What is Digastric Muscle?

- The digastric muscle, scientifically termed as “digastricus,” is a distinctive bilaterally paired suprahyoid muscle situated beneath the jaw. Characterized by its dual ‘bellies’—an anterior and a posterior section—this muscle plays a pivotal role in various oral and pharyngeal functions.

- The anterior belly originates from the digastric fossa of the mandible, while the posterior belly extends from the mastoid notch of the temporal bone. These two bellies converge at an intermediate tendon, which is anchored to the hyoid bone, a unique arrangement that facilitates a pulley-like action on the jaw.

- In terms of innervation, the anterior belly receives signals via the mandibular nerve (cranial nerve V), whereas the posterior belly is innervated by the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII).

- Functionally, the digastric muscle is integral to actions such as chewing, speaking, and breathing. It can either act to depress the mandible, facilitating mouth opening, or elevate the hyoid bone, aiding in swallowing.

- The nomenclature “digastric” is derived from the Greek word “dis,” signifying “double,” and the Latin term “gaster,” meaning “belly.” This etymology aptly describes the muscle’s bifurcated structure. While there are other muscles in the human anatomy with two bellies, such as the occipitofrontal and omohyoid, the term “digastric muscle” is exclusively reserved for this specific muscle due to its prominent role and unique configuration.

- Furthermore, the digastric muscle is associated with the suprahyoid aponeurosis, a broad connective tissue layer that extends from its tendon on each side, connecting to the body and the larger cornu of the hyoid bone. It’s noteworthy that anatomical variations can occur, leading to atypical digastric muscles, which may be congenital in nature.

- In conclusion, the digastric muscle, with its dual-bellied structure, plays a crucial role in various oral and pharyngeal functions, underscoring its significance in human anatomy and physiology.

Digastric Muscle Definition

The digastric muscle is a bilaterally paired suprahyoid muscle located beneath the jaw, characterized by two distinct ‘bellies’—an anterior and a posterior section—that play pivotal roles in jaw movement and swallowing.

Characteristics of Digastric Muscle

The digastric muscle exhibits several distinctive characteristics:

- Dual Bellies: The muscle is bifurcated into two ‘bellies’—an anterior belly and a posterior belly.

- Location: It is a suprahyoid muscle situated beneath the jaw.

- Origins and Attachments:

- The anterior belly originates from the digastric fossa of the mandible.

- The posterior belly extends from the mastoid notch of the temporal bone.

- Both bellies converge at an intermediate tendon anchored to the hyoid bone.

- Innervation:

- The anterior belly is innervated by the mandibular nerve (cranial nerve V).

- The posterior belly receives its innervation from the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII).

- Function:

- The muscle aids in depressing the mandible, facilitating mouth opening.

- It also plays a role in elevating the hyoid bone, assisting in swallowing and speaking.

- Etymology: The term “digastric” is derived from Greek and Latin roots, with “dis” meaning “double” and “gaster” meaning “belly,” aptly describing its two-bellied structure.

- Association with Other Structures: The digastric muscle is associated with the suprahyoid aponeurosis, a broad layer of connective tissue.

- Anatomical Variations: Some individuals may exhibit atypical or abnormal digastric muscles, which can be congenital in nature.

Where is the Digastric Muscle Located?

The digastric muscle is located in the neck and extends from the lower jaw (mandible) to the skull. It consists of two muscular bellies: the anterior belly and the posterior belly, connected by an intermediate tendon.

- Anterior Belly: It originates from the digastric fossa of the mandible, which is near the midline at the base of the mandible. From there, it extends downward and backward to the intermediate tendon.

- Posterior Belly: It originates from the mastoid notch of the temporal bone, located on the inferior surface of the skull, medial to the mastoid process. It then extends anteroinferiorly to join the intermediate tendon.

The intermediate tendon, situated between the two bellies, is connected to the body of the hyoid bone. This muscle plays a role in various actions, including depressing the mandible (opening the mouth) and elevating the hyoid bone during swallowing and speaking.

Digastric Muscle Structure or Anatomy

The digastric muscle, an integral component of the suprahyoid group of muscles, is uniquely characterized by its bifurcated structure, comprising two muscular bellies connected by an intermediate tendon. This anatomical arrangement is distinct, with the posterior belly being notably longer than its anterior counterpart.

Embryological Origins and Innervation: The digastric muscle’s dual bellies have distinct embryological derivations. The anterior belly originates from the first brachial arch, while the posterior belly emerges from the second brachial arch. This difference in embryological origins translates to their varied innervation patterns. Specifically, the anterior belly is innervated by the mylohyoid nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V3). In contrast, the posterior belly receives its innervation from the digastric branch of the facial nerve (CN VII).

Structural Details:

1. Posterior Belly of Digastric Muscle

This belly anchors itself at the mastoid notch of the temporal bone, an anatomical feature situated on the skull’s inferior surface. From this point, it extends in an anteroinferior direction towards the intermediate tendon.

- The posterior belly of the digastric muscle originates from the mastoid process of the temporal bone, a distinct bony prominence situated posterior to the ear. From this point, the muscle extends in an anteroinferior direction, navigating through the anatomical region known as the carotid triangle, before converging with the intermediate tendon.

- This intermediate tendon, a pivotal structure within the digastric muscle, is formed by the amalgamation of the muscle’s two bellies. As the posterior belly progresses from the mastoid process towards the mandible, it transitions into this tendon, which subsequently courses through a tendinous pulley associated with the hyoid bone. This unique arrangement facilitates the muscle’s role in various jaw and neck movements.

- Embryologically, the genesis of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle is linked to the second pharyngeal arch. This arch is one among the series of six embryonic structures responsible for shaping the intricate anatomy of the head and neck. The posterior belly’s association with this arch underscores its evolutionary and developmental significance in human anatomy.

2. Anterior Belly of Digastric Muscle

Originating from the digastric fossa of the mandible, this belly progresses in an inferoposterior trajectory to meet the intermediate tendon.

- The anterior belly of the digastric muscle originates from a specific depression known as the digastric fossa, located on the inner aspect of the mandible’s lower border. Positioned near the symphysis, this fossa serves as the anchoring point for the anterior belly, which extends in a downward and backward direction from its point of attachment.

- From a neurological perspective, the anterior belly derives its innervation from the trigeminal nerve, specifically via the mylohyoid nerve. Notably, the mylohyoid nerve is a subsidiary branch of the inferior alveolar nerve. The embryological development of the anterior belly can be attributed to the first pharyngeal arch, highlighting its evolutionary significance in the anatomy of the human jaw and neck region.

- In essence, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle plays a pivotal role in the biomechanics of the jaw, with its unique origin and innervation pattern underscoring its importance in various physiological functions.

3. Intermediate Tendon

This tendon serves as the confluence point for both bellies. Interestingly, it perforates the stylohyoideus muscle and is encased within a fibrous loop that connects to the hyoid bone’s body and greater cornu. Occasionally, this tendon may be enveloped by a synovial sheath.

- The intermediate tendon, an integral component of the digastric muscle, serves as a robust fibrous connector between the muscle’s anterior and posterior bellies. This tendon, characterized by its strength and flexibility, is embedded within the hyoid fascia, a specialized fibrous connective tissue loop situated in the neck region.

- Functionally, the intermediate tendon acts as a pivotal point, enabling the coordinated action of the digastric muscle’s two bellies. This coordination is essential for various physiological activities, including the elevation of the hyoid bone and the depression of the mandible, processes vital for actions such as swallowing and vocalization.

- Furthermore, the intermediate tendon plays a pivotal role in stabilizing and maintaining the hyoid bone’s position, especially during dynamic movements of the head and neck. This stabilization ensures the bone remains anchored, providing a stable base for the associated muscles and structures.

- However, the intermediate tendon is not immune to injuries or pathological conditions. Damage or stress to this tendon can manifest in a spectrum of symptoms, ranging from difficulty in swallowing and hoarseness to localized pain in the neck or jaw region. Such injuries might arise from muscular strain, trauma, or even underlying medical conditions, including infections or malignancies.

- In conclusion, the intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle is a fundamental structure, ensuring the harmonious function of the muscle and facilitating essential physiological processes in the neck region. Proper care and attention to this tendon are crucial for maintaining optimal neck and jaw functionality.

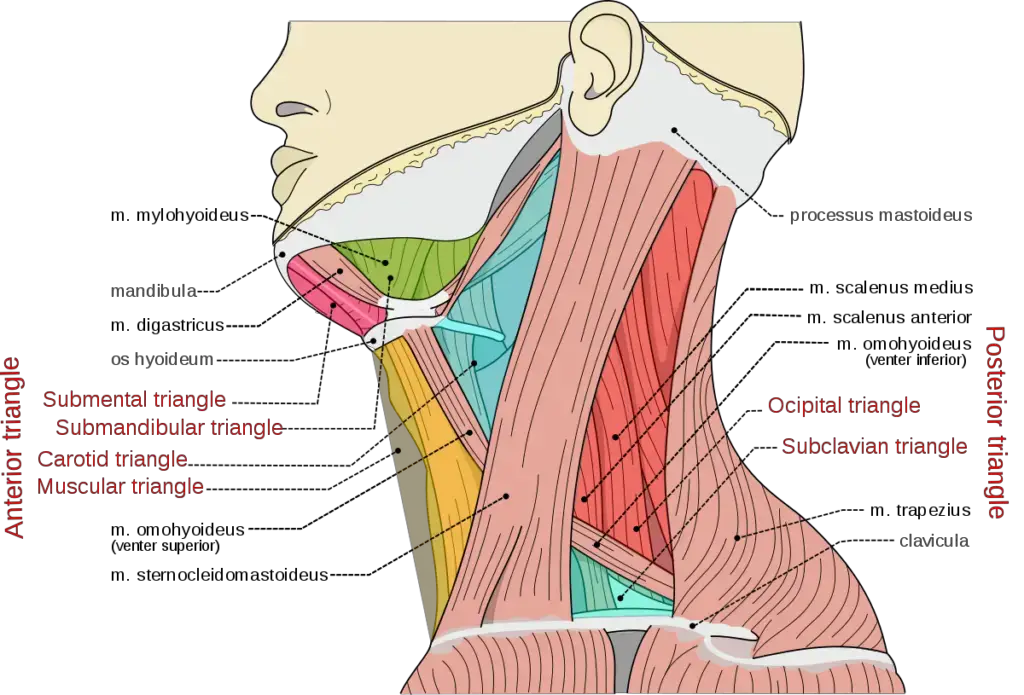

Anatomical Relations: The digastric muscle’s posterior belly is positioned posteriorly to both the parotid gland and the facial nerve. Furthermore, this muscle demarcates the anterior triangle of the neck, subdividing it into four smaller triangles: the submandibular, carotid, submental, and inferior carotid triangles.

Variations: Anatomical variations in the digastric muscle are not uncommon. The intermediate tendon might be absent in some individuals. The posterior belly could exhibit variations in its origin, sometimes arising from the styloid process of the temporal bone or even connecting to the pharyngeal constrictor muscles. The anterior belly might occasionally be bifurcated, exhibit additional muscle slips, or even fuse with the mylohyoid muscle.

Functional Role: Functionally, the digastric muscle plays a dual role. When the hyoid bone is stabilized by the infrahyoid muscles, the digastric muscle acts to depress the mandible. Conversely, it can also elevate the hyoid bone, facilitating actions like swallowing.

In summary, the digastric muscle, with its dual-bellied structure and intricate anatomical relations, plays a pivotal role in oral and pharyngeal functions. Its unique embryological origins and innervation patterns further underscore its significance in human anatomy.

Triangles of Digastric Muscle

The digastric muscle, an integral component of the suprahyoid group of muscles, delineates several anatomical triangles within the neck region. These triangles, formed by the muscle’s unique positioning and its interaction with other structures, are pivotal in understanding the anatomy and vascular distribution of the neck.

- Submandibular or Digastric Triangle: Situated just beneath the mandible, this triangle is demarcated by the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle and the mandible’s inferior border. Within this triangle, one can find essential structures such as the submandibular gland, submandibular lymph nodes, hypoglossal nerve, facial artery, and facial vein (Kim & Loukas, 2019).

- Superior Carotid or Carotid Triangle: This triangle’s boundaries are defined by the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the trapezius muscle’s anterior border. It encompasses a significant portion of the neck’s vascular structures.

- Submental Triangle: Positioned centrally below the chin, this triangle is bordered laterally by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. Medially, it is confined by the neck’s midline, and its inferior limit is the hyoid bone. This triangle primarily houses structures related to the floor of the mouth and the anterior neck region.

- Inferior Carotid or Muscular Triangle: Located in the neck’s anterior section, its boundaries are set by the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the omohyoid muscle, and the anterior border of the trapezius muscle. This triangle encompasses various muscular and vascular structures vital for neck mobility and blood supply.

In summary, the digastric muscle’s strategic positioning and its interaction with neighboring anatomical structures create these distinct triangles. Each of these triangles houses specific vascular, muscular, and neural components, making them essential landmarks in clinical and surgical procedures involving the neck.

Action of Digastric Muscle

The digastric muscle is a complex muscle located in the neck, and it consists of two muscle bellies: the anterior belly and the posterior belly. These two bellies are connected by an intermediate tendon. The digastric muscle plays a pivotal role in several actions:

- Depression of the Mandible: When both the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle contract, they work to depress the mandible (lower the jaw). This action assists in opening the mouth.

- Elevation of the Hyoid Bone: The digastric muscle, when it contracts, can also elevate the hyoid bone. This action is particularly important during swallowing.

- Stabilization of the Hyoid Bone: During actions like speaking and swallowing, where other muscles are working to depress the hyoid bone, the digastric muscle acts to stabilize the hyoid, preventing its downward movement.

It’s worth noting that the digastric muscle doesn’t work in isolation for these actions. It collaborates with several other muscles in the neck and jaw region to facilitate coordinated movements, especially during complex actions like speaking, chewing, and swallowing.

Digastric Muscle Lump

A lump or swelling in the region of the digastric muscle can be concerning for individuals who discover it. While the presence of a lump does not always indicate a serious condition, it’s essential to understand potential causes and when to seek medical attention:

- Lymphadenopathy: Swollen lymph nodes can sometimes be felt in the submandibular region, which is near the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. Lymph nodes can enlarge due to infections, inflammation, or less commonly, malignancies.

- Submandibular Salivary Gland Enlargement: The submandibular salivary gland is located near the digastric muscle. Conditions like sialadenitis (inflammation of the salivary gland), salivary gland stones, or tumors can cause enlargement of this gland.

- Muscle Strain or Spasm: Occasionally, a muscle strain or spasm can cause a palpable thickening or lump-like feeling, although this is less common with the digastric muscle.

- Branchial Cleft Cyst: This is a congenital lesion that can present as a lump in the neck. It arises from embryonic remnants and can sometimes be located near the digastric muscle.

- Lipoma: A lipoma is a benign fatty tumor that can occur anywhere in the body, including the neck region.

- Thyroglossal Duct Cyst: This is another congenital lesion that can present as a midline neck lump, usually moving upwards with swallowing or protrusion of the tongue.

- Other Tumors or Growths: Less commonly, other benign or malignant tumors can present as lumps in the neck region.

If you or someone you know discovers a lump in the region of the digastric muscle or anywhere in the neck, it’s essential to consult with a healthcare professional for a proper evaluation. They can provide an accurate diagnosis and recommend appropriate treatment or management strategies.

Digastric Muscles Variations

The digastric muscle, a vital component of the human neck and jaw anatomy, exhibits a range of anatomical variations. These variations, while not common in every individual, provide insights into the diversity and adaptability of human musculature.

- Anterior Belly Variations:

- Duplication: In some instances, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle may manifest in a duplicated form.

- Extra Slips: The anterior belly can give rise to additional muscular extensions, known as slips, which may extend towards the jaw or the mylohyoid muscle. These slips can sometimes cross over and intertwine with a corresponding slip from the opposite side.

- Absence: In rare cases, the anterior belly might be entirely absent. In such scenarios, the posterior belly compensates by attaching directly to the hyoid bone or the mid-region of the jaw.

- Tendon Positioning:

- The intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle, which connects its anterior and posterior bellies, typically lies in close proximity to the stylohyoid muscle. Variations in its positioning can occur:

- Anterior Positioning: The tendon may occasionally be situated anterior to the stylohyoid muscle.

- Posterior Positioning: Although exceedingly rare, there are instances where the tendon is positioned posterior to the stylohyoid muscle.

- The intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle, which connects its anterior and posterior bellies, typically lies in close proximity to the stylohyoid muscle. Variations in its positioning can occur:

- Mentohyoideus Muscle:

- This is an additional muscle that may be present in some individuals. It extends from the body of the hyoid bone, reaching up to the chin. Its presence signifies another variation associated with the digastric muscle’s anatomical region.

In summary, the digastric muscle’s anatomical variations underscore the complexity and adaptability of human musculature. While the standard structure serves most individuals, these variations highlight the body’s ability to adapt and function efficiently despite deviations from the typical anatomy.

Digastric Muscle Swollen

Swelling or enlargement of the digastric muscle or the area around it can be due to various causes. Here are some potential reasons for swelling in the region of the digastric muscle:

- Muscle Strain or Injury: Overuse, trauma, or strain to the digastric muscle can lead to inflammation and swelling.

- Infections: Infections in the neck region, especially in the submandibular space or lymph nodes, can cause swelling. This might be accompanied by pain, redness, and warmth.

- Lymphadenopathy: Enlarged lymph nodes in the submandibular region can be mistaken for digastric muscle swelling. Causes include infections, inflammatory conditions, or malignancies.

- Submandibular Salivary Gland Issues: Disorders of the submandibular salivary gland, such as sialadenitis (inflammation), sialolithiasis (stones in the salivary gland), or tumors, can cause swelling in the area.

- Cysts: Branchial cleft cysts or thyroglossal duct cysts can present as swellings in the neck and might be located near the digastric muscle.

- Tumors: Benign or malignant tumors in the neck region can cause swelling. For instance, lipomas (benign fatty tumors) can develop in the neck.

- Other Inflammatory Conditions: Conditions like autoimmune disorders can sometimes manifest with neck swelling.

- Post-Surgical or Post-Procedural Swelling: If someone has recently undergone a procedure or surgery in the neck region, swelling might be a post-operative symptom.

If there’s swelling in the region of the digastric muscle or any other part of the neck, it’s crucial to seek medical evaluation. A healthcare professional can provide a proper assessment, determine the cause of the swelling, and recommend appropriate treatment.

Digastric Muscle Pain

- The digastric muscle, a prominent component of the suprahyoid group of muscles, plays a crucial role in various oral and pharyngeal functions. However, it is also frequently implicated as a potential source of discomfort in individuals presenting with pain in the jaw, throat, facial region, and even the teeth.

- This muscle’s unique anatomy, characterized by its bifurcated structure with each belly receiving innervation from distinct cranial nerves, makes it susceptible to tension. The anterior belly is innervated by the trigeminal nerve, while the posterior belly receives its innervation from the facial nerve. These nerves have different distributions across the face and jaw, leading to a complex pain presentation.

- Tension or strain in the anterior belly can manifest as pain in areas served by the trigeminal nerve, while tension in the posterior belly can produce discomfort in regions connected to the facial nerve. Consequently, pain originating from the digastric muscle can radiate to various parts of the face and jaw, often making it challenging to pinpoint the exact source of discomfort.

- It’s essential to recognize that pain sensations stemming from the anterior and posterior bellies might differ due to their distinct innervation patterns. This can sometimes lead to misdiagnosis or misinterpretation of the pain’s origin.

- To alleviate the discomfort associated with digastric muscle tension, certain therapeutic interventions can be beneficial. Simple jaw exercises and gentle massages targeting the muscle can help relax it, subsequently reducing the pain. Even if the pain seems to be emanating from a different region, addressing the digastric muscle can often provide significant relief, underscoring the interconnected nature of facial musculature and innervation.

Digastric Muscle Cramp

A cramp in the digastric muscle, like cramps in other muscles, refers to a sudden, involuntary contraction of the muscle that can cause pain or discomfort. While cramps are more commonly associated with muscles in the limbs, such as the calf or thigh, it is possible for muscles in the neck, including the digastric muscle, to experience tension or spasm. Here are some potential causes and considerations regarding a cramp in the digastric muscle:

- Muscle Strain: Overuse or strain, especially from activities that involve excessive or repetitive jaw movements, can lead to muscle tension or spasms in the digastric muscle.

- Dehydration: Dehydration can lead to muscle cramps in various parts of the body, including the neck.

- Electrolyte Imbalance: An imbalance of electrolytes such as potassium, calcium, or magnesium can contribute to muscle cramps.

- Poor Posture: Maintaining a poor posture, especially while working or using electronic devices, can strain the neck muscles, leading to spasms or discomfort.

- Injury: Trauma or injury to the neck or jaw region can result in muscle spasms or tension.

- Dental Issues: Problems with the teeth or jaw alignment can sometimes lead to tension in the muscles involved in jaw movement, including the digastric muscle.

- Other Medical Conditions: Certain medical conditions, such as dystonia, can cause involuntary muscle contractions in various parts of the body.

- Medications: Some medications have side effects that can cause muscle cramps or spasms.

If someone experiences persistent or recurrent cramps in the digastric muscle or any other unusual symptoms, it’s essential to consult with a healthcare professional. They can provide a proper assessment, determine the underlying cause, and recommend appropriate interventions or treatments.

Digastric Muscles of Other Animals

The digastric muscle, while commonly studied in the context of human anatomy, is also a significant component in the musculature of various animal species, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. Its presence across such diverse taxa underscores its evolutionary importance and functional relevance.

- Mammals: In the majority of mammalian species, the digastric muscle mirrors its human counterpart in structure, comprising two distinct bellies. These bellies originate from separate anatomical locations and converge at the hyoid bone. This muscle plays a pivotal role in facilitating jaw movements, aiding in processes like mastication and swallowing.

- Reptiles: Reptilian anatomy showcases a digastric muscle that, while functionally analogous to the mammalian version, is typically less pronounced. Given the relatively rudimentary jaw structures of reptiles, their digastric muscle doesn’t necessitate the same degree of development as seen in mammals. Despite its reduced complexity, the muscle remains integral to fundamental actions like jaw movement and swallowing in these creatures.

- Birds: Avian anatomy presents a unique rendition of the digastric muscle. In birds, this muscle is partitioned into three distinct segments: anterior, posterior, and intermediate bellies. While the anterior and posterior bellies retain functions akin to their mammalian counterparts, the intermediate belly extends from the posterior segment, anchoring itself to the sternum. This specialized configuration not only facilitates beak movements and swallowing but also aids in the elevation of the sternum during respiratory and flight activities. The intricate arrangement of these muscle bellies around the avian skull underscores the digastric muscle’s adaptability and significance in meeting the specific physiological demands of birds.

In summation, the digastric muscle’s presence and variations across different animal groups highlight its evolutionary adaptability and functional significance. Whether in mammals with their intricate jaw movements, reptiles with their simpler oral structures, or birds with their specialized respiratory and feeding mechanisms, the digastric muscle remains a cornerstone of vertebrate anatomy.

Digastric Muscle Function

The digastric muscle, a component of the suprahyoid group of muscles, serves several critical functions related to oral and pharyngeal activities:

- Jaw Opening: The digastric muscle aids in depressing the mandible, facilitating the opening of the mouth.

- Swallowing: By elevating the hyoid bone and stabilizing it during the act of swallowing, the digastric muscle ensures smooth passage of food and liquids down the throat.

- Speaking: The muscle plays a role in articulation and speech production by assisting in the movement and stabilization of the jaw and hyoid bone.

- Chewing: In conjunction with other muscles of mastication, the digastric muscle contributes to the complex process of chewing, allowing for the breakdown of food.

- Breathing: While not its primary function, the digastric muscle assists in certain breathing actions, especially those that involve movements of the mouth and throat.

- Lateral Jaw Movements: Due to its unique pulley-like mechanism at the hyoid bone, the digastric muscle can produce forces that enable side-to-side movements of the jaw.

In summary, the digastric muscle’s multifaceted functions underscore its significance in ensuring the efficient performance of various oral and pharyngeal actions.

FAQ

What is the digastric muscle?

The digastric muscle is a muscle located in the neck, consisting of two bellies (anterior and posterior) connected by an intermediate tendon.

Where is the digastric muscle located?

The digastric muscle extends from the lower jaw (mandible) to the skull, with the anterior belly originating from the mandible and the posterior belly from the mastoid notch of the temporal bone.

What is the function of the digastric muscle?

The digastric muscle plays a role in depressing the mandible (opening the mouth) and elevating the hyoid bone during activities such as swallowing and speaking.

How is the digastric muscle innervated?

The anterior belly is innervated by the mylohyoid nerve (a branch of the trigeminal nerve), while the posterior belly is innervated by the facial nerve.

Why is it called the “digastric” muscle?

The term “digastric” refers to the muscle’s two distinct bellies, with “di-” meaning “two” and “-gastric” referring to “belly” or “muscle.”

Can the digastric muscle cause pain?

Yes, tension or strain in the digastric muscle can lead to symptoms such as jaw, throat, tooth, and facial pain.

How is digastric muscle pain treated?

Treatment may include relaxation techniques, physical therapy, light massage, and exercises to relieve tension in the muscle.

What are the triangles associated with the digastric muscle?

The digastric muscle divides the anterior triangle of the neck into smaller triangles, including the submandibular (or digastric) triangle, carotid triangle, submental triangle, and muscular triangle.

Are there variations in the digastric muscle?

Yes, variations can include the absence of the anterior belly, duplication of the anterior belly, or the presence of extra muscle slips.

Do other animals have a digastric muscle?

Yes, the digastric muscle is present in various animals, including mammals, reptiles, and birds, though its structure and function may vary across species.

References

- Biology Dictionary. (n.d.). Digastric muscle. Retrieved from https://biologydictionary.net/digastric-muscle/

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Digastric muscle. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digastric_muscle

- Biology Online. (n.d.). Digastric muscle. Retrieved from https://www.biologyonline.com/dictionary/digastric-muscle

- Physio-pedia. (n.d.). Digastric Muscle. Retrieved from https://www.physio-pedia.com/Digastric_Muscle

- Sendić, G. (2023). Digastric: Origin, insertion, innervation and action. Kenhub. Retrieved from https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/digastric-muscle