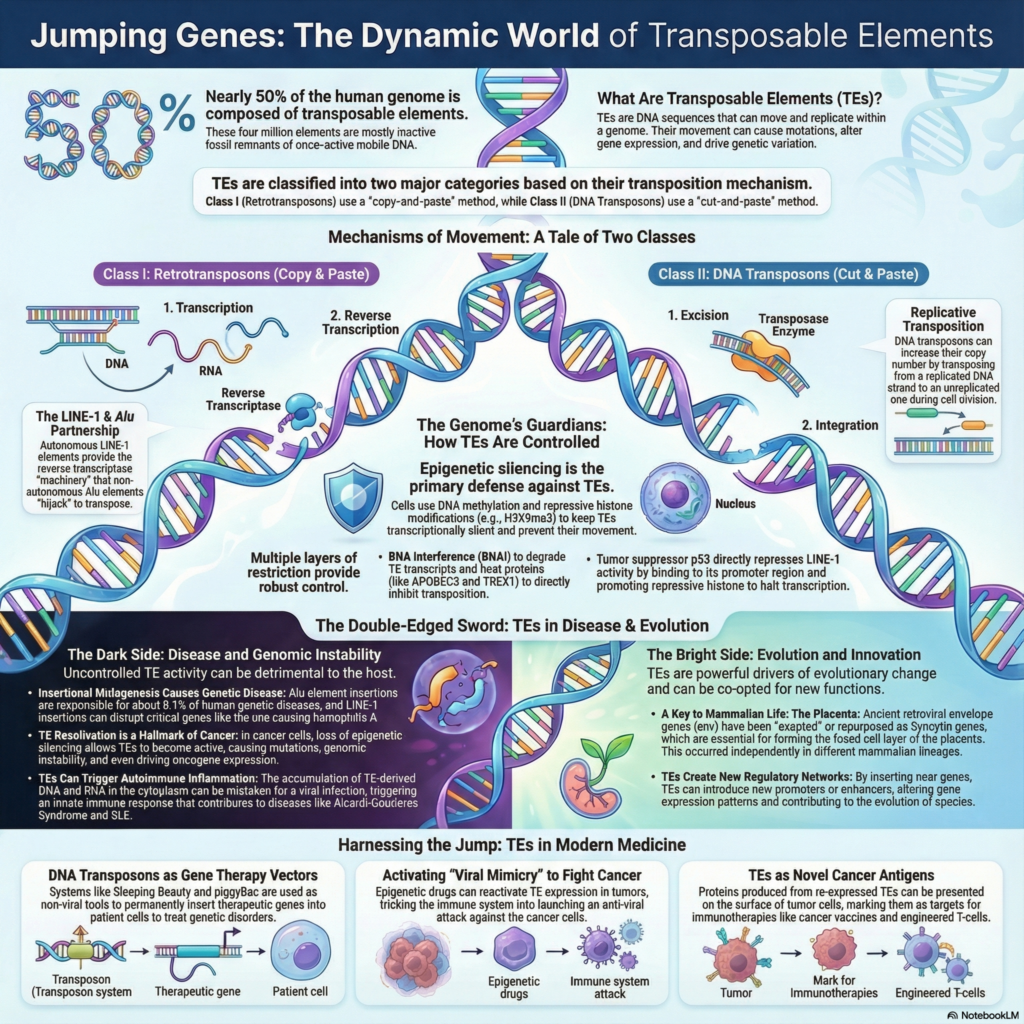

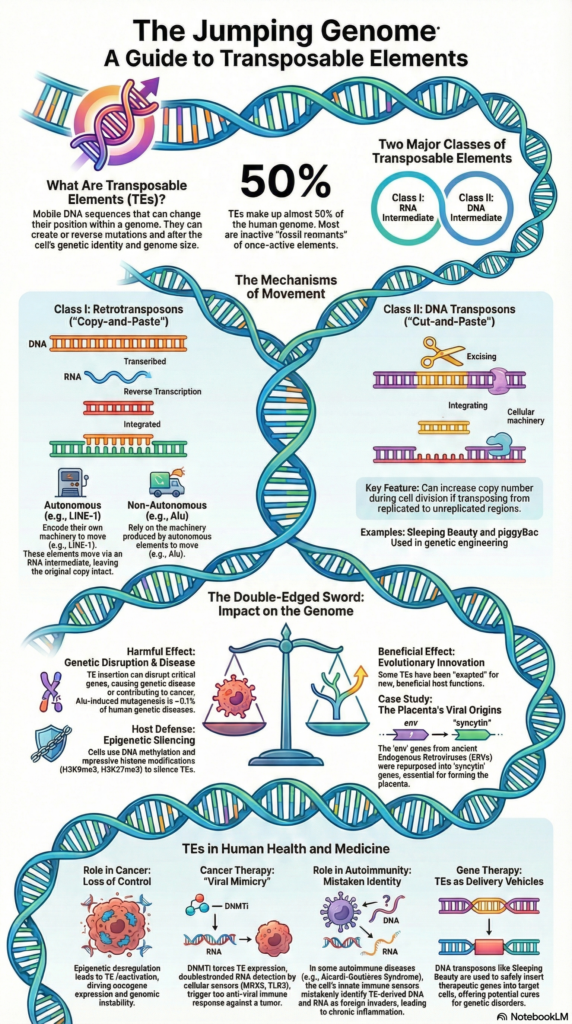

Replicative transposition is a type of transposition in which the transposable element is duplicated during its movement from one site to another. It is the process where the original transposable element remains at the donor site and a new copy is inserted into the target DNA. This is referred to as copy-and-paste mechanism of transposition.

In this process the transposon DNA is not excised completely, instead a replication of the element occurs simultaneously with its integration at the new site. In bacterial DNA transposons like Tn3 family and bacteriophage Mu, a fused DNA structure called cointegrate is formed between donor and target DNA which contains two copies of the transposable element.

This cointegrate structure is later resolved into two separate DNA molecules by specific recombination enzymes. In eukaryotes, retrotransposons also follow replicative transposition where DNA is first transcribed into RNA and then reverse transcribed into DNA before integration. As a result of replicative transposition the copy number of transposable element is increased in the genome.

Replicative transposition of DNA transposons

Step 1. Assembly and nicking

In this step the transposase enzyme binds to the specific inverted repeat sequences present at the two ends of the DNA transposon. It is the process where a synaptic complex is formed by bringing both ends of the transposon close together. The transposase does not excise the transposon completely from donor DNA. Instead single-strand nicks are made at the 3′ ends of the transposon. As a result free 3′-OH groups are exposed while the 5′ ends remain attached to the donor DNA molecule.

Step 2. Strand transfer (Shapiro intermediate formation)

After nicking the transposase captures the target DNA molecule. The exposed 3′-OH ends of the transposon attack the phosphodiester bonds of the target DNA. This reaction joins the ends of the transposon to the target DNA. Since the 5′ ends are still attached to donor DNA a fused branched DNA structure is formed. This structure is referred to as Shapiro intermediate where donor and target DNA molecules become physically connected.

Step 3. Replication and cointegrate formation

In this step the host cell replication machinery is assembled at the fork-like junctions of the Shapiro intermediate. DNA polymerase uses the 3′ ends as primers and replication proceeds through the entire transposon sequence. Due to this replication two copies of the transposon is produced. The final structure formed is called cointegrate which contains both donor and target DNA molecules joined together and separated by two directly repeated copies of the transposon.

Step 4. Resolution of cointegrate

To separate the fused DNA molecules a site-specific recombination event occurs between the two copies of the transposon. Many replicative transposons encode an enzyme called resolvase. This enzyme recognizes a specific internal site known as res site. The resolvase catalyzes recombination between the two res sites leading to resolution of cointegrate. As a result two separate DNA molecules are formed, one donor DNA retaining original transposon and one target DNA carrying newly inserted transposon.

Step 5. Final repair

After resolution short single-stranded gaps remain at the site of insertion in target DNA. These gaps are filled by host DNA polymerase and sealed by DNA ligase. This process results in the formation of short target site duplications flanking the inserted transposon. Thus replicative transposition leads to increase in copy number of DNA transposons.

Replicative transposition of retrotransposons

Step 1. Transcription

The process begins in nucleus where the DNA sequence of retrotransposon is transcribed by cellular RNA polymerase. It is the process in which a single-stranded RNA molecule is synthesized from retrotransposon DNA. This RNA acts as an intermediate and the original retrotransposon remains at its genomic position. The newly formed RNA transcript is then transported from nucleus to cytoplasm.

Step 2. Translation and RNP formation

In cytoplasm the retrotransposon RNA is translated to produce required proteins. These proteins mainly include RNA-binding protein and reverse transcriptase containing endonuclease activity. The synthesized proteins bind back to the same RNA molecule. This association forms a ribonucleoprotein complex. This complex is essential for further steps of transposition.

Step 3. Target site cleavage

The ribonucleoprotein complex re-enters nucleus and searches for a suitable target site in genomic DNA. The endonuclease activity present in the protein nicks one strand of target DNA. This cleavage occurs at a specific consensus sequence. As a result a free 3′-OH group is generated at the target site which acts as primer for DNA synthesis.

Step 4. Reverse transcription

In this step the free 3′-OH group of target DNA is used as primer by reverse transcriptase enzyme. The retrotransposon RNA serves as template. Using this RNA template the enzyme synthesizes the first strand of complementary DNA directly at the target site. This process is referred to as target-primed reverse transcription.

Step 5. Second strand synthesis and integration

After first strand synthesis the second strand of target DNA is cleaved. The second DNA strand of retrotransposon is synthesized and integrated into the host genome. The exact sequence of cleavage and synthesis may vary but finally a double-stranded DNA copy of retrotransposon becomes inserted at new genomic location.

Step 6. DNA repair and target site duplication

Following integration small single-stranded gaps remain at the insertion site. These gaps are repaired by host DNA polymerase and ligase enzymes. During this repair short repeated sequences known as target site duplications are formed on both sides of inserted retrotransposon. Thus replicative transposition of retrotransposons results in increase in copy number within genome.

Comparison between transposase and resolvase in transposition

1. Role in transposition process

- Transposase – It is the enzyme that initiates the process of transposition. It catalyzes the fusion of donor DNA containing the transposon with the target DNA molecule. This step results in formation of cointegrate structure during replicative transposition.

- Resolvase – It functions in the later stage of transposition. It resolves the cointegrate intermediate and separates the fused DNA molecules into two independent replicons each carrying one copy of transposon.

2. DNA binding site

- Transposase – It binds to the terminal inverted repeat sequences present at the ends of the transposon. These repeats are required for recognition and movement of the transposon.

- Resolvase – It binds to a specific internal DNA sequence known as resolution site (res site). This site is located within the transposon and is essential for recombination.

3. Enzymatic activity

- Transposase – It introduces single-strand nicks at the ends of transposon and mediates strand transfer reaction. This activity initiates DNA replication leading to duplication of transposon.

- Resolvase – It acts as a site-specific recombinase. It catalyzes breaking and rejoining of DNA strands at res site to resolve the cointegrate.

4. Outcome of action

- Transposase – Its action leads to formation of cointegrate molecule in which donor and target DNA are fused together with two copies of transposon.

- Resolvase – Its action leads to separation of donor and target DNA molecules resulting in stable insertion of transposon.

5. Regulatory role

- Transposase – It mainly functions as catalytic enzyme for transposition and does not have regulatory role.

- Resolvase – Along with recombination it also acts as transcriptional repressor. It controls expression of both transposase and resolvase genes and helps in maintaining stability of transposon.

| Feature | Transposase | Resolvase |

|---|---|---|

| Main role | It initiates the process of transposition | It resolves the cointegrate formed during transposition |

| Stage of action | Acts in early stage of replicative transposition | Acts in later stage after cointegrate formation |

| DNA binding site | Binds to terminal inverted repeats present at ends of transposon | Binds to internal resolution site (res site) |

| Enzymatic function | Makes single-strand nicks and mediates strand transfer | Catalyzes site-specific recombination |

| Structure formed | Leads to formation of cointegrate molecule | Separates cointegrate into two DNA molecules |

| Effect on DNA | Fuses donor and target DNA with duplicated transposon | Produces stable donor and target DNA each with one copy |

| Regulatory role | Mainly catalytic with no regulatory function | Also acts as transcriptional repressor controlling gene expression |

How does the DDE transposase catalyze the strand transfer reaction?

The DDE transposase catalyzes the strand transfer reaction through a conserved chemical mechanism that involves metal ion coordination and nucleophilic attack. The enzyme contains a characteristic catalytic triad composed of two aspartate (D) residues and one glutamate (E) residue. These acidic amino acids form the active site of the enzyme and coordinate divalent metal ions such as Mg²⁺ or Mn²⁺. The bound metal ions are essential as they activate the reacting groups and stabilize the negative charges that develop during phosphodiester bond cleavage.

In the first part of the reaction the transposase catalyzes a single-strand cleavage at the ends of the transposon. A water molecule is activated by the coordinated metal ions and acts as a nucleophile. This water attacks the phosphodiester bond at the 3′ end of the transposon DNA. As a result the DNA strand is nicked and a free 3′-hydroxyl (3′-OH) group is generated at each end of the transposon. This step does not involve formation of a covalent protein-DNA intermediate.

In the second part of the reaction the exposed 3′-OH groups serve as nucleophiles for strand transfer. These hydroxyl groups directly attack specific phosphodiester bonds in the target DNA. The reaction occurs as a one-step transesterification where the energy of the broken bond is conserved to form a new bond. The 3′ ends of the transposon become covalently joined to the 5′ phosphate groups of the target DNA without requirement of ATP.

During this process the transposase complex positions the transposon ends and target DNA in an optimal geometry. The target DNA is cleaved in a staggered manner, producing short single-stranded gaps at the insertion site. The transposase often induces bending of the target DNA which helps align the phosphodiester bonds for efficient nucleophilic attack. After strand transfer these gaps are later repaired by host enzymes, resulting in formation of target site duplications flanking the inserted transposon.

Role of host DNA replication in transposon copy duplication

- Recruitment of host replication machinery– In replicative transposition the transposase forms a branched DNA structure between donor and target DNA. This structure acts as a signal for host replication proteins. The host replisome is assembled at this site and DNA polymerase replicates through the entire transposon sequence. As a result two copies of transposon are produced in the fused DNA molecule.

- Replication of cointegrate intermediate– The cointegrate formed during replicative transposition serves as a template for host DNA replication. Host DNA polymerase extends from the available 3′ ends and duplicates the transposon while copying surrounding DNA. This replication step is responsible for increasing the copy number of transposon.

- Coupling with reverse transcription in retrotransposons– In retrotransposons the host replication factors assist during target-primed reverse transcription. Host proteins stabilize the replication complex at target DNA and help in completion of cDNA synthesis. This cooperation allows formation of a new DNA copy without removal of original element.

- Repair and gap filling at insertion site– After integration of transposon short single-stranded gaps remain at target site. Host DNA polymerase fills these gaps and DNA ligase seals the strands. This localized DNA synthesis results in formation of target site duplications flanking the transposon.

- Use of replication timing for duplication -Some transposons exploit host DNA replication timing. When transposition occurs after donor site replication and before target site replication the host repair system restores the original copy while a new copy integrates elsewhere. This leads to net duplication of transposon copy number.

Comparison between transposase and resolvase in transposition

- Role in transposition process

- Transposase – It initiates the process of transposition. It is responsible for early events that lead to movement of transposon DNA.

- Resolvase – It acts at the later stage of transposition. It functions after formation of the intermediate structure.

- Stage of action

- Transposase – Acts during initiation and cointegrate formation stage of replicative transposition.

- Resolvase – Acts during resolution stage to complete the transposition process.

- DNA binding site

- Transposase – Binds to inverted repeat sequences present at the two ends of the transposon.

- Resolvase – Binds to an internal resolution site (res site) located within the transposon.

- Catalytic activity

- Transposase – Catalyzes single-strand cleavage and strand transfer reaction which joins transposon ends to target DNA.

- Resolvase – Catalyzes site-specific recombination between two res sites in the cointegrate.

- Structure formed or processed

- Transposase – Leads to formation of cointegrate structure where donor and target DNA are fused and transposon is duplicated.

- Resolvase – Resolves the cointegrate into two separate DNA molecules.

- Final outcome

- Transposase – Produces fused donor and target DNA containing two copies of transposon.

- Resolvase – Produces stable donor and target DNA each carrying one copy of transposon.

- Regulatory role

- Transposase – Mainly functions as catalytic enzyme and has no major regulatory role.

- Resolvase – Also acts as transcriptional repressor controlling expression of transposase and resolvase genes.

- Akhverdyan, V. Z., Gak, E. R., Tokmakova, I. L., Stoynova, N. V., Yomantas, Y. A. V., & Mashko, S. V. (2011). Application of the bacteriophage Mu-driven system for the integration/amplification of target genes in the chromosomes of engineered Gram-negative bacteria—mini review. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 91(4), 857–871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-011-3416-y

- Au, T. K., Agrawal, P., & Harshey, R. M. (2006). Chromosomal integration mechanism of infecting Mu virion DNA. Journal of Bacteriology, 188(5), 1829–1834. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.188.5.1829-1834.2006

- Baidya, D. (2019, May 13). Replicative Transposition of DNA transposons and Retrotransposons. Genetic Education. https://geneticeducation.co.in/replicative-transposition-of-dna-transposons-and-retrotransposons/

- Beauregard, A., Curcio, M. J., & Belfort, M. (2008). The take and give between retrotransposable elements and their hosts. Annual Review of Genetics, 42, 587–617.

- Beck, C. R., Garcia-Perez, J. L., Badge, R. M., & Moran, J. V. (2011). LINE-1 elements in structural variation and disease. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 12, 187–215. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141802

- Bergtrom, G. (2021, January 3). 14.4: Transposons Since McClintock. Biology LibreTexts. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Basic_Cell_and_Molecular_Biology_(Bergtrom)/14%3A_Repetitive_DNA_A_Eukaryotic_Genomic_Phenomenon/14.04%3A_Transposons_Since_McClintock

- Biotech Review. (n.d.). Alu Insertion Polymorphism | SINEs | LINEs | How Alu element Transposes | How Alu Jumps | L1 element [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zFV8dO3YQX0

- Boundless. (2023, September 13). 4.7.5: Mu- A Double-Stranded Transposable DNA Bacteriophage. Biology LibreTexts. https://bio.libretexts.org/Courses/Northwest_University/MKBN211%3A_Introductory_Microbiology_(Bezuidenhout)/04%3A_Viruses/4.07%3A_Viral_Diversity/4.7.05%3A_Mu-_A_Double-Stranded_Transposable_DNA_Bacteriophage

- Chen, J.-M., Férec, C., & Cooper, D. N. (2007). Mechanism of Alu integration into the human genome. Current Genomics, 1(1-2), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11568-007-9002-9

- Chuong, E. B., Elde, N. C., & Feschotte, C. (2016). Regulatory activities of transposable elements: From conflicts to benefits. Nature Reviews Genetics, 18(2), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.139

- Cordaux, R., & Batzer, M. A. (2009). The impact of retrotransposons on human genome evolution. Nature Reviews Genetics, 10(10), 691–703. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2640

Czech, B., Munafò, M., Ciabrelli, F., Eastwood, E. L., Fabry, M. H., Kneuss, E., & Hannon, G. J. (2018). piRNA-guided genome defense: From biogenesis to silencing. Annual Review of Genetics, 52, 131–157. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-120417-031441 - Davis, R., Shaban, N. M., Perrino, F. W., & Hollis, T. (2015). Crystal structure of RNA-DNA duplex provides insight into conformational changes induced by RNase H binding. ResearchGate.

- de Souza, F. S. J., Franchini, L. F., & Rubinstein, M. (2013). Exaptation of transposable elements into novel cis-regulatory elements: Is the evidence always strong? Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30(6), 1239–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst045

- Feschotte, C. (2008). The contribution of transposable elements to the evolution of regulatory networks. Nature Reviews Genetics, 9(5), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2337

- Fuller, J. R., & Rice, P. A. (2017). Target DNA bending by the Mu transpososome promotes careful transposition and prevents its reversal. eLife, 6, e21777. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.21777

- Ghanim, G. E., Hu, H., Boulanger, J., & Nguyen, T. H. D. (2025). Structural mechanism of LINE-1 target-primed reverse transcription. Science, 388(6745), eads8412. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ads8412

- Grindley, N. D. F. (2002). The movement of Tn3-like elements: Transposition and cointegrate resolution. In Mobile DNA II (pp. 272–302). ASM Press. https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555817954.ch14

- Grundy, E. E., Diab, N., & Chiappinelli, K. B. (2021). Transposable element regulation and expression in cancer. The FEBS Journal, 289(5), 1160–1179. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15722

- Hallet, B., & Sherratt, D. J. (1997). Transposition and site-specific recombination: Adapting DNA cut-and-paste mechanisms to a variety of genetic rearrangements. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 21(2), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00349.x

- Hamperl, S., & Cimprich, K. A. (2014). The contribution of co-transcriptional RNA:DNA hybrid structures to DNA damage and genome instability. DNA Repair, 19, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.023

- Han, J. S. (2010). Non-long terminal repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposons: Mechanisms, recent developments, and unanswered questions. Mobile DNA, 1(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1759-8753-1-15

- Harshey, R. M. (2014). Transposable phage Mu. Microbiology Spectrum, 2(5). https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0007-2014

- He, S., Hickman, A. B., Varani, A. M., Siguier, P., Chandler, M., Dekker, J. P., & Dyda, F. (2015). Insertion Sequence IS26 reorganizes plasmids in clinically isolated multidrug-resistant bacteria by replicative transposition. mBio, 6(3), e00762-15. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00762-15

- Jang, S., & Harshey, R. M. (2015). Repair of transposable phage Mu DNA insertions begins only when the E. coli replisome collides with the transpososome. Molecular Microbiology, 97(4), 746–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/mmi.13061

- Jang, S., Sandler, S. J., & Harshey, R. M. (2012). Mu insertions are repaired by the double-strand break repair pathway of Escherichia coli. PLoS Genetics, 8(4), e1002642. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002642

- Kojima, K. K. (2019). Structural and sequence diversity of eukaryotic transposable elements. Genes & Genetic Systems, 94(6), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1266/ggs.18-00024

- Ladd, M., & Bordoni, B. (2023, April 10). Genetics, Transposons. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557780/

- Lagisquet, J., Zuber, K., & Gramberg, T. (2021). Recognize Yourself—Innate sensing of non-LTR retrotransposons. Viruses, 13(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13010094

- Lavialle, C., Cornelis, G., Dupressoir, A., Esnault, C., Heidmann, O., Vernochet, C., & Heidmann, T. (2013). Paleovirology of ‘syncytins’, retroviral env genes exapted for a role in placentation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1626), 20120507. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0507

- Liang, Z., Jia, C., Yao, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Epigenetic control of transposable elements. In Transposable Elements, Transcriptomics, and Diseases (pp. 109–151). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-032-04125-8_4

- Lima-Mendez, G., Alvarenga, D. O., Ross, K., Hallet, B., Van Melderen, L., Varani, A. M., & Chandler, M. (2020). Toxin-antitoxin gene pairs found in Tn3 family transposons appear to be an integral part of the transposition module. mBio, 11(2), e00452-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00452-20

- Liu, J.-H., Xi, K., Zhang, X., Bao, L., Zhang, X., & Tan, Z.-J. (2019). Structural flexibility of DNA-RNA hybrid duplex: Stretching and twist-stretch coupling. Biophysical Journal, 117(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.05.018

- Ninova, M., Fejes Tóth, K., & Aravin, A. A. (2019). The control of gene expression and cell identity by H3K9 trimethylation. Development, 146(19), dev181180. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.181180

- Nowak, E., Miller, J. T., Bona, M. K., Studnicka, J., Szczepanowski, R. H., Jurkowski, J., Le Grice, S. F. J., & Nowotny, M. (2014). Ty3 reverse transcriptase complexed with an RNA-DNA hybrid shows structural and functional asymmetry. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 21(4), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2785

- Pearson. (n.d.). Compare DNA transposons and retrotransposons. What properties do they share? Pearson. https://www.pearson.com/channels/genetics/asset/2f49fe8b/compare-dna-transposons-and-retrotransposons-what-properties-do-they-share

- Petroll, R., Papareddy, R. K., Krela, R., Laigle, A., Rivière, Q., Bišova, K., Mozgová, I., & Borg, M. (2025). The expansion and diversification of epigenetic regulatory networks underpins major transitions in the evolution of land plants. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 42(4), msaf064. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaf064

- Reich, C., Waggoner, B. T., & Pato, M. L. (1984). Synchronization of bacteriophage Mu DNA replicative transposition: Analysis of the first round after induction. The EMBO Journal, 3(7), 1507–1511. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02003.x

- Richardson, S. R., Doucet, A. J., Kopera, H. C., Moldovan, J. B., Garcia-Pérez, J. L., & Moran, J. V. (2015). The influence of LINE-1 and SINE retrotransposons on mammalian genomes. Microbiology Spectrum, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0061-2014

- Rivkaie, G. (2024). Mechanisms of epigenetic regulation: Roles of RNA and DNA methylation. Journal of Molecular Pathology and Biochemistry, 5(3), 193. https://doi.org/10.35248/jmpb.24.5.193

- Sakurai, T., Kusama, K., & Imakawa, K. (2023). Progressive exaptation of endogenous retroviruses in placental evolution in cattle. Biomolecules, 13(12), 1680. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13121680

- Shimode, S. (2023). Acquisition and exaptation of endogenous retroviruses in mammalian placenta. Biomolecules, 13(10), 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13101482

- Shivaji College. (n.d.). Transposing elements.pdf. https://www.shivajicollege.ac.in/Study/transposing%20elements%20.pdf

- Skipper, K. A., Andersen, P. R., Sharma, N., & Mikkelsen, J. G. (2013). DNA transposon-based gene vehicles – scenes from an evolutionary drive. Journal of Biomedical Science, 20(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/1423-0127-20-92

- Snowbarger, J., Koganti, P., & Spruck, C. (2024). Evolution of repetitive elements, their roles in homeostasis and human disease, and potential therapeutic applications. Biomolecules, 14(10), 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14101250

- Stenz, L. (2021). The L1-dependant and Pol III transcribed Alu retrotransposon, from its discovery to innate immunity. Molecular Biology Reports, 48(3), 2775–2789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-021-06258-4

- Tóth, K. F., Pezic, D., Stuwe, E., & Webster, A. (2016). The piRNA pathway guards the germline genome against transposable elements. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 886, 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7417-8_4

- UK Essays. (2018, November). Mechanisms Of Conservative And Replicative Transposition Biology Essay. UKEssays.com. https://www.ukessays.com/essays/biology/mechanisms-of-conservative-and-replicative-transposition-biology-essay.php

- Wagstaff, B. J., Hedges, D. J., Derbes, R. S., Campos-Sánchez, R., Chiaromonte, F., Makova, K. D., & Roy-Engel, A. M. (2012). Rescuing Alu: Recovery of new inserts shows LINE-1 preserves Alu activity through A-tail expansion. PLoS Genetics, 8(8), e1002842. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002842

- Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Tn3 transposon. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tn3_transposon

- Zaratiegui, M. (2017). Cross-regulation between transposable elements and host DNA replication. Viruses, 9(3), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/v9030057