What is mouth pipette?

- A mouth pipette is a laboratory tool historically used to draw liquids into a pipette by creating suction with the mouth. This technique typically involved a glass capillary tube, one end immersed in a liquid and the other placed in the user’s mouth. By sucking on the open end of the pipette, the user reduced air pressure inside the tube, causing the liquid to be drawn up, similar to drinking through a straw.

- The method was widely used in scientific laboratories, particularly before the 1970s, when more advanced mechanical pipettes became available. It was commonly utilized across various disciplines, such as biology and chemistry, where precise liquid measurement was essential. However, mouth pipetting was associated with serious health risks. Users were directly exposed to harmful substances, such as toxic chemicals, biological pathogens, or infectious agents, which could lead to infections or poisoning. Historical records indicate that mouth pipetting was linked to laboratory-acquired infections, such as the case in 1893, where a physician contracted typhoid fever through this practice.

- As mechanical pipettes became more cost-effective and widely accessible in the 1970s, mouth pipetting began to decline. Mechanical pipettes, with their higher accuracy and ability to prevent contamination, replaced mouth pipetting, making it safer and more efficient. Today, the practice is prohibited in most laboratory settings due to safety regulations. Modern alternatives, like mechanical pipette controllers, are now the standard in scientific work, reducing risks and improving reliability.

- Despite the widespread ban in developed nations, there are still reports suggesting that mouth pipetting occurs in some under-resourced laboratories, particularly in developing countries. However, this practice is increasingly rare as global safety standards and access to advanced laboratory equipment continue to improve.

Principle of Mouth Pipette

The working principle of mouth pipetting is based on the creation of a pressure differential, which allows for the movement of liquid into a pipette through suction. This method involves the use of a glass capillary tube, where one end is submerged in the liquid to be transferred, and the other end is placed in the user’s mouth.

To initiate the process, the user creates suction by drawing air through the open end of the pipette. This suction reduces the air pressure inside the tube, causing the atmospheric pressure to push the liquid up into the pipette. As the liquid rises, the user continues to maintain suction until the desired volume is reached. It is essential to control the suction carefully, as excessive pressure could lead to drawing the liquid into the mouth, posing health risks, especially when handling hazardous or infectious substances.

Once the liquid has been drawn into the pipette, the user can transfer it by positioning the pipette over another container. The suction is then released, and gravity, along with atmospheric pressure, causes the liquid to flow out of the pipette and into the target vessel. This process relies on the basic principle of fluid dynamics, where the liquid moves from an area of higher pressure to an area of lower pressure.

While mouth pipetting was once a common practice in laboratories across various fields, such as biology and chemistry, it has become largely obsolete due to its associated health risks. The method exposed users to harmful substances, including toxic chemicals and infectious agents, leading to contamination and potential laboratory-acquired infections. With the advent of mechanical pipettes in the 1970s, which offered greater precision and safety, mouth pipetting was gradually phased out in favor of these more reliable and less hazardous alternatives.

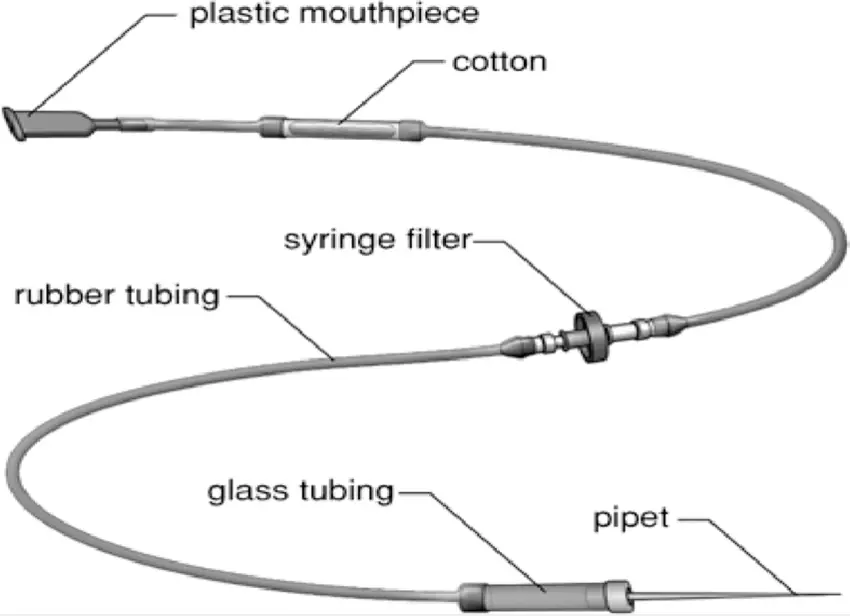

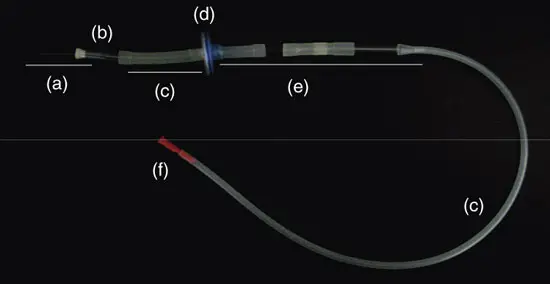

Parts of a Mouth Pipette

Mouth pipettes are made up of several essential components, each serving a specific function in the liquid transfer process. Here’s a breakdown of the key parts:

- Pipette Tube

The pipette tube is a long, narrow glass structure that is open at both ends. The top is slightly wider to accommodate suction, while the bottom is narrower to aid in the precise dispensing of liquids. - Tapered Tip

The tapered tip of the pipette plays a critical role in controlling the flow rate of the liquid. Its pointed design ensures accurate placement of drops, preventing spillage or improper delivery. - Calibration Marks

Along the length of the pipette, there are graduated marks. These marks help users measure specific volumes of liquid, providing an accurate means of transferring substances in controlled amounts. - Upper Opening

This end of the pipette is where suction is applied, usually via the user’s mouth. It is essential for creating the pressure differential that allows liquid to be drawn into the tube. - Rubber Bulb (Optional)

While not a standard feature on traditional mouth pipettes, a rubber bulb may be added. This bulb is used to create suction without the need for mouth suction, reducing the risk of contamination from hazardous substances.

How to Use a Mouth Pipette

Using a mouth pipette requires careful technique to ensure accuracy and prevent contamination. While this method is largely obsolete today due to safety concerns, here’s a guide on how it was traditionally used.

- Preparation

Ensure the pipette is clean and free of contaminants before starting. Choose the solution that needs to be transferred. - Insert the Pipette

Place the tapered end of the pipette into the liquid to be transferred. Ensure that the liquid source is ready. - Create Suction

Insert the open end of the pipette into the mouth.

Gently suck to create suction, drawing the liquid into the pipette. Control the suction carefully to avoid pulling the liquid into the mouth. - Measure the Volume

As the liquid rises, observe the level on the pipette. Ensure the liquid reaches the desired calibration mark for accuracy. - Transfer the Liquid

Move the pipette to the target container, whether it’s a test tube or flask.

Release suction gently to allow the liquid to flow out, using gravity to assist the process. - Final Adjustments

If necessary, reapply suction to fine-tune the volume or adjust the dispensing. - Clean Up

After use, ensure the pipette is thoroughly cleaned and sterilized if it will be reused, to avoid any cross-contamination.

Uses of Mouth Pipette

Mouth pipetting was once a versatile and widely used technique in laboratories. It allowed researchers and technicians to handle a variety of tasks that required precise liquid transfer. However, with the introduction of safer, more accurate mechanical pipettes, the use of mouth pipettes has significantly declined.

- Transferring Liquids

The primary use of mouth pipettes was for transferring small volumes of liquids. This included a wide array of solutions such as water, buffers, and chemical reagents. - Microbial Cultures

Mouth pipetting was frequently employed to handle microbial cultures, including bacteria and yeast. The method allowed researchers to transfer cultures with care, though the associated risk of infection made it a less-than-ideal choice in modern settings. - Blood and Biological Samples

In medical and clinical laboratories, mouth pipettes were sometimes used to collect blood samples or other biological fluids like serum and urine. Despite the risks involved, it served as a practical method for handling specimens before the widespread use of more precise equipment. - Entomology Studies

In the field of entomology, mouth pipettes were occasionally used to collect and transfer small organisms, such as ectoparasites and mosquitoes. This technique was particularly useful in research on disease transmission and ecological studies. - Embryo Handling

In developmental biology and genetics, mouth pipettes were used for delicate tasks, such as handling embryos or performing microinjections. This method allowed for fine control during these precise biological manipulations. - Educational Purposes

Mouth pipetting also had a place in educational environments. It was used as a teaching tool to help students learn liquid handling techniques. This practice was common before the availability of mechanical pipettes that offered greater safety and accuracy. - Historical Laboratory Practices

Before the 1970s, mouth pipetting was a standard practice in laboratories. Mechanical pipettes were not as widely available or affordable, so the mouth pipette became a practical solution for researchers who needed to transfer liquids.

Important Safety Considerations for Mouth Pipetting

Mouth pipetting has significant safety risks, primarily due to the potential for exposure to harmful substances and the lack of precision in handling. These factors make it a practice that is now largely prohibited in laboratory settings.

- Exposure to Hazardous Substances

Mouth pipetting directly exposes the user to toxic chemicals, biological agents, and even radioactive materials. The risk of accidental ingestion or inhalation is high, leading to poisoning or serious illness. - Risk of Infection

Historically, mouth pipetting has been associated with laboratory-acquired infections. Notably, pathogens such as Salmonella and typhoid bacilli were transmitted through oral aspiration. Reports from the late 1800s and early 1900s show a direct link between mouth pipetting and infections, with 17% of laboratory-acquired infections between 1893 and 1950 attributed to this method. - Contamination Risks

Using mouth pipetting can inadvertently introduce respiratory aerosols into the pipetted sample, leading to contamination. This could compromise the integrity of experiments and lead to cross-contamination between different reagents or biological samples. - Inaccurate Volume Measurement

Compared to mechanical alternatives, mouth pipetting lacks precision. The inability to control the volume of liquid accurately can lead to unreliable results and compromised experimental outcomes. - Regulatory Compliance

Most safety guidelines and regulatory bodies prohibit mouth pipetting due to its inherent risks. Laboratory environments are required to implement safer alternatives, such as mechanical pipetting devices, to minimize exposure and improve accuracy. - Historical Incidents

Numerous cases have highlighted the severe health consequences of mouth pipetting. For example, a nursing student was hospitalized after contracting a rare strain of Salmonella in a lab setting where mouth pipetting was still in use.

Drawbacks of Mouth Pipette

Mouth pipetting presents multiple risks, particularly due to health hazards, inaccurate measurements, and contamination concerns. These challenges make it an outdated and unsafe practice, even though it was once common in laboratories.

- Health Risks

Mouth pipetting exposes users directly to toxic chemicals, biological agents, and radioactive materials. The risk of accidental ingestion or inhalation is substantial. These exposures can lead to severe health issues, including poisoning and infections. - Infection Incidents

Mouth pipetting was historically linked to laboratory-acquired infections. A longitudinal study found that between 1893 and 1950, 17% of laboratory infections were due to oral aspiration or splashes into the mouth. This historical data highlights the dangers of using this method. - Inaccuracy in Volume Control

One major issue with mouth pipetting is the difficulty in controlling liquid volumes accurately. The technique relies heavily on the user’s ability to create and maintain the right suction, which can lead to inconsistent measurements and affect the reliability of experimental results. - Sample Contamination

Mouth pipetting introduces the risk of respiratory aerosols contaminating the pipetted sample. This is a particularly serious concern when working with sensitive biological samples or reagents, where even the smallest amount of contamination can compromise results. - Regulatory Non-Compliance

Mouth pipetting is explicitly prohibited in modern laboratories due to its health risks and inaccuracies. Regulatory bodies require the use of mechanical pipettes to eliminate the risk of oral exposure and improve measurement precision. - Historical Prevalence of Accidents

Numerous cases have been documented where laboratory personnel suffered from mouth pipetting. For instance, a nursing student was hospitalized after contracting a Salmonella strain, likely due to this unsafe practice. - Cultural Persistence in Some Regions

Despite the clear risks, some technicians in developing countries continue to use mouth pipetting. This points to a need for improved safety training and better access to modern pipetting equipment.

- https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/suck-it-the-ins-and-outs-of-mouth-pipetting

- https://bodyhorrors.wordpress.com/2013/03/20/mouth_pipetting/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/labrats/comments/11t3a9b/was_mouth_pipetting_actually_a_real_thing_or_is/

- https://www.darkdaily.com/2013/05/10/mouth-pipetting-blogger-reminds-medical-laboratory-technologists-of-an-era-when-this-was-leading-source-of-clinical-laboratory-acquired-infections-510/

- https://www.iacld.com/UpFiles/Documents/295467701.pdf

- https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/109135059700200205

- https://www.gilson.com/pub/media/docs/GuideToPipettingE.pdf

- https://www.integra-biosciences.com/global/en/blog/article/mouth-pipetting-fully-automated-liquid-handlers

- https://www.ase.org.uk/sites/default/files/chemistry%20PDFs/PDFs/Safety%20fillers%20for%20pipettes.pdf

- https://www.scilogex.com/blog/our-blog-1/what-are-the-potential-consequences-if-you-dont-have-a-good-pipetting-technique-6

- https://blog.universalmedicalinc.com/3-safer-alternatives-mouth-pipetting/

- Text Highlighting: Select any text in the post content to highlight it

- Text Annotation: Select text and add comments with annotations

- Comment Management: Edit or delete your own comments

- Highlight Management: Remove your own highlights

How to use: Simply select any text in the post content above, and you'll see annotation options. Login here or create an account to get started.