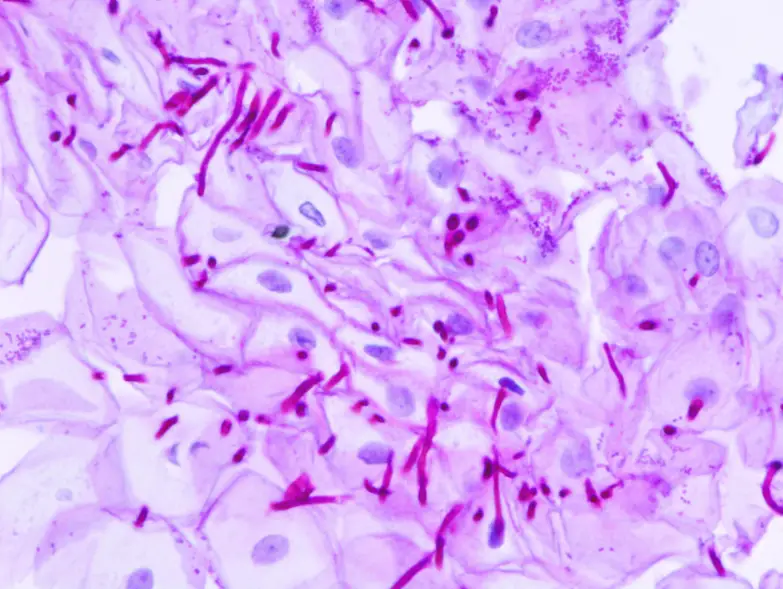

Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining is a histochemical method used to demonstrate carbohydrate and carbohydrate-rich compounds in tissue sections. It is the process where periodic acid is used to oxidize the 1,2-glycol groups of polysaccharides, mucin, glycogen and fungal cell wall components into aldehyde groups. These aldehydes then react with Schiff’s reagent to produce a characteristic magenta colour. It is the technique commonly applied in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections and also in frozen tissues. The reaction is as follows– periodic acid first creates reactive aldehydes, and Schiff reagent condenses with these aldehydes to form a stable coloured product. It is usually counterstained with hematoxylin so the nucleus appears blue while the PAS-positive structures appear pink to purple.

It is the method used in detecting glycogen in skeletal muscles, liver and cardiac muscles. This process occurs when the tissues contain carbohydrate-rich macromolecules which is oxidized by periodic acid and then visualized after Schiff’s reagent treatment. Basement membranes, neutral mucins and fungal cell wall elements are also demonstrated clearly by this technique. Among the important diagnostic uses, PAS stain helps in renal pathology to highlight the glomerular basement membrane and tubular structures, and it is also used in identifying fungal infections such as Candida or Aspergillus.

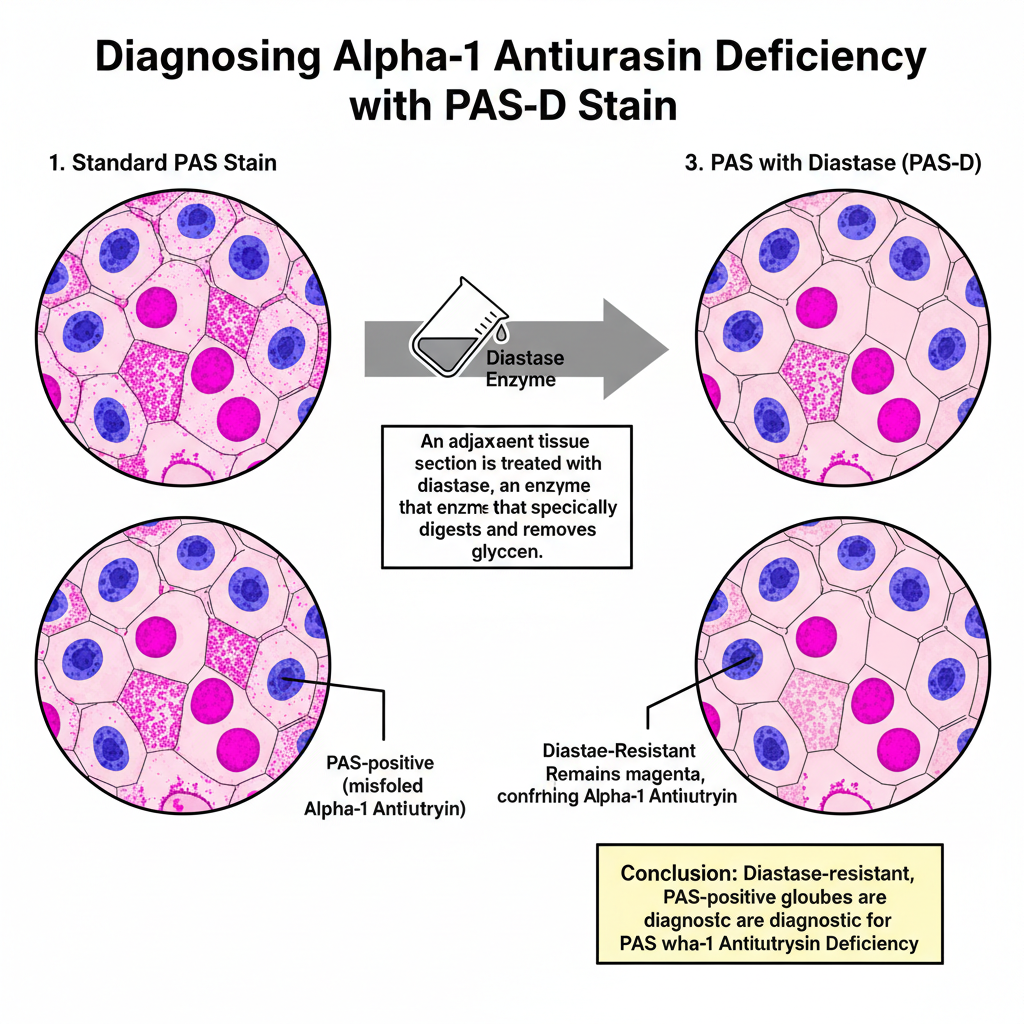

In some cases, modifications like PAS-diastase (PAS-D) are used, where diastase digest the glycogen before staining. This helps in confirming the presence of true glycogen because the glycogen disappears after digestion while other PAS-positive materials remain. It is also combined with Alcian Blue in AB-PAS staining to distinguish acidic and neutral mucins, where acidic mucins appear blue and neutral mucins appear magenta. It is the process dependent on proper preparation of Schiff’s reagent as any discoloration can cause background staining. Fixatives like glutaraldehyde may create free aldehyde groups and lead to false-positive reactions unless removed or blocked properly. When the procedure is carried out correctly, PAS staining is useful for demonstrating tissue structures, metabolic disorders and fungal organisms.

Principle of Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

The principle of Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining is based on the oxidation of carbohydrate-rich molecules to produce reactive aldehyde groups which then react with Schiff’s reagent. It is the process where periodic acid acts as an oxidizing agent and cleaves the carbon–carbon bond of the 1,2-glycol groups (vicinal diols) present in polysaccharides, glycoproteins and neutral mucosubstances. This oxidation produces dialdehyde groups in the tissue without affecting other chemical structures. When Schiff’s reagent is applied, it combines with these aldehydes forming a stable coloured compound which appears magenta. The reaction is referred to as the PAS reaction, and the colour formation depends on the presence and concentration of these glycol groups.

In this step, Schiff’s reagent which is colourless due to its reduction with sulfurous acid, reacts immediately with the aldehydes, and after washing in water the final colour develops. The washing step is essential as it removes excess reagent and allows the quinoid structure to form completely. It is the process responsible for giving magenta colour to glycogen, basement membranes, fungal cell walls and neutral mucins, while the nuclei are seen blue when counterstained with hematoxylin. Thus, PAS staining principle depends on the oxidation–aldehyde formation–Schiff reaction sequence which highlights carbohydrate-containing structures in tissues.

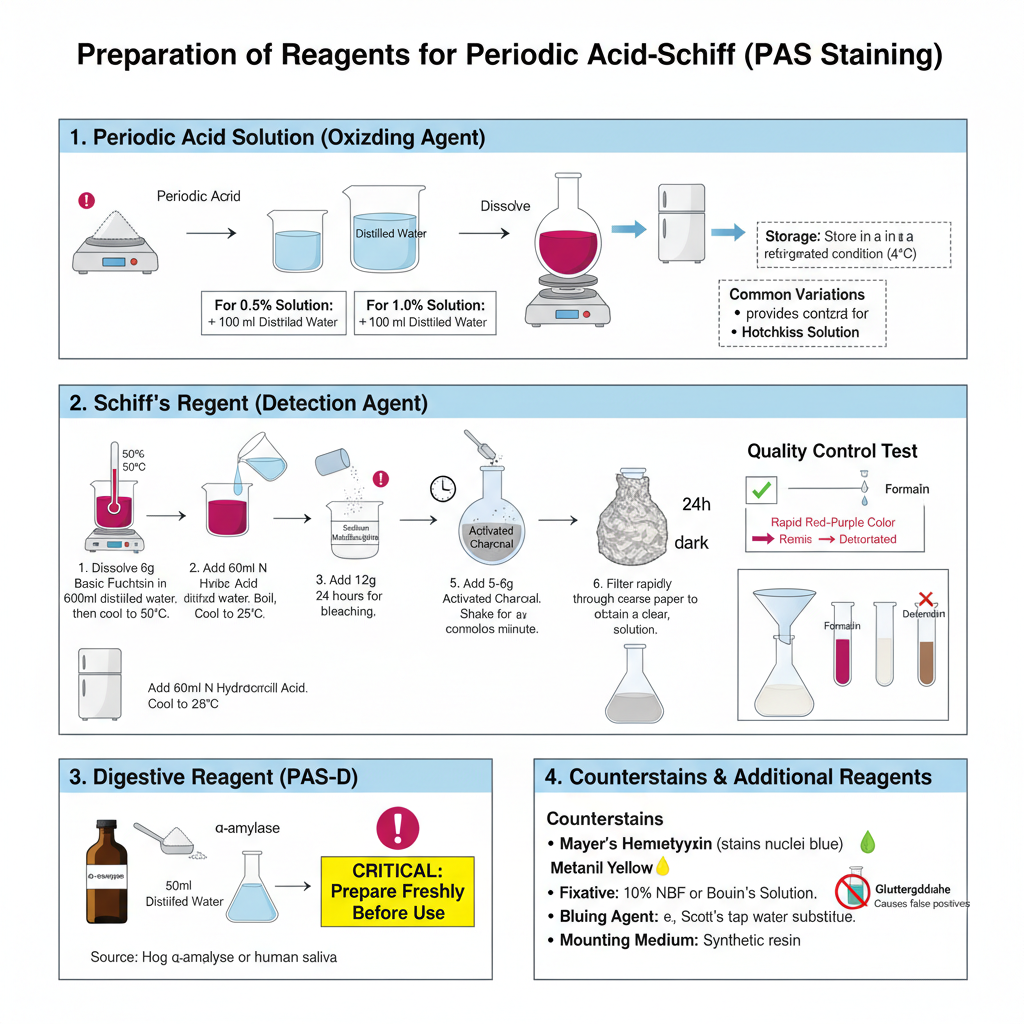

Preparation of Solutions and Reagents for Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

- Periodic Acid Solution (Oxidizing Agent)

- It is the solution used to oxidize 1,2-glycol groups into aldehyde groups.

- A 0.5% or 1.0% aqueous solution is commonly used in the staining process.

- For 0.5% preparation, 0.5 g of periodic acid is dissolved in 100 ml distilled water. It is also prepared by dissolving 2.5 g periodic acid in 500 ml water.

- The solution is stored in refrigerated condition.

- Some of the variations are Lillie’s solution (using sodium iodate or potassium iodate in nitric acid) and Hotchkiss solution (periodic acid in sodium acetate and ethanol).

- Schiff’s Reagent (Detection Agent)

- It is the reagent that reacts with aldehyde groups to form the characteristic magenta colour.

- The reagent is made using basic fuchsin dye, hydrochloric acid, and sodium metabisulphite.

- Preparation steps are–

- 6 g basic fuchsin is dissolved in 600 ml distilled water and the mixture is boiled and then cooled to 50°C.

- 60 ml of N hydrochloric acid is added and the mixture is cooled to 25°C.

- 12 g sodium metabisulphite is added after cooling.

- The mixture is kept in dark for 24 hours so that bleaching occurs.

- 5–6 g activated charcoal is added and shaken for about one minute.

- It is filtered rapidly through coarse filter paper to obtain a clear solution.

- The reagent is stored in dark bottle inside refrigerator (2–8°C).

– For testing the reagent quality, a few drops are added to 10 ml of 37% formalin solution. A rapid red-purple colour indicate good reagent while brownish colour indicate deterioration.

- Counterstains

- Mayer’s Hematoxylin is used to stain nuclei blue.

- Light green is preferred in fungal demonstration because it gives better contrast.

- Metanil yellow is also used in some procedures.

- Digestive Reagent (PAS-Diastase / PAS-D)

- It is used for digesting glycogen so that glycogen-positive structures can be differentiated.

- 0.25 g α-amylase (diastase) is dissolved in 50 ml distilled water.

- The solution is freshly prepared before use. Hog α-amylase is generally used, but human saliva may also be used if enzyme is not available.

- Additional Reagents

- Fixatives used are 10% neutral buffered formalin or Bouin solution. Glutaraldehyde is avoided because free aldehyde groups create false PAS positivity.

- Bluing agent such as Scott’s tap water substitute is used after hematoxylin staining.

- Mounting medium used is a synthetic medium for coverslipping.

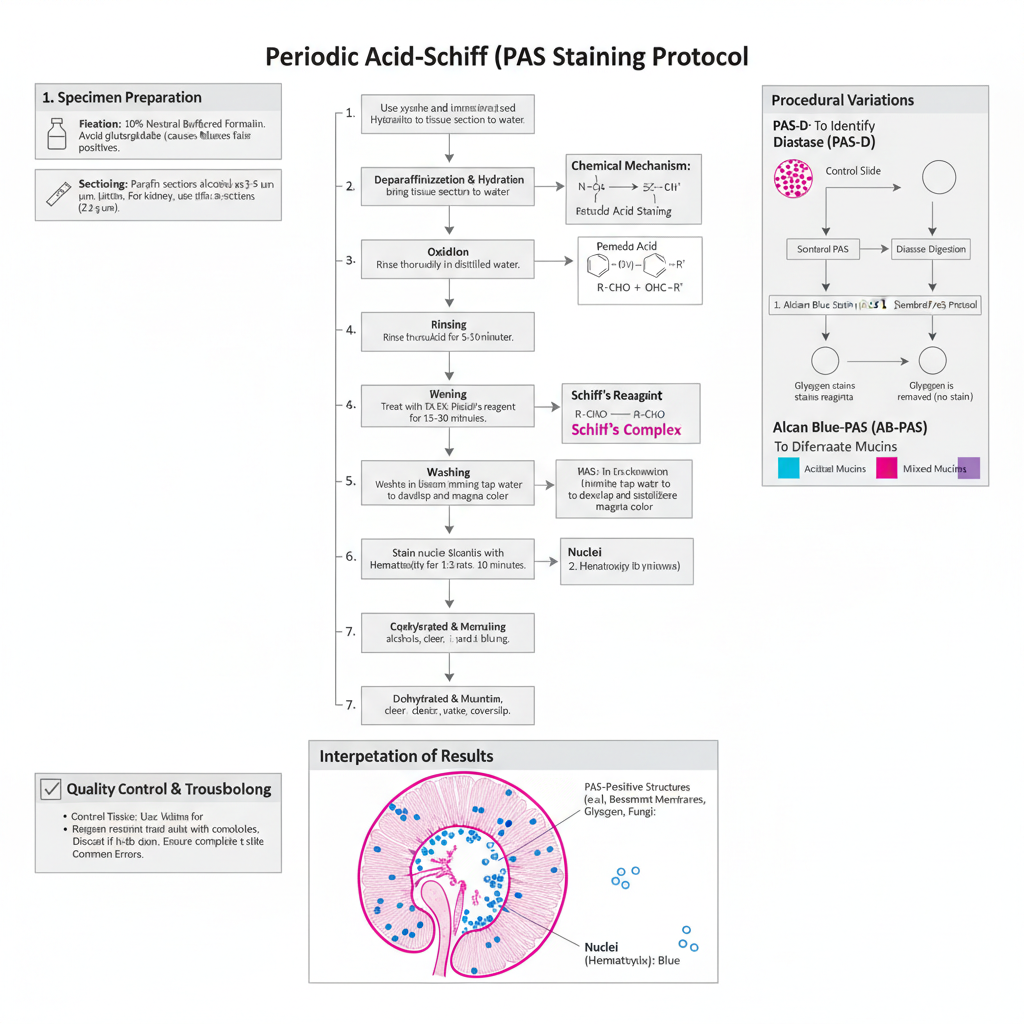

Procedure for Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

- Specimen Preparation and Fixation

- Tissue must be properly fixed before staining. The recommended fixatives are 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) or Bouin solution.

- Glutaraldehyde is avoided as it leaves free aldehyde groups which react with Schiff reagent and produce false positive colour.

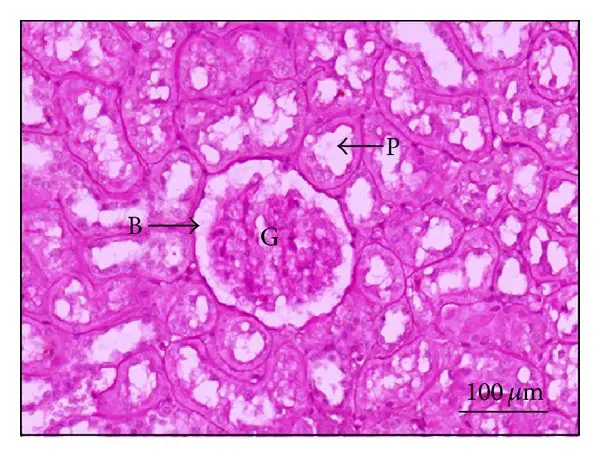

- Paraffin sections are generally cut at 3–5 µm thickness. In renal biopsies the section is made thinner (about 2 µm) for clear view of basement membrane.

- Standard PAS Staining Protocol– The process is based on oxidation of carbohydrate groups by periodic acid followed by reaction of aldehydes with Schiff reagent.

- Step 1: Deparaffinization and Hydration– Sections are deparaffinized in xylene and then rehydrated through descending grades of alcohol to distilled water.

- Step 2: Oxidation (Periodic Acid)

- Sections are treated with 0.5%–1.0% periodic acid.

- Incubation time is around 5–10 minutes at room temperature.

- It is the step where 1,2-glycol groups are oxidized to aldehydes. Short exposure may give weak staining of basement membrane.

- Step 3: Rinsing– The slides are washed well in distilled water to remove all periodic acid.

- Step 4: Schiff Reagent Application– Sections are placed in Schiff reagent for 10–30 minutes and usually 15 minutes is taken as standard time. A light pink colour may appear during this step. It is the colourless reagent that reacts with formed aldehydes to give the magenta colour.

- Step 5: Washing (Critical Step)– Sections are washed in lukewarm running water for about 5–10 minutes. During washing the colour develops into a bright magenta. Insufficient washing can give weak or unstable colour.

- Step 6: Counterstaining– Nuclei are stained with hematoxylin (Mayer or Harris type) for 1–3 minutes. If a regressive hematoxylin is used, then differentiation in acid alcohol and bluing in Scott water is performed. Light green counterstain is used when fungal structures are to be demonstrated.

- Step 7: Dehydration and Mounting– Sections are dehydrated through ascending alcohol grades, cleared in xylene and mounted using synthetic resin.

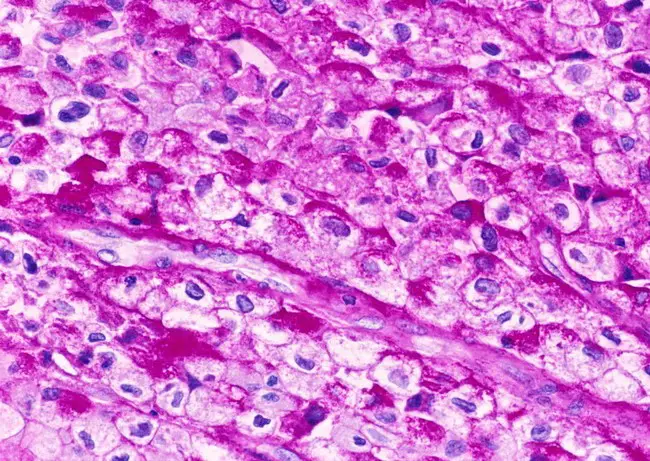

- Interpretation of Results– PAS positive structures appear magenta or red. These include glycogen, neutral mucins, fungal cell wall, and basement membrane. Nuclei appear blue after hematoxylin. Background remains pale or colourless unless a counterstain like light green is used.

- Procedural Variations PAS with Diastase (PAS-D)

- Two slides are used. One slide is treated with diastase or saliva for 20–60 minutes before standard PAS steps.

- Glycogen disappears from the diastase-treated slide but remains magenta in the untreated slide.

- Structures resistant to diastase like alpha-1 antitrypsin globules remain magenta in both slides.

- Alcian Blue–PAS (AB-PAS)

- Sections are first stained with Alcian Blue (pH 2.5).

- Then the normal PAS procedure is performed.

- Acidic mucins appear blue while neutral mucins appear magenta. A mixture shows purple appearance.

- Quality Control and Troubleshooting

- Kidney is used as control tissue because it shows fine basement membrane structure. Liver and cervix can also be used for glycogen and mucins.

- Schiff reagent must be stored cold and protected from light. If it becomes pink in storage it should be discarded as it gives non-specific background.

- Slide orientation must be checked during staining because both periodic acid and Schiff reagent are colourless and slides may be stained in wrong side without noticing.

Results and Interpretation of Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

- General Visual Appearance

- PAS stain produces a magenta or red colour in tissues that contain carbohydrate groups like glycogen, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans.

- The intensity of colour is linked with the amount of reactive 1,2-glycol groups that are present in the section.

- When hematoxylin is used as counterstain the nuclei appear blue or blue-violet giving a clear contrast with the magenta PAS-positive parts.

- If light green counterstain is used the background appears green and fungal elements show magenta colour clearly.

- Erythrocytes mostly remain unstained or show faint pink appearance.

- Interpretation in Different Tissues Liver

- Normal liver shows dark pink cytoplasm because of glycogen presence.

- In Alpha-1 Antitrypsin deficiency there are PAS-positive globules in periportal hepatocytes, representing misfolded protein deposits.

- Kidney– PAS is widely used to observe renal architecture. The glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and tubular epithelium stain strongly. It helps in identifying changes like GBM thickening, hyaline deposits, and segmental sclerosis in diseases such as FSGS and diabetic nephropathy. Very thin sections (around 2 µm) are preferred for these structures.

- Gastrointestinal and Glandular Tissues– Neutral mucins from stomach epithelium, Brunner gland and prostate are stained. PAS positivity is also seen in mucin-secreting adenocarcinomas. PAS-positive macrophages are characteristic in Whipple disease.

- Infectious Diseases– Fungal organisms (Candida, Aspergillus) show strong magenta staining because of polysaccharide-rich cell walls.

- Dermatology and Hematology– PAS positivity along basement membrane zone of the skin can indicate immune complex deposition in bullous pemphigoid or lupus. In plasma cells, PAS detects Russell bodies forming Mott cells.

- Differentiation Techniques PAS with Diastase (PAS-D)– It distinguishes glycogen from other PAS-positive structures. Glycogen disappears after diastase digestion and the area becomes colourless in the treated slide while appearing magenta in untreated slide.- Elements that remain magenta after digestion are enzyme-resistant (example: Alpha-1 Antitrypsin globules).

- Alcian Blue-PAS (AB-PAS)

– Acidic mucins become blue due to Alcian Blue.

– Neutral mucins remain magenta from PAS.

– Mixed mucins show purple or dark blue appearance. - Modified Protocols and Troubleshooting

- Modified PAS using Weigert iron hematoxylin and light green can be used for bone-cartilage interface where cartilage stains purple and bone stains blue-green.

- Fixation with glutaraldehyde may give false positive background because of free aldehyde groups. A blocking step is required if such fixative is used.

- Schiff reagent must be checked before staining. If it becomes pink in bottle, it is deteriorated and produces non-specific staining and therefore must be discarded.

Applications of Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

- It is used to demonstrate glycogen in different tissues like liver, skeletal muscles and cardiac muscles, and it helps in diagnosing glycogen storage diseases where glycogen accumulation is excess.

- It is applied with diastase digestion (PAS-D) to differentiate glycogen from other PAS-positive substances, and the diastase-resistant PAS staining is important to detect α-1 antitrypsin deficiency because the globules remain stained after digestion.

- It is the routine stain in renal biopsy for observing glomerular basement membrane, tubular basement membrane and other glycoprotein structures, and it is used to study thickening of basement membrane in diabetic nephropathy and different structural changes in glomerulonephritis.

- It is used to detect fungal organisms because fungal cell wall contains polysaccharides reacting strongly with PAS and organisms like Candida, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus and others appear magenta in tissues.

- It is helpful to diagnose Whipple disease as the macrophages contain PAS-positive diastase-resistant inclusions.

- It is used in tumour diagnosis for identifying glycogen-rich tumours like rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, renal cell carcinoma and other clear cell tumours, and it helps in detecting neutral mucins in adenocarcinomas.

- It is applied in dermatology for observing basement membrane zone changes in autoimmune diseases such as bullous pemphigoid and lupus erythematosus where thickening is seen.

- It is used to detect dermatophytes and fungal elements in skin and nails in cases of onychomycosis.

- It is used in hematology to detect cells like Mott cells and in erythroleukemia where erythroid precursors show strong PAS positivity.

- It is combined with Alcian Blue (AB-PAS) for differentiating neutral mucins from acidic mucins, and this is helpful in studying mucosubstances of gastrointestinal tract.

Advantages of Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

- It is a versatile staining method because it detects a wide range of carbohydrate substances like glycogen, neutral mucins, glycoproteins and polysaccharides, and it is used in many tissues for different diagnostic purposes.

- It is important in renal biopsy interpretation as it highlights glomerular basement membrane and tubular basement membrane clearly, and it helps in observing changes like thickening in diabetic nephropathy or segmental sclerosis in different kidney diseases.

- It is essential in liver pathology because with diastase digestion (PAS-D) it distinguishes true glycogen from other PAS-positive materials, and the diastase-resistant staining is useful for diagnosing α-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- It has the advantage of detecting neutral mucins which are not stained by acidic mucin stains, and when it is combined with Alcian Blue (AB-PAS) it helps in differentiating neutral mucins from acidic mucins.

- It is cost-effective and easy to perform, and it is an accessible method in laboratories that do not have fluorescence facilities, and it still shows high sensitivity in autoimmune skin diseases where PAS staining pattern correlates strongly with direct immunofluorescence.

- It is reliable in difficult tissue samples because modified PAS method can differentiate cartilage and bone when other stains fail due to loss of proteoglycans during processing, and it provides consistent staining for histological evaluation.

- It gives rapid identification of fungal organisms and tissue invasion, and it is useful when culture methods are slow or unsuccessful.

Limitations of Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

- It cannot distinguish glycogen from other PAS-positive substances, and a separate diastase-treated section (PAS-D) is required to confirm true glycogen digestion.

- It stains only neutral mucins while acidic mucins remain unstained, and this makes combination with Alcian Blue necessary when both types of mucins need to be differentiated.

- It produces poor contrast in some tissues because cartilage and bone can appear similar in colour, and a modified method is needed to separate these structures clearly.

- It can stain lipofuscin pigment which may be confused with other PAS-positive materials if additional stains are not used.

- It cannot identify fungal species because it shows only the carbohydrate wall of the fungus, and the identification must be done with other diagnostic methods.

- It is less sensitive than silver stains like GMS for detecting fungi, and scanty fungal elements or necrotic hyphae sometimes appear faint or even negative.

- It does not stain immune complex deposits directly in renal diseases, and it only shows the basement membrane changes around them.

- It has sensitivity limitations because histology with PAS may detect only around 80% of fungal infections compared to culture or molecular tests.

- It may show false-positive background staining when glutaraldehyde is used as fixative because remaining aldehyde groups react with Schiff reagent unless a blocking step is applied.

- It depends heavily on the quality of Schiff reagent which deteriorates quickly and becomes pink, and this leads to weak or non-specific staining.

- It requires precise oxidation timing with periodic acid because short oxidation or over-oxidation produces inconsistent staining.

- It requires proper washing after Schiff reagent because inadequate washing prevents proper development of magenta colour.

- It is affected by section thickness, and very thin sections are needed in renal pathology which makes the technique technically difficult.

- It uses colourless reagents that make it difficult to visually confirm correct application during the staining process, increasing the chance of handling errors.

- Aliabadi, P. M., Al-Qaisi, K., Reddy, V., Radbruch, A., Kobayashi, M., & Kubagawa, H. (2024). Periodic acid Schiff staining to detect Mott cells, aberrant plasma cells containing immunoglobulin inclusions called Russell bodies. Current Protocols, 4(9), e70005. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpz1.70005

- Anderson, J., & Rolls, G. (n.d.). An introduction to routine and special staining. Leica Biosystems.

- Bell, P. (2020, August 30). Liver biopsy interpretation: Special stains. AASLD. https://www.aasld.org/liver-fellow-network/core-series/pathology-pearls/liver-biopsy-interpretation-special-stains

- Celnovte. (2024, November 12). Exploring PAS staining: Key applications in pathological diagnosis. https://www.celnovte.com/solution/exploring-pas-staining-key-applications-in-pathological-diagnosis/

- Celnovte. (2024, September 5). Innovations in histology: Alcian Blue and PAS stain kit techniques. https://www.celnovte.com/solution/innovations-in-histology-alcian-blue-and-pas-stain-kit-techniques/

- Doan, C. (n.d.). Special stains – Which one, why and how? Part I: Mucins and glycogen. Leica Biosystems.

- Ellis, R. (2024, January 26). PAS diastase staining protocol. IHC WORLD. https://ihcworld.com/2024/01/26/pas-diastase-staining-protocol/

- Fu, D. A., & Campbell-Thompson, M. (2017). Periodic acid-Schiff staining with diastase. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1639, 145-149. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7163-3_14

- Guarner, J., & Brandt, M. E. (2011). Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 24(2), 247–280. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00053-10

- Harkin, D. (n.d.). Microscope tutorial – troubleshooting PAS stains [Video]. YouTube.

- IHC WORLD. (2024, January 26). PAS (Periodic Acid Schiff) staining protocol. https://ihcworld.com/2024/01/26/pas-periodic-acid-schiff-staining-protocol/

- Kazi, A. M., & Hashmi, M. F. (2023, June 26). Glomerulonephritis. StatPearls [Internet]. NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560644/

- Kjosness, K. M., Reno, P. L., & Serrat, M. A. (2023). Modified periodic acid‐Schiff (PAS) is an alternative to safranin O for discriminating bone–cartilage interfaces. JBMR Plus, 7(6), e10742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10742

- Life Worldwide. (2025). Histopathology of fungi. https://en.fungaleducation.org/histopathology/

- Myers, R. (n.d.). Special stain techniques for the evaluation of mucins. Leica Biosystems.

- Parry, N. (2025, May 29). Why pick PAS for histology? Bitesize Bio. https://bitesizebio.com/13413/why-pick-pas-for-histology/

- Rolls, G. (n.d.). Fixation and fixatives (2) – Factors influencing chemical fixation, formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde. Leica Biosystems.

- StainsFile. (n.d.). Periodic acid Schiff diastase. https://www.stainsfile.com/protocols/periodic-acid-schiff-diastase/

- StainsFile. (n.d.). Periodic acid Schiff reaction. https://www.stainsfile.com/theory/methods/schiffs-reagent-reactions/periodic-acid-schiff-reaction/

- Ventana Medical Systems, Inc. (2024). PAS staining kit [Instructions for use]. Roche Diagnostics.

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Periodic acid–Schiff stain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Periodic_acid%E2%80%93Schiff_stain

- Wulff, S. (Ed.). (2004). Guide to special stains. DakoCytomation.