Negative staining of viruses is the process in which the viral particles is visualized by embedding them in an electron-dense stain rather than staining the virus itself. It is the method where the background gets heavily stained while the virus remains unstained, so the particles appear as light structures against a dark surrounding.

It is the stain that forms a thin cast around the virion surface, outlining its shape and highlighting surface projections like capsomers or spikes. Uranyl acetate and phosphotungstic acid (PTA) are commonly used stains, and these salts form the dense matrix that helps in producing the contrasted image. It is a rapid technique because the viral suspension is allowed to adsorb on a carbon-coated grid and then the stain is applied in a small volume.

After blotting the excess liquid, a thin dried layer is formed which is observed directly under the electron microscope. It is used in diagnostic virology for quick morphological identification of unknown viruses as it gives an open view of the structural features. It is also the method used in laboratories to check quality and uniformity of viral preparations before cryo-EM analysis.

However, the resolution is limited to around 15–20 Å, and drying of the specimen can cause flattening or distortion of the virus. It is the technique where only a two-dimensional projection is obtained, so overlapping of upper and lower surface features may occur.

Principle of Negative Staining of Viruses

The principle of negative staining of viruses is based on the fact that the viral particles scatter electrons very weakly, so they appear transparent under the transmission electron microscope. It is the heavy metal stain that provides the contrast because these salts have high atomic numbers and scatter electrons strongly. In this method the stain does not bind to the virus, instead it fills the spaces around the particle and dries to form an electron-dense background. The virus excludes the stain due to its own structure, and this exclusion creates the clear outline of the particle. When the electron beam passes through the specimen the stained background absorbs and scatters most of the electrons, appearing dark, while the virus permits more electrons to pass and appears as a lighter silhouette. It is this difference in scattering that forms the negative image. During drying the stain also enters small gaps on the viral surface, so surface projections like spikes or capsomers are clearly marked. The process often flattens the virus against the grid because of dehydration, and since the technique produces only a two-dimensional projection some surface features may overlap in the final image.

Requirements for Negative Staining of Viruses

- Specimen Quality and Concentration

- It is required that a high viral titer is used because the method is less sensitive. A titer around 10⁵ to 10⁶ particles/mL is needed for locating particles within short search time.

- Purified preparations are kept around 0.01–1 mg/mL to obtain proper particle distribution.

- The sample must be clean and free of debris since large contaminants interfere with staining. Low-speed centrifugation (2000 × g for 3–5 minutes) is used for removing these.

- The buffer must be clean because salts, sucrose, glycerol or detergents cause uneven staining or crystallization.

- Electron Microscopy Grids and Surface Treatment

- Copper grids (200–400 mesh) with Formvar, Collodion, Pioloform or carbon film are generally used.

- It is important that the support film is hydrophilic. Glow discharge treatment is the common process used for making the surface hydrophilic.

- Some grids may be treated with poly-L-lysine or Alcian blue to improve spreading and adhesion.

- Staining Reagents and Preparation

- The stain must contain heavy metal salts for electron scattering.

- Uranyl acetate (0.5–2%) gives strong contrast but its acidic pH (4.2–4.5) may damage acid-sensitive viruses.

- Phosphotungstic acid (1–3%) can be buffered near neutral pH (7.0) and is used for viruses that are unstable in acid.

- Ammonium molybdate (1–2%, pH 7.0) is useful for osmotically sensitive envelopes though the contrast is lower.

- The staining solution is filtered through 0.22 μm filter immediately before use to remove crystals and microbial contaminants.

- Chemical Compatibility and Buffers

- Phosphate buffers must be avoided when uranyl acetate is used because uranyl ions form precipitates with phosphates.

- Distilled water or volatile buffers like ammonium acetate are used since they leave no salt residues after drying.

- If the sample is in incompatible buffer, washing drops of distilled water are applied to the grid after adsorption to exchange the buffer.

- Equipment and Procedural Controls

- Filter paper of good quality (e.g. Whatman #1) is required for blotting since the pressure and angle determine stain thickness.

- Self-closing tweezers are needed so that the grid is held securely without damaging the mesh during staining steps.

- Unfixed viral samples are handled in Class II Biosafety Cabinet. Grids may be inactivated using fixatives or UV exposure before microscopy.

- Artifact Mitigation

- It is known that air-drying leads to flattening or collapse of fragile viruses, and mild fixation (glutaraldehyde) helps in maintaining the structure.

- The depth of stain must be controlled carefully. Too thick stain hides the particle while too thin stain produces low contrast. Blotting time and stain concentration control this layer.

Preparation of Viral samples for Staining and Visualization

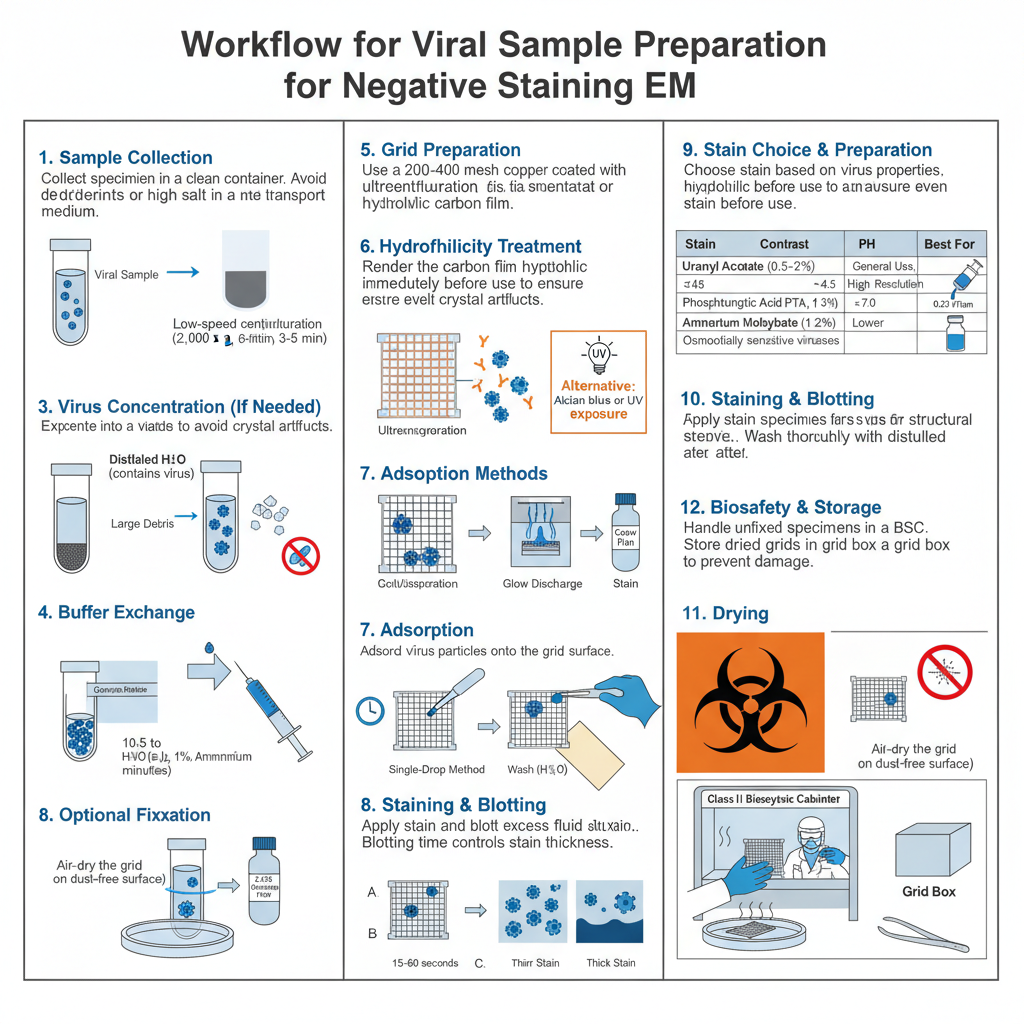

- Sample collection

- It is required that specimens are collected into clean containers.

- Avoid detergents or high salt in the transport medium.

- Initial clarification

- The sample is cleared of large debris by low-speed centrifugation (e.g. 2,000 × g for 3–5 minutes).

- The supernatant is used for further processing.

- Concentration of virus

- If titer is low, the virus is concentrated by ultracentrifugation (pelleting) or by using an Airfuge.

- Immunoaggregation may be used to clump and concentrate particles when appropriate.

- Buffer exchange and cleaning

- The suspension is exchanged into distilled water or a volatile buffer (e.g. 1% ammonium acetate) to avoid salt residues.

- Washing on the grid by touching to drops of distilled water is performed if sample contains incompatible components.

- Removal of interfering substances

- High concentrations of sucrose, glycerol or detergents is removed because they give poor spreading or artifacts.

- If necessary, perform dialysis or brief wash steps to reduce these components.

- Optional fixation

- Fragile specimens is fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for structural preservation when required.

- After fixation the sample is washed thoroughly with distilled water to remove fixative before staining.

- Grid selection and film preparation

- Copper grids (200–400 mesh) coated with Formvar, Collodion, Pioloform or carbon film is used.

- Freshly evaporated carbon films is preferred because they are hydrophilic.

- Hydrophilicity treatment

- Grids is glow-discharged in a plasma cleaner immediately before use to render the surface hydrophilic.

- If glow discharge is unavailable, grids is treated with 1% Alcian blue or exposed to UV to restore hydrophilicity.

- Adsorption — single-drop method

- A drop of viral suspension (3–5 µL) is placed on the grid and allowed to adsorb for 10 seconds to several minutes depending on particle affinity.

- Excess fluid is blotted at the grid edge with filter paper.

- Adsorption — sequential (washing) method

- The sample is applied and allowed to adhere.

- The grid is touched to drops of distilled water or volatile buffer to wash away salts.

- The grid is then exposed to the negative stain.

- Stain choice and preparation

- Uranyl acetate (0.5–2%) is used for high contrast but its pH (4.2–4.5) may harm acid-sensitive viruses.

- Phosphotungstic acid (1–3%, pH 7.0) is used when neutral pH is required.

- Ammonium molybdate (1–2%, pH 7.0) is chosen for osmotically sensitive envelopes though contrast is lower.

- All stains is filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter immediately before use to remove crystals.

- Staining exposure

- Apply stain drop or touch grid to stain drop for 15–60 seconds as appropriate for stain and specimen.

- Side-blot the grid to control stain thickness. The blotting time determines whether particle is enveloped by stain or buried by stain.

- Blotting and drying

- Excess stain is removed by touching the grid edge with high-quality filter paper (e.g. Whatman #1).

- The grid is air-dried on a dust-free surface.

- Inactivation and biosafety handling

- Work with unfixed specimens is performed in a Class II Biosafety Cabinet.

- Grids may be inactivated by chemical fixation or brief UV exposure before removal from containment.

- Storage and transfer to microscope

- Dried grids is stored in grid boxes and handled with self-closing tweezers to avoid damage.

- Transfer to the electron microscope is performed after appropriate inactivation and documentation.

Procedure for Negative Staining of Viruses

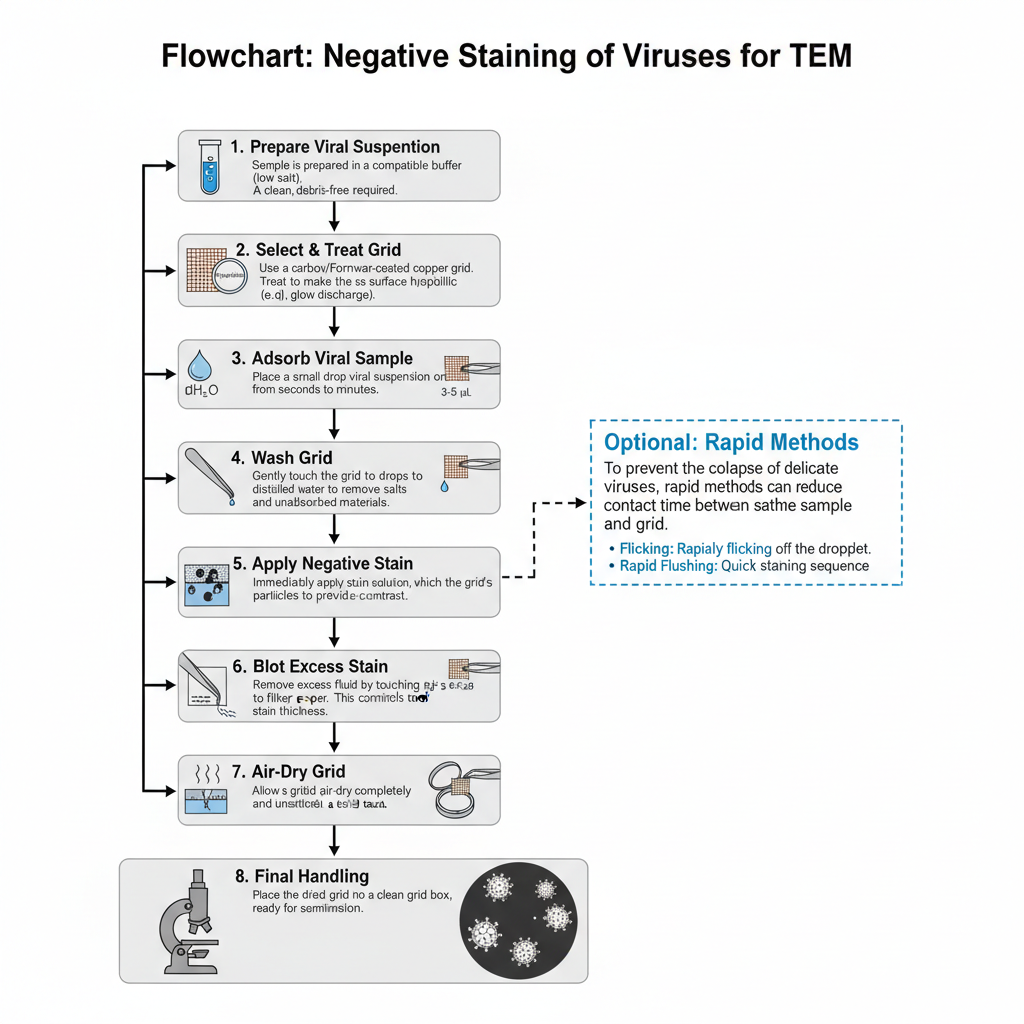

- Preparation of viral suspension

- The sample is prepared in a compatible buffer since high phosphate or salt causes precipitation when uranyl stains is used.

- A clean suspension is required so that debris does not interfere with the staining.

- Selection and treatment of grid

- Copper mesh grids coated with carbon or Formvar film is used for supporting the specimen.

- The grid must be hydrophilic. This is achieved by glow discharge or by treating with Alcian blue solution.

- Hydrophilic surface helps the sample to spread evenly instead of forming beads.

- Adsorption of viral sample

- A small drop (3–5 µL) of viral suspension is placed on the coated side of the grid.

- The adsorption time ranges from few seconds to several minutes depending on concentration of particles.

- The grid is held with self-closing tweezers to avoid damage.

- Washing step (in two-droplet method)

- The grid is touched gently to drops of distilled water or volatile buffer to remove salts and unadsorbed materials.

- This step reduces crystallization and uneven stain deposition.

- Exposure to negative stain

- The stain solution such as uranyl acetate or phosphotungstic acid is applied immediately after washing.

- The stain envelops the particle and forms the surrounding matrix required for contrast under the TEM.

- Blotting of excess stain

- Excess fluid is removed by touching the edge of the grid to filter paper.

- Side blotting controls the stain thickness. Too thick stain hides the structural details while too thin stain gives poor contrast.

- Drying of the grid

- The grid is air-dried completely so that the stain forms a firm cast around the viral particle.

- Drying must be undisturbed to avoid formation of artifacts.

- Optional rapid methods

- Flicking or rapid flushing may be used to reduce the time of contact between sample and grid.

- These methods help to prevent collapse or flattening of delicate viruses.

- Final handling before TEM

- The dried grid is placed in a clean grid box.

- It is then ready for examination under the transmission electron microscope.

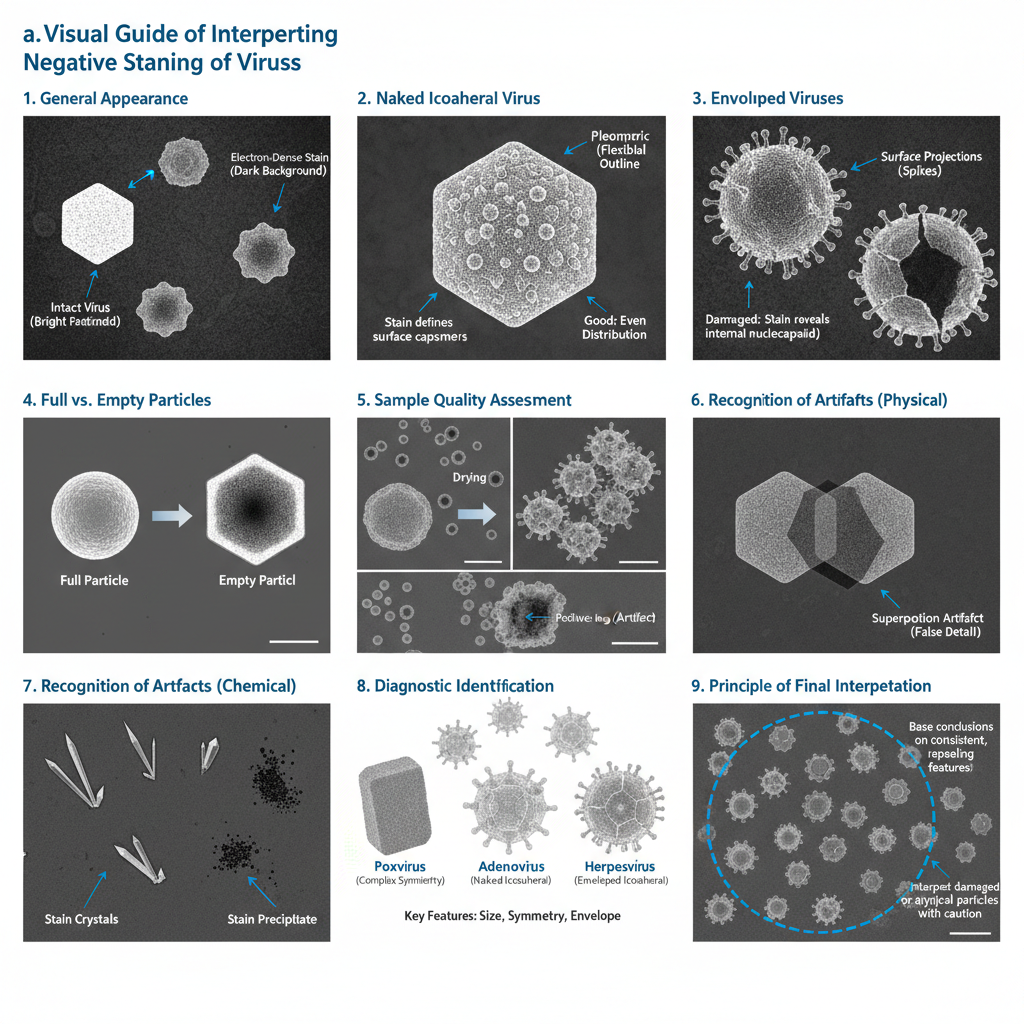

Results and Interpretation of Negative Staining of Viruses

- General appearance of stained particles

- In a proper preparation the viruses appear as light or bright particles because the stain surrounds them but does not enter intact structures.

- The background becomes dark due to the heavy metal matrix which forms the contrasting field.

- Resolution and contrast obtained

- The contrast is high since the stain produces strong electron density.

- The image usually gives around 15–20 Å clarity which is sufficient for observing external morphology though not atomic details.

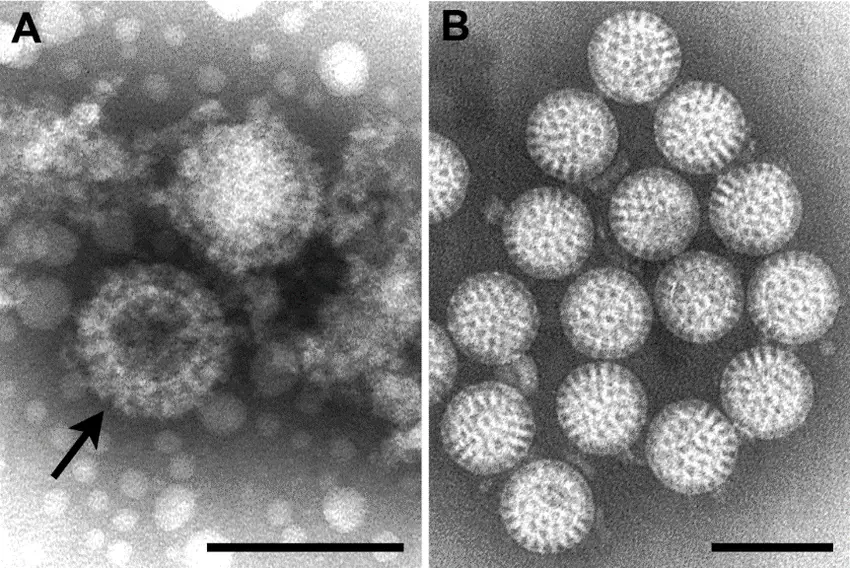

- Appearance of naked icosahedral viruses

- These viruses appear as rigid spherical or hexagonal outlines.

- The stain may settle between capsomers producing bead-like surface patterns.

- Small icosahedral particles appear smooth or slightly textured.

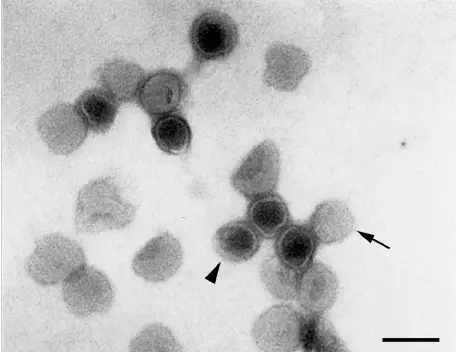

- Appearance of enveloped viruses

- Enveloped particles show pleomorphism because the lipid membrane is deformable.

- Surface projections such as spikes appear as projections at the periphery.

- If the envelope is damaged, the stain may enter and reveal the nucleocapsid.

- Interpretation for diagnostic purpose

- Viruses is generally recognized by size, symmetry and presence of envelope.

- Distinct morphologies help identify families such as brick-shaped poxviruses or icosahedral herpesviruses.

- These observations support rapid identification when the agent is unknown.

- Internal structural interpretation

- When stain penetrates inside, the center becomes dark indicating empty or damaged particles.

- The lighter rim indicates remaining capsid structure and is used to estimate the ratio of full to empty particles.

- Assessment of sample quality

- A good field shows even distribution of particles without clumping.

- Aggregation indicates heterogeneity or chemical incompatibility with stain.

- Positive staining of the virus instead of the surrounding stain shows pH or buffer mismatch.

- Recognition of flattening artifacts

- Drying causes collapse of spherical or cylindrical particles resulting in disk-like appearances.

- This is interpreted as an artifact since the real particle height is lost during drying.

- Recognition of superposition effects

- Because TEM gives a two-dimensional projection, the top and bottom features overlap.

- This overlap sometimes creates patterns that may be mistaken for real structural details.

- Identification of stain artifacts

- Crystallization of stain appears as dark or needle-like deposits.

- These arise due to phosphate or incompatible buffer and must not be confused with viral components.

- Final interpretation

- Only those features consistently seen across multiple particles is taken as actual morphology.

- Particles showing extreme distortion or heavy internal staining are interpreted with caution since they indicate damage.

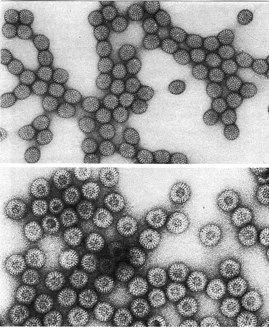

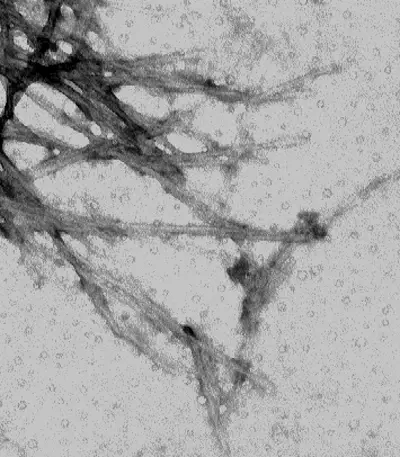

Pictures of Negative staining of Viruses

Advantages of Negative Staining of Viruses

- It is a simple method and the whole staining process can be completed very quickly. The preparation needs only basic electron microscopy facilities and can be done at room temperature without special vitrification equipment.

- The method does not need specific reagents like primers or antibodies, so it can detect unknown viruses only by observing their morphology. It can also show mixed infections since all particles present in the sample are visible together.

- It gives a very high contrast image because the heavy metal stain scatters electrons strongly. Small particles and fine surface features become clearly outlined as the stain forms a mold around the viral surface.

- It is used as an initial screening step to check the quality of viral preparations. The technique helps to observe purity, concentration, aggregation, or damaged particles before performing more advanced microscopy.

- The negatively stained grids show better stability under the electron beam and are less prone to radiation damage. Stains like uranyl acetate also have a fixing effect, allowing the grids to be stored for later examination.

Limitations of Negative Staining of Viruses

- The method has limited resolution and the stain grains restrict the visibility of fine structural details. Only the general outline of the virus is seen and internal structures are not clearly resolved unless the stain enters the particle.

- The drying process causes flattening of the virus because of surface tension, and the particles may collapse or become distorted on the grid. Fragile assemblies can also break during adsorption and drying.

- Some viruses show preferred orientation on the support film which limits the viewing angles and affects interpretation of structural features.

- The stains may react with the buffer components resulting in precipitates, and acidic stains like uranyl acetate can damage acid-sensitive viruses. Phosphotungstic acid may disturb membrane structures and form artificial figures.

- Sometimes the stain binds to the viral surface leading to positive staining or aggregation which makes the image difficult to interpret.

- The final image is a two-dimensional projection, and the features from upper and lower surfaces of the particle get superimposed. This may blur the details or create visual artifacts.

- The technique has low sensitivity and requires a higher concentration of viral particles for detection, so samples with low viral load may not be visualized.

Applications of Negative Staining

- It is used in diagnostic virology to detect viruses directly from clinical specimens. The method helps in identifying unknown pathogens based on their morphology without the need for specific reagents.

- It is applied for examining stool, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, and blister fluid to detect viruses that cannot be grown easily in culture, such as rotavirus, norovirus, and polyomavirus.

- It is important in outbreak investigations because rapid staining allows quick recognition of emerging or bioterrorism-related viruses. This has been used historically in early identification of Ebola virus, SARS coronavirus, and other newly detected agents.

- It helps in distinguishing morphologically similar viruses. The method can separate smallpox from chickenpox or monkeypox by observing the unique features of their capsids.

- It is used in structural biology as a preliminary step before cryo-electron microscopy. The staining allows checking of particle integrity, concentration, and uniformity so that the sample is optimized for high-resolution work.

- It is helpful in adjusting purification or buffer conditions since the viral particles can be visualized for aggregation or damage at each step.

- It can be combined with immuno-electron microscopy where antibodies cause aggregation of similar particles, increasing the chance of detection and providing information on viral protein locations.

- It is used with electron tomography to form three-dimensional views of stained particles, giving additional surface or internal features that are not clear in simple two-dimensional images.

- Creative Biostructure. (n.d.). Negative staining vs cryo-EM. Retrieved from https://www.creative-biostructure.com/resource-negative-staining-cryo-em-techniques.htm

- Goldsmith, C. S., & Miller, S. E. (2009). Modern uses of electron microscopy for detection of viruses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 22(4), 552–563. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00027-09

- Indiana University Bloomington Electron Microscopy Center. (n.d.). Negative staining procedures. Retrieved from http://iubemcenter.indiana.edu/equipment/tips-and-help/negative-staining-procedures.html

- Mast, J., & Demeestere, L. (2009). Electron tomography of negatively stained complex viruses: Application in their diagnosis. Diagnostic Pathology, 4(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-4-5

- Sanchez, J., & Ke, Z. (2021). Negative stain grid preparation [PDF]. University of Wisconsin-Madison Cryo-EM Research Center. https://cryoem.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/341/2021/01/Negative_Stain_Grid_Preparation_21Jan2021.pdf

- Scarff, C. A., Fuller, M. J. G., Thompson, R. F., & Iadaza, M. G. (2018). Variations on negative stain electron microscopy methods: Tools for tackling challenging systems. Journal of Visualized Experiments, (132), e57199. https://doi.org/10.3791/57199

- University of Cape Town Division of Medical Virology. (n.d.). Negative staining. Retrieved from https://health.uct.ac.za/medical-virology/teaching/negative-staining

- University of Oxford. (n.d.). Negative staining techniques [PDF]. Retrieved from http://web.path.ox.ac.uk/~bioimaging/bitm/instructions_and_information/em/neg_stain.pdf

- University of Rochester Medical Center. (n.d.). Visualization of viral particles by negative staining electron microscopy. Retrieved from https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/research/electron-microscope/services/protocols-techniques/negative-staining-electron-microscopy.aspx