What is Chromatography?

Chromatography is a powerful laboratory method used to separate, identify, and analyze the components of complex mixtures. Think of it as a molecular race where different substances travel at varying speeds based on their interactions with two key elements: a stationary phase (a solid or liquid-coated surface) and a mobile phase (a liquid or gas that moves through or over the stationary phase). The principle hinges on the fact that each component in a mixture has a unique affinity for these phases. For example, substances that cling tightly to the stationary phase lag behind, while those drawn more to the mobile phase surge ahead. Over time, this creates distinct bands or zones of separation.

The technique comes in many forms, tailored to different needs. Paper chromatography, a classic classroom experiment, uses filter paper as the stationary phase to separate ink dyes. Gas chromatography vaporizes samples to analyze volatile compounds like pollutants or fragrances. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), a sophisticated variant, employs high pressure to achieve rapid, precise separations in pharmaceuticals or biochemistry. Beyond labs, chromatography touches everyday life—testing food safety, diagnosing diseases, or even verifying the authenticity of art by analyzing pigments. Its versatility, precision, and adaptability make it a cornerstone of modern science, quietly shaping fields from forensics to drug development.

What is Column Chromatography?

Column chromatography is a fundamental laboratory technique used to separate and purify individual components from a mixture, leveraging differences in their chemical properties. At its core, the method involves a vertical glass or plastic column packed with a stationary phase—typically a finely divided solid like silica gel or alumina.

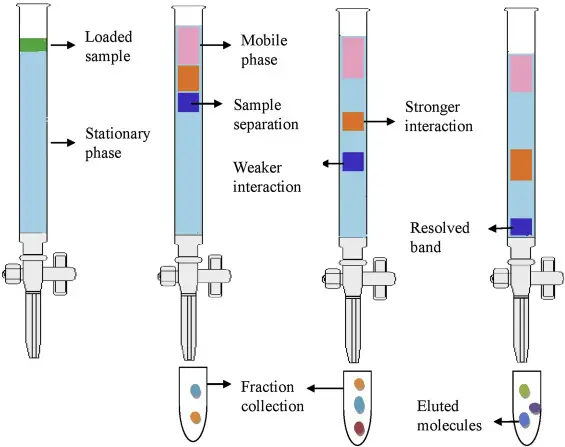

The mixture to be separated is applied to the top of this column, and a solvent or solvent mixture, known as the mobile phase, is gradually passed through it. As the mobile phase flows downward, the components of the mixture interact differently with the stationary phase. Substances that adsorb more strongly to the stationary phase move slower, while those with weaker interactions travel faster, leading to distinct bands of separated compounds.

This principle, akin to thin-layer chromatography (TLC), is scaled up to handle larger quantities, making it ideal for preparative applications such as purifying synthetic compounds or isolating natural products. The process involves careful selection of solvents to optimize separation, and the eluted fractions are collected sequentially as they exit the column.

Variations like normal phase (polar stationary phase) or reverse phase (nonpolar stationary phase) chromatography cater to different compound polarities, while techniques like flash chromatography enhance speed using pressure. Factors such as column size, particle granularity, and solvent flow rate critically influence resolution. By adjusting these parameters, chemists can achieve precise separations, making column chromatography a versatile and indispensable tool in both academic and industrial settings.

Types of Column Chromatography

- Adsorption Column Chromatography – Using a solid stationary phase—such as silica gel or alumina—this method, adsorption column chromatography, separates components according to their differing affinities to the adsorbent surface. Stronger interacting molecules stick more tightly, which slows elution times. Among the uses are natural product isolation and organic compound purification.

- Partition Column Chromatography – Under partition column chromatography, the stationary and mobile phases are liquids. Differential solubility of substances between these two liquid phases allows one to separate them. Mostly used in the separation of polar molecules, this method is crucial in pharmacological and biological studies.

- Ion Exchange Column Chromatography – With a resin-based stationary phase carrying charged functional groups, ion exchange column chromatography helps to separate ions and polar molecules depending on their affinity to the resin. Essential in analytical and preparative chemistry as well as widely utilized in water purification, protein separation, and deionization procedures, it is

- Gel Permeation (Size Exclusion) Chromatography – Gel Permeation with Size Exclusion Chromatography separates molecules depending on size using a porous gel as the stationary phase. Smaller molecules pass the pores and elute later; larger molecules elute faster as they are excluded from the pores. Analyzing polymers and figuring molecular weights especially benefit from it.

- Affinity Column Chromatography – Attaching a particular ligand to the stationary phase, affinity column chromatography—a highly selective technique—binds target molecules with great selectivity. Often used to separate proteins, enzymes, and antibodies, it uses biological interactions to do so.

- Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography – Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography is a method for separating compounds according to their hydrophobic character. Hyphobic groups in the stationary phase interact with non-polar areas of molecules. Purifying proteins without denaturation especially benefits from it.

- Reversed-Phase Chromatography – Reversed-phase chromatography is a variation whereby the mobile phase is polar and the stationary phase is non-polar. Their hydrophobic interactions with the stationary phase help molecules to be arranged. It finds extensive application in the peptide and small chemical molecule separation.

Forms of Column Chromatography

- Gas Chromatography (GC): This technique involves a gaseous mobile phase and a liquid or solid stationary phase. It is primarily used for separating and analyzing volatile compounds. GC is widely applied in environmental analysis, forensic science, and the petrochemical industry.

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): A sophisticated form of column chromatography that utilizes high pressure to push solvents through tightly packed columns containing fine particles. HPLC offers high resolution and speed, making it suitable for complex mixture separations in pharmaceuticals, food safety, and clinical diagnostics.

Principle of Column Chromatography – How does column chromatography work?

- Using a vertical column filled with a stationary phase, such silica gel or alumina, column chromatography is a method for separating components of a mixture depending on their differential interactions.

- The top of the packed column is filled with a mixture (analytes), then the analytes are carried across the stationary phase using a mobile phase (eluent)—either by gravity, pumping, or gas pressure.

- The distribution coefficients of the analytes control the separation by guiding the strength of each compound’s interaction with the stationary phase in relation to its solubility in the mobile phase.

- Whereas those with stronger connections are held longer and elute later, analytes having weaker interactions with the stationary phase travel quicker through the column and elute earlier.

- The type of packing (dry or wet) determines the regularity and efficiency of the separation; the stationary phase can be applied as discrete particles (matrix) or as a thin film on the column wall.

- To maximize the separation of compounds with varying polarities or affinities, the composition of the mobile phase could be fixed (isocratic elution) or altered gradually (gradient elution).

- The separated components, which are gathered in consecutive fractions, elute as the mobile phase passes through the column; thin-layer chromatography or spectroscopy allows one to examine these fractions.

- Factors include column dimensions, particle size of the adsorbent, solvent type, temperature, and applied pressure define the efficiency and resolution of the separation; all of which must be carefully tuned.

- Modern applications, such as automated flash chromatography systems, boost repeatability and throughput by managing solvent flow rates, gradient profiles, and fraction collection.

- Fundamental in both analytical and preparative chemistry for compound purification, metabolite isolation, and compound contamination removal from complicated mixtures, this method is indispensible in research and industrial uses.

- Understanding and maximizing chromatographic separations depend on the differential partitioning of analytes between the mobile and stationary phases, the fundamental process.

Instrumentation of Column Chromatography

Based on their varied interactions with stationary and mobile phases, column chromatography is a flexible method used to separate and purify certain components from complicated mixtures. Column chromatography’s apparatus consists in many important elements:

1. Column: Usually composed of glass or metal, the vertical tube column retains the stationary phase. The size of the separation will affect its dimensions; larger diameters are employed in preparation and smaller ones in analysis. Preventing any reaction with solvents, acids, or bases used during the procedure depends on the column material chosen.

2. Stationary Phase: Usually consisting of solid adsorbents such as silica gel, alumina, or cellulose, the stationary phase is the immobile phase packed within the column. The type of analytes and the intended separation technique—adsorption or partition chromatography—determine the stationary phase to be used.

3. Mobile Phase: The mobile phase—that is, the solvent or mixture containing the analytes—carries them over the column. Its composition is selected depending on its capacity to differently elute the components of the mixture, therefore affecting the separation efficiency.

4. Sample Injection System: The sample introduction can be carried either manually or with automated systems depending on preferred method. Under manual configurations, the sample is gently deposited on top of the column without upsetting the stationary phase. Automated systems can introduce the sample repeatedly using valves and injection loops.

5. Elution Mechanism: Either by gravity, pressure, or pumps, the mobile phase is run through the column either vertically or horizontally. The particular separation needs guide the optimal flow rate and elution technique—isocratic or gradient.

6. Detection System: Depending on the analytes’ characteristics and the needed sensitivity, different detectors—UV-Vis absorbance, refractive index, mass spectrometry—can be used to identify eluted substances.

7. Fraction Collector: A fraction collector can be used to methodically gather these fractions methodically for additional usage or analysis when substances elute from the column at different times.

Steps in Column Chromatography

- Prepare the column by cleaning and drying a suitable glass or metal tube; then, uniformly pack it using the selected stationary phase (using either dry packing, in which the dry adsorbent is added and equilibrated with solvent, or wet packing, in which a slurry is poured into the column) so ensuring no air bubbles are present.

- To stop loss of the stationary phase and preserve even distribution, place a barrier—such as a cotton or glass wool plug—at the bottom of the column.

- Pass the suitable solvent—the first mobile phase—through the packed column to reach a steady state.

- Dissolve the sample in a little mobile phase volume and gently apply it to the top of the column without upsetting the stationary phase.

- Based on the sample complexity, start elution by adding the mobile phase into the column; select either an isocratic technique (using a constant solvent composition) or a gradient elution (gradually altering the solvent polarity).

- Collecting the eluate in sequential fractions helps you to monitor the elution process and guarantee that the flow rate stays constant to guarantee consistent separation.

- Using suitable techniques including spectroscopic detection or thin-layer chromatography (TLC), examine gathered fractions to find which contain the target analyte.

- Combine the fractions including the desired chemical and, if necessary, eliminate the solvent to get the pure substance for next use.

Column Chromatography Experiment – Column Chromatography Procedure

- To guarantee an appropriate glass or stainless-steel column is free from contaminants before use, clean and dry one.

- Either dry packing (adding dry adsorbent followed by solvent equilibration) or wet packing (pouring a slurry of the adsorbent in the mobile phase) load the column uniformly with a chosen stationary phase (e.g., silica gel or alumina) avoiding air bubble development.

- To stop stationary phase loss, cover the bottom of the column with a frit or cotton or glass wool plug.

- Pass a suitable solvent—the initial mobile phase—through the column until a stable, level solvent front is seen and the adsorbent is completely wetened.

- Usually a mixture of chemicals, dissolve the sample in a low volume of the mobile phase to encourage efficient adsorption; next, gently apply this solution to the top of the column.

- Start separating the analytes depending on their different affinities to the stationary phase by adding the mobile phase at a controlled flow rate—using gravity, a pump, or applied gas pressure.

- Sort the eluate in consecutive, well-labeled fractions; the volume of every fraction should be selected depending on the column size and the expected band width of the split compounds.

- Analyzing tiny aliquots from the fractions using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or spectroscopic techniques (e.g., UV-visible absorption) helps one monitor the separation progress and spot the intended component.

- Combine the fractions containing the pure target compound and eliminate the solvent by lyophilization or rotary evaporation, so separating the resultant product.

- To enable repeatability and additional column chromatography process optimization, record all experimental details—including solvent composition, flow rate, fraction quantities, and retention behavior.

Factors Affecting Column Efficiency

In chromatography, column efficiency is the capacity of a column to efficiently separate several components of a mixture thereby generating narrow and clear peaks. Several elements affect this effectiveness:

- Column Packing: Achieving best separation depends on uniform and suitable packing of the stationary phase. Correct column packing reduces voids and channels that could cause unequal flow and lower efficiency.

- Particle Size of the Adsorbent: Reduced particle size of the adsorbent increases the surface area accessible for interactions between the analytes and the stationary phase, hence enhancing separation. Still, extremely tiny particles can cause backpressure and call for careful adjustment.

- Column Dimensions: Column dimension influences resolution by means of its length-to—diameter ratio. Though ratios up to 100:1 can be employed to improve efficiency, depending on the particular application, an ideal ratio is advised as 30:1 or 20:1.

- Mobile Phase Flow Rate: The interaction period between analytes and the stationary phase is determined in part by the mobile phase flow rate. Balance of analysis time and separation quality depends on an ideal flow rate.

- Temperature: Variations in temperature can impact the viscosity of the mobile phase as well as the interactions between analytes and the stationary phase, therefore influencing column efficiency.

Applications of Column Chromatography

- Separation of mixture components for purification

- Isolation of target compounds from crude extracts

- Removal of impurities in chemical synthesis

- Purification of proteins, nucleic acids, and metabolites

- Analysis of drug formulations and quality control

- Isolation of active constituents in natural products

- Preparative-scale separation for industrial applications

Advantages of Column Chromatography

- Can separate a wide variety of mixtures

- Suitable for both small-scale and large-scale separations

- Produces purified compounds for further use

- Offers a wide choice of mobile phases

- Relatively low cost with disposable stationary phases

- Can be easily automated for reproducibility

- Flexible in adjusting sample load and separation conditions

Limitations of Column Chromatography

- Time-consuming process due to slow elution

- Requires large volumes of solvents, increasing cost and waste

- Limited resolution for very similar compounds

- Manual operation can lead to variability

- Potential sample dilution during elution

- Scaling up may be challenging and labor-intensive

FAQ

What is column chromatography?

Column chromatography is a separation technique used to separate and purify components of a mixture based on their differential interactions with a stationary phase and a mobile phase in a column.

What is the principle behind column chromatography?

Column chromatography relies on the differential affinity of components in a mixture for the stationary phase (adsorbent) and the mobile phase (eluent). This leads to their separation as they move through the column at different rates.

What are the different types of column chromatography?

Common types of column chromatography include adsorption chromatography, partition chromatography, ion exchange chromatography, and gel chromatography.

What are the applications of column chromatography?

Column chromatography finds applications in separation, purification, isolation of compounds, analysis of mixtures, estimation of drugs in formulations, and extraction of metabolites from biological fluids.

How does the elution process work in column chromatography?

Elution involves the passage of the mobile phase (eluent) through the column, which causes the separated components to be desorbed from the stationary phase and dissolved in the eluent, resulting in their individual elution from the column.

What factors affect the efficiency of column chromatography?

The efficiency of column chromatography can be influenced by factors such as column dimensions, particle size of the adsorbent, nature of the solvent, temperature, and pressure.

Can column chromatography be automated?

Yes, column chromatography can be automated using advanced systems that control the flow rate, sample injection, and elution process. Automation improves reproducibility and efficiency, but it may add complexity and cost to the technique.

Is column chromatography a time-consuming process?

Yes, column chromatography can be time-consuming, particularly when dealing with complex mixtures or large sample quantities. The separation process can take hours or even days to complete.

What are the limitations of column chromatography?

Limitations of column chromatography include its time-consuming nature, high solvent consumption, complexity and cost of automation, limited separation resolution for closely related compounds, possibility of column overloading, and the lack of a universal method for all compound types.

How can I optimize column chromatography for my specific application?

To optimize column chromatography, consider factors such as the choice of stationary phase, mobile phase composition, flow rate, column dimensions, and sample loading. Optimization may require experimentation, method development, and expertise in chromatographic techniques.

References

- Wilson, K., Walker, J. (2018). Principles and Techniques of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (8 eds.). Cambridge University Press: New York.

- https://www.slideshare.net/shaisejacob/column-chromato

- https://www.slideshare.net/RameshJupudi/column-chromatography-ppt

- https://chromatography.conferenceseries.com/events-list/applications-of-chromatography

- https://www.slideshare.net/krakeshguptha/column-chromatography-26966949

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/medical/column%20chromatography

- http://library.umac.mo/ebooks/b28050630.pdf