Ribozymes are catalytic RNA molecules, and it is the process where RNA itself act as an enzyme in different biochemical reactions. It is the first biological evidence that RNA can work both as a genetic material and also as a catalyst. This is referred to as the dual activity of RNA, and it gives support to the RNA world hypothesis that early life might be dependent on RNA before the appearance of DNA and proteins.

It is the folded structure of RNA that helps in forming the active site where the reaction is catalyzed. These are mostly involved in phosphoryl transfer reactions, and the reaction is carried out when the 2′-hydroxyl group is activated to attack the adjacent phosphate group. The cleavage or ligation of RNA strands is then completed, and this mechanism is controlled by general acid-base catalysis. The major source of catalytic activity comes from nucleobases or hydrated metal ions that are present within the ribozyme structure.

Some of the important naturally occurring ribozymes are hammerhead, hairpin, HDV, and twister types which are present in plant viruses and also in some mammalian mRNA. These ribozymes is involved in self-cleaving steps during replication or regulation of gene expression. Among the important examples, the ribosome is considered a ribozyme because its peptidyl transferase center is made of rRNA and it is the site where peptide bonds are formed. RNase P is another catalytic RNA which is special because it works as a multiple turnover enzyme in trans during the processing of pre-tRNA molecules.

It is also found that short ribozymes can cleave specific RNA sequences, so these are used to block gene expression in some therapeutic areas. It can target cancer-related mRNA and retroviral RNA like HIV. Thus ribozymes show that catalytic activity is not limited only to proteins, and RNA can also function as an enzyme in living systems.

Structure of Ribozymes

Ribozymes have a specific three-dimensional structure, and it is the folded RNA chain that gives the catalytic activity. It is the single-stranded RNA that forms different secondary and tertiary patterns, and these patterns is maintained by base-pairing, junctions, and pseudoknot formation. The structure is mainly made of helices, and these helices stack end-to-end or associate side-by-side to make the complete architecture. It is the arrangement of these helices that brings the catalytic groups close together so that the cleavage site attains the in-line orientation needed for phosphoryl transfer. Metal ions like Mg²⁺ are also present in different pockets, and they stabilize the structure and help in catalysis.

The primary chain of RNA folds into stems, loops, bulges and junctions, and these parts interact to make the tertiary fold. It is the folded structure that forms the active site, and this active site positions the nucleobases and other functional groups for the catalytic step. The ribozyme structure is therefore a combination of helical domains, pseudoknots and specific tertiary contacts that hold the catalytic center in the correct geometry.

Some of the important structural types are–

- Hammerhead Ribozyme– It is made of three helices called stem I, stem II and stem III, and these stems meet at a central core. The core has conserved nucleotides that form the catalytic part. In natural hammerhead ribozymes, extra sequences are present that help in making a tertiary contact between the loop of stem II and the bulge of stem I. This contact changes the shape of stem I and places the cleavage nucleotide correctly for the reaction.

- Ribosome (Peptidyl Transferase Center)– The catalytic center of ribosome is made only of rRNA. It is present in the large subunit, especially in domain V of 23S rRNA. Protein molecules stay at the outer part and do not enter the active region. The 2′-OH group of A76 of tRNA is an important part of the structure because it is placed next to the P-site ester bond for peptide bond formation.

- Hairpin Ribozyme– This ribozyme has four helices arranged in a four-way junction. These helices form two coaxial stacks, where helix D stacks on A, and helix C stacks on B. The active center is made when Loop A and Loop B come close. The ribose zipper formed by nucleotides like A10/G11 and A24/C25 gives stability to the catalytic core.

- HDV Ribozyme– The HDV ribozyme is made of five helices P1.1, P1, P2, P3, and P4. These helices form a double pseudoknot structure. There are two coaxial stacks, and the active center lies at the meeting point of P1, P1.1 and P3. The nested pseudoknots give it a compact and stable folding.

- glmS Ribozyme– It has three coaxial stacks that lie almost parallel. The core part is formed by a double pseudoknot made by helices P2.1 and P2.2. The scissile phosphate is present in P2.2, and this region also forms the binding site for glucosamine-6-phosphate, which works as a cofactor.

- Twister Ribozyme– It contains three stems (P1, P2, P4) joined by loops. Two pseudoknots (PK1 and PK2) are also present. The active center is placed in the major groove where PK2 and P2 stack. The nucleotides around the cleavage region are forced apart which helps in creating the in-line attack arrangement.

- Pistol Ribozyme– This ribozyme has three stems P1, P2 and P3 with one pseudoknot. The P1 stem stacks with the pseudoknot which helps in forming the active region.

- Group I and Group II Introns– These are large self-splicing ribozymes. Group I introns have conserved stems P1 to P9 and conserved regions called P, Q, R, and S. Group II introns also have specific conserved domains that fold to make a catalytic center for self-splicing.

Thus the structure of ribozymes is mainly helical, stabilized by pseudoknots and metal ions, and it is the folding pattern that forms the active site for catalysis.

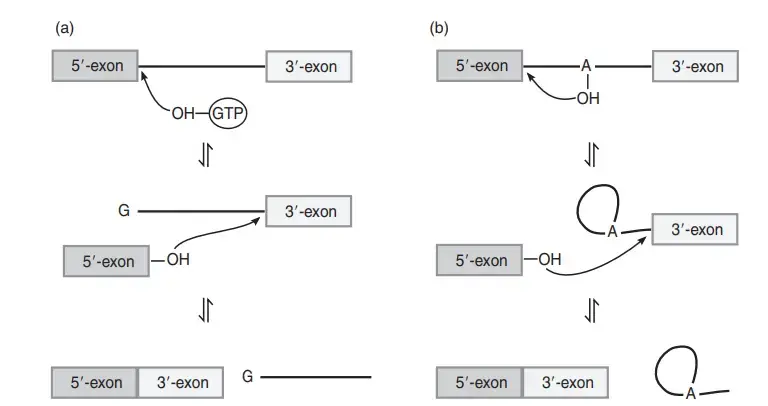

Splicing pathways of group I and II introns and the spliceosome

Group I

- In the first step, the 3′-OH group of an external GTP is used, and it is the process where this GTP attacks the phosphate at the 5′ splice site releasing the 5′ exon.

- The 3′-OH of the released 5′ exon then attacks the 3′ splice site, and this reaction forms a new bond joining the two exons.

- The linkage between the intron and the 3′ exon is broken in the final step, and the intron comes out as a linear RNA molecule with one guanosine added at its 5′ end.

Group II

- In the first step, the 2′-OH group of a branch point adenosine present inside the intron attacks the phosphate at the 5′ splice site. The 5′ exon is released, and it is the process where a lariat-shaped intron structure is formed.

- The 3′-OH of the 5′ exon now attacks the 3′ splice site, and this reaction joins the two exons in a continuous RNA chain.

- The intron is finally released in the lariat form, and the entire pathway is reversible similar to the group I intron reactions.

Types of Ribozymes

There are the different types of ribozymes such as;

- RNase P Ribozyme

- Hammerhead ribozymes

- GIR1 branching ribozyme

- hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme hatchet ribozyme

- Pistol ribozyme

- VS ribozyme

- Twister ribozymes

- Twister sister ribozyme

- Group 1 introns

- Group2 introns

1. RNase P ribozyme

- RNase P is an RNA processing endonuclease, and it is present in all cells and organelles where tRNA synthesis occur. It is mainly involved in removing the 5′ leader sequence from pre-tRNA molecules.

- The enzyme is a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex where an RNA subunit and a protein subunit are present together. The RNA part is the catalytic part, and the protein part is required for proper cleavage at physiological Mg²⁺ concentration.

- In high Mg²⁺ conditions, the RNA component alone can cleave precursor tRNA in vitro, showing that the catalytic activity is mainly due to RNA.

- During substrate recognition, the acceptor stem of pre-tRNA binds with the enzyme through an external guide sequence (EGS), and this interaction helps in positioning the cleavage site.

- The 5′-CCA-3′ region at the 3′ end of the EGS is important for cleavage, and by designing a suitable EGS this system can be applied to other RNA targets.

- RNase P acts as a true enzyme in trans because it binds the substrate, cleaves it, and comes back unchanged for another round of reaction.

- The enzyme releases products through a hydrolytic cleavage which makes a 5′-monophosphate and a 3′-OH at the ends.

- It is considered an ancient catalytic RNA complex and is closely related to RNase MRP found in eukaryotes, which work in rRNA processing and mitochondrial functions.

2. Hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme

- HDV ribozyme is a small self-cleaving RNA associated with Hepatitis Delta Virus, and it is required for the self-scission steps during rolling-circle replication of the viral RNA genome.

- It is found in both genomic and antigenomic strands, and each copy helps in processing long RNA concatemers into short unit-length forms needed for viral replication.

- HDV-like ribozyme motifs are also present in many organisms, and these are found in some mammalian genes and also in 5′ UTR regions of retrotransposons.

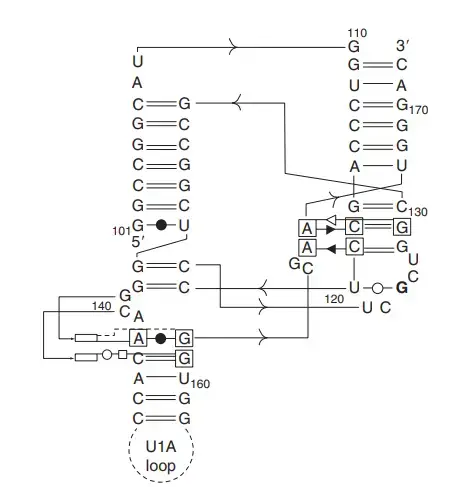

- The ribozyme is about 85 nucleotides long and it contains five helices (P1.1, P1, P2, P3, P4). These helices form two coaxial stacks and a nested double-pseudoknot structure.

- The active site is formed at the junction of P1, P1.1 and P3, and the structure is very stable even in strong denaturing conditions.

- Catalysis is carried out by general acid–base mechanism, and the scission produces a 2′–3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH group.

- The invariant cytosine (C75) works as the general acid in the active site, and a hydrated Mg²⁺ ion acts as the general base to activate the 2′-OH group for nucleophilic attack.

- It is an obligate metalloenzyme under normal biological conditions because divalent metal ions are required for efficient cleavage.

- The HDV ribozyme can be engineered as trans-acting, but the activity is mainly efficient in cis-cleaving forms due to natural structural constraints.

- It has therapeutic importance because it is essential for HDV viability, and engineered ribozymes based on this structure have been tested against viral RNAs in different experimental systems.

3. Hammerhead Ribozyme

- It is a small self-cleaving RNA motif which catalyses cleavage and ligation at a specific site of an RNA molecule, and it is naturally found in viroids and plant satellite RNAs where it helps in self-scission during rolling-circle replication.

- The minimal hammerhead ribozyme has a central conserved core of around 15 nucleotides, and this core is connected with three helices called stem I, stem II and stem III. These stems are separated by short conserved linkers.

- In naturally occurring hammerhead ribozymes, extra peripheral sequences form a tertiary contact between distal parts of stem I and stem II, and this tertiary interaction helps in making the active conformation with a higher cleavage rate.

- The ribozyme cleaves the substrate RNA to produce a 2′–3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′-hydroxyl group at the cleavage site. The cleavage site is usually present at the 3′ end of a GUC triplet.

- The general base in the reaction is G12 which activates the 2′-OH of the cleavage nucleotide, and the general acid is the 2′-OH group of G8 which donates a proton to the leaving group.

- Metal ions like Mg²⁺ help in stabilising the folded structure, but at high monovalent ion concentration the ribozyme can also function without divalent ions.

- The ribozyme can act as cis-cleaving in its natural form, but it can also be separated into an enzyme strand and a substrate strand to function in trans without altering its own sequence.

- Hammerhead ribozymes are classified as type I, type II and type III based on the position of their 5′ and 3′ ends in the three stems. Type I is most common in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and plant pathogens.

- The conserved sequences 5′-CUGAXGA-3′ and 5′-GAAA-3′ near the catalytic center are important for the cleavage step, and any change in these regions can reduce activity.

- These ribozymes have been used in gene regulation because they can cleave mRNA in 3′ UTR regions, and engineered hammerhead ribozymes are studied for therapeutic uses in cancer and viral infections.

4. Hairpin Ribozyme

- The hairpin ribozyme is a small self-cleaving RNA found in the satellite RNAs of plant viruses like TRSV, CYMV and ARMV, and it helps in processing long RNA molecules formed during rolling-circle replication.

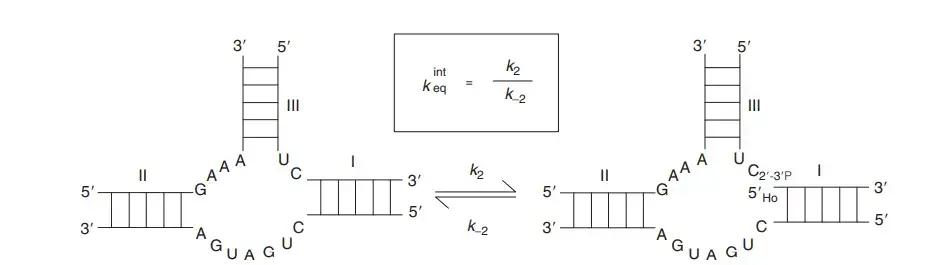

- It catalyses both cleavage and ligation reactions, and these reactions convert long multimeric RNA into unit-length linear or circular forms which are needed for the next replication cycle.

- Its secondary structure is made of four helices named A, B, C and D that are arranged in a four-way junction, and helices D and A form one coaxial stack while helices C and B form another.

- The active site is formed when Loop A and Loop B come close, and this region has a ribose-zipper type interaction involving nucleotides like A10/G11 and A24/C25 which helps in forming the catalytic geometry.

- The cleavage site is present in helix A, and the nucleotide at position G+1 is held in an extruded position which makes the in-line attack possible for the 2′-OH nucleophile.

- The cleavage reaction gives a 2′-3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH product, and the reaction is reversible, so the ribozyme can also carry out ligation in vitro.

- The general base for the reaction is G8 which activates the 2′-OH group, and the general acid is A38 which donates a proton to the leaving group during cleavage.

- The ribozyme does not need metal ions directly for catalysis; monovalent ions are enough, and Mg²⁺ helps mainly in stabilizing the folded structure.

- The hairpin ribozyme can be engineered to act in trans, and the substrate usually has an RYN*GUC sequence where cleavage occurs at the marked site.

- It has been tested for targeting viral RNA such as HIV-1 RNA, and engineered forms have been used to study substrate cleavage and ligation in different experimental systems.

5. Group I introns

- Group I introns are large self-splicing RNA molecules, and these introns remove themselves from precursor RNA without the need of proteins or external energy.

- These introns were first discovered in Tetrahymena thermophila rRNA precursor, and the excised intron was found as a linear RNA that could also cyclize on its own.

- They are usually 200–1500 nucleotides long and are widely present in bacteria, bacteriophages, eukaryotic viruses, mitochondria, chloroplasts and in nuclear rDNA of fungi, plants and algae.

- Group I introns are classified into different types like IA, IB, IC, ID and IE based on conserved structures, and these types are further divided into many subgroups.

- The intron structure contains ten paired segments (P1–P10), and the catalytic core is formed by two domains called P4–P6 and P3–P9 which hold the active region.

- The splice sites are aligned by the internal guide sequence (IGS) and this IGS forms P1 at the 5′ splice site and P10 at the 3′ splice site.

- A guanosine binding site is formed in the P7 helix, and the exogenous guanosine cofactor binds here to start the cleavage reaction.

- In the first step, the 3′-OH of the external guanosine attacks the 5′ splice site and releases the 5′ exon, and the guanosine becomes attached to the 5′ end of the intron.

- In the second step, the 3′-OH of the 5′ exon attacks the 3′ splice site and joins with the 3′ exon, releasing the intron as a linear RNA with the added guanosine.

- The catalytic mechanism needs Mg²⁺ ions, and two Mg²⁺ ions are usually found close to the scissile phosphate to assist the reaction.

- Some Group I introns contain homing endonuclease genes which help the intron move to intron-lacking alleles through DNA repair mechanisms.

- These introns can also spread by reverse splicing into RNA molecules, followed by reverse transcription and insertion into DNA.

- The excised Tetrahymena intron can act in trans, and it is able to perform reactions like cleavage or ligation on separate substrate RNAs.

- Group I introns are considered potential antifungal targets because they are absent in humans but present in many pathogenic fungi, and some antibiotics or small molecules can inhibit their splicing.

6. Group II introns

- Group II introns are large self-splicing RNA molecules found mainly in bacteria, mitochondria and chloroplasts of fungi, plants and protists, and these introns remove themselves from precursor RNA without external energy.

- They are usually 300–3000 nucleotides long, and many of them contain internal ORFs that can encode maturases, reverse transcriptases or homing endonucleases which help in splicing and movement of the intron.

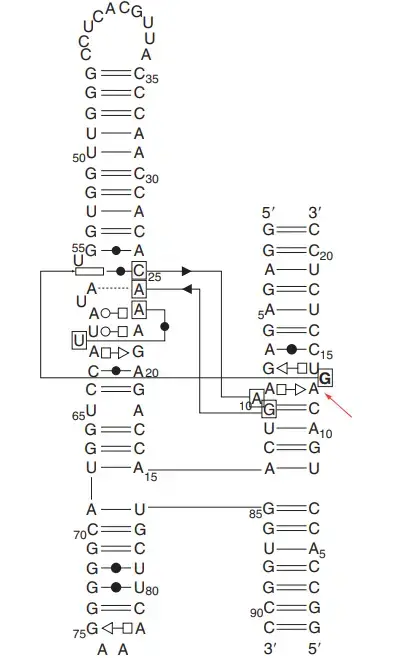

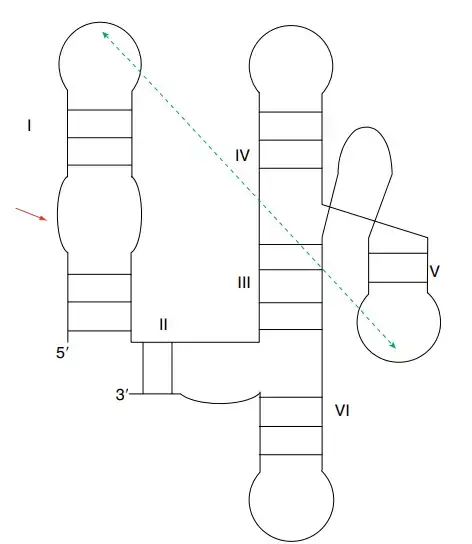

- The intron structure has six domains (I–VI) arranged around a central core, and domains I and V are essential because they hold the catalytic parts of the RNA.

- Domain V contains a conserved hairpin of about 34 nucleotides with a GNRA loop and a two-nucleotide bulge, and Domain VI carries the branch point adenosine that starts the first transesterification reaction.

- The exon sequences base pair with intron binding sites called IBS1 and IBS2, and these match with the EBS1 and EBS2 regions in Domain I, helping in aligning the splice sites.

- In the first step of splicing, the 2′-OH group of the conserved adenosine in Domain VI attacks the 5′ splice site forming a lariat with a 2′–5′ linkage.

- In the second step, the 3′-OH of the 5′ exon attacks the 3′ splice site and joins the exons, releasing the intron as a lariat molecule.

- Sometimes a water molecule can start the reaction, and in this case the intron is released as a linear RNA instead of a lariat.

- These introns need Mg²⁺ ions for catalysis, and the two-metal-ion mechanism is used to activate the attacking 2′-OH and stabilize the leaving group during the reaction.

- In vivo splicing often requires the help of intron-encoded maturase proteins or host proteins because correct folding of the large intron structure is difficult without assistance.

- Group II introns are considered the ancestors of the eukaryotic spliceosome as both systems use the same two-step transesterification and make the same lariat intermediate.

- Structural studies show clear similarity between the active sites of Group II introns and the spliceosomal RNA core, supporting the evolutionary link.

7. Group -I- like ribozymes (GIR1) branching ribozyme

- GIR1 is a Group I-like ribozyme found in Didymium iridis, and it is also called the lariat capping ribozyme because it forms a small lariat that works as a protective 5′ cap.

- It shows sequence similarity to Group I introns, but its catalytic pathway is different because it forms a lariat rather than a linear intron product.

- The reaction carried out by GIR1 is a branching reaction where a 2′,5′-phosphodiester bond is formed, and this makes a three-nucleotide lariat structure.

- The lariat product remains attached at the 5′ end of the downstream mRNA, and this small branched structure protects the mRNA from degradation.

- Though GIR1 looks similar to Group I introns in sequence, its mechanism is more similar to Group II introns because it uses a branching step to form the lariat.

- The ribozyme is part of an intron-encoded system where the protected mRNA usually encodes an endonuclease needed for mobility of the intron.

- Structural studies show that GIR1 ribozymes form a separate family that may share an old evolutionary connection with Group I introns but has developed a distinct lariat-forming activity.

8. Glucosamine-6-phosphate riboswitch ribozyme (gim ribozyme)

- The glmS ribozyme is a self-cleaving RNA motif found in the 5′-UTR of the glmS gene in many Gram-positive bacteria, and it controls gene expression by responding to the metabolite glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P).

- It works in a negative feedback system because when GlcN6P concentration becomes high, the metabolite binds the ribozyme and causes self-cleavage of the mRNA, which leads to degradation of the message and reduced synthesis of the GlmS enzyme.

- The cleavage reaction produces a 2′-3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH group, and the 5′-OH end becomes a substrate for RNase J which breaks down the processed transcript.

- The structure of the ribozyme contains three coaxial stacks arranged nearly parallel (P1 with P3.1, P4 with P4.1 and P2.1), and the catalytic core is made by a double pseudoknot involving helices P2.1 and P2.2.

- The P2.2 helix contains the scissile phosphate and helps in forming the binding pocket for the GlcN6P cofactor, and this pocket is an open solvent-accessible cleft formed mostly by the P2 loop.

- The GlcN6P molecule sits inside the pocket stacked over G1, and its phosphate group forms hydrogen bonding with N1 of G1 and also binds a Mg²⁺ ion.

- The ribozyme structure is rigid and already in an in-line arrangement for cleavage, so GlcN6P acts mainly as a chemical cofactor rather than causing a conformational change like normal riboswitches.

- The amine group of GlcN6P is necessary for catalysis and works as the general acid which protonates the 5′-O leaving group.

- A conserved guanosine residue (such as G40 or G33 depending on species) acts as the general base which activates the 2′-OH nucleophile of the substrate strand.

- Other amine-containing molecules like serinol or Tris can also activate the ribozyme in vitro, but GlcN6P gives much higher activity and supports the natural regulation of the glmS gene.

9. Hatchet ribozyme

- The hatchet ribozyme is a small self-cleaving RNA motif discovered by bioinformatic analysis of conserved RNA structures, and its discovery along with pistol and twister ribozymes shows that many catalytic RNAs are still unknown.

- Its secondary structure contains four stems named P1, P2, P3 and P4. Stems P1 and P2 are linked by three conserved residues, and stems P2, P3 and P4 are joined by two internal loops called L2 and L3.

- Loop L2 contains most of the conserved nucleotides important for catalysis, and the product-state structure appears compact and pseudo-symmetrical.

- The cleavage site lies at the 5′ end of stem P1, and this distal position is similar to what is seen in HDV-like ribozymes.

- Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) are necessary for self-cleavage, and Mg²⁺ helps in the correct folding of the ribozyme.

- Modeling studies suggest that G31 may act as the general base through its N7 position to activate the 2′-OH nucleophile, and replacing G31 with 7-deazaguanosine completely stops cleavage activity.

- Although Mg²⁺ is essential for the reaction to occur efficiently, it may not directly participate in the chemistry of the active site, and the mechanism resembles that of an HDV-type metalloenzyme.

- The hatchet ribozyme is useful in synthetic biology because it cleaves at the outer region of P1, and this feature makes it possible to use it without interfering with guide RNA structure in systems like CRISPR.

10. Pistol ribozyme

- The pistol ribozyme is a small self-cleaving RNA motif found by comparative genomics, and it is one of the newly identified nucleolytic ribozymes along with twister, twister-sister and hatchet ribozymes.

- Its secondary structure is made of three helices named P1, P2 and P3 together with a pseudoknot, and these parts are joined by loops L1, L2 and L3.

- The P1 stem stacks with the pseudoknot in the tertiary fold, and this arrangement helps in forming the in-line geometry needed for cleavage.

- The scissile phosphate lies at a sharp turn between P2 and P3, and the bases on both sides of this phosphate are paired which opens up the backbone and supports the nucleophilic attack.

- The catalytic mechanism is similar to hammerhead ribozyme because a conserved guanosine works as the general base. In pistol ribozyme, G40 accepts a proton from the 2′-OH group and activates it.

- The main difference with hammerhead ribozyme is in the general acid step. The 2′-OH of the corresponding nucleotide (A32) does not work as the general acid here.

- Instead of that, a hydrated metal ion works as the general acid, and Mg²⁺ is seen bound near G33 with a water molecule placed close to the leaving group for protonation.

- The cleavage rate depends on the pKa of the metal ion used in the reaction, which supports the idea that the coordinated water molecule is giving the proton to the 5′-oxygen leaving group.

- The reaction gives the usual products of nucleolytic ribozymes which is the 2′–3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH group, and the pseudoknot fold is important for arranging the active site.

11. VS ribozyme

- The VS ribozyme is a self-cleaving RNA found in the satellite RNA of the Varkud plasmid of Neurospora, and it helps in the processing of the long RNA transcripts during replication.

- It catalyses a transesterification reaction that gives a 2′–3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH group, similar to other small nucleolytic ribozymes.

- It is the largest known nucleolytic ribozyme with about 155 nucleotides, and its structure contains seven helices (1–7) arranged into three three-way junctions.

- The cleavage site is present in the inner loop of stem 1, and the catalytic site is formed by interactions between loops present in stem 1 and stem 6.

- A kissing-loop interaction between the GUC sequence of stem-loop 1 and the GAC sequence of stem-loop 5 is important for making the active site and for proper positioning of the cleavage region.

- The ribozyme structure can also form a dimer where substrate helices are exchanged which results in two trans-active sites, as shown by some crystal structure studies.

- The general base is G638 which activates the 2′-OH nucleophile, and the general acid is A756 which donates a proton to the leaving group.

- Mg²⁺ ions are important for the reaction, and they interact with the scissile phosphate and help in activating G638, although high monovalent ion concentration can also support catalysis.

- Only a small proportion of molecules are active at neutral pH because the reaction depends on special protonation states of guanine and adenine residues in the active site.

- A trans-cleaving form of the VS ribozyme can be made by separating the P1 stem-loop from the catalytic core, and this system has been tested for trimming 3′ ends of RNA, although activity in trans is usually low.

12. Twister ribozyme

- The twister ribozyme is a small self-cleaving RNA motif identified by bioinformatic searches, and it is widely present in many bacterial and eukaryotic genomes.

- Its secondary structure contains three stems named P1, P2 and P4, and these stems are connected by loops L1, L2 and L4. Two pseudoknots called PK1 and PK2 are present which help in forming the complete fold.

- The overall structure forms an inverted double pseudoknot, and some variants also contain extra stems like P3 or P5.

- The active site lies in the major groove formed by the PK2(T1)–P2 helix stack, and this region is stabilized by base stacking and the two pseudoknots which help in forming the in-line geometry needed for cleavage.

- The cleavage reaction occurs between a conserved A and U near stem P1, and the ribozyme gives a 2′–3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH product.

- The conserved G33 acts as the general base, and it activates the 2′-OH nucleophile by removing a proton. G33 also helps in stabilizing the transition state through hydrogen bonding.

- The general acid is the adenine residue at position +1, and its N3 group donates a proton to the leaving group. The local environment increases the pKa of this adenine so that it can function effectively.

- Mg²⁺ ions help in folding of the ribozyme and may stabilize the transition state, and a Mg²⁺ ion has been observed near the scissile phosphate in some structures.

- Mutation of G33 to inosine reduces the cleavage rate by several hundred fold, showing the importance of this base in catalysis.

- Twister-type motifs also include the twister-sister ribozyme which shares some structural features but does not contain the full double pseudoknot arrangement seen in twister ribozymes.

13. Twister sister ribozyme

- The twister sister ribozyme is a small self-cleaving RNA motif discovered by comparative genomics, and it belongs to the same new group of nucleolytic ribozymes as twister, pistol and hatchet ribozymes.

- It catalyses site-specific cleavage that produces a 2′–3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH group, and it is found widely in different organisms based on sequence searches.

- The TS ribozyme shares some sequence and secondary structure similarity with the twister ribozyme, but it does not contain the double pseudoknot pattern that is seen in twister motifs.

- Structural studies show that Mg²⁺ ions help in bringing several conserved loop nucleotides toward the catalytic center, and this arrangement is needed for forming the active site.

- In one crystal form, nucleotides C62 and A63 at the cleavage region are splayed apart, and the scissile phosphate is held by hydrogen bonds involving G5, a non-bridging oxygen, and a water molecule bound to a Mg²⁺ ion.

- The conformation around the scissile phosphate is often not in an in-line position, suggesting that the active center may require a major rearrangement before catalysis can occur.

- The activity increases with Mg²⁺ concentration and shows a log-linear dependence on the pKa of the divalent metal ion which indicates direct participation of a hydrated metal ion in the cleavage step.

- The hydrated metal ion is expected to act as the general base by activating the 2′-OH nucleophile, and this is supported by the position of a Mg²⁺ ion bound to a cytosine located just 5′ to the cleavage site.

- Mutations show that C7 is important for activity, and it is suggested that C7 may act as the general acid or bind a metal ion that functions as the acid when the active site rearranges into an in-line geometry.

- The TS ribozyme is therefore grouped with HDV-type ribozymes which use a metal ion and a cytosine nucleobase together in the general acid-base catalysis.

14. Artificial Ribozymes

- Artificial ribozymes are catalytic RNA molecules made in laboratory systems, and these are selected or engineered to show new activities or higher efficiency than natural ribozymes.

- The SELEX method is mainly used where a large pool of random RNA or DNA molecules is screened, and molecules showing a desired catalytic activity are selected and amplified for further rounds.

- Mutagenesis steps like error-prone PCR or reverse transcription can be used to create diverse RNA libraries which help in selecting improved variants.

- Advanced systems like in vitro compartmentalization allow selection from very large pools, and ribozymes like B6.61 polymerase were isolated using this method.

- Artificial RNA polymerase ribozymes have been developed from a Class I ligase scaffold, and improved forms like R18, B6.61, tC19Z or tC9Y can extend RNA strands of many nucleotides with good fidelity.

- Some variants like 24-3 ribozyme are able to copy other RNA molecules and have been used to make an RNA version of PCR by amplifying RNA templates thousands of times.

- Other ribozymes produced by directed evolution can catalyse reactions like redox chemistry, aminoacylation, peptide bond formation, and carbon–carbon bond formation such as the Diels–Alder reaction.

- Aptazymes are engineered by fusing an aptamer region with a ribozyme region so that ligand binding controls the catalytic activity, and these are used as biosensors or regulatory switches.

- Self-cleaving motifs like HDV, hammerhead, pistol and twister ribozymes have been adapted into aptazymes for controlling gene expression in artificial systems.

- Artificial ribozymes are used for targeted cleavage of mRNA or viral RNA in gene therapy, and these ribozymes can silence disease-related genes in cancer or viral infections.

- Delivery of synthetic ribozymes has been improved by using low molecular weight polyethylenimine (LMW-PEI) which stabilises the RNA and helps in cellular uptake without chemical modification of the ribozyme.

Mechanisms of ribozyme catalysis

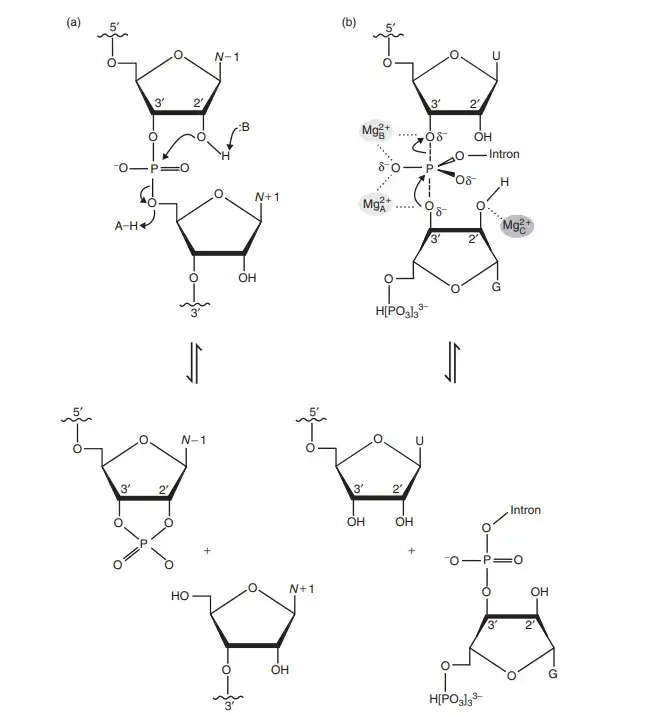

Core Chemical Mechanism: 2′-O-Transphosphorylation

It is the most common mechanism used by natural ribozymes for cleavage or ligation of RNA strands. The reaction is initiated when the O2′ group of ribose perform a nucleophilic attack on the phosphorus atom of the adjacent phosphate. This step gives a pentavalent transition state having trigonal bipyramidal geometry. It is the state where the O2′, phosphorus, and O5′ groups stay arranged in an in-line form. The reaction is completed when the O5′ group leaves and forms a 5′-OH, and the upstream nucleotide forms a 2′,3′ cyclic phosphate.

Four Main Catalytic Strategies

These are the major features involved in ribozyme catalysis–

- In-line Geometry (α)

It is the arrangement of the O2′ nucleophile, P atom and O5′ leaving group in the required linear fashion for effective attack. - Nucleophile Activation (γ)

The 2′-OH is activated by deprotonation. This forms the alkoxide ion which is a stronger nucleophile. - Leaving Group Stabilization (δ)

It is the process where the negative charge on the O5′ leaving group is neutralised or protonated to form a better leaving group. - Transition State Stabilization (β)

The accumulating charge on the non-bridging phosphate oxygen atoms is stabilised.

These strategies mostly work in a combined manner. The general acid and general base used by ribozymes perform proton transfer to assist O2′ activation and O5′ stabilization.

Catalytic Features of Different Ribozyme Families

It is observed that different ribozymes use different nucleobases or metal ions as the general acid or general base. Some of the main features are–

- Hammerhead ribozyme – G12 act as general base. The 2′-OH of G8 act as general acid.

- Hairpin ribozyme – G8 act as general base. A38 act as general acid.

- HDV-like ribozyme – Metal ion (M²⁺-OH⁻) act as general base. C75 act as general acid.

- glmS ribozyme – Guanine act as general base. Glucosamine-6-phosphate act as general acid.

- Pistol ribozyme – G40 act as general base. Hydrated metal ion act as general acid.

- Twister ribozyme – G33 act as general base. A+1 act as general acid.

- VS ribozyme – G638 act as general base. A756 act as general acid.

- Group I introns – Two metal ions (Mg²⁺) take part in catalysis by the two-metal-ion mechanism.

- Ribosome – It uses substrate-assisted catalysis where the 2′-OH of A76 of tRNA help in proton transfer.

- RNase P – It uses two Mg²⁺ ions and water acts as the nucleophile.

General Acid-Base Catalysis

It is the most important catalytic process used by ribozymes. Conserved nucleobases (A, G, or C) act as proton donors or acceptors. It is the process where pKa of nucleobases is shifted near the physiological range. This helps the active site to hold the correct protonation state for catalysis. Guanine is commonly used as the general base in many natural ribozymes.

Metal Ion Catalysis

Divalent metal ions, mostly Mg²⁺, are important in ribozyme activity. These metals are required either for stabilizing the ribozyme structure or for direct catalytic work.

- Small self-cleaving ribozymes like hammerhead and hairpin use Mg²⁺ mainly for structural support.

- Metalloenzymes such as Group I introns, RNase P, HDV and pistol ribozymes use Mg²⁺ for direct chemical catalysis.

- Two-metal-ion mechanism is used by Group I introns and RNase P, where two Mg²⁺ ions stabilize the transition state and help in phosphoryl transfer.

Substrate or Cofactor Assistance

Some ribozymes need additional molecules.

The glmS ribozyme uses glucosamine-6-phosphate as a coenzyme. Its amine group act as the general acid. In ribosome, the 2′-OH group of P-site tRNA is necessary for proton transfer and plays a more important role than rRNA nucleobases.

Functions of Ribozymes

- It is involved in protein synthesis where the rRNA of the large ribosomal subunit catalyzes peptide bond formation.

- It helps in RNA processing because RNase P cleaves the 5′ leader sequence of pre-tRNA.

- It is used in self-splicing of introns as Group I and Group II introns remove themselves and ligate the exons.

- It takes part in intron mobility since these introns can move inside genomes by reverse splicing or DNA homing.

- It performs self-cleavage reactions in viral and viroid replication producing unit-length RNAs during rolling-circle replication.

- The HDV ribozyme is required for the life cycle of Hepatitis Delta Virus.

- It regulates gene expression where glmS ribozyme act as metabolite-dependent riboswitch and degrade its own mRNA.

- It is involved in retrotransposon processing because HDV-like and hammerhead ribozymes help in RNA cleavage and ligation of these elements.

- It helps in mammalian gene regulation since conserved hammerhead ribozymes in 3′-UTR reduce gene expression by self-cleavage.

- It may regulate mRNA splicing and termination as seen in CPEB3 ribozyme and CoTC ribozyme.

- It can be engineered for gene silencing where synthetic ribozymes cleave specific RNA sequences.

- It is used in antiviral therapy by targeting viral RNAs like HIV-1, HCV, SARS-CoV and influenza viruses.

- It is applied in cancer research since ribozymes can reduce expression of cancer-related genes like HER-2/neu or PTN.

- It is used in functional genomics for studying and controlling gene expression in vivo.

- Synthetic ribozymes can catalyze RNA replication where RNA polymerase ribozymes synthesize RNA strands.

- Aptazymes are formed by combining ribozymes with aptamers and act as molecular biosensors.

- Artificial ribozymes can catalyze different chemical reactions such as ligation, phosphorylation, aminoacylation, peptide bond formation and redox reactions.

- It is also used in forming carbon-carbon bonds like Diels–Alder reaction or aldol condensation under in-vitro conditions.

FAQ

1. What are ribozymes?

Ribozymes are catalytic RNA molecules. It is the process where RNA itself act as an enzyme and carry out cleavage or ligation reactions of RNA strands. These are referred to as catalytic RNAs.

2. What is the function of ribozymes?

The main function of ribozymes is to catalyze phosphoryl transfer reactions like RNA cleavage, ligation and splicing. It is also involved in protein synthesis, RNA processing, viral replication, and gene regulation.

3. Are ribozymes considered enzymes?

Yes, ribozymes are considered enzymes because they catalyze biochemical reactions. The catalytic activity is performed by RNA instead of protein.

4. Where are ribozymes found in the cell?

Ribozymes are found in different cellular locations such as mitochondria, nucleus, and cytoplasm. The ribosome is present in the cytoplasm, and RNase P is present in the nucleus and mitochondria.

5. What are some examples of ribozymes?

Some common examples are hammerhead ribozyme, hairpin ribozyme, HDV ribozyme, RNase P, Group I intron, Group II intron, and the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center.

6. Who discovered ribozymes?

Ribozymes were discovered by Thomas Cech and Sidney Altman. It is observed that RNA can catalyze reactions without protein.

7. What is the RNA world hypothesis in relation to ribozymes?

It is the hypothesis which states that early life used RNA for both genetic storage and catalytic functions. Ribozymes are considered molecular fossils of this RNA world.

8. How do ribozymes catalyze biochemical reactions?

Ribozymes catalyze reactions by forming in-line geometry, activating nucleophiles, stabilizing leaving groups, and holding the transition state. It is mostly performed by general acid-base catalysis and sometimes metal ions are used.

9. What is the difference between ribozymes and protein enzymes?

The main difference is that ribozymes are made of RNA while protein enzymes are made of amino acids. Ribozymes use nucleobases and metal ions for catalysis, and protein enzymes use amino acid side chains.

10. Can ribozymes self-replicate?

Some synthetic ribozymes can perform RNA polymerase activity and replicate short RNA sequences. Natural ribozymes do not show complete self-replication.

11. What are the different types of ribozymes?

Different types include self-cleaving ribozymes (hammerhead, hairpin, HDV, pistol, twister), splicing ribozymes (Group I and Group II introns), catalytic rRNA, and RNase P.

12. What role do ribozymes play in protein synthesis?

The ribosome use rRNA to catalyze peptide bond formation. It is the peptidyl transferase activity located in the large subunit rRNA.

13. What are the potential therapeutic uses of ribozymes?

Ribozymes are used for gene silencing, antiviral therapy, and cancer treatment. It can cleave specific RNA sequences and reduce unwanted gene expression.

14. Do ribozymes require metal ions for their catalytic activity?

Some ribozymes require metal ions like Mg²⁺ for folding or direct catalysis. Others are metal-independent and use nucleobases only.

15. How were ribozymes discovered?

Ribozymes were discovered when RNA molecules were observed to catalyze reactions without protein involvement. The self-splicing Group I intron and the catalytic activity of RNase P led to this discovery.

- Aigner, A., Fischer, D., Merdan, T., & Brus, C. (2003). Delivery of unmodified bioactive ribozymes by an RNA-stabilizing polyethylenimine (LMW-PEI) efficiently down-regulates gene expression. Gene Therapy, 9(24), 1700–1707. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3301839

- Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Walter, P. (2002). The RNA World and the Origins of Life. In Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science.

- Alonso, D., & Mondragón, A. (2021). Mechanisms of catalytic RNA molecules. Biochemical Society Transactions, 49(4), 1529–1535. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20200465

- An Ontology for Facilitating Discussion of Catalytic Strategies of RNA-Cleaving Enzymes. (2019). ACS Chemical Biology, 14(6), 1068–1076. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.9b00202

- Distinct reaction pathway promoted by non-divalent-metal cations in a tertiary stabilized hammerhead ribozyme. (2007). RNA. PMC1869042.

- Gomes, R. M. O. da S., da Silva, K. J. G., & Theodoro, R. C. (2024). Group I introns: Structure, splicing and their applications in medical mycology. Genetics and Molecular Biology, 47(Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2023-022

- Han, K., & Liang, Z. (2010). Design Strategies for Aptamer-Based Biosensors. Sensors, 10(5), 4541–4557. https://doi.org/10.3390/s100504541

- Jimenez, R. M. (2015). Chemistry and biology of self-cleaving ribozymes. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 40(11), 648–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2015.09.001

- Joyce, G. F., & Szostak, J. W. (2018). Protocells and RNA Self-Replication. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 10(9). https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a034801

- Lawrence, M. S., & Bartel, D. P. (2005). New ligase-derived RNA polymerase ribozymes. RNA, 11(8), 1173–1180. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.2110905

- Lilley, D. M. J. (2015). RNA catalysis—is that it? RNA. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.049874.115

- Lilley, D. M. J. (2019). Classification of the nucleolytic ribozymes based upon catalytic mechanism. F1000 Research, 8(F1000 Faculty Rev-1462). https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.19324.1

- Martick, M., & Scott, W. G. (2006). Tertiary Contacts Distant from the Active Site Prime a Ribozyme for Catalysis. Cell, 126(2), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.036

- Moore, P. B., & Steitz, T. A. (2003). After the ribosome structures: How does peptidyl transferase work? RNA, 9(2), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.2127103

- Mutschler, H. (2019). The difficult case of an RNA-only origin of life. Biochemical Society Transactions. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20190105

- Nobel Prize Outreach. (n.d.). Press release: The 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Retrieved from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1989/press-release/

- Peng, H., Latifi, B., Müller, S., Lupták, A., & Chen, I. A. (2021). Self-cleaving ribozymes: substrate specificity and synthetic biology applications. Chemical Science, 2(5), 1370–1383. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cb00207k

- Saldanha, R., Mohr, G., Belfort, M., & Lambowitz, A. M. (1993). Group I and group II introns. FASEB J, 7(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.7.1.8422962

- Scott, W. G. (2013). The Hammerhead Ribozyme: Structure, Catalysis and Gene Regulation. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 120, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-381286-5.00001-9

- Serganov, A., & Patel, D. J. (2007). Ribozymes, riboswitches and beyond: regulation of gene expression without proteins. Nature Reviews Genetics, 8(10), 776–790. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2172

- Strobel, S. A. (2007). RNA Catalysis: Ribozymes, Ribosomes and Riboswitches. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 11(6), 636–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.09.010

- Tanner, N. K. (1999). Ribozymes: the characteristics and properties of catalytic RNAs. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 23(3), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00399.x

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Ribozyme. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ribozyme

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). RNA world. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RNA_world

- Wilson, T. J., Liu, Y., & Lilley, D. M. J. (2016). Ribozymes and the mechanisms that underlie RNA catalysis. Frontiers of Chemical Science and Engineering, 10(2), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11705-016-1558-2

- Zaher, H. S., & Unrau, P. J. (2007). Selection of an improved RNA polymerase ribozyme with superior extension and fidelity. RNA, 13(7), 1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.548807