Protochordate larvae is the juvenile stage found in lower chordates, and it is seen in members of Urochordata and Cephalochordata. It is the stage where the animal shows the typical chordate features very clearly. It is the notochord, dorsal hollow nerve cord, pharyngeal slits, and the post-anal tail that appear in this larval period.

It is these characters which indicate their relationship with chordates. The notochord is a rod-like supporting structure that appears along the dorsal side of the body. It is rigid and flexible, and it provides support to the larva and acts as an early form of the vertebral column.

The dorsal hollow nerve cord lies above the notochord and acts as the main conducting pathway for nerve impulses. The pharyngeal slits appear in the throat region and help in filter feeding or respiration depending on the species. The post-anal tail extends beyond the anus and it helps the larvae in movement and balance in water.

It is the larval stage of Urochordates that is highly specialized, and it has a well-developed tail, notochord, sensory vesicle, ocellus and otolith which help the larva in swimming and locating substratum. This larva is active but mostly non-feeding, and later it undergoes retrogressive metamorphosis in which the advanced chordate features disappear and the adult becomes sedentary. In Cephalochordates, the larva is planktonic and feeding. It has a notochord that extends up to the anterior region and it shows left-right asymmetry of the body. This larva develops progressively into the adult form.

Protochordate larvae are important because they show the basic chordate plan in a very clear manner. It is this stage which helps in understanding the evolution, origin, and affinities of chordates.

Larval forms of Protochordata

Protochordates include Urochordata and Cephalochordata. It is the group which shows the early chordate body plan in larval stages. The larval forms are important because these show the basic chordate characters like notochord, dorsal hollow nerve cord, pharyngeal gill slits and post-anal tail. It is the stage where many features is present temporarily or permanently depending on the group.

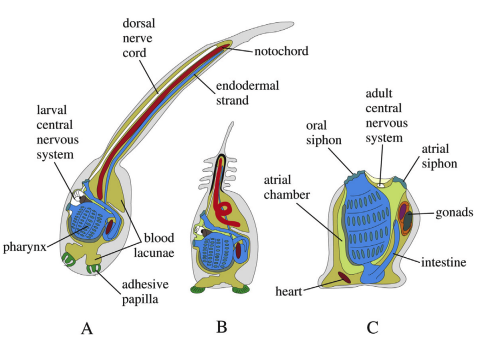

I. Urochordata Larva (Ascidian Tadpole Larva)

The ascidian larva is called tadpole larva. It is free-swimming and active. It is the stage used for dispersal. It is the process where the larva swims for a short time and then attaches to a substratum.

The larva is non-feeding (lecithotrophic) because yolk reserves is used and the gut is not fully developed. After settlement, retrogressive metamorphosis occurs. This is referred to as the process where advanced chordate characters is lost and the adult becomes sessile.

Chordate Features (Temporary)

Some of the main features are–

- Notochord is present only in the tail region and it extends from the posterior wall to the tip. It disappears in adult.

- The nervous system is a dorsal hollow nerve cord which is enlarged in front forming cerebral vesicle. Later it is reduced to a single ganglion in adult.

- The tail has a caudal fin used in swimming and balance.

- Sensory vesicle has statocyst and ocelli.

Other Structures

Three adhesive papillae is present in the anterior region. These help in attachment.

Pharynx has endostyle and a single pair of gill slits which open into atrium. These are retained in adult.

II. Cephalochordata Larva (Amphioxus Larva)

The larva of Branchiostoma is planktonic and feeding type. It is the process where continuous feeding and growth occurs for weeks or months. Development is progressive and no retrogressive change is found. After development, the larva settles and becomes a burrowing filter feeder.

Chordate Features (Permanent)

These are–

- Notochord persists throughout life and extends forward into the rostrum.

- The body is elongated, transparent, laterally compressed and fish-like.

- The anterior end has oral hood with many oral cirri which help in food capture. Pharynx is perforated by gill slits.

Larval Asymmetry

- This larva shows strong left-right asymmetry.

- In this step, the mouth and preoral pit open on the left side.

- Endostyle and club-shaped gland are present on the right side.

- The first gill slit opens on the right.

- Among the important features, somites show asymmetrical arrangement where left somites are shifted slightly forward. During metamorphosis this asymmetry becomes reduced.

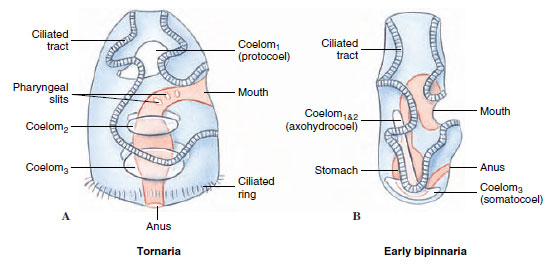

III. Tornaria Larva (Contextual, Hemichordata)

Tornaria larva is mentioned because it resembles echinoderm larva. It is transparent, free-swimming and has ciliary bands. It is the dipleurula-type larva. This larva lacks notochord and dorsal nerve cord. It shows that hemichordates is more related to echinoderms.

Characteristics of Protochordate Larvae

General Characteristics of Protochordate Larvae

- It is the stage where the basic chordate features is present.

- The body is bilaterally symmetrical and triploblastic.

- A notochord is present which act as supporting rod.

- The dorsal hollow nerve cord is seen in the larval body.

- Pharyngeal gill slits is present for filter feeding or respiration.

- Endostyle is present in the pharyngeal floor.

- A post-anal tail is developed for locomotion.

- These larvae is marine in habitat.

Characteristics of Urochordate Larvae (Ascidian Tadpole)

- The larva is free-swimming and active in water.

- It is non-feeding type and depends on yolk reserve.

- Notochord is restricted only in the tail region.

- A long tail with fin is present for swimming.

- The dorsal hollow nerve cord extends into a cerebral vesicle.

- Sensory organs like ocellus and otolith is present in the cerebral vesicle.

- Three adhesive papillae is present in the anterior region for attachment.

- Retrogressive metamorphosis is seen where tail, notochord and nerve cord is lost.

Characteristics of Cephalochordate Larvae (Amphioxus Larva)

- It is planktonic and filter-feeding throughout the larval period.

- Development is progressive and the larval body gradually transform into adult.

- Notochord extends anteriorly beyond the nerve cord.

- An oral hood with oral cirri is present for feeding.

- Left-right asymmetry is present during larval stage.

- The mouth and pre-oral pit open on left side.

- The first gill slit appears on the right side.

- The somites show alternating pattern on both sides.

- Larva is slender, transparent and laterally compressed with pointed rostrum.

1. Tornaria larva of Balanoglossus ( Hemichordates)

- It is the larval form of Balanoglossus and it was first described by J. Müller, later it was identified correctly by Metchnikoff who named it Tornaria due to its circular rotating movement.

- The body is transparent and elongated. It has a distinct anterior and posterior region which is clearly visible in larval stage.

- At the anterior side the prototroch is present which acts in movement and feeding. At the posterior side the telotroch is present. These are ciliary bands helping in swimming.

- It is the process in which the larva shows circular rotation behaviour. The rotation help in feeding and free swimming in water.

- This larva is important because it helped in identifying the life cycle of Balanoglossus. It is referred to as the larval connection between adult and early developmental stage.

- Tornaria is the planktonic larval stage. These larvae occur freely in water until metamorphosis take place when adult Balanoglossus is formed from eggs laid by adults.

- The ecological role is that Tornaria larvae help in dispersion of population and feeding in planktonic conditions which allow a broader distribution of hemichordates.

- It indicates that Tornaria larva is well recognised as the larval stage of Balanoglossus and its characteristic features explain the development and classification pattern of hemichordates.

Structure of Balanoglossus

Some of the main structural features are–

- The body of Balanoglossus is soft and worm-like. It is divided into three main regions which is the typical plan of hemichordates.

- The anterior part is the proboscis. It is muscular and helps in burrowing. Inside it the stomochord is present which is an outgrowth from pharynx.

- Behind the proboscis the collar region is present. It is small and circular. The nerve cords is meeting in this region forming a tube-like structure.

- The trunk is the longest region. It contains pharynx with gill-slits, oesophagus, stomach and intestine. The gonads is arranged in rows on the trunk. The anus is present at the posterior end.

- The body wall has epidermis with cilia. Below the epidermis the muscle layer is present which help in movement inside the burrow.

- Coelomic compartments are present in proboscis, collar and trunk. These coeloms are separated and helps in body support.

- The circulatory system is simple. It is the process where a dorsal vessel and ventral vessel is present and the heart-vesicle is located in the proboscis region.

- The respiratory part is the gill-slits in the pharynx. These slits is helping in water flow and gaseous exchange.

- The alimentary canal is straight and runs from mouth to anus. Mouth opens at the base of the proboscis and leads into pharynx.

- The nervous system is mainly in the form of dorsal and ventral nerve cords. These cords show collar region specialisation.

Reproduction of Balanoglossus

- Balanoglossus shows sexual reproduction and the sexes is separate. The gonads occur in longitudinal rows on the trunk region.

- The gonads arise from the coelomic wall and inside it the germinal epithelium produce sperms and eggs. It is the process where gametogenesis take place through cell division and maturation.

- Mature gametes are released to outside through genital pores. This release is important because fertilization occur in seawater.

- Fertilization is external. The sperms and eggs meet in surrounding water and form the zygote.

- After fertilization two types of development is present. In indirect development the tornaria larva is formed. It is free-swimming and has cilia for movement and feeding.

- In this larval type the protocoel is formed which later produce the proboscis coelom. The collar and trunk parts develop by invagination of hind gut.

- The tornaria metamorphoses and settles at the bottom. It is then changed into adult Balanoglossus.

- In direct development some species do not form larva. The embryo grow inside a larger egg and form a small adult-like juvenile.

- Direct development avoid a free-swimming stage and the young one resemble the adult structure from beginning.

Development of Balanoglossus

Balanoglossus shows two fundamental developmental pathways—indirect development through a distinct tornaria larva, and direct development where the larval stage is absent.

Many indirect-developing species, such as Balanoglossus simodensis, possess the full set of twelve Ambulacrarian-type Hox genes, which underlie the timing and patterning of larval vs adult regions.

I. Indirect Development (Via Tornaria Larva)

A. Fertilization and Early Embryogenesis

- Sexes are separate although the species is often casually described as hermaphrodite in older descriptions; gonads are arranged in longitudinal rows along the alimentary canal.

- Gonads arise from the coelomic wall, and germinal epithelium inside them produces sperms and eggs by gametogenesis.

- Mature gametes get released outside through a genital pore, where fertilization is strictly external.

B. Tornaria Larva (The “Head Larva”)

- The tornaria represents the characteristic planktonic larval stage—transparent, oval, and freely swimming in the surface waters.

- J. Müller (1805) first mistook it for an echinoderm larva due to its striking similarity to bipinnaria; Metchnikoff (1869) later identified it correctly and introduced the term “Tornaria,” mainly because of its circular rotating movement.

- Locomotion is mediated by continuous ciliary bands—an anterior prototroch and a posterior telotroch—that support swimming, feeding, and basic respiration.

- The larva carries an apical plate with a tuft of cilia and paired eyespots, forming a sensory region that guides movement.

- A complete digestive canal is present from mouth to anus; the larva is capable of filter-feeding and active growth. The mouth lies ventrally; the anus is positioned near the blastoporal region.

C. Head-Larva Concept and Hox-Gene Patterning

- Developmental data indicate that tornaria primarily represents an expanded anterior domain, often referred to as a “head territory.”

- Early larval growth largely involves anterior tissues, whereas trunk-forming Hox genes activate later, typically closer to metamorphosis.

- Such delayed trunk patterning resembles other bilaterian feeding larvae, collectively termed “head larvae,” where anterior expansion precedes posterior differentiation.

D. Metamorphosis and Adult-Body Formation

- Metamorphosis begins with the organization of the protocoel, which becomes the proboscis coelom in the adult.

- A proboscis pore develops early, followed by the sequential differentiation of collar and trunk regions arising from hind-gut invagination.

- The alimentary canal differentiates into esophagus, stomach, and intestine.

- After completing larval feeding and growth, the tornaria settles on the substrate and transforms into the segmented adult with its distinct tripartite body plan—proboscis, collar, and trunk.

III. Direct Development

- Some Balanoglossus species avoid the tornaria stage entirely and form juveniles directly.

- Direct development typically occurs in species producing larger, yolk-rich eggs.

- The embryo gradually remodels into a miniature adult without a free-swimming larval phase.

IV. Evolutionary Context (Dorso–Ventral Axis and Ancestral Patterns)

- Hemichordate development is central for tracing the evolutionary origin of the chordate body plan, especially the inversion of the dorso–ventral axis.

- In hemichordates and echinoderms, BMP signaling dominates the aboral side, while chordin is expressed on the oral side—this pattern contrasts with cephalochordates where BMP is ventral and chordin is dorsal.

- The evolutionary inversion in chordates may relate to modifications in BMP–chordin signaling inherited from an indirect-developing ancestor.

- Mouth formation also differs: hemichordates form the mouth on the non-BMP side.

- Ancestral deuterostomes are proposed to have been benthic, worm-like organisms with terminal mouth and anus, and the earliest chordate ancestor likely resembled a free-living acorn-worm type body plan.

2. Ascidian tadpole larva of Urochordata

- The ascidian tadpole larva is the free-swimming larval stage of urochordates like Ascidia and Herdmania. It is important because it shows the chordate characters which are lost in adult.

- The larva has notochord in the post-anal tail. It is the structure giving support and helping in swimming.

- A dorsal hollow nerve cord is present. In the anterior part it enlarge to form the sensory vesicle which works like a simple brain.

- A long post-anal tail is present with muscles and fin folds. This tail act as the locomotory organ.

- Pharyngeal gill-slits are present in the trunk. These slits with the endostyle (present on floor of pharynx) indicate its chordate nature.

- The sensory vesicle has an ocellus for light response and an otolith which act as balance organ. These help the larva in orientation during swimming.

- The larva is usually non-feeding. It uses yolk for survival and swim actively to find a suitable substratum.

- At the anterior end three adhesive papillae is present. These papillae help in attachment when the larva settle.

- After attachment the larva undergo retrogressive metamorphosis. It is the process where tail, notochord, nerve cord, ocellus and otolith disappear and the animal change into a sessile adult.

- The adult retain only simple structures for filter feeding but the larval form clearly show its chordate position.

In: Minelli, A., Contrafatto, G. (Eds.), Biological Science Fundamentals and Systematics. Oxford: Eolss Publishers. Available at: http://www.eolss.net.

Structure of Urochordata Larva

I. Overall Morphology and Integument

- The larva shows a classic tadpole-like body plan with a short oval trunk and an elongated post-anal tail; the entire body is clearly bilaterally symmetrical.

- It is an active, free-swimming dispersal stage; propulsion depends almost entirely on the muscular tail.

- A continuous caudal fin, merging with slender dorsal and ventral fin folds, assists in stabilization and forward thrust; faint striations are visible along the fin.

- The outer covering is a thin tunic (test) secreted by ectodermal cells, giving protection while still allowing flexibility.

II. Chordate Synapomorphies (Temporary, Larva-Specific)

- Notochord runs only in the tail region—from the posterior trunk wall to the tip—giving rigidity and acting as an axial support. The name Urochordata refers to this tail-restricted notochord.

- Dorsal Hollow Nerve Cord (DHNC) extends along the dorsal tail and enlarges anteriorly into the sensory (cerebral) vesicle in the trunk.

- Post-anal Tail is muscular and elongated, protruding behind the anus; it provides the main locomotory force during the larva’s short active phase.

III. Central Nervous System and Sensory Organs

- The sensory vesicle (brain) lies in the anterior trunk and houses most neural and sensory processing cells. In Ciona intestinalis, the CNS consists of ~335 cells, with ~215 concentrated in this vesicle.

- The ocellus (photoreceptor) detects light intensity and direction. It includes:

- A cup-shaped pigmented supportive cell.

- Around 15–20 sensory cells (or a dozen pigmented retinal-type cells).

- Three small lens cells.

- The photopigment used is Ci-opsin1, a vertebrate-type opsin homolog.

- The otolith (statocyst) is a single pigmented gravity receptor cell that helps the larva orient itself relative to gravity.

IV. Visceral and Attachment Structures

- Digestive system is present but poorly functional; the larva is lecithotrophic, and the post-pharyngeal gut is rudimentary.

- Pharynx already bears a functional endostyle on its ventral side—this secretes mucus for filter-feeding and is evolutionarily homologous to the vertebrate thyroid gland.

- Gill slits (one pair) open into an atrial cavity; these structures support early respiratory exchange.

- Atrial cavity and opening lie dorsally around the throat region, acting as a chamber for water flow.

- Circulatory elements, including a small heart and pericardium, are present within the trunk.

- Attachment organs include three adhesive papillae situated at the anterior end; these ectodermal papillae enable settlement and permanent attachment during metamorphosis.

- Tail musculature consists of three mesoderm-derived muscle cell rows on either side of the notochord, enabling rapid tail beating.

Development of Urochordata Larva

I. Embryogenesis and Larval Formation

- Early development starts with cleavage producing a blastula; gastrulation forms ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm. Ascidians follow a highly deterministic (mosaic) developmental program where ooplasmic segregation fixes the fate of many cells from the very start.

- Mosaic cytoplasmic regions predefine future tissues—tail muscles, the tail notochord, neural plate, and pigment-cell precursors—leading to a rapid, highly specialized tadpole larva.

- As the larva forms, a distinct trunk and a long post-anal tail appear. The notochord remains confined strictly to the tail.

- The dorsal hollow nerve cord forms via neurulation and extends into the tail; the anterior neural region enlarges into the sensory (cerebral) vesicle.

- Sensory vesicle development yields two major sensory organs: the ocellus (light detector) and the otolith (statocyst).

- Pigment-cell precursors arise as bilateral equivalence groups, completing initial determination by mid-gastrula.

- These precursor cells migrate medially after neurulation.

- BMP–Chordin interactions regulate their fate; in most species the ocellus pathway dominates, while the secondary precursor differentiates into the otolith by default.

II. Free-Swimming Phase and Settlement

- The freshly hatched larva is active, fast-moving, and free-swimming; its life span is short (often only a few hours). It is strictly lecithotrophic, relying on yolk; its gut is functionally minimal.

- The primary ecological role of the tadpole is dispersal. Initially, it shows positive phototaxis and negative geotaxis—swimming upward and toward light to remain in the open water.

- As settlement approaches, behavior reverses: the larva becomes sluggish, switches to negative phototaxis and positive geotaxis, and moves downward toward the substrate.

- Attachment occurs through three adhesive papillae on the anterior trunk. Once anchored, the larva adopts an inverted posture, and metamorphic changes begin immediately.

III. Retrogressive Metamorphosis

Retrogressive metamorphosis transforms an advanced, chordate-featured larva into a simplified, sessile adult.

- Degenerative changes:

- The long tail reduces rapidly and vanishes along with its fin.

- Notochord cells, tail muscles, and the dorsal nerve cord disintegrate and are engulfed by phagocytes.

- The elaborate larval sensory organs (ocellus and otolith) disappear completely.

- Adhesive papillae degenerate after their function is fulfilled.

- In molgulid ascidians, the ocellus precursor and extra pigment cells undergo programmed cell death (PCD), as indicated by SYTOX-stained apoptotic nuclei.

- Progressive changes toward the adult form:

- The pharynx expands markedly; gill slits multiply by subdivision.

- The atrial cavity enlarges into a broad water chamber supporting filter-feeding.

- The post-pharyngeal gut elongates and differentiates into adult digestive regions.

- Gonads and associated ducts arise from mesodermal components.

- Rapid growth between the point of attachment and the mouth causes the mouth to rotate ~90°, reaching its adult orientation.

Final Outcome

The transformation results in a sessile, filter-feeding adult lacking notochord, tail musculature, dorsal nerve cord, and larval sense organs.

Only the endostyle and pharyngeal gill slits remain as retained chordate features—reflecting a striking shift from a highly motile chordate larva to a fixed, simplified tunicate adult.

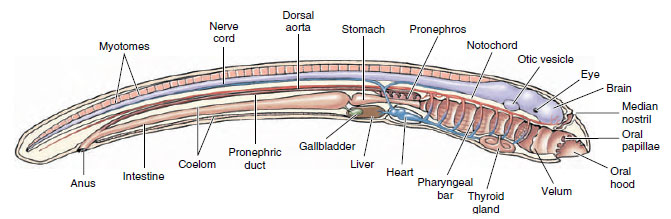

3. Larval tunicates of Lancet (Cephalochordates)

- The term refers to the larval stage of cephalochordates, which is known as the amphioxus larva. Cephalochordates are also called lancelets.

- The larva is transparent and laterally compressed. It is long and pointed at both ends and looks like a small fish.

- It is planktonic and filter-feeding. The larva remain in water column for long period and feed on small plankton using oral structures.

- The notochord extend forward beyond the nerve cord. This notochord is present from head to tail and remain throughout life.

- An oral hood is present at the anterior end. It has many oral cirri that act in filtering and preventing large particles from entering.

- The pharynx has gill-slits. These slits help in filter feeding and lead to the atrium which later opens through atriopore.

- A dorsal hollow nerve cord run along the body. It control movement and other responses.

- The larva shows left–right asymmetry. The mouth and preoral pit occur on the left side. The somites also show a shifted arrangement between left and right side.

- Development is progressive. The larva gradually enlarge and form the adult benthic lancelet without losing chordate characters.

- This larva is considered closer to ancestral chordate condition because it retain full axial pattern and complex feeding behaviour.

Structure of Cephalochordata Larva

I. General Morphology and Chordate Features

- The larval amphioxus is slim, transparent, and laterally compressed, with both ends tapering into sharp points—hence the term amphioxus (“pointed at both ends”).

- The body is elongated and propelled by a mid-dorsal fin that runs along much of its length; swimming stability is supported by a narrow post-anal tail.

- The notochord is a continuous axial rod extending all the way to the anterior tip, even beyond the cerebral vesicle—this forward extension is the major reason the group is known as Cephalochordata (“notochord in the head”).

- A hollow dorsal nerve cord lies just above the notochord; its anterior region forms a small cerebral vesicle without forming a tripartite vertebrate-like brain.

- This dorsal neural tube acts as the central signaling pathway and maintains the core chordate organization throughout the larval and adult stages.

II. Feeding Apparatus and Filter-Feeding Structures

- A pointed rostrum extends at the anterior end; just below it lies the oral hood, lined with 20 or more oral cirri that help sieve plankton and exclude larger particles.

- The oral hood opens into a buccal cavity (vestibule) which funnels water toward the pharyngeal basket.

- The pharynx bears numerous pharyngeal slits used both for feeding and respiration. During development, these slits eventually communicate with an atrium that encloses the pharynx laterally.

- A ventral digestive gut extends posteriorly for nutrient absorption.

- Excretion is primitive and occurs through protonephridial solenocytes, which remove metabolic waste from the coelomic fluid.

III. Left–Right Asymmetry (Distinctive Larval Trait)

- Cephalochordate larvae show strong left–right structural asymmetry, affecting ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal derivatives—an uncommon but defining feature.

- Somite patterning is asymmetric: left somites sit half a segment ahead of their right-side counterparts, a pattern sometimes compared to “gliding symmetry” in early metazoans.

- Pharyngeal region asymmetry:

- The mouth and preoral pit form exclusively on the left side of the larva.

- Structures such as the endostyle and club-shaped gland show pronounced sidedness regulated by Nodal signaling; when Nodal is inhibited, some lose their normal left-biased identity and appear bilaterally or ectopically.

- Anus positioning shifts developmentally—starting from a right-sided position, moving to mid-ventral, and finally shifting left in later larval stages.

- This entire asymmetrical architecture depends on the conserved Nodal-Pitx signaling pathway, and may involve a cilia-based Left–Right Organizer (LRO) generating leftward flow, similar to vertebrates.

- The rapid establishment of sidedness is thought to support the early efficiency of the feeding system, which is essential for the larva’s planktonic lifestyle.

Development of Cephalochordata Larva

I. Early Embryogenesis and Larval Life History

- Fertilization is external; gametes are released into seawater, usually around sunset during warm seasons. Spawning and early cleavage resemble other deuterostomes, especially sea urchins, with holoblastic segmentation.

- Embryogenesis progresses through ten defined developmental periods shared across different amphioxus species, reflecting a conserved ancestral pattern.

- The free-swimming larva is planktonic and long-lived, remaining in the water column for weeks or even months—this long larval span ensures wide dispersal potential.

- Newly hatched larvae swim using cilia, but later locomotion shifts to muscular twitching of the elongated tail.

- Larvae are active filter–feeders, ingesting phyto- and zooplankton, unlike the lecithotrophic larvae of ascidians.

II. Chordate Structure Formation

- Notochord development- The larval notochord forms by pouching-off from the dorsal archenteron during neurulation. Except for the most anterior tip, its cells are individualized from somites. Posterior proliferation is required to extend the full notochord length, a trait shared with vertebrates and thought to reflect ancestral chordate conditions.

- Nervous system- The neural plate rounds up beneath the dorsal ectoderm and later detaches to become a closed neural tube. An anterior vesicle forms, but does not regionalize into a vertebrate-like brain.

- Somites and segmentation- Somites arise bilaterally in an anterior-to-posterior sequence. Early somites form by enterocoely, while later ones arise via schizocoely (an unusual combination among deuterostomes). These somites mature into V-shaped myomeres for later locomotion.

III. Left–Right Asymmetry and Organogenesis

Amphioxus larvae display a characteristic, marked left–right asymmetry across tissues from all germ layers.

- Somite asymmetry- The left somite row lies half a segment ahead of the right side—a classic example of glide-reflection symmetry.

- Pharyngeal asymmetry– The larval mouth and preoral pit arise exclusively on the left side, giving the larva a distinct lateralized feeding apparatus.

- Anus migration– The anus begins on the right, moves to the mid-ventral line, and later shifts to the left in more advanced larvae.

- Endostyle-associated structures– The club-shaped gland and endostyle components develop on the side opposite the mouth—typically on the right.

- Nodal signaling mechanism–

- Left-sided identity is set during early neurula stages (N0–N2) through the conserved Nodal pathway.

- Inhibition of Nodal signaling causes loss of left-sided features (no mouth, no preoral pit) and duplication of right-sided identities (ectopic endostyle, club-shaped gland on left side).

- L–R asymmetry may originate from a ciliated Left–Right Organizer (LRO), generating leftward fluid flow much like vertebrate embryos.

- The LRO is positioned near developing somites and the emerging pharynx, allowing rapid and direct influence on feeding organs that must become functional within one to two days.

IV. Metamorphosis (Progressive Development Toward the Adult)

Amphioxus metamorphosis is progressive, maintaining and elaborating chordate features rather than reducing them (contrast with retrogressive tunicate metamorphosis).

- Structural transitions-

- Larval ectodermal cilia disappear.

- The club-shaped gland degenerates.

- The mouth shifts from a left–lateral position to an antero-ventral location.

- Epidermal folds develop an oral hood, and oral cirri plus ciliated wheel organs appear to support adult filter-feeding.

- Gill slits subdivide, enlarging respiratory and filter-feeding surfaces.

- Adult body plan –

- The notochord remains fully extended head-to-tail.

- Segmented axial musculature (myomeres) persists and drives adult swimming.

- The body becomes partly symmetric again, though myomeric asymmetries remain embedded from larval history.

FAQ

1. What are the larval forms in protochordates?

Answer: Protochordates exhibit several larval forms such as the ascidian tadpole larva (Urochordata), the amphioxus larva (Cephalochordata), and the tornaria larva found in Hemichordates (Balanoglossus). These larvae represent early chordate body plans and show essential chordate features.

2. What is the significance of studying larval forms in protochordates?

Answer: Larval forms are significant because they reveal primitive chordate characteristics, provide clues about ancestral developmental patterns, and help understand evolutionary relationships between hemichordates, urochordates, cephalochordates, and vertebrates. They also give insight into the origin of chordate organs, axis formation, and body-plan evolution.

3. What are the essential chordate characters exhibited by protochordate larvae?

Answer: Protochordate larvae show the four fundamental chordate traits:

- Notochord

- Dorsal hollow nerve cord

- Pharyngeal gill slits

- Post-anal tail

- They may also possess an endostyle, another key chordate organ.

4. What are the four types of larval forms of protochordates?

Answer: The four commonly described larval forms are:

- Ascidian tadpole larva (in Urochordata)

- Amphioxus larva (in Cephalochordata)

- Tornaria larva (in Hemichordata)

- Planula-like early chordate larva (theoretical ancestral form used in evolutionary discussions)

5. What is an ascidian tadpole larva?

Answer: The ascidian tadpole larva is the free-swimming, chordate-like larval stage of tunicates (Urochordata). It possesses a complete set of chordate characters but exists only briefly before settling and undergoing retrogressive metamorphosis.

6. What are the characteristics of the ascidian tadpole larva?

Answer:

- Slender trunk with a long post-anal tail

- Tail contains a notochord and dorsal nerve cord

- Possesses ocellus (light receptor) and otolith (statocyst)

- Three adhesive papillae at the anterior end

- Non-feeding, short-lived, and actively swimming

- Shows all chordate characters temporarily

7. What is a tornaria larva?

Answer: The tornaria larva is the planktonic, ciliated larval stage of Hemichordates (e.g., Balanoglossus). It resembles echinoderm larvae (bipinnaria), reflecting the evolutionary closeness between hemichordates and echinoderms.

8. What are the general characteristics of tornaria larva?

Answer:

- Transparent, oval body with prototroch and telotroch ciliary bands

- Free-swimming and planktonic

- Possesses an apical plate, eyespot, and a complete digestive tract

- Shows circular, rotating swimming motion

- Exhibits left–right symmetry and ciliary locomotion

- Represents the indirect development pathway of hemichordate

9. What is retrogressive metamorphosis in Urochordates?

Answer: Retrogressive metamorphosis is the process in which the advanced chordate larval features (notochord, dorsal nerve cord, tail, sense organs) degenerate, and the organism transforms into a simple, sessile adult tunicate. The adult becomes a filter-feeder with only pharyngeal slits and an endostyle retained.

10. How does metamorphosis occur in Ascidia?

Answer:

- The larva swims, settles using adhesive papillae, and attaches to a substrate

- Tail, notochord, and nerve cord degenerate

- Sense organs disappear

- The body rotates ~90°, mouth shifts to the adult position

- Pharynx enlarges and gill slits multiply

- The adult becomes sessile and filter-feeding

11. What is the role of the notochord in protochordate larvae?

Answer: The larval notochord provides rigidity, support, and swimming efficiency. It acts as a central structural axis, allowing muscular contractions to create coordinated tail movements for locomotion.

12. What is the Echinoderm theory of the origin of chordates?

Answer: The Echinoderm theory proposes that chordates evolved from echinoderm-like ancestors. Similarities between tornaria and echinoderm larvae suggest a common deuterostome ancestor, and inversion of the dorso–ventral axis may have given rise to the chordate body plan.

13. What is Garstang’s hypothesis regarding the origin of vertebrates?

Answer: Garstang suggested that vertebrates originated through paedomorphosis (neoteny) of an ascidian tadpole larva. He proposed that the larva retained its chordate features into adulthood instead of undergoing retrogressive metamorphosis—leading to the first vertebrate-like ancestor.

14. How do protochordates differ from vertebrates?

Answer:

- Protochordates lack a vertebral column, cranium, and advanced brain

- Their circulatory, nervous, and sensory systems are simpler

- They exhibit larval chordate features but retain fewer in adults

- Reproduction and locomotion are primitive

- Vertebrates show cephalization, segmentation, and complex organ systems

15. What is the concept of Protochordata?

Answer: Protochordata is a non-taxonomic grouping that includes Hemichordata, Urochordata, and Cephalochordata. They represent primitive forms showing basic chordate features, bridging the evolutionary gap between invertebrates and vertebrates.

- Bertrand, S., & Escriva, H. (2011). Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: amphioxus. Development, 138(22), 4819–4830. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.066720

- BYJU’S. (n.d.). Characteristics of Protochordata. Retrieved from https://byjus.com/biology/protochordata/

- D’Aniello, S., Bertrand, S., & Escriva, H. (2023). The Natural History of Model Organisms: Amphioxus as a model to study the evolution of development in chordates. eLife, 12, e87028. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.87028

- Duboc, V., & Lepage, T. (2008). A conserved role for the nodal signaling pathway in the establishment of dorso-ventral and left-right axes in deuterostomes. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution, 310(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.b.21121

- Duboc, V., Rottinger, E., Lapraz, F., Besnardeau, L., & Lepage, T. (2005). Left-right asymmetry in the sea urchin embryo is regulated by nodal signaling on the right side. Developmental Cell, 9(1), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.008

- Holland, L. Z. (2015). The origin and evolution of chordate nervous systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1684), 20150048. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0048

- Holland, L. Z., Albalat, R., Blow, M. J., Bronner-Fraser, M., Brunet, F., Butts, T., Candiani, S., et al. (2008). The amphioxus genome illuminates vertebrate origins and cephalochordate biology. Genome Research, 18(7), 1100–1111. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.073676.107

- Holland, L. Z., & Li, G. (2021). Laboratory culture and mutagenesis of Amphioxus (Branchiostoma Floridae). In D. J. Carroll & S. A. Stricker (Eds.), Developmental Biology of the Sea Urchin and Other Marine Invertebrates: Methods and Protocols (pp. 1–29). Humana Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0974-3

- Holland, P. W., Holland, L. Z., Williams, N. A., & Holland, N. D. (1992). An amphioxus homeobox gene: Sequence conservation, spatial expression during development and insights into vertebrate evolution. Development, 116(3), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.116.3.653

- Huang, Z., Xu, L., Cai, C., Zhou, Y., Liu, J., Xu, Z., Zhu, Z., Kang, W., Cen, W., Pei, S., et al. (2023). Three amphioxus reference genomes reveal gene and chromosome evolution of chordates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(17), e2201504120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2201504120

- Jeffery, W. R. (1997). Evolution of ascidian development: Interspecific modifications of the tadpole larva have revealed some of the mechanisms of evolutionary change in development. BioScience, 47(7), 417–425. https://doi.org/10.2307/1313057

- Kusakabe, T., Kusakabe, R., Kawakami, I., Satou, Y., Satoh, N., & Tsuda, M. (2001). Ci-opsin1, a vertebrate-type opsin gene, expressed in the larval ocellus of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. FEBS Letters, 506(1), 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02877-0

- Lacalli, T. C. (2005). Protochordate body plan and the evolutionary role of larvae: Old controversies resolved? Canadian Journal of Zoology, 83(1), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1139/z04-162

- Poss, S. G., & Boschung, H. T. (1996). Lancelets (Cephalochordata: Branchiostomatidae): How many species are valid. Israel Journal of Zoology, 42(Supplement 1), S13–S66.

- Putnam, N. H., Butts, T., Ferrier, D. E. K., Furlong, R. F., Hellsten, U., Kawashima, T., Robinson-Rechavi, M., et al. (2008). The amphioxus genome and the evolution of the chordate karyotype. Nature, 453(7198), 1064–1071. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06967

- Sadiya College. (n.d.). Retrogressive metamorphosis in Urochordates. [Unpublished manuscript or lecture notes].

- Sato, S., & Yamamoto, H. (2001). Development of pigment cells in the brain of ascidian tadpole larvae: Insights into the origins of vertebrate pigment cells. Pigment Cell Research, 14(6), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0749.2001.140602.x

- Satoh, N., Rokhsar, D., & Nishikawa, T. (2014). Chordate evolution and the three-phylum system. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1794), 20141729. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1729

- Soukup, V. (2017). Left-right asymmetry specification in amphioxus: Review and prospects. The International Journal of Developmental Biology, 61(10–11–12), 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1387/ijdb.170251vs

- Soukup, V., Yong, L. W., Kozmik, Z., & Yu, J.-K. (2015). The Nodal signaling pathway controls left-right asymmetric development in amphioxus. EvoDevo, 6(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-9139-6-5

- Su, L., Shi, C., Huang, X., Wang, Y., & Li, G. (2020). Application of CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease in Amphioxus genome editing. Genes, 11(11), 1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11111311