Hepatitis A is a liver inflammation brought on by the hepatitis A virus (HAV). Primarily, the virus is transmitted when an uninfected (and unvaccinated) individual consumes food or water contaminated with the faeces of an infected individual. The disease is strongly linked to unclean water or food, inadequate sanitation, poor personal hygiene, and oral-anogenital contact.

Hepatitis A, unlike hepatitis B and C, does not produce chronic liver disease, but it can induce incapacitating symptoms and, in rare cases, fulminant hepatitis, which is frequently fatal. WHO estimates that 7134 people died from hepatitis A in 2016, accounting for 0.5% of viral hepatitis-related mortality.

Worldwide, hepatitis A occurs infrequently and in epidemics, with a propensity for cyclical recurrence. Epidemics caused by tainted food or water can erupt explosively, such as the pandemic that impacted around 300,000 people in Shanghai in 1988. (1). They can also be perpetuated via person-to-person transmission, impacting communities for months. Hepatitis A viruses persist in the environment and are resistant to food production methods that are often employed to inactivate or regulate bacterial diseases.

- The liver infection known as hepatitis A can cause mild to severe sickness.

- The hepatitis A virus (HAV) is transmitted by the consumption of contaminated food and drink, as well as through direct contact with an infectious person.

- Almost everyone who contracts hepatitis A recovers totally and develops permanent immunity. However, a very small percentage of those infected with hepatitis A may develop fulminant hepatitis and die as a result.

- The risk of hepatitis A infection is linked to a lack of potable water, as well as to poor sanitation and hygiene (such as contaminated and dirty hands).

- There is a safe and effective vaccine to prevent hepatitis A.

Geographical distribution of Hepatitis A Virus

High, intermediate, or low levels of hepatitis A virus infection can be attributed to distinct geographical distribution zones. However, infection does not always indicate sickness because small children who are infected do not exhibit visible symptoms.

In low- and middle-income nations with inadequate sanitary conditions and hygienic practises, hepatitis A infection is frequent, and the majority of children (90%) have been infected with the virus before the age of 10 years, typically without symptoms (2). In countries with high incomes and strong sanitation and hygiene, infection rates are low. Disease may occur among adolescents and adults in high-risk groups, such as people who inject drugs (PWID), men who have sex with men (MSM), travellers to highly endemic regions, and members of isolated populations, such as restricted religious groups. In the United States of America, major outbreaks among homeless individuals have been observed. In middle-income nations and locations with varying sanitary standards, young children frequently avoid infection and enter adulthood without immunity.

Taxonomy of Hepatitis A Virus

- Hepatitis A virus belongs to the order Picornavirales, family Picornaviridae, and genus Hepatovirus. Humans and other vertebrates are natural hosts for parasites.

- There are nine known Hepatovirus species.

- These organisms are capable of infecting bats, rodents, hedgehogs, and shrews. A phylogenetic analysis reveals that Hepatitis A originated in rodents.

- A hepatovirus B (Phopivirus) member virus has been isolated from a seal.

- This virus and Hepatovirus A shared a common ancestor approximately 1800 years ago.

- Marmota himalayana hepatovirus, a new hepatovirus, has been discovered from the woodchuck Marmota himalayana.

- This virus appears to have had a common ancestor with viruses that infect primates approximately one thousand years ago.

Structure of Hepatitis A Virus

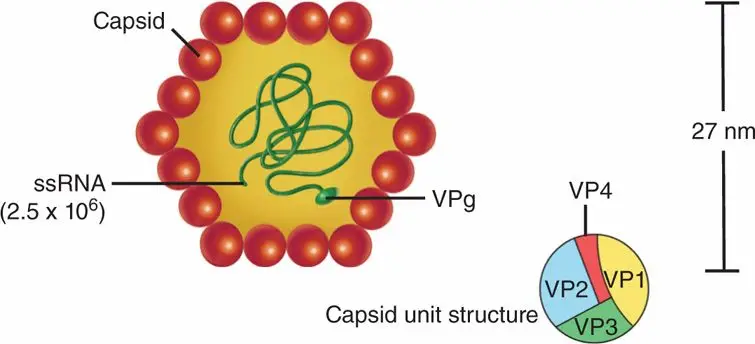

- The infectious spherical virion is a non-encapsulated particle with a diameter of around 27 nanometers. The viral RNA genome is embodied by the icosahedral capsid, which contains 60 copies of each of the three main proteins, VP1 (also known as 1D), VP2 (1B), and VP3 (1C).

- The integration of the tiny protein VP4 (1A) into the capsid is unknown. The mature HAV virion appears to have a different structure than that of other picornaviruses, as the canyon surrounding the fivefold symmetry axis, a characteristic that reflects the viral attachment point to cellular receptors, is conspicuously absent.

- The buoyant density of the HAV particle in CsCl is approximately 1.33 g cm-3, and its sedimentation coefficient is approximately 160S. In faeces, empty capsids have a sedimentation constant of approximately 70S.

- HAV is highly resistant to acid (pH 1.0 for two hours at ambient temperature) and thermal inactivation (60 C for 1 h).

Genome Organization of Hepatitis A Virus

- The linear, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome of HAV is 7500 nt in length and is not capped but covalently attached to the 2.5 kDa viral protein 3B via a tyrosine-O4 -phosphodiester bond (also known as VPg;).

- It contains a structurally complex 50 nontranslated region (NTR) of 740 bases, a single open reading frame encoding a polyprotein (about 250 kDa; 2230 amino acids), and a 30 NTR of 60 bases that culminates with a poly(A) tail of approximately 60 nt.

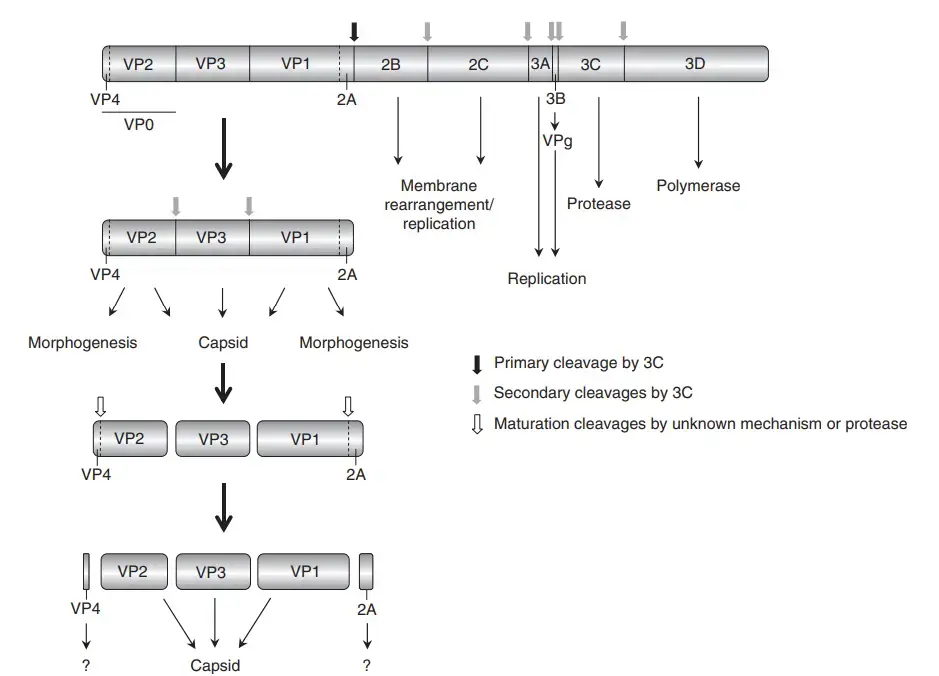

- The N-terminal third of the polyprotein consists of the capsid proteins and those with functions during virion assembly (VP4, VP2, VP3, VP1, also known as the P1 region, and 2A), while the remainder consists of a series of proteins required for RNA replication (2B, 2C, and 3A to 3D).

Transmission of Hepatitis A Virus

Primarily, the hepatitis A virus is transmitted by the faecal-oral route, which occurs when an uninfected person consumes food or water contaminated with the faeces of an infected person. This may occur in households when an infected person prepares food for family members with unclean hands. Infrequent waterborne epidemics are typically linked to sewage-contaminated or improperly cleaned water.

The virus can also be transferred through close physical contact (such as oral-anal sex) with an infected person, although casual contact between individuals does not spread the virus.

Replication of Hepatitis A Virus

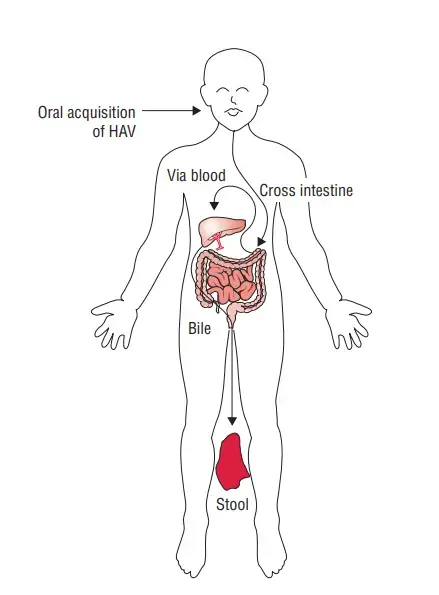

- HAV is primarily transmitted by consuming fecally contaminated food or drink.

- After entering the colon, HAV is believed to be absorbed into the bloodstream and transported to the liver via the portal system.

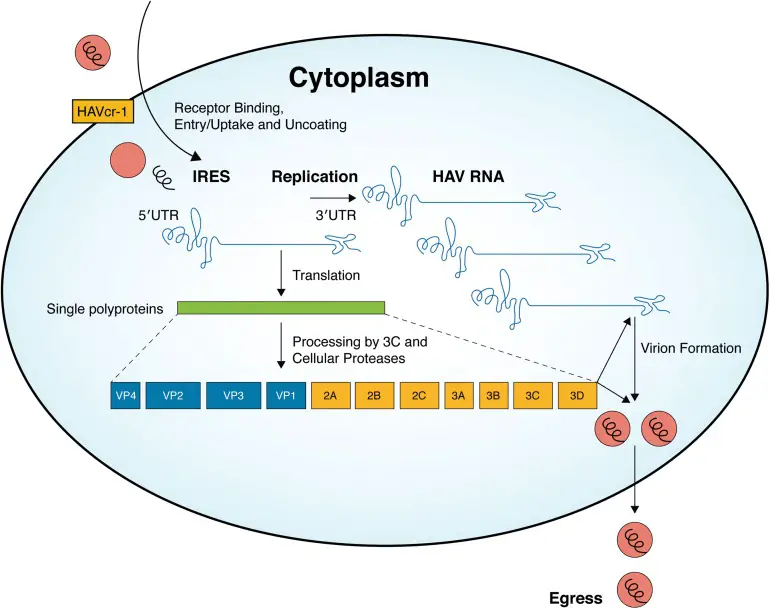

- Attachment of the virus to receptors on the host cell (HAV cr-1) mediates endocytosis of the virus into the host cell, potentially via clathrin-dependent endocytosis.

- Upon endosomal acidification, the capsid undergoes a structural shift and releases VP4, which forms a pore in the endosomal membrane of the host cell, allowing viral genomic RNA to enter the cytoplasm.

- VPg is extracted from viral RNA, which is then translated into a processed polyproten.

- The IRES permits direct polyprotein translation.

- Synthesis of a ds RNA genome from genomic ssRNA(+).

- The dsRNA genome is transcribed, resulting in the production of viral mRNAs and new ssRNA(+) genomes.

- It is hypothesised that new genomic RNA is bundled into preassembled procapsids.

- During cell lysis, virus is released.

Pathogenesis of Hepatitis A Virus

Hepatitis A virus infection is spread by the fecal–oral route and is associated with hepatocellular damage; however, the pathophysiology of HAV infection is not well known.

Pathogenesis of hepatitis A virus infection

The virus appears to replicate initially in the digestive tract before spreading to the liver. In the liver, viruses infect hepatocytes and cause harm to these cells. However, the mechanism via which HAV has a cytopathic effect is unknown. Cytotoxic T cells appear to produce damage to hepatocytes; hence, once the infection has been eliminated, the damage to the cells is repaired and there is no chronic infection. Hepatocytes typically exhibit mononuclear infiltration, ballooning, degeneration, and acidophilic (Councilman-like) structures. Histologically, HAV-induced liver disease cannot be separated from that produced by other hepatitis viruses.

Host immunity

The majority of host immunity is mediated by circulating antibodies. Acute infection is defined by the development of IgM anti-HAV, which is evident with the onset of jaundice. The IgM antibody, however, disappears few months following jaundice. IgG antibodies arise one to three weeks following IgM antibodies. It appears that IgG antibody confers lifelong protection against recurrent HAV infection.

Clinical Manifestations of Hepatitis A Virus

Acute hepatitis A is caused by Hepatitis A virus, and its symptoms are comparable to those of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

Acute hepatitis A

- The incubation time for HAV ranges from 15 to 45 days, averaging 4 weeks. It is rather brief compared to the lengthy HBV infection incubation period.

- The most common symptoms and indicators of the condition include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, fever, hepatomegaly, jaundice, anorexia, and rash.

- Additionally, the illness is accompanied with dark urine, pale stools, and increased serum transaminase levels. Infection with the Hepatitis A virus is often a mild, self-limiting condition that cures spontaneously in 2–4 weeks.

- Infection with Hepatitis A virus confers lifetime protection to HAV. With HAV infection, chronic hepatitis or chronic carrier condition are not observed. Hepatitis A virus also never causes hepatocellular cancer.

- Acute hepatitis A is significantly more severe and fatal in adults than in children. Unknown is the specific cause behind this. Infrequent consequences include acute liver failure and cholestatic hepatitis. The death rate attributable to HAV is extremely low, at roughly 0.01%.

Laboratory Diagnosis of hepatitis A

There are several laboratory tests that can be used to diagnose hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection. These tests can detect the presence of HAV in the blood, as well as measure the amount of virus present (viral load) and determine the genotype (strain) of the virus. Here are some common laboratory tests used to diagnose HAV infection:

- HAV Antibody Test: This test looks for antibodies to HAV in the blood. Antibodies are proteins produced by the immune system in response to an infection. If the test is positive, it means that the person has been infected with HAV at some point in their life, although it does not necessarily mean that they are currently infected.

- HAV RNA Test: This test looks for the genetic material (RNA) of the HAV virus in the blood. If the test is positive, it means that the person is currently infected with HAV.

- HAV Genotype Test: This test determines the strain of the HAV virus that is present in the blood. There are several different genotypes of HAV, and the specific genotype can affect how the virus is treated.

- HAV Viral Load Test: This test measures the amount of HAV virus in the blood. A high viral load may indicate a more severe infection and a greater risk of liver damage.

It’s important to note that these tests are not always 100% accurate and may give false-positive or false-negative results. If you think you may have been exposed to HAV or are experiencing symptoms of hepatitis, it’s important to talk to a healthcare provider to determine the best course of action.

Vaccination of Hepatitis A Virus

Hepatitis A is a viral infection that is caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV). A vaccine is available to prevent hepatitis A infection. The hepatitis A vaccine is usually given as a series of two injections, with the second injection given 6 to 18 months after the first.

The hepatitis A vaccine is highly effective at preventing HAV infection. It is recommended for all children at age 1, as well as for people who are at increased risk of contracting HAV, such as travelers to countries with high rates of HAV, men who have sex with men, and people with chronic liver disease.

Prevention and control of Hepatitis A Virus

The most effective means of combating hepatitis A are improved sanitation, food safety, and vaccination.

Reduce the transmission of hepatitis A through:

- appropriate supplies of safe drinking water;

- effective sewage disposal within communities;

- and personal hygiene practises such as routine handwashing before meals and after using the restroom.

Internationally, several inactivated injectable hepatitis A vaccinations are available. All offer equivalent protection against the infection and have comparable adverse effects. No approved vaccine is intended for infants less than one year. A live attenuated vaccine is also available in China.

FAQ

What is Hepatitis A virus?

Hepatitis A virus is a highly contagious virus that can cause inflammation of the liver. It is primarily transmitted through the consumption of contaminated food or water.

How is Hepatitis A virus transmitted?

Hepatitis A virus is transmitted through the fecal-oral route, typically through the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the virus. It can also be transmitted through close personal contact with an infected person or through exposure to contaminated objects or surfaces.

What are the symptoms of Hepatitis A virus infection?

Symptoms of Hepatitis A virus infection can range from mild to severe and may include fever, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and jaundice.

Is there a vaccine available for Hepatitis A virus?

Yes, there is a vaccine available for Hepatitis A virus. The vaccine is recommended for all children and for adults who are at increased risk of infection.

How is Hepatitis A virus diagnosed?

Hepatitis A virus is diagnosed through a blood test that detects antibodies to the virus.

What is the treatment for Hepatitis A virus infection?

There is no specific treatment for Hepatitis A virus infection. Treatment typically involves supportive care, such as rest and hydration, to help manage symptoms and prevent complications.

Can Hepatitis A virus infection be prevented?

Yes, Hepatitis A virus infection can be prevented through good hygiene practices, such as washing hands regularly and thoroughly, avoiding contaminated food and water, and getting vaccinated.

Who is at risk of Hepatitis A virus infection?

Anyone can be at risk of Hepatitis A virus infection, but certain groups are at increased risk, including people who travel to countries with high rates of Hepatitis A virus, men who have sex with men, people who use illegal drugs, and people who work with or are in close contact with infected individuals.

Is Hepatitis A virus infection contagious?

Yes, Hepatitis A virus infection is highly contagious and can be transmitted through close personal contact with an infected person or through exposure to contaminated objects or surfaces.

How long does it take to recover from Hepatitis A virus infection?

Most people recover fully from Hepatitis A virus infection within a few weeks to several months. In rare cases, the infection can lead to more severe liver disease and complications.

References

- Dotzauer, A. (2008). Hepatitis A Virus. Encyclopedia of Virology, 343–350. doi:10.1016/b978-012374410-4.00412-x

- https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/book/3-s2.0-B9780323482554001740

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-a

- https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/index.htm

- https://www.fda.gov/food/foodborne-pathogens/hepatitis-virus-hav