Hepatitis D, commonly referred to as “delta hepatitis,” is a viral infection of the liver (HDV). Hepatitis D is only transmitted to individuals who are simultaneously infected with the hepatitis B virus. Hepatitis D is transmitted when blood or other body fluids from an infected individual enter the body of an uninfected person. Hepatitis D can manifest as either an acute, short-term infection or a chronic, long-term illness. Hepatitis D can produce severe symptoms and disease, which might result in permanent liver damage or even death. People can become infected with both the hepatitis B and hepatitis D viruses simultaneously (known as “coinfection”), or they might acquire hepatitis D after being infected with hepatitis B (known as “superinfection”). No vaccination exists to prevent hepatitis D. Vaccination against hepatitis B also protects against potential hepatitis D infection.

What is Hepatitis D Virus?

- HDV is the smallest human-infecting virus known to science. HDV is actually a satellite virus of HBV, which provides the envelope proteins necessary for HDV formation.

- As a necessary stage in the formation of HDV virion particles, HDV attracts the HBV envelope proteins; hence, HBV and HDV share the envelope glycoproteins. A second oddity is that HDV has a circular RNA genome that is only 1.7 kb long.

- HDV is the only known animal virus with circular RNA. In this way, HDV is frequently associated with viroids, a plant agent.

- Approximately 15 million individuals worldwide are afflicted with HDV, out of the 240 million infected with its aiding virus HBV. Due to HDV’s need on the presence of HBV envelope proteins, HDV can only develop effective infections in healthy individuals who are coinfected with HBV and HDV.

- HDV can infect persons who are already infected with HBV. Hepatitis D is regarded as one of the most severe forms of viral hepatitis in humans.

- HDV infection frequently exacerbates CHB patients’ liver condition and frequently results in fulminant hepatitis or even liver failure.

- Approximately 5% of CHB carriers also carry HDV. There are presently no specialised antivirals for treating HDV infection, and antivirals for HBV do not improve hepatitis D.

- Certain regions, such as the Middle East and Southern Italy, have a higher incidence of HDV/HBV coinfected people. The HBV vaccine is preventative against HDV infection.

Key facts about Hepatitis D Virus

- Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a virus whose reproduction requires hepatitis B virus (HBV).

- Hepatitis D virus (HDV) infects around 5% of chronic hepatitis B virus carriers worldwide (HBV).

- HDV infection develops when a person has hepatitis B and D simultaneously (co-infection) or hepatitis D after having already contracted hepatitis B. (super-infection).

- Indigenous communities, beneficiaries of haemodialysis, and persons who inject drugs are more likely to be co-infected with HBV and HDV.

- Since the 1980s, the number of HDV infections has dropped globally, primarily due to a successful global HBV immunisation programme.

- The combination of HDV and HBV infection is regarded as the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis due to its accelerated development towards liver-related mortality and hepatocellular cancer.

- Immunization against hepatitis B helps prevent hepatitis D infection, although treatment success rates are low.

Epidemiology of Hepatitis D Virus

- Even though HDV is dependent on HBV, its geographical distribution differs from that of HBV due in part to transmission method differences. HDV is transmitted mostly by parenteral exposure to blood or blood products. While sexual transmission is uncommon (even among homosexual men), vertical transmission is uncommon.

- The majority of HDV epidemiological data has been collected from HBV carriers who are also infected with HDV. It is estimated that approximately 5% of HBV carriers are infected with HDV.

- Recent years have witnessed a dramatic fall in HDV transmission as a result of the declining incidence of HBV infection. This is primarily due to improvements in socioeconomic conditions, awareness of infectious disease transmission, and vaccination rates for hepatitis B.

- HDV is most frequent in the Mediterranean region, East Africa, the Amazon basin, the Middle East, Central and Northern Asia, and certain Pacific regions.

- In Western nations, HDV infection is uncommon and restricted to populations at high risk, such as intravenous drug users, immigrants from highly endemic regions, and recipients of numerous transfusions.

Transmission of Hepatitis D Virus

- As with HBV, HDV is transmitted through broken skin (through injection, tattooing, etc.) or contact with infected blood or blood products. Transmission from mother to offspring is conceivable but uncommon. Vaccination against HBV reduces HDV coinfection; hence, the global incidence of hepatitis D has decreased due to the development of paediatric HBV immunisation initiatives.

- Chronic HBV carriers are susceptible to HDV infection. People who are not immune to HBV (either due to natural disease or vaccination with the hepatitis B vaccine) are susceptible to HBV infection, which increases their chance of HDV infection.

- Indigenous individuals, drug injectors, and those with hepatitis C virus or HIV infection are more likely to be co-infected with HBV and HDV. The risk of co-infection appears to be higher among haemodialysis patients, males who have sex with other men, and commercial sex workers.

Structure of Hepatitis D Virus

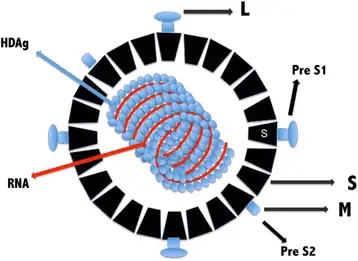

- On the exterior of HDV is a spherical lipoprotein envelope carrying HBsAg. Inside the virion is a ribonucleoprotein containing the viral genome complexed with HDAg.

- The viral genome consists of a 1.7 kb negative-polarity single-stranded circular RNA (ssRNA).

- Due to the high concentration of GC, approximately 74% of the nucleotides complement themselves intramolecularly, may fold into a secondary structure resembling a rod, and are complexed to HDAg.

Delta antigen

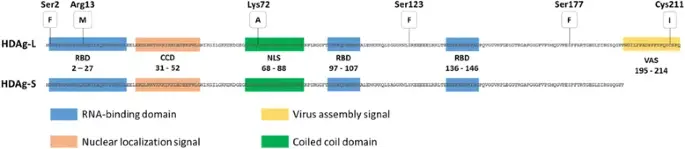

- The single protein encoded by HDV is the Delta (HDAg) antigen, a phosphoprotein that exists in two protein forms: HDAg-S and HDAg-L, with molecular weights of 24 kilodaltons (195 amino acids) and 27 kilodaltons (214 amino acids), respectively. HDAg-S enhances RNA replication whereas HDAg-L promotes HDV RNA enveloping to form the virion, according to studies.

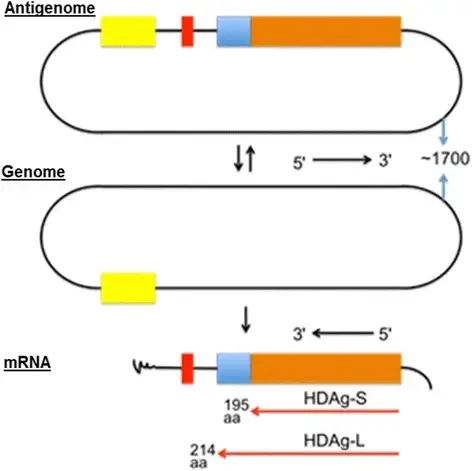

- During the replication cycle, the antigenome undergoes a post-transcriptional modification in which the gene encoding HDAg-S is modified by an enzyme known as Adenosine Deaminase (ADAR1), a host protein, by substituting an adenine for an inosine and indirectly exchanging the UAG-stop codon for a UGG-tryptophan, known as the Amber/W site, which will give rise to the gene.

- The C-terminal portion of HDAg-L contains 19 extra amino acids, which distinguishes it from HDAg. Multiple functional domains are shared by both HDAg isoforms, including the RNA-binding domain (RBD), a nuclear localization signal (NLS), a coiled coil domain (CCD), and a proline- and glycine-rich C-terminal region. The 19 extra amino acids of HDAg-L constitute a virus assembly signal (VAS), a highly variable and genotype-specific sequence. It acts as a binding site interacting with HBsAg/membrane, which is important to virus assembly.

- HDAg undergoes further post-transcriptional changes, including phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, and isoprenylation in the case of HDAg-L. HDAg subcellular localization and RNA replication were correlated with the methylation of Arg13, acetylation of Lys72, and phosphorylation of Ser177 and Ser123. The majority of these modifications are crucial for the roles of HDAg-S in HDV RNA replication, which acts by directly boosting the elongation of transcription via the substitution of the transcription repressor elongation factor connected to RNA polymerase II.

HDV RNA

- Replication of the genome is entirely driven by RNA, i.e., all the synthesis of new RNA uses HDV RNA as its template, with no intermediate DNA template. In hepatocytes, HDV synthesises antigenome, which is complementary RNA, from its genome.

- This activity is an absolute need for viral RNA replication; the genome and antigenome each contain one ribozyme domain with approximately 85 nucleotides that are capable of self-cleaving and self-binding.

Viral replication of HDV

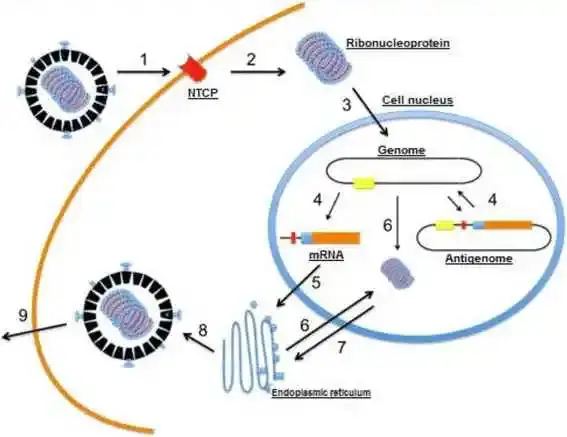

- The virion sticks to hepatocytes by an interaction between HbsAg-L and an uncharacterized membrane receptor in the host cell.

- the virion penetrates the cell and loses its envelope.

- The ribonucleoprotein (HDV RNA complexed with HDAg) is transported into the nucleus of the cell;

- genomic RNA is transcribed in the nucleus into mRNA and antigenomic RNA, which serves as a template for new RNA genomic transcripts.

- The mRNA is exported to the cytoplasm, where it is translated into HDAg-S in the endoplasmic reticulum;

- the newly formed HDAg-S molecules then return to the nucleus to assist the synthesis of additional RNA. The two forms of HDAg combine with the new genomic RNA to generate new ribonucleoproteins.

- which are then transported to the cytoplasm, where they interface with HBV envelope proteins via HDAg-L in the endoplasmic reticulum to form new viral particles.

- By budding in an intermediate compartment.

- these particles are exported from the hepatocyte via the trans-Golgi network in order to reinfect new cells.

Pathogenesis of HDV

- Even though the pathophysiology of HDV infection is still poorly understood, it is dependent on two major mechanisms: direct cytotoxicity in the acute phase and immune-mediated hepatitis in the chronic phase.

- Typically, the HDV infection is not immediately cytopathic. Large amounts of S-HDAg or HDV RNA synthesis are only directly harmful to the hepatocyte membrane in extreme cases, resulting in cell death.

- In the chronic phase, inflammatory cells encircle hepatocytes, and numerous autoantibodies (e.g., liver-kidney-microsomal type 3 antibodies) have been discovered, suggesting an immunopathogenic involvement.

- In addition, the interaction between HDV and HBV affects the natural progression: a chronic HDV infection might inhibit HBV multiplication, resulting in HBeAg and HBsAg seroclearance.

- On the other hand, serum HBV DNA persistence increases the risk of liver disease progression.

Clinical significance of HDV

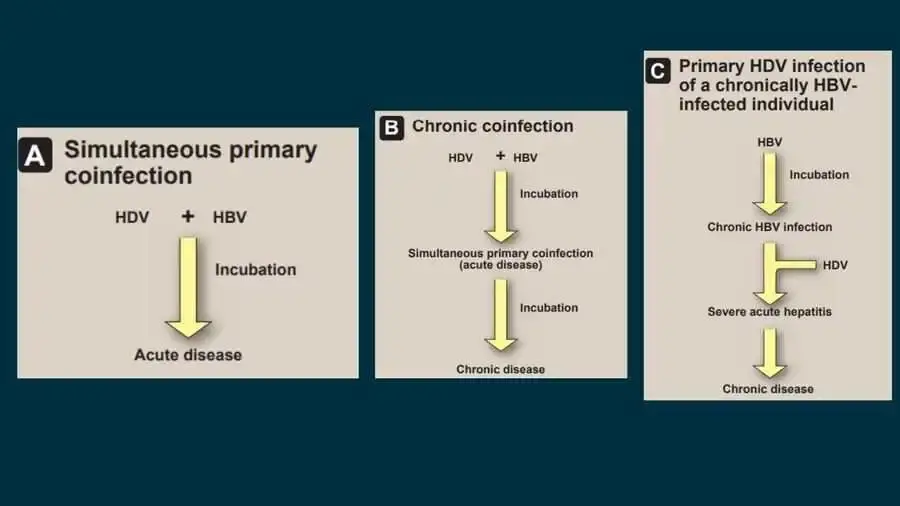

- HDV illness can manifest in one of three forms: First, simultaneous primary coinfection with HBV and HDV can generate an acute illness identical to that caused by HBV alone, with the exception that, depending on the relative concentrations of the two agents, two episodes of acute hepatitis may occur in succession.

- In addition, the risk of deadly fulminant hepatitis induced by HDV is significantly higher than with HBV alone. The probability of progression to the second form of HDV illness (chronic coinfection with HBV) is also significantly elevated.

- Cirrhosis and HCC, as well as liver failure-related mortality, occur more commonly than with HBV infection alone.

- The third variation, primary HDV infection of a chronically HBV-infected individual, results in severe acute hepatitis after a brief incubation time and, in over 70% of instances, chronic HDV infection. Again, the chance of acute hepatitis becoming fulminant is substantially raised in this circumstance, and the persistent infection is frequently of the severe chronic variety.

Diagnosis of HDV

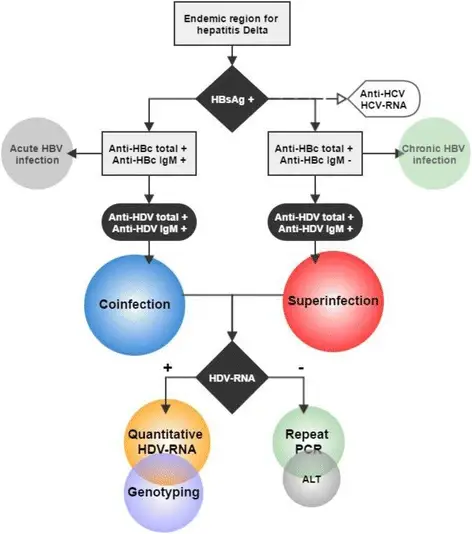

- HDV antibody (anti-HDV) is the serological marker of HDV infection and can be tested via radioimmunoassay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. IgM anti-HDV, which corresponds to contemporaneous hepatic necroinflammation and predicts disease progression56 or remission of chronic HDV infection, is the most important diagnostic marker for active HDV infection.

- IgM anti-HDV is not indicative of acute HDV infection as it is with hepatitis A or B, as the titer is frequently elevated in patients with persistent chronic HDV infection.

- Using IgM anti-HBc, one may differentiate between patients with coinfection and superinfection: in HBsAg-positive individuals, the presence of both IgM anti-HBc and IgM anti-HDV supports HDV–HBV coinfection, whereas the presence of IgM anti-HDV alone suggests a superinfection with HDV.

- Low levels of HDV antigenemia can be detected using a radiolabeled Western blot antibody. In addition, the real-time reverse transcription PCR technique may detect HDV viremia at concentrations as low as 100 copies per millilitre.

- In the chronic phase, the serum HDV RNA level is related with liver damage and higher ALT levels. The presence of HDAg in the nuclei of hepatocytes is the gold standard for diagnosing chronic HDV infection, and liver biopsies continue to be the most definitive approach for assessing disease severity.

Treatment of HDV

- There is no treatment available for HDV infection. Due to the fact that HDV requires co-infection with HBV, strategies for preventing HBV infection are also helpful for preventing HDV infection.

- There is no HDV-specific vaccination available. Those who are persistently infected with HBV can only be safeguarded from HDV by reducing exposure opportunities. Those who are protected from HBV infection through vaccination are not susceptible to HDV.

Prevention of HDV

- Because hepatitis D virus requires hepatitis B virus to proliferate, the hepatitis B vaccine offers protection against hepatitis D virus. [37][38]

- In the absence of a vaccine against delta virus, risk groups must receive the HBV vaccine shortly after delivery.

- (Reference needed)

- Although the effectiveness of latex condoms in preventing HBV is questionable, they may potentially assist reduce the transmission rate.

- Women who are pregnant or trying to conceive can undergo a blood test for HBV to determine in advance whether or not the newborn should get HBIG (hepatitis B immune globulin) and a vaccine.

- Patients with hepatitis B may choose to avoid tattoos and piercings, as needles are a transmission pathway. This also applies to patients who take injectable medicines. Entering a treatment programme or refraining from sharing needles or other instruments with others may be advantageous for reducing transmission risk.

References

- Masood U, John S. Hepatitis D. [Updated 2022 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470436/

- Botelho-Souza, L.F., Vasconcelos, M.P.A., dos Santos, A.d. et al. Hepatitis delta: virological and clinical aspects. Virol J 14, 177 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-017-0845-y

- Turon-Lagot, Vincent & Saviano, & Schuster, Catherine & Baumert, & Verrier, Eloi. (2020). Targeting the Host for New Therapeutic Perspectives in Hepatitis D. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9. 222. 10.3390/jcm9010222.

- Abbas Z, Afzal R. Life cycle and pathogenesis of hepatitis D virus: A review. World J Hepatol. 2013 Dec 27;5(12):666-75. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i12.666. PMID: 24409335; PMCID: PMC3879688.

- Ryu, W.-S. (2017). Hepatitis Viruses. Molecular Virology of Human Pathogenic Viruses, 319–334. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-800838-6.00023-0

- Chen, D.-S., & Chen, P.-J. (2011). Hepatitis B and Deltavirus Infections. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice, 433–440. doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-3935-5.00066-5

- Louten, J. (2016). Hepatitis Viruses. Essential Human Virology, 213–233. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-800947-5.00012-0

- https://viralzone.expasy.org/175

- https://www.news-medical.net/health/What-is-Hepatitis-D.aspx

- https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hdv/index.htm#:~:text=Hepatitis%20D%20only%20occurs%20in,long%2Dterm%2C%20chronic%20infection.

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-d