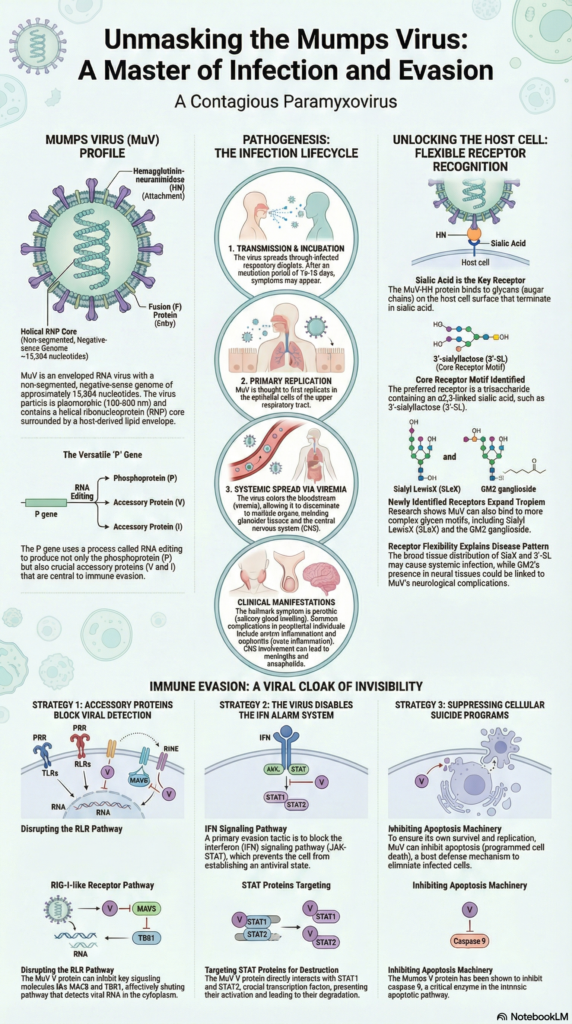

Mumps virus (MuV) is the causative agent of the acute infectious disease known as mumps. It is scientifically classified as Orthorubulavirus parotitidis and belongs to the family Paramyxoviridae. It is an enveloped virus having single-stranded negative sense RNA genome and the viral particle is pleomorphic in nature with size ranging from about 100–600 nm. Humans are the only natural host of this virus and the infection is transmitted mainly by direct contact with saliva and respiratory droplets from infected person.

After entry into the body the virus is first multiplied in upper respiratory tract and later spreads to different tissues. It mainly affects the salivary glands especially the parotid glands which leads to characteristic painful swelling. In some cases the virus also spreads to central nervous system and other glandular tissues. The viral envelope contains surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) and fusion protein (F) which are helping in attachment and entry of virus into host cells. Although many genotypes of mumps virus are present throughout the world they belong to single serotype and therefore vaccination provides effective protection against the disease.

History of Mumps Virus

The history of mumps virus is very old and it has been known to human beings since ancient time. The earliest description of the disease was given by Hippocrates in the 5th century BCE. He described the swelling of salivary glands and testicular inflammation which are now recognised as parotitis and orchitis. At that time the cause of the disease was not known and it was only identified on the basis of clinical symptoms. The term mumps was introduced much later during the late 16th century and it was derived from the Old English word “mump” which refers to grimacing or difficulty in speaking due to swelling of jaw.

For many centuries mumps remained an important infectious disease affecting children and adults. It was also a serious problem during military conditions. During World War I mumps was one of the major causes of hospitalization among soldiers and it ranked just below influenza and gonorrhea. This shows that the disease was widespread and highly contagious before the development of effective preventive measures.

The viral nature of mumps was established in the year 1934. Claud Johnson and Ernest Goodpasture demonstrated that the disease is caused by a filterable agent present in saliva and they successfully transmitted the infection from human to rhesus monkeys. Later in 1945 the virus was isolated and grown in embryonated eggs which helped in further research and vaccine development. Early inactivated vaccines were developed but these produced only short-term immunity and therefore they were discontinued.

A major breakthrough occurred in 1967 when a live attenuated vaccine was developed by Maurice Hilleman. The virus was isolated from his daughter Jeryl Lynn and this strain became widely used. In 1971 the mumps vaccine was combined with measles and rubella vaccine to form the Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine. After the introduction of this vaccine the incidence of mumps was reduced drastically in many countries.

In recent years the history of mumps virus has entered a new phase. Since 2006 several outbreaks have been reported even in highly vaccinated populations especially in close-contact settings like colleges and universities. Along with epidemiological changes the virus has also undergone taxonomic reclassification. It was earlier placed under genus Paramyxovirus then Rubulavirus and now it is classified as Orthorubulavirus parotitidis. This historical progression shows how understanding of mumps virus has evolved with scientific advancement.

Taxonomy and Classification of Mumps Virus

Scientific Classification

- Realm – Riboviria.

- Kingdom – Orthornavirae.

- Phylum – Negarnaviricota.

- Class – Monjiviricetes.

- Order – Mononegavirales.

- Family – Paramyxoviridae.

- Subfamily – Rubulavirinae (earlier placed under Paramyxovirinae).

- Genus – Orthorubulavirus (formerly Rubulavirus).

- Species – Orthorubulavirus parotitidis.

Nomenclature History

- The virus was initially placed under genus Paramyxovirus in 1971.

- It was later established as the type species of genus Rubulavirus in 1995.

- In 2018 Rubulavirus genus was removed and replaced by Orthorubulavirus.

- In 2023 species name was changed from Mumps orthorubulavirus to Orthorubulavirus parotitidis.

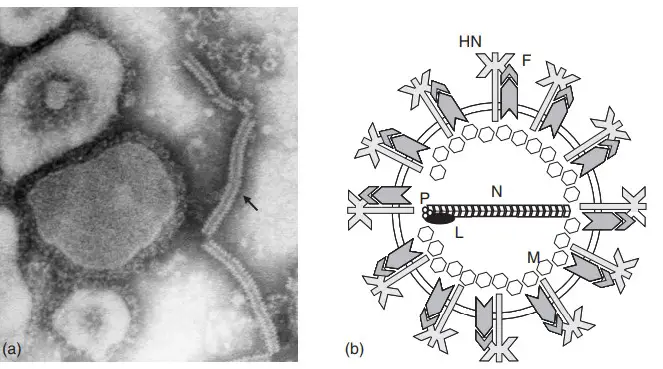

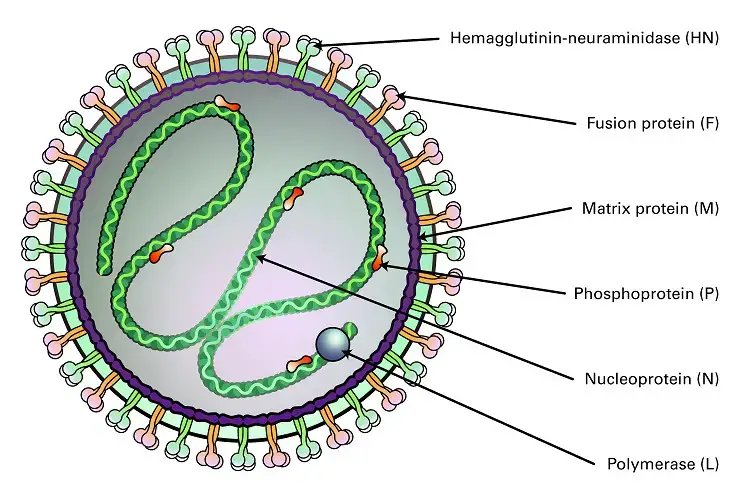

Structure of Mumps Virus

The structure of mumps virus can be described under following points–

General Characteristics

- It is a member of family Paramyxoviridae and subfamily Rubulavirinae.

- The virus is pleomorphic in nature and does not show a fixed shape.

- The viral particle is generally spherical but irregular forms are also seen.

- The size of virus particle ranges from about 100 nm to 600 nm in diameter.

Viral Genome

- The genome is single stranded negative sense RNA.

- It is non segmented and present as a single continuous strand.

- The length of RNA genome is about 15,384 nucleotides.

- It follows the rule of six which means total number of nucleotides is multiple of six for proper replication.

Envelope

- The virus is surrounded by an outer envelope.

- The envelope is composed of lipid bilayer derived from host cell membrane.

- Glycoprotein spikes are present on the envelope surface.

- These spikes extend about 12–15 nm from the viral surface.

Structural Proteins

- Nucleoprotein (N)– It surrounds the RNA genome and forms helical nucleocapsid protecting RNA from degradation.

- Phosphoprotein (P)– It acts as a cofactor and helps in binding RNA polymerase to nucleocapsid.

- Large protein (L)– It is RNA dependent RNA polymerase and is responsible for viral replication.

- Matrix protein (M)– It is present below the envelope and connects nucleocapsid with envelope proteins.

- Fusion protein (F)– It helps in fusion of viral envelope with host cell membrane during entry.

- Hemagglutinin neuraminidase (HN)– It is involved in attachment of virus to host cell receptors and prevents viral aggregation.

- Small hydrophobic protein (SH)– It helps in inhibiting apoptosis of host cell which supports viral survival.

Internal Core (Ribonucleoprotein Complex)

- It consists of RNA genome associated with nucleoprotein and polymerase complex.

- The structure is helical and hollow in nature.

- The diameter of the nucleocapsid is about 17–20 nm.

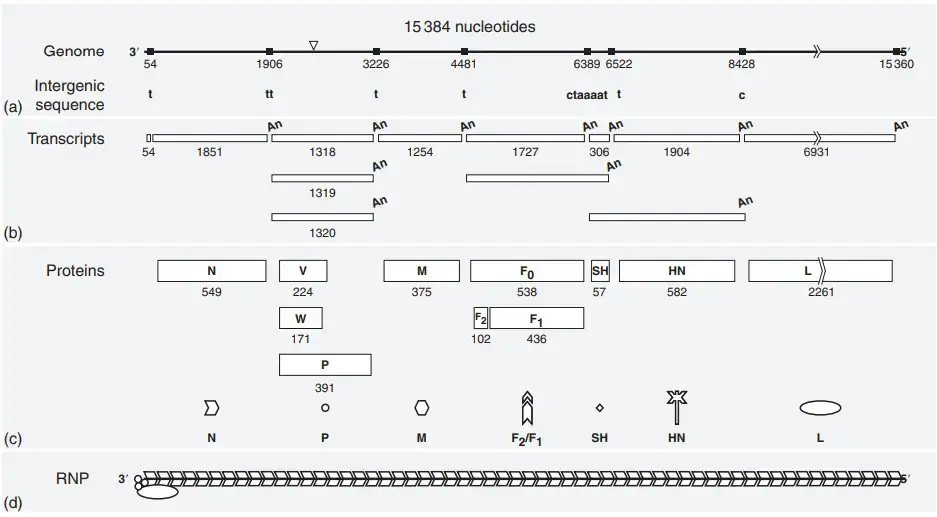

Genome and Genome Structure of Mumps Virus

- It is a single stranded non-segmented negative sense RNA genome.

- The genome length is about 15,384 nucleotides.

- It strictly follows the Rule of Six where total nucleotides is multiple of six for proper replication.

- The genomic RNA is rich in guanine and cytosine and G+C content is around 42.3%.

- The RNA genome is enclosed by nucleoprotein (N) forming ribonucleoprotein complex.

- This RNP is flexible helical and appears like a hollow tube.

- It is the structure that protects RNA from host nucleases and act as template for transcription and replication.

- The RNA dependent RNA polymerase complex is attached to RNP.

- This polymerase complex is made of Large (L) protein and Phosphoprotein (P).

- The genome contains seven tandemly linked transcription units.

- The gene arrangement is from 3′ end to 5′ end as follows–

- N gene coding nucleoprotein.

- P/V/I gene coding phosphoprotein V protein and I protein.

- M gene coding matrix protein.

- F gene coding fusion protein.

- SH gene coding small hydrophobic protein.

- HN gene coding hemagglutinin neuraminidase protein.

- L gene coding large RNA polymerase protein.

- The genome is flanked by regulatory extracistronic regions.

- A leader sequence of about 55 nucleotides is present at 3′ end.

- A trailer sequence of about 24 nucleotides is present at 5′ end.

- Intergenic sequences of variable length separate each gene.

- The P gene undergoes co-transcriptional RNA editing.

- The unedited mRNA produces V protein.

- Insertion of two guanine residues produces P protein.

- Insertion of one or four guanine residues produces I protein.

- There is only one serotype of mumps virus.

- The genome shows genetic diversity forming about 12 genotypes (A–N excluding E and M).

- The differentiation of genotypes is mainly based on sequence variation in SH and HN genes.

Properties of the Proteins of Mumps Virus

The protein assignment of mumps virus is mainly based on similarity with other paramyxoviruses. Direct gene identification has not been performed. The similarities are very clear and hence the classification is accepted.

The mumps virus virion contains six structural proteins. These are N P M L HN and F proteins. Among these HN and F are membrane spanning glycosylated proteins.

Structural Proteins

- Nucleocapsid protein (N)

- It is a phosphorylated structural protein of RNP.

- It protects the viral genome from RNases.

- It may have a role in regulation of transcription and replication.

- It is also referred to as S antigen.

- Phosphoprotein (P)

- It is a phosphorylated protein associated with the RNP.

- It may help in solubilization of the N protein.

- It plays a role in viral RNA synthesis.

- Large protein (L)

- It is associated with the RNP complex.

- It has RNA dependent RNA polymerase activity.

- It is involved in capping methylation and polyadenylation of viral mRNA.

- Matrix protein (M)

- It is a hydrophobic protein present on the inner side of membrane.

- It is involved in virus budding.

- It interacts with N HN and F proteins during assembly.

- Fusion protein (F)

- It is an acylated and glycosylated protein.

- It is activated by proteolytic cleavage.

- It exists as F2–F1 heterodimer.

- It helps in fusion of virion membrane with plasma membrane.

- This process also involves HN protein.

- It acts as hemolysis antigen.

- Hemagglutinin–neuraminidase protein (HN)

- It is acylated and glycosylated in nature.

- It shows hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activity.

- It has an accessory role in membrane fusion.

- It is considered as major V antigen.

Additional and Nonstructural Proteins

- Small hydrophobic protein (SH)

- It is a membrane protein with unknown function.

- It is detected in infected cells.

- It has not been clearly detected in virions.

- In some strains it is expressed as readthrough transcript with F gene.

- The SH protein is not essential for viral growth in tissue culture.

- Nonstructural V protein

- It is a phosphorylated protein.

- It contains a cysteine rich domain.

- This domain may be involved in metal binding.

- It induces proteasomal degradation of STAT1.

- It targets STAT3 for ubiquitination.

- Earlier it was known as NS1.

- Nonstructural W protein

- It is also a phosphorylated protein.

- Its exact function is not clearly known.

- It may be produced due to RNA misediting.

- Earlier it was known as NS2.

Replication of Mumps Virus

The replication of mumps virus takes place completely in the cytoplasm of host cell. The nucleus does not take part in viral replication process.

1. Attachment

- Attachment is the first step of replication.

- The Hemagglutinin–neuraminidase (HN) protein is involved in attachment.

- It binds with sialic acid receptors present on host cell surface.

2. Entry

- Entry of virus occurs immediately after attachment.

- The Fusion (F) protein mediates fusion of viral envelope with host cell membrane.

- The viral nucleocapsid is released directly into the cytoplasm.

3. Transcription

- Transcription starts after uncoating of nucleocapsid.

- The viral RNA dependent RNA polymerase is composed of P and L proteins.

- It uses negative sense genomic RNA as template.

- Viral mRNAs are synthesized for protein formation.

4. RNA Editing

- RNA editing occurs during transcription of P gene.

- The polymerase inserts non templated guanine residues.

- This process results in formation of P V and I proteins.

5. Translation

- Translation of viral mRNA occurs on host ribosomes.

- Viral structural and nonstructural proteins are synthesized.

- The F and HN glycoproteins enter endoplasmic reticulum.

- These proteins are processed in Golgi complex.

- They are transported to the plasma membrane.

6. Genome Replication

- Genome replication begins after sufficient N protein accumulates.

- The polymerase shifts from transcription to replication.

- A positive sense antigenome RNA is first synthesized.

- This antigenome acts as template for new negative sense genomic RNA.

7. Assembly

- Assembly of virus particles occurs at plasma membrane.

- The Matrix (M) protein migrates to the cell surface.

- It links nucleocapsid with HN and F glycoproteins.

8. Budding

- Newly formed virus particles are released by budding.

- Budding occurs from the host cell membrane.

- The viral envelope is derived from host membrane.

9. Release

- Release of virus is facilitated by HN protein.

- The neuraminidase activity cleaves sialic acid residues.

- This prevents clumping of newly formed virions.

Pathogenesis of Mumps Virus

Transmission and Entry

- The virus enters the body through nose or mouth.

- Entry occurs by inhalation of infected respiratory droplets.

- Direct contact with saliva also helps in transmission.

- Contaminated fomites may act as source of infection.

- The Hemagglutinin–neuraminidase (HN) protein binds to sialic acid receptors.

- This binding initiates infection of host cells.

Primary Replication

- The initial site of infection is upper respiratory tract.

- The virus replicates in epithelial cells of nasopharynx.

- After local replication the virus spreads to regional lymph nodes.

Viremia

- The virus enters the bloodstream producing primary viremia.

- This allows dissemination to different parts of body.

- The viremic phase lasts for about 3 to 5 days.

- Infected T lymphocytes may transport virus to tissues.

- Replication in target organs releases more virus into blood.

- This results in secondary viremia.

Target Organ Infection

- The virus shows affinity for glandular tissues.

- Parotid salivary glands are most commonly affected.

- Testes ovaries pancreas and thyroid may also be involved.

- The virus is highly neurotropic.

- Central nervous system invasion is common.

- Meningitis or encephalitis may develop.

- The virus replicates in kidneys.

- It is excreted in urine causing viruria.

Mechanism of Tissue Damage

- In parotid glands viral replication causes necrosis of ductal cells.

- Inflammation leads to swelling and pain.

- In testes infection causes edema congestion and necrosis.

- Seminiferous tubules may be damaged.

- Testicular atrophy can occur in severe cases.

- The virus enters CNS through choroid plexus.

- Ependymal cells lining ventricles are infected.

Immune Evasion

- The viral V protein interferes with interferon response.

- This delays clearance of virus by immune system.

- The SH protein inhibits apoptosis of infected cells.

- This helps in survival of virus within host.

Shedding and Contagiousness

- The virus is shed mainly in saliva.

- Maximum infectivity occurs from 2 days before parotitis.

- Shedding continues up to 5 days after onset of parotitis.

- Many infected individuals remain asymptomatic.

- Asymptomatic persons can still transmit the virus.

Epidemiology of Mumps Virus

- Mumps is a viral disease that occurs worldwide.

- It is endemic in many regions.

- On an average about 500,000 cases are reported every year.

- Humans are the only natural reservoir of mumps virus.

- No animal or insect reservoir is present.

- The virus is transmitted mainly by direct contact.

- It spreads through saliva and respiratory droplets.

- Infection can also occur by contact with contaminated objects.

- Asymptomatic persons can transmit the virus.

- Individuals in prodromal stage can also spread infection.

- The infectious period starts before clinical symptoms appear.

- A person is infectious from about 2 days before parotitis.

- Infectivity continues up to 5 days after onset of parotitis.

- Viral shedding in saliva may occur from 7 days before swelling.

- Shedding may continue till 9 days after onset of swelling.

- Transmission is highest just before and after parotitis appears.

- Mumps is a highly contagious disease.

- The basic reproductive number (R₀) is high.

- It ranges between 10–12 or 4–7 in susceptible population.

- The disease shows seasonal variation.

- In temperate regions cases increase in late winter and early spring.

- In hot climates cases may occur throughout the year.

- Before vaccination epidemics occurred every 2 to 5 years.

- Mumps was mainly a childhood disease earlier.

- Highest incidence was seen in children of 5 to 9 years.

- In vaccinated populations infection is now common in adolescents.

- Young adults are also affected due to waning immunity.

- Outbreaks commonly occur in crowded settings.

- These include schools colleges and universities.

- Military barracks and correctional facilities are also affected.

- Close contact communities show higher risk of outbreaks.

- Vaccination has greatly reduced mumps incidence.

- More than 99% reduction in cases was observed in some countries.

- Resurgence of cases has been reported since 2006.

- This occurs even in highly vaccinated populations.

- Waning immunity after 10–15 years is an important factor.

- Antigenic mismatch between vaccine strain and circulating strains also contributes.

Clinical manifestations of Mumps Virus

- It is seen that many infections remain asymptomatic and these cases occur in around 20–30% of infected individuals.

- Some cases show only mild respiratory symptoms that appear similar to common cold infection.

- A short prodromal phase is present in many patients which shows low-grade fever, headache, myalgia, general tiredness (malaise), and loss of appetite.

- Parotitis is the major symptom and it is the painful swelling of the parotid salivary gland. It may appear unilateral or bilateral.

- Swelling of other salivary glands like submandibular and sublingual glands is also seen in some patients.

- There is pain at the angle of the jaw and pain increases during chewing or swallowing acidic liquids.

- The swelling can push the earlobe upward and outward and sometimes the jaw angle becomes hard to locate.

- Orchitis is one of the common complications in post-pubertal males and it is marked by sudden fever, testicular pain, swelling, nausea, and vomiting.

- Testicular atrophy may occur as a later effect but sterility is very rare.

- Oophoritis can occur in females and it causes lower abdominal or pelvic pain.

- Mastitis is also reported in some infected individuals.

- Aseptic meningitis is an important nervous system manifestation and shows headache, neck stiffness, and vomiting.

- Encephalitis occurs in fewer cases and it shows drowsiness, seizures, or even coma.

- Sudden sensorineural hearing loss can appear and usually affects one ear.

- Rare neurological findings include facial palsy, ataxia, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and hydrocephalus.

- Pancreatitis is seen in some cases and it causes severe epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting.

- Nephritis occurs but it is usually mild and may show viruria.

- Myocarditis is another complication which is mostly detected by ECG changes.

- Arthritis or arthralgia occurs and the pain may shift from one joint to another.

- Thyroiditis can also occur as inflammatory involvement of the thyroid gland.

Laboratory Diagnosis Methods of Mumps Virus

RT-PCR (Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction)

- It is the preferred test as it detects the viral RNA directly from patient samples.

- Buccal or oral swab is the main specimen and is collected within 3 days of parotitis, but detection is possible up to 8–9 days.

- Parotid gland is gently massaged before collecting the swab to increase the viral particles in the sample.

- Viral RNA is also detected from throat swab, urine (up to 14 days), and CSF.

- It is used for identifying virus strains for epidemiological studies.

- A negative test does not exclude infection.

Serological Tests (Antibody Detection)

- IgM detection indicates recent infection and is usually detectable in early days of the illness.

- IgM response may be low or absent in vaccinated individuals and may show false results in some cases.

- IgG test requires paired sera, taken during early infection and again after 2 weeks, and a rise in IgG titer is interpreted as recent infection.

- Pre-vaccinated individuals can already have high IgG titers and this makes interpretation difficult.

Viral Culture

- It is the method where the virus is isolated in cell culture systems like Vero cells or monkey kidney cells.

- Samples such as saliva, urine, blood, CSF, and tissue fluids are used for isolation.

- The virus is identified by cytopathic effects, hemadsorption or by immunofluorescence method.

- Isolation from saliva is most successful within first 4–5 days of symptoms.

Non-specific Laboratory Findings

- Serum amylase is increased in many cases because of salivary gland or pancreatic involvement.

- Blood count shows leukopenia with lymphocytosis or neutropenia in several patients.

- CSF in meningitis cases shows increased cells, slightly low or normal glucose and mildly raised protein.

Treatment of Mumps Virus

- It is mainly supportive treatment as no specific antiviral drug is available for mumps virus.

- The disease is self limiting and recovery occurs when immune system clears the virus.

- Supportive care is given to relieve symptoms such as fever and pain.

- Adequate rest is advised and bed rest is recommended during acute stage.

- Proper hydration is maintained and sufficient fluid intake is necessary.

- Intravenous fluids is given when vomiting occurs due to complications like pancreatitis.

- Soft and bland diet is advised to reduce pain during chewing.

- Acidic foods such as citrus juices and vinegar are avoided as it increases salivary secretion and pain.

- Analgesics and antipyretics such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen is used to control pain and fever.

- Aspirin is avoided in children due to risk of Reye syndrome.

- Warm or cold compresses are applied over swollen parotid glands for relief.

- Gargling with warm salt water may help in reducing discomfort.

- In orchitis bed rest is essential and scrotal support is provided using cotton or adhesive tape bridge.

- Ice packs are applied to relieve testicular pain and swelling.

- Corticosteroids are sometimes used but their role in faster recovery is not proven.

- In mumps meningitis lumbar puncture may be done to reduce headache.

- Anticonvulsant drugs are given if seizures occur.

- Patient is isolated for about 5 days after onset of parotitis to prevent spread of infection.

- Standard and droplet precautions are followed in hospital settings.

Prevention and control of Mumps Virus

- Vaccination is the main method for prevention of mumps virus infection.

- It is the most effective way to reduce morbidity and mortality of disease.

- Live attenuated mumps virus vaccine is used for immunization.

- The vaccine is given in combined form as Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) or Measles-Mumps-Rubella-Varicella (MMRV).

- Different vaccine strains are available such as Jeryl Lynn strain Urabe AM9 and Leningrad-Zagreb strain.

- Rubini strain is not recommended due to low effectiveness.

- In children two doses of vaccine is given.

- First dose is administered at 12–15 months of age.

- Second dose is given at 4–6 years of age.

- Adults born after 1957 without evidence of immunity should receive at least one dose of MMR vaccine.

- Two doses of mumps vaccine gives about 88% protection against disease.

- High vaccination coverage is required to maintain herd immunity and prevent transmission.

- During outbreaks a third dose of MMR vaccine is recommended in high risk groups such as students in hostels or close contact settings.

- Suspected cases should be reported to health authorities for outbreak control.

- Infected persons are isolated for 5 days after onset of parotid gland swelling.

- Droplet precautions and standard precautions are followed in hospital settings.

- Non immune health care workers exposed to mumps virus are excluded from duty from 12th day after exposure to 25th day after last exposure.

- Virus is inactivated by disinfectants such as 1% sodium hypochlorite 70% ethanol glutaraldehyde and formalin.

- t is also destroyed by heat ultraviolet rays and autoclaving.

- Mumps vaccine is contraindicated in pregnancy and pregnancy should be avoided for 4 weeks after vaccination.

- Severely immunocompromised individuals should not receive live vaccine.

- Persons with severe allergy to vaccine components such as neomycin or gelatin should not be vaccinated.

| Symptom or Complication | Affected Organ or System | Frequency/Prevalence | Pathological Description | Clinical Presentation Phase | Diagnostic Markers |

| Parotitis (Inflammation of parotid glands) | Salivary Glands | 95% of clinical symptoms; >70% of total infections; 30%–40% of infected persons (up to 70% bilateral in established cases). | Painful inflammation, submaxillary swelling, and edema; mucosa of Stensen duct often red and swollen. Perivascular and interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration, hemorrhage, and necrosis of acinar and epithelial duct cells. Direct viral destruction of ductal cells with intense lymphocytic infiltration and desquamation. | Early Acute to Established Acute (Glandular Phase) | Elevated serum and urine amylase; RT-PCR of buccal swab; specific IgM antibodies. |

| Orchitis (Testicular inflammation) | Reproductive System (Male) | 10%–40% of post-pubertal males; 30% of unvaccinated and 6% of vaccinated post-pubertal males. | Parenchymal edema, necrosis of seminiferous tubules (germinal epithelium), hyalinization, and perivascular infiltration by lymphocytes. Focal infarcts and potential pressure necrosis leading to fibrosis and atrophy. | Established Acute (typically 1–2 weeks after onset or 3–5 days after parotitis) | Diffuse hyper-vascularity and hydrocele formation on ultrasound; reduced testosterone production; RT-PCR of urine; potential sperm antibodies. |

| Aseptic Meningitis | Central Nervous System (Meninges) | 5%–15% of clinical cases; lower (≤1%) in vaccinated populations. Asymptomatic CSF pleocytosis occurs in up to 50%–60% of cases. | Inflammation of the meninges; viral invasion across the choroid plexus; lymphocytic infiltration. | Established Acute (4–10 days after onset) | CSF pleocytosis (>10 leukocytes/mm3); elevated lymphocyte count and mildly elevated protein; increased cytokine levels; viral isolation from CSF. |

| Pancreatitis | Digestive System (Pancreas) | Approximately 4%–5% of cases; 1% or less in post-vaccine era. | Inflammation causing tissue damage; cellular necrosis; infects human pancreatic beta cells. | Established Acute (late 1st week) | Elevated serum levels of lipase and amylase; clinical symptoms (severe epigastric/upper abdomen pain, nausea). |

| Encephalitis | Central Nervous System (Brain) | Rare; less than 0.5%–1% of cases (approx. 2 per 100,000). | Fluid buildup (edema), congestion, hemorrhage, and damage to myelin sheaths. Lymphocytic perivascular infiltration, perivascular gliosis, and direct viral infection of brain parenchyma leading to necrosis. | Established Acute | MuV RNA in CSF via nested RT-PCR; altered mental status (drowsiness, coma); seizures; CSF analysis. |

| Oophoritis (Ovarian inflammation) | Reproductive System (Female) | Approximately 5%–7% of post-pubertal females; up to 25% in pre-vaccine era; 1% or fewer in vaccinated populations. | Lymphocytic infiltration of ovarian tissue; inflammation causing pelvic pain. | Established Acute | Pelvic pain; clinical examination; lower abdominal pain. |

| Sensorineural Hearing Loss (Deafness) | Auditory System | Approximately 4% (transient high-frequency); permanent loss in <0.01% (1 in 1,000 to 1 in 20,000 cases); typically unilateral (80%). | Damage to the auditory nerve, cochlea, or inner ear structures via CSF or viremia. Lesions and degeneration of stria vascularis, tectorial membrane, and organ of Corti; endolymph inflammation. | Established Acute (may occur without parotitis) to Post-Acute | Clinical hearing assessment; vestibular reactions; transient or permanent deafness. |

| Nephritis / Viruria | Renal System (Kidneys) | Nephritis is rare; viruria (virus in urine) detected in most patients (up to 75%). | Benign involvement or immune complex deposition; interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration, fibrosis, edema, and focal tubular epithelial cell damage. Infection of epithelial cells in distal tubules and calyces. | Early Acute to Established Acute (can persist 14 days post-onset) | Detection of virus in urine via culture or RT-PCR; abnormal renal function tests (rarely severe). |

| Mastitis | Reproductive System (Mammary Glands) | Up to 30% of post-pubertal women; 1% or fewer in vaccinated populations. | Inflammation of the breasts. | Acute | Not in source |

| Prodromal symptoms (Fever, Malaise, Myalgia) | Systemic | Common; fever in 29% of unimmunized; 20%–30% of total infections remain asymptomatic. | Nonspecific inflammatory response following systemic viremia. | Prodromal Phase | Low-grade fever; nonspecific clinical signs. |

| Myocarditis | Cardiovascular System | Rare | Interstitial lymphocytic myocarditis and pericarditis; endocardial fibroelastosis. | Not in source | Electrocardiographic abnormalities. |

| Headache | Central Nervous System | Not in source | Not in source | Prodromal | Not in source |

| Myalgia | Musculoskeletal System | Not in source | Not in source | Prodromal | Not in source |

| Anorexia (Loss of appetite) | Systemic | Not in source | Not in source | Prodromal | Not in source |

FAQ

Q. What is mumps?

A. Mumps is an acute viral infectious disease. It mainly affects salivary glands especially parotid glands. It is a communicable disease caused by mumps virus.

Q. What are the symptoms of mumps?

A. Symptoms include fever headache and body pain. Swelling of parotid glands is the characteristic feature. Pain during chewing and swallowing is seen. Some cases may show mild or no symptoms.

Q. How is mumps spread?

A. Mumps is spread by respiratory droplets. It spreads through coughing sneezing talking and sharing utensils. Close personal contact increases transmission.

Q. What causes mumps?

A. Mumps is caused by mumps virus. It belongs to family Paramyxoviridae. It is an RNA virus.

Q. How long is a person with mumps contagious?

A. A person is contagious from about 2 days before swelling of glands. It remains contagious up to 5 days after onset of parotitis.

Q. What are the complications of mumps?

A. Complications include orchitis oophoritis and pancreatitis. Aseptic meningitis may occur. Hearing loss is rare but possible.

Q. How can mumps be prevented?

A. Mumps can be prevented by vaccination. MMR vaccine is commonly used. Isolation of infected persons also helps in control.

Q. Is there a treatment for mumps?

A. There is no specific antiviral treatment for mumps. Treatment is mainly supportive. Rest hydration and pain relief is advised.

Q. How is mumps diagnosed?

A. Diagnosis is usually based on clinical symptoms. Laboratory tests such as RT-PCR and serology may be used. Swelling of parotid gland supports diagnosis.

Q. How long does it take to show signs of mumps after being exposed?

A. Incubation period of mumps is about 16–18 days. Symptoms may appear between 12 to 25 days after exposure.

Q. Can you get mumps if you are vaccinated?

A. Yes mumps can occur in vaccinated individuals. However disease is usually mild. Vaccination reduces severity and complications.

Q. Who can get mumps?

A. Anyone who is not immune can get mumps. It is more common in unvaccinated individuals. Children adolescents and young adults are commonly affected.

Q. How serious is mumps?

A. Mumps is usually a mild disease. Most people recover completely. Serious complications are uncommon but can occur.

Q. What should you do if you think you have mumps or have been exposed?

A. Medical advice should be taken. Isolation for 5 days after gland swelling is recommended. Inform health authorities if needed.

Q. How common is mumps in the United States?

A. Mumps is now uncommon in United States due to vaccination. Sporadic outbreaks still occur in close contact settings. Most cases are reported among unvaccinated or partially vaccinated groups.

- Brgles, M., Bonta, M., Šantak, M., Jagušić, M., Forčić, D., Halassy, B., Allmaier, G., & Marchetti-Deschmann, M. (2016). Identification of mumps virus protein and lipid composition by mass spectrometry. Virology Journal, 13(9). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-016-0463-0

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Mumps clinical diagnosis fact sheet.

- College of Physicians of Philadelphia. (2022, April 17). Mumps. History of Vaccines.

- Comprehensive analysis of mumps orthorubulavirus: Structure, genomic architecture, replication, and pathogenic mechanisms. (n.d.). [Source material].

- Cui, A., Brown, D. W. G., Xu, W., & Jin, L. (2013). Genetic variation in the HN and SH genes of mumps viruses: A comparison of strains from mumps cases with and without neurological symptoms. PLOS ONE, 8(4), e61791. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061791

- de St. Maurice, A. (2023, May). Mumps. MSD Manual Professional Edition.

- DigiNerve. (2025, May 23). Mumps virus: Characteristics, disease mechanism, and clinical pathology.

- Frost, J. R., Shaikh, S., & Severini, A. (2022). Exploring the mumps virus glycoproteins: A review. Viruses, 14(6), 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14061335

- Galvan, C., Ovsyannikova, I. G., & Kennedy, R. B. (2025). Glycosylation as a strategic mechanism for measles virus and mumps virus immune evasion. Frontiers in Immunology, 16, 1716829. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1716829

- Gouma, S., Koopmans, M. P. G., & van Binnendijk, R. S. (2016). Mumps virus pathogenesis: Insights and knowledge gaps. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 12(12), 3110–3112. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1210745

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. (n.d.). Genus: Orthorubulavirus.

- Jacques, J. P., Hausmann, S., & Kolakofsky, D. (1994). Paramyxovirus mRNA editing leads to G deletions as well as insertions. The EMBO Journal, 13(22), 5496–5503.

- Jahan, T., Akter, K., & Sultana, S. (2020). Virological aspects of mumps: A review. Journal of Monno Medical College, 6(1), 24–27.

- Kolakofsky, D., Roux, L., Garcin, D., & Ruigrok, R. W. H. (2005). Paramyxovirus mRNA editing, the ‘rule of six’ and error catastrophe: A hypothesis. Journal of General Virology, 86(Pt 7), 1869–1877. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.80986-0

- Kubota, M., & Hashiguchi, T. (2021). Unique tropism and entry mechanism of mumps virus. Viruses, 13(9), 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13091746

- Kubota, M., Matsuoka, R., Suzuki, T., Yonekura, K., Yanagi, Y., & Hashiguchi, T. (2019). Molecular mechanism of the flexible glycan receptor recognition by mumps virus. Journal of Virology, 93(15), e00344-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00344-19

- Kubota, M., Takeuchi, K., Watanabe, S., Ohno, S., Matsuoka, R., Kohda, D., … Hashiguchi, T. (2016). Trisaccharide containing α2,3-linked sialic acid is a receptor for mumps virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(41), 11579–11584. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1608383113

- Maganga, G. D., Iroungou, B. A., Bole-Feysot, C., Leroy, E. M., Touré Ndouo, F. S., & Berthet, N. (2014). Complete genome sequence of mumps virus genotype G from a vaccinated child in Franceville, southeastern Gabon, in 2013. Genome Announcements, 2(6), e00972-14. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.00972-14

- Marlow, M., Haber, P., Hickman, C., & Patel, M. (2024, May 1). Mumps. In Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases (Pink Book). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Mumps. (2020). In Wikipedia.

- Mumps virus. (2020). In Wikipedia.

- Mumps virus pathogenesis clinical features [Slides]. (n.d.). [Source material].

- Paterson, R. G., & Lamb, R. A. (1990). RNA editing by G-nucleotide insertion in mumps virus P-gene mRNA transcripts. Journal of Virology, 64(9), 4137–4145.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2024, February). Mumps virus: Infectious substances pathogen safety data sheet.

- Rausch-Phung, E. A., Davison, P., & Morris, J. (2024, May 1). Mumps. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Rima, B., Balkema-Buschmann, A., Dundon, W. G., Duprex, P., Easton, A., Fouchier, R., … Wang, L. (2019). Family: Paramyxoviridae. ICTV Report.

- Rubin, S. A., Sauder, C. J., & Carbone, K. M. (2016, August 11). Mumps virus. Basicmedical Key.

- Rubin, S., Eckhaus, M., Rennick, L. J., Bamford, C. G., & Duprex, W. P. (2015). Molecular biology, pathogenesis and pathology of mumps virus. The Journal of Pathology, 235(2), 242–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4445

- Steele, E. (n.d.). Mumps virus: Structure and function [Video/Lesson]. Study.com.

- UniProt. (n.d.). Mumps orthorubulavirus (MuV).

- Wang, C., Wang, T., Duan, L., Chen, H., Hu, R., Wang, X., … Yang, Z. (2022). Evasion of host antiviral innate immunity by paramyxovirus accessory proteins. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12, 790191. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.790191

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Mumps.

- Xu, P., Luthra, P., Li, Z., Fuentes, S., D’Andrea, J. A., Wu, J., … He, B. (2012). The V protein of mumps virus plays a critical role in pathogenesis. Journal of Virology, 86(3), 1768–1776. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.06019-11