What is High Throughput Sequencing (HTS)?

- High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS), often known as Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), represents a significant leap forward in genomic research. Unlike traditional Sanger sequencing, which uses the chain-termination method and is limited by low throughput and high costs, HTS enables the rapid and cost-effective sequencing of DNA and RNA on a grand scale.

- HTS technologies operate through parallel processing, allowing the simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA or RNA fragments. This contrasts sharply with the sequential nature of earlier sequencing methods, greatly enhancing both speed and efficiency. The process begins with the fragmentation of DNA or RNA into smaller pieces. Adapters or primers are then attached to these fragments, which are subsequently amplified to create clusters of identical sequences.

- Sequencing is carried out by determining the nucleotide sequence of each cluster. This is typically achieved using techniques such as sequencing-by-synthesis or sequencing-by-ligation, which involve detecting luminescently tagged nucleotides or their cleaved markers. This method allows for the comprehensive analysis of entire genomes or transcriptomes in a single run, compared to the single-sample throughput of Sanger sequencing.

- HTS encompasses several advanced platforms, including those from Illumina and Oxford Nanopore. These platforms can process millions of sequences per run, facilitating detailed genetic analyses such as whole genome sequencing (WGS), whole exome sequencing (WES), and targeted sequencing. Additionally, HTS is applied in transcriptome analysis and epigenome sequencing, providing a broader understanding of genetic information and its implications in health and disease.

- Overall, HTS has revolutionized genomic research by enabling high-throughput, detailed, and efficient sequencing of genetic material, thereby expanding our capabilities to study and understand complex genetic and biological systems.[ref – 4,9,1]

Working Principle of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS)

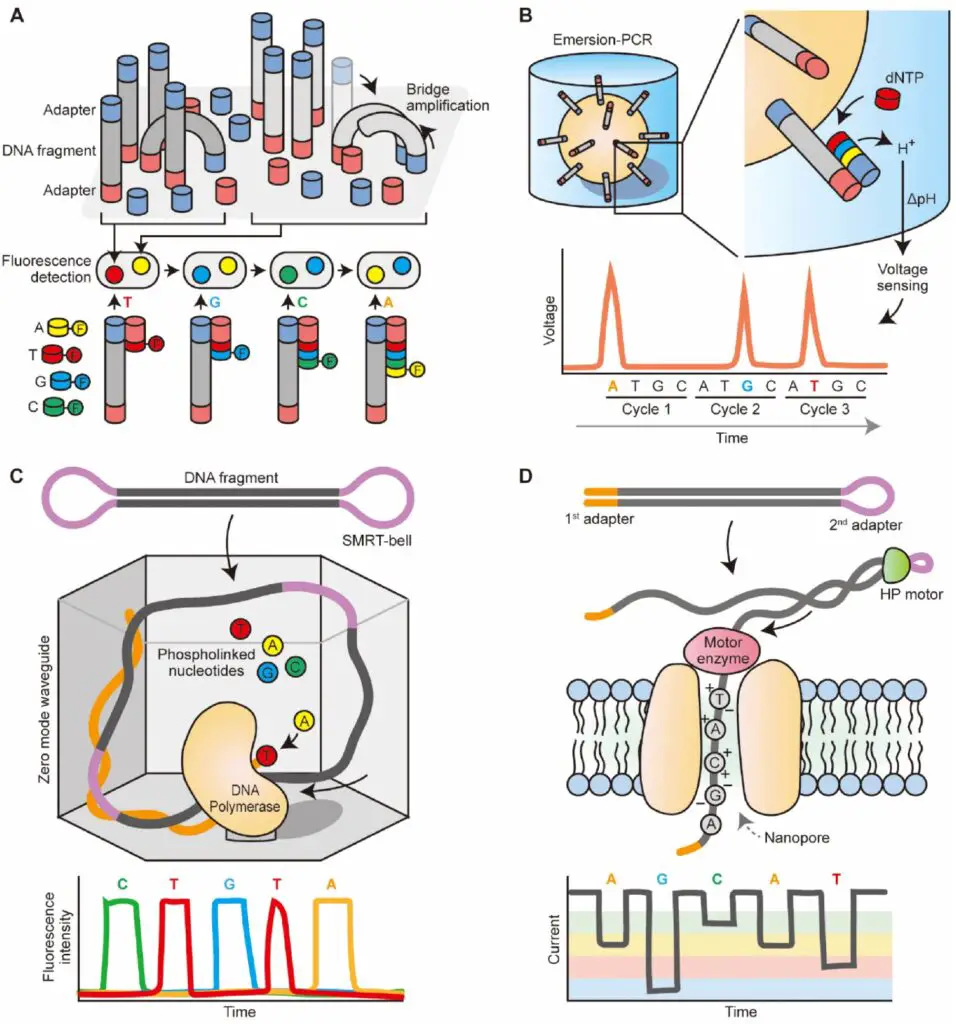

- High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) employs a principle of massively parallel sequencing to achieve extensive and rapid sequencing of genetic material. This principle is implemented through various generations of sequencing technology, each with distinctive methodologies.

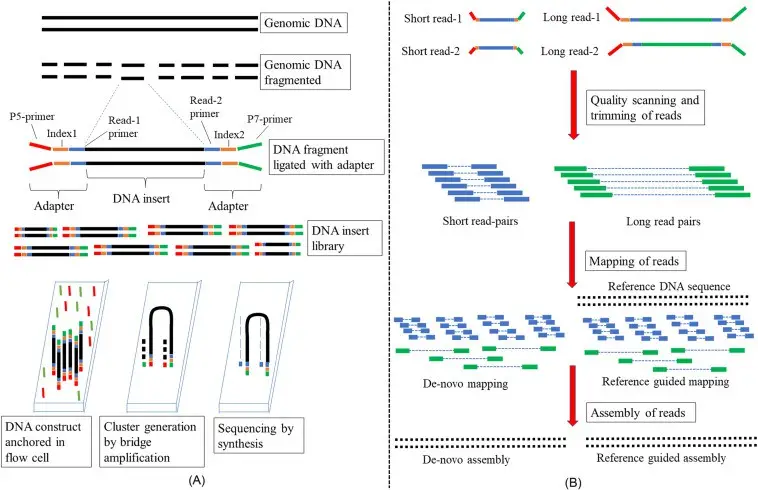

- Second-Generation Sequencing, also known as Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), operates primarily through two key processes: clonal amplification and sequencing by synthesis. Initially, DNA fragments are affixed to a solid surface, such as a glass slide, where they undergo clonal amplification. This process, known as bridge amplification, produces clusters of identical DNA fragments. Following this, sequencing by synthesis is performed, where fluorescently labeled nucleotides are sequentially incorporated into the growing DNA strands. Each nucleotide incorporation emits a unique fluorescent signal, which is detected by a camera. The sequence of the DNA is determined by the order and intensity of these signals, as the system cycles through nucleotide incorporation, washing, and imaging.

- Third-Generation Sequencing includes technologies that deviate from the clonal amplification step. Single Molecule Sequencing methods, such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) SMRT sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT), enable the direct sequencing of individual DNA molecules. In PacBio SMRT sequencing, zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) are used to observe nucleotide incorporation in real-time. A single DNA molecule is sequenced as it interacts with a polymerase enzyme, with fluorescent signals from incorporated nucleotides continuously recorded. This method provides long read lengths and high accuracy. On the other hand, Oxford Nanopore Technology sequences DNA by passing it through a nanopore and measuring changes in electrical current caused by individual nucleotides. This approach yields very long reads, sometimes up to 4 megabases, and allows for real-time sequencing.

- Overall, HTS technologies have significantly advanced genomic research by facilitating high-speed, high-throughput sequencing. These methods have broad applications across genomics, transcriptomics, and metagenomics, providing deep insights into genetic material and its functions.[ref – 1,2,3]

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies have revolutionized genomic research by enabling rapid and detailed analysis of genetic material. The principal HTS technologies can be categorized into next-generation sequencing (NGS) and third-generation sequencing. Each of these technologies has distinct methodologies, advantages, and limitations. Here, we provide an overview of four major HTS technologies: Illumina sequencing, ThermoFisher’s Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, and Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT).

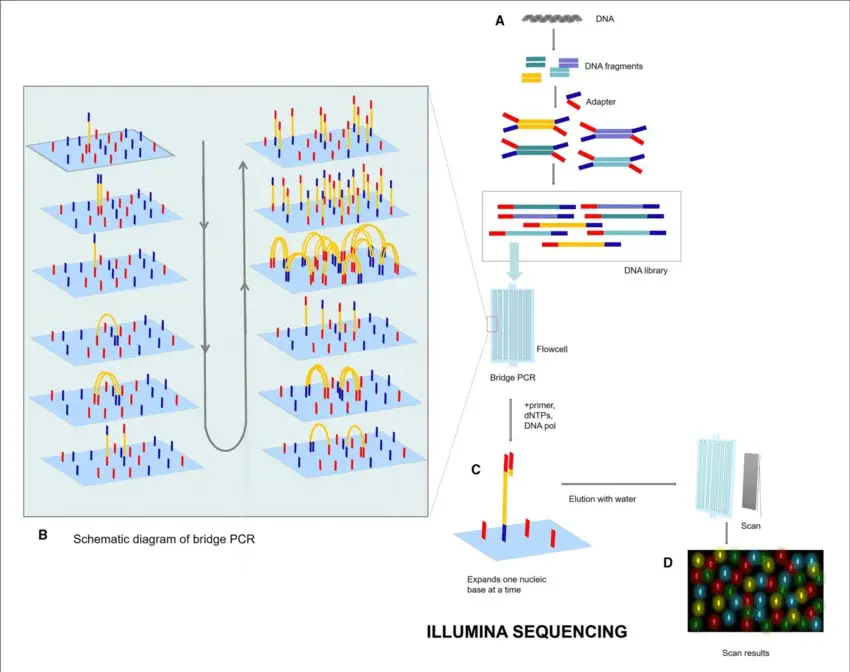

1. Illumina Sequencing

- Principle: Illumina sequencing, a dominant technology in the HTS market, employs clonal amplification and produces short reads ranging from 100 to 400 base pairs. The process begins with DNA fragments being ligated to adaptors on a glass slide. These fragments undergo bridge amplification, creating clusters of identical DNA fragments.

- Sequencing Method: The sequencing process uses cyclic reversible termination chemistry, where nucleotides are incorporated one at a time. Each nucleotide is fluorescently labeled, allowing for nucleotide detection through imaging after each incorporation step. This is followed by cleavage of the fluorescent tag and a repeat of the incorporation process.

- Advantages: Illumina sequencing is highly cost-effective per base, provides high throughput, and benefits from well-established protocols and a large user base.

- Limitations: The primary drawbacks include shorter read lengths compared to other technologies, typically between 150 and 300 base pairs, and reduced accuracy for longer reads and GC-rich genomic regions.

2. ThermoFisher’s Ion Torrent

- Principle: Ion Torrent sequencing is based on semiconductor technology, distinguishing it from optical-based methods. It uses clonal amplification similar to Roche/454 pyrosequencing but measures pH changes rather than light production to detect nucleotide incorporation.

- Sequencing Method: The sequencing-by-synthesis approach involves detecting pH changes caused by the release of hydrogen ions during nucleotide incorporation. These pH changes are converted into voltage signals that correspond to nucleotide sequences.

- Advantages: This technology offers rapid sequencing times, with results available in a matter of hours. It also has a lower cost per base compared to other technologies.

- Limitations: Ion Torrent sequencing typically generates shorter reads around 200 base pairs and has limited accuracy compared to other technologies.

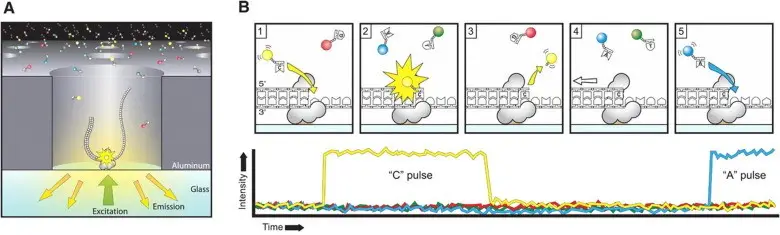

3. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) SMRT Sequencing

- Principle: SMRT sequencing utilizes single-molecule real-time technology to produce longer reads, often exceeding 10 kilobases. DNA molecules are prepared with hairpin adapters that enable circularization and repeated sequencing of the same molecule.

- Sequencing Method: The technology involves observing nucleotide incorporation in real-time using zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs). Each ZMW contains a single polymerase enzyme, and fluorescently labeled nucleotides are incorporated sequentially while recording fluorescent signals.

- Advantages: PacBio offers the longest read lengths and high accuracy with error rates below 1%, making it suitable for de novo genome assembly and detailed epigenetic studies.

- Limitations: The technology is relatively expensive, with a high cost per base, and has lower throughput compared to other sequencing methods.

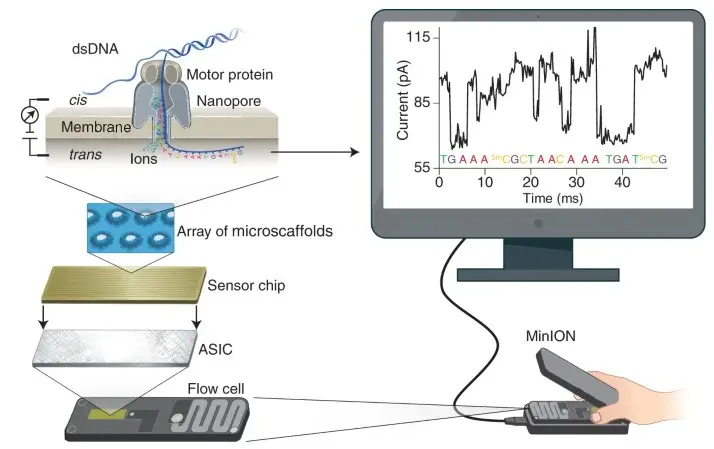

4. Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT)

- Principle: ONT’s sequencing technology involves passing DNA or nucleotides through nanopores—tiny protein channels embedded in a membrane. This method measures changes in electrical current caused by nucleotide passage through the nanopore.

- Sequencing Method: DNA sequencing with ONT involves fragmenting DNA, attaching adapters, and using a proprietary motor enzyme to thread DNA through the nanopore. The current changes are used to identify individual nucleotides based on their unique electrical signatures.

- Advantages: Oxford Nanopore technology provides long read lengths, often over 10 kilobases, and is notable for its portability and flexibility. The technology also allows for real-time sequencing and data analysis.

- Limitations: The cost per base is relatively high, though lower than PacBio. Additionally, ONT generally has lower throughput and higher variability in accuracy, especially for shorter read lengths.Pros and cons of four major HTS technologies[ref – 2]

Pros and cons of four major HTS technologies

| Technology | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Sequencing | – Widespread Use: Extensive adoption, large user base, well-established protocols. – High Throughput: Generates substantial data in a single run. – Cost-Effective: Low cost per base, economically advantageous. | – Short Read Lengths: Short reads (150-300 bp) may struggle with complex regions. – Accuracy Limitations: Reduced accuracy for longer reads and high GC content. |

| ThermoFisher’s Ion Torrent | – High Throughput: Large number of reads per run, detailed analysis. – Cost Efficiency: Lower cost per base relative to some technologies. – Rapid Sequencing: Fast results, typically within hours. | – Shorter Read Lengths: Similar short read lengths (around 200 bp) may affect resolution. – Accuracy Issues: Generally lower accuracy compared to other methods. |

| Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) SMRT Sequencing | – Long Read Lengths: Very long reads (>10 kb), beneficial for de novo assembly. – High Accuracy: Error rates typically below 1%, suitable for detailed applications. | – High Cost: Expensive with a higher cost per base. – Lower Throughput: Fewer reads per run compared to other technologies. |

| Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) | – Long Read Lengths: Long reads (>10 kb), good for complex genomes and structural variations. – Real-Time Sequencing: Immediate insights and rapid progress. – Portability and Flexibility: Portable sequencers, suitable for diverse environments. | – High Cost: Relatively high cost per base, though more affordable than PacBio. – Lower Throughput: Fewer reads per run, limiting coverage. – Accuracy Variability: Variable accuracy with higher error rates for shorter reads. |

Differences of high-throughput sequencing technologies

Here’s an enhanced version of the comparative table with more descriptive information:

| Feature | Illumina Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Sequencing | Pacific Biosciences Sequencing | Ion Torrent Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS), where DNA fragments are sequenced through the incorporation of fluorescently labeled nucleotides, detected by a camera. | Based on nanopore technology, where DNA molecules pass through nanopores, and nucleotide sequences are inferred from changes in ionic current. | Employs Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, where DNA sequencing is observed by detecting the addition of nucleotides to a single DNA molecule in real-time. | Utilizes semiconductor-based sequencing, where changes in pH during nucleotide incorporation are detected and converted into DNA sequences. |

| Read Length | Provides short to medium read lengths, typically ranging from 75 to 300 base pairs. | Capable of generating long reads, often spanning entire genes or genomes, with lengths up to several megabases. | Offers long reads that can cover entire genes or large genomic regions, often in the range of several kilobases. | Generally produces short to medium reads, typically ranging from 200 to 400 base pairs. |

| Accuracy | High accuracy, attributed to the sequencing-by-synthesis technology and error-correction algorithms, making it reliable for precise genomic analyses. | Accuracy can be variable, often influenced by factors such as DNA quality and sequencing conditions; newer technologies are improving consistency. | High accuracy, supported by advanced error-correction methods; generally provides reliable sequence data for complex genomes. | Provides moderate to high accuracy; less consistent compared to Illumina but sufficient for many applications. |

| Throughput | High throughput, suitable for large-scale sequencing projects such as whole-genome sequencing and RNA sequencing, allowing the analysis of millions of reads in parallel. | Moderate to high throughput, capable of handling a range of sequencing tasks from small to large scale, depending on the device used. | Moderate throughput, appropriate for specific applications like genome assembly and metagenomics, typically handling a lower volume of sequences compared to Illumina. | Moderate to high throughput, providing sufficient capacity for various sequencing tasks including targeted sequencing and mutation profiling. |

| Fragmentation Requirement | Requires DNA fragmentation before sequencing, which involves breaking the DNA into smaller pieces to fit into the sequencing platform. | Does not require DNA fragmentation, allowing for the sequencing of intact DNA molecules, which can be beneficial for certain applications like structural variant detection. | Does not require DNA fragmentation, which enables the sequencing of long DNA molecules, advantageous for generating long reads and assembling genomes. | Requires DNA fragmentation before sequencing, similar to Illumina, to ensure DNA fits into the sequencing system. |

| Real-Time Sequencing | Does not offer real-time sequencing capabilities; sequencing data is generated in batches and analyzed after the completion of the run. | Provides real-time sequencing, allowing for immediate data acquisition and analysis during the sequencing process, useful for on-the-spot applications. | Facilitates real-time sequencing, enabling immediate feedback and analysis of sequencing data as it is generated. | Capable of real-time sequencing, allowing for concurrent data acquisition and analysis during the sequencing process. |

| Portability | Limited portability; typically requires large, stationary equipment and infrastructure for operation, not suitable for fieldwork. | Highly portable; devices like the MinION can be used in diverse settings, including field environments, making it versatile for various applications. | Equipment is generally not portable; requires laboratory-based systems that are large and specialized. | Limited portability; requires specific infrastructure and equipment, making it less suitable for mobile or field-based work. |

| Applications | Commonly used for whole-genome sequencing, exome sequencing, and RNA sequencing, providing detailed insights into genetic variations and expression profiles. | Ideal for de novo genome assembly, structural variant detection, and real-time pathogen surveillance, offering flexibility and long-read capabilities. | Well-suited for genome assembly, metagenomics, and transcriptomics, with strengths in generating long reads and comprehensive analyses. | Primarily used for targeted amplicon sequencing, microbial genomics, and cancer mutation profiling, focusing on specific genetic regions or mutations. |

Steps of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS)

The process of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS) involves a series of methodical steps, which can vary depending on the sequencing technology employed. Here is a detailed overview of these steps:

- Sample Preparation

- DNA/RNA Extraction: The initial step involves isolating DNA or RNA from the biological sample, ensuring that the nucleic acids are of high quality and suitable for sequencing.

- Fragmentation: The extracted nucleic acids are fragmented into smaller pieces, generally ranging from 100 to several thousand base pairs. This fragmentation is necessary to facilitate the sequencing process.

- Adapter Ligation: Short DNA sequences, known as adapters, are ligated to both ends of the fragmented nucleic acids. These adapters are essential for the subsequent binding of fragments to the sequencing platform and for amplification.

- Library Preparation

- Size Selection: The DNA fragments are often size-selected to ensure uniformity within the library. This step helps in improving the overall sequencing quality by eliminating fragments that are too short or too long.

- Amplification (for Second-Generation Sequencing): The prepared library undergoes amplification using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This process creates multiple copies of each fragment, increasing the amount of DNA available for sequencing.

- Sequencing

- Loading the Library: The prepared library is loaded onto the sequencing platform, such as a flow cell in Illumina sequencing or a nanopore in Oxford Nanopore Technology.

- Sequencing by Synthesis (Second-Generation):

- Nucleotides are added one at a time to the growing DNA strands. Each nucleotide addition emits a specific fluorescent signal.

- A camera captures these fluorescent signals after each incorporation step, which allows for the determination of the DNA sequence based on the order of emitted signals.

- Single-Molecule Sequencing (Third-Generation):

- PacBio SMRT Sequencing: Uses zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) to monitor nucleotide incorporation in real-time. Fluorescent signals from each nucleotide addition are recorded as a single DNA molecule passes through a polymerase.

- Oxford Nanopore Technology: Measures changes in electrical current as DNA or nucleotides pass through a nanopore, allowing for direct reading of the sequence.

- Data Acquisition

- The sequencing machine generates raw data, typically in the form of images or electrical signals. These represent the nucleotide sequence and are essential for further processing.

- Data Processing

- Base Calling: The raw data is converted into nucleotide sequences through a process known as base calling.

- Quality Control: Sequences are assessed for quality, and any low-quality reads are filtered out to ensure reliable results.

- Alignment and Assembly: The sequences are aligned against a reference genome or assembled de novo. Computational algorithms are used to handle the extensive data and reconstruct the original DNA sequence.

- Data Analysis

- The aligned sequences are analyzed to identify genetic variants, study gene expression, or explore microbial diversity. This analysis provides insights into various biological questions and research objectives.

- Interpretation and Reporting

- The final step involves interpreting the results in the context of the biological questions being addressed. Findings are reported through visualizations, statistical analyses, and comparisons to existing databases.[ref – 2]

(A) Wet lab steps and (B) dry lab steps. (Maloyjo Joyraj Bhattacharjee, Basant K. Tiwary, in Biotechnology in Healthcare, 2022)

Advantages of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS)

The primary advantages of HTS include:

- Precision and Accuracy

- Impeccable Quality: HTS provides sequencing data with high precision and accuracy, surpassing the capabilities of conventional methods. This high level of detail ensures that researchers obtain reliable and reproducible results.

- Error Reduction: The technology minimizes sequencing errors, which is crucial for applications such as variant calling and mutation detection. Accurate detection of genetic alterations is essential for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies.

- Scalability

- Large-Scale Sequencing: HTS supports the sequencing of large volumes of DNA or RNA in a single experiment. This feature is essential for comprehensive projects, such as whole-genome sequencing or in-depth transcriptomic studies using RNA-seq.

- High Sample Throughput: By handling multiple samples simultaneously, HTS allows for extensive analysis of genetic diversity, gene expression patterns, and regulatory networks across various biological systems.

- Speed and Efficiency

- Rapid Data Generation: HTS can produce vast quantities of sequencing data much faster than traditional methods. This speed is beneficial for accelerating experiments and generating timely scientific insights.

- Clinical Diagnostics: In clinical settings, the efficiency of HTS facilitates quick mutation detection, which is vital for prompt diagnosis and treatment of genetic disorders.

- Versatility

- Wide Application Range: HTS technologies are highly versatile, applicable to a broad spectrum of analyses, from whole-genome and exome sequencing to ChIP-seq and RNA-seq studies.

- Broad Impact: This versatility supports advancements across multiple fields, including cancer genomics, developmental biology, and microbiology, thereby enhancing our understanding of molecular biology.

- Cost-Effectiveness

- Economical for Large Projects: HTS is more cost-effective for large-scale projects due to its ability to process numerous samples in a single run. This lowers the overall cost per sample compared to traditional sequencing methods.

- Comprehensive Data Generation

- Detailed Information: HTS produces extensive amounts of data in each sequencing run, providing detailed insights necessary for thorough genetic analysis. This capacity is advantageous for in-depth studies requiring comprehensive data coverage.[ref – 4,5,6,7,8]

Limitations of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS)

High Throughput Sequencing (HTS), while offering numerous advantages, also presents several limitations that can impact its effectiveness and utility. These limitations are critical to consider for researchers and practitioners using HTS technologies. The primary limitations of HTS include:

- Data Complexity and Volume

- Large Data Sets: HTS produces extensive amounts of data, which poses challenges in terms of storage, management, and analysis. Handling this data necessitates substantial computational resources and specialized bioinformatics expertise.

- Data Interpretation: The interpretation of HTS data can be complex. Distinguishing between biologically significant variations and artifacts introduced during sequencing requires sophisticated analytical approaches.

- Error Rates

- Sequencing Errors: Different HTS technologies exhibit varying error profiles. For instance, short-read sequencing technologies, such as those from Illumina, may have higher rates of substitution errors, while long-read sequencing technologies, like those from PacBio, may be prone to errors in insertions and deletions. These discrepancies can affect the accuracy of variant calling and genome assembly.

- Homopolymer Regions: Sequencing errors are frequently encountered in homopolymer regions, which consist of repeated nucleotides. This complicates accurate sequencing and can lead to challenges in determining the correct sequence in these areas.

- Cost Considerations

- Initial Setup Costs: Despite the reduction in per-sample costs, the initial investment required for HTS equipment and infrastructure remains considerable. This can be a barrier for smaller laboratories or institutions with limited budgets.

- Ongoing Operational Costs: The continuous expenses associated with reagents, maintenance, and data storage can accumulate, presenting a financial challenge for long-term or large-scale projects.

- Biases in Sequencing

- Library Preparation Bias: The library preparation process can introduce biases, such as the preferential amplification of certain fragments. This can lead to an inaccurate representation of the original sample.

- PCR Bias: During the amplification process, some sequences may be overrepresented or underrepresented, which can result in skewed data and affect the reliability of the final results.

- Limitations in Resolution

- Short Reads: Short-read sequencing technologies may lack the resolution needed to accurately characterize complex genomic regions, structural variants, or repetitive sequences.

- Assembly Challenges: De novo assembly of genomes, particularly those with high levels of heterozygosity or repetitive elements, can be computationally demanding and may result in incomplete or inaccurate assemblies.

- Technical Limitations

- Sample Quality: The quality of the input DNA or RNA significantly influences the outcome of HTS. Samples that are degraded or contaminated can lead to poor-quality data.

- Single-Cell Sequencing: Although single-cell sequencing technologies offer insights into cellular heterogeneity, they face limitations such as low throughput, high costs, and difficulties in capturing rare cell types.

- Ethical and Privacy Concerns

- Data Privacy: The use of genomic data raises ethical issues related to privacy and consent, especially in clinical and personal genomics contexts.

- Potential for Misuse: There are concerns regarding the misuse of genetic information, including potential discrimination in insurance and employment settings.

- Regulatory Challenges

- Standardization: The rapid advancement of HTS technologies has outpaced the development of standardized protocols and guidelines. This lack of standardization can lead to variability in results across different laboratories and studies.[ref – 1,2,4,5,6,]

Applications of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS)

Below is an overview of how HTS is utilized across various fields:

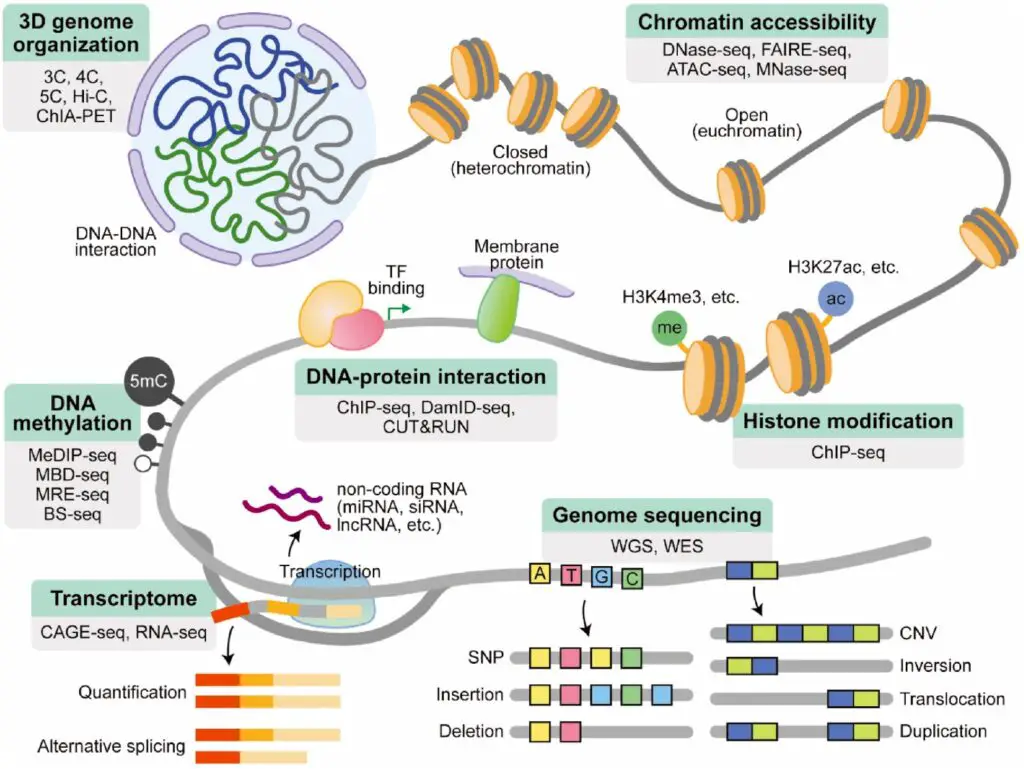

- Genome Sequencing

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): HTS enables the comprehensive sequencing of entire genomes, allowing researchers to investigate genetic variations, evolutionary relationships, and population genetics on a grand scale.

- Targeted Sequencing: This approach focuses on specific genomic regions of interest, which helps in identifying mutations linked to particular diseases.

- Transcriptome Analysis

- RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq): HTS provides a detailed analysis of the RNA transcripts present in a cell or tissue. This includes profiling gene expression levels, detecting alternative splicing events, and identifying non-coding RNAs. This method is crucial for understanding cellular mechanisms and gene regulation.

- Epigenomics

- DNA Methylation Analysis: HTS techniques are used to map DNA methylation patterns across the genome. This information is vital for studying gene regulation and epigenetic modifications.

- Histone Modification Studies: Methods like Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) allow the examination of histone modifications, which influence gene expression and chromatin structure.

- Metagenomics

- Microbiome Studies: HTS allows for the detailed analysis of microbial communities in various environments, such as the human gut or soil, by sequencing the collective genomes of microorganisms.

- Pathogen Detection: HTS is used to identify and characterize pathogens in clinical samples, aiding in disease diagnosis and monitoring outbreaks.

- Cancer Genomics

- Tumor Profiling: HTS helps in identifying genetic mutations, copy number variations, and structural changes in cancer genomes, which can guide personalized treatment strategies.

- Liquid Biopsies: By analyzing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood samples, HTS offers insights into tumor dynamics and response to therapy.

- Agrigenomics

- Crop Improvement: HTS is applied in plant genomics to identify genetic traits associated with yield, disease resistance, and stress tolerance, leading to the development of better crop varieties.

- Animal Breeding: In livestock, HTS enhances breeding programs by identifying genetic markers for desirable traits.

- Evolutionary Biology

- Phylogenetics: HTS is used to reconstruct evolutionary relationships among species by comparing genomic sequences, providing insights into evolutionary history and species divergence.

- Synthetic Biology

- Gene Synthesis and Engineering: HTS supports the design and construction of synthetic genes and biological systems, facilitating the development of novel organisms and pathways.

- Clinical Applications

- Personalized Medicine: HTS helps identify genetic variants that affect drug responses, enabling tailored treatment plans based on an individual’s genetic profile.

- Genetic Disorder Diagnosis: HTS is utilized to diagnose genetic disorders by detecting pathogenic variants in patient genomes.

- Forensic Science

- DNA Profiling: HTS is used in forensic investigations to analyze DNA samples from crime scenes, providing high-resolution profiles for identification purposes.[ref -2,4]

FAQ

[display_qa ids=”58993,58994,58995,58996,58997,58998,58999,59000,59001,59002,59003,59004,59005,59006,59007,59008,58991,58990,58989,58988″]

- Slatko, B. E., Gardner, A. F., & Ausubel, F. M. (2018). Overview of Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, 122(1), e59. doi:10.1002/cpmb.59

- Lee Jun-Yeong. The Principles and Applications of High-Throughput Sequencing Technologies. Dev. Reprod. 2023;27(1):9-24.

https://doi.org/10.12717/DR.2023.27.1.9 - Churko JM, Mantalas GL, Snyder MP, Wu JC. Overview of high throughput sequencing technologies to elucidate molecular pathways in cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2013 Jun 7;112(12):1613-23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300939. PMID: 23743227; PMCID: PMC3831009.

- https://www.cd-genomics.com/resource-comprehensive-overview-high-throughput-sequencing.html#guide1

- https://www.illumina.com/techniques/sequencing/high-throughput-sequencing.html

- https://geneticeducation.co.in/high-throughput-sequencing/

- https://www.iit.edu/ifsh/capabilities/high-throughput-sequencing

- https://www.news-medical.net/life-sciences/High-throughput-DNA-Sequencing-Techniques.aspx

- https://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/fulltext/S1097-2765(15)00340-8?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS1097276515003408%3Fshowall%3Dtrue