DNA recombination is the process in which the genetic material (DNA) is exchanged between two DNA molecules. It is the natural method for reshuffling of genes, and it is observed in most living organisms. It is the process where the DNA strand is broken and then repaired, and new combination of alleles is formed.

It is the process that help in maintaining the stability of genome by repairing different types of DNA damages (like double-strand break). This process occurs when the cells undergo meiotic division also, where the paternal and maternal chromosomes exchange their genetic segments. These are important for producing genetic variation in sexually reproducing organism.

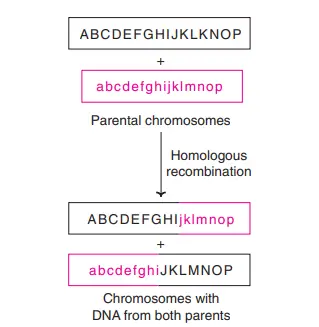

Among the important type, homologous recombination is the process in which the exchange occurs between two DNA molecules that are similar in their nucleotide sequences.

In genetic engineering, recombination is referred to as the artificial joining of DNA fragments obtained from different sources forming recombinant DNA (rDNA). It is used in producing different biological products like therapeutic proteins and vaccines.

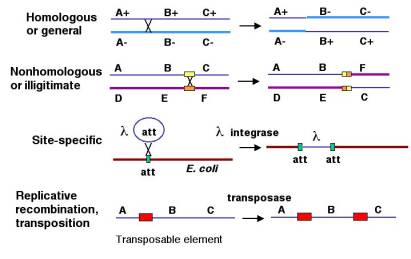

Types of DNA Recombination

DNA recombination can be divided into different types depending on the nature of DNA sequence involved and the condition in which the process occurs. It is the method used by cells to repair DNA damage and to create new genetic arrangement.

1. Homologous Recombination (HR)

It is the process where the exchange of DNA occurs between two similar or identical DNA molecules. It is used in accurate repair of double-strand break. This process is important in meiosis also, where the chromosomes from parents form new allele combination.

Some of the main types are–

- Double-Strand Break Repair (DSBR). It is the classical model in which double Holliday junction is formed, and the resolution of this junction produces crossover or non-crossover products.

- Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing (SDSA). In this step the invading strand is extended by DNA polymerase, then it is displaced and annealed with the second end. It always results in non-crossover product.

- Break-Induced Replication (BIR). It occurs when only one end of DNA break is available for repair, and a long stretch of DNA is synthesized. It is considered a mutagenic type because it produces large changes.

- Single-Strand Annealing (SSA). This process occurs when the repeated sequences flank the break. The DNA ends are resected and both repeated regions anneal, producing a deletion.

- Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination (NAHR). It is the recombination between similar repeated sequences present at different sites, forming deletions or duplications.

2. Non-Homologous Recombination (End Joining)

It is the type of recombination that does not require long homologous regions.

These are–

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ). It is the direct joining of broken DNA ends. It is fast but error-prone, so small insertion or deletion may occur. In immune system it is used in V(D)J recombination to produce antibody diversity.

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ). It is also referred as alternative end joining. Short microhomology of about 5–25 bases is used. Deletion of sequences is common, so it is highly mutagenic.

3. Site-Specific Recombination (SSR)

It is the type in which recombination occurs at specific short sequences catalyzed by recombinase enzymes.

Some examples are–

- Cre-Lox Recombination. The Cre enzyme recognizes loxP sequences. It can produce deletion, inversion or translocation depending on the orientation.

- V(D)J Recombination. It is initiated by RAG1 and RAG2 proteins at specific recognition sequences. Although NHEJ completes the joining step, the process is considered site-specific because it acts only at the defined sites.

4. Other Contextual Types of Recombination

These processes occur in specific biological conditions.

These are–

- Meiotic Recombination. It is the programmed recombination occurring during meiosis. This is important for chromosome segregation and formation of genetic variation.

- Interchromosomal recombination is due to assortment of chromosomes.

- Intrachromosomal recombination occurs due to crossing over.

- Mitotic Recombination. It is used in somatic cells for repairing DNA damage. It mainly forms non-crossover product to avoid chromosome rearrangements.

- Nonhomologous Recombination (General). It refers to recombination between unrelated sequences. It may form chromosomal translocation.

- RNA Virus Recombination. It is the process occurring during RNA replication where the polymerase changes its template, and this produces genetic diversity.

- Engineered Recombination. It includes recombinant DNA technique where DNA from different sources are joined, and genome editing methods like CRISPR/Cas9, which uses cellular repair pathways to introduce specific changes.

1. Homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is the process where the exchange of genetic information takes place between two DNA molecules that are similar or identical in their nucleotide sequence. It is observed in almost all living organisms and it is the main high-fidelity repair system for double-strand break of DNA. It uses a homologous DNA region as the template, so the original sequence is restored accurately. It is also the process that generates new allele combination during meiosis, and it is important for horizontal gene transfer in bacteria.

In this process the broken DNA ends are resected from 5′ to 3′ direction and single-stranded region is formed. These single-stranded regions are coated with proteins like RPA and then recombinase proteins such as RAD51 (RecA in bacteria) is loaded. It is the nucleoprotein filament that finds a homologous sequence on the intact DNA molecule. The 3′ single-stranded end invades the homologous duplex DNA and forms a D-loop structure. DNA polymerase extends this invading strand using the intact DNA as template.

Some of the main types of homologous recombination are–

- Double-Strand Break Repair (DSBR). In this type the double Holliday junction is formed and resolved. In meiosis it mostly produces crossover product.

- Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing (SDSA). In this step the extended D-loop is displaced and anneals with the other broken end. It forms non-crossover product.

- Single-Strand Annealing (SSA). It occurs when repeated sequences flank the break, and the two repeated regions anneal after resection. The intervening region is lost.

- Break-Induced Replication (BIR). It is the process used when only one end of break is available. A long stretch of DNA is synthesized and it is considered a mutagenic pathway.

Homologous recombination is referred to as the accurate repair mechanism, but some types like SSA or BIR can produce mutations or large deletion depending on the sequence structure and the repair condition.

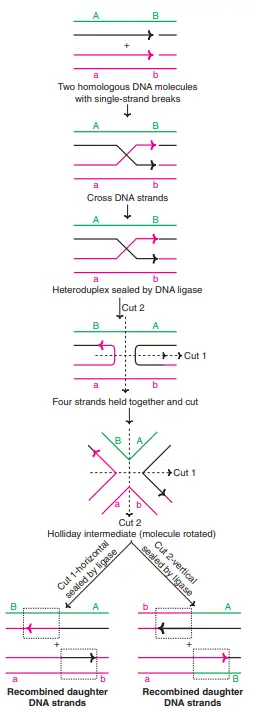

Holliday model

The Holliday model is the classical model that was proposed in 1964 by Robin Holliday to explain how the genetic exchange occurs during meiosis. It is based mainly on the observation of recombination events in fungi where both crossover and non-crossover types are formed. It explains the molecular steps that lead to gene conversion and the formation of new allele combination.

In this model it is assumed that the process starts with the formation of symmetrical nicks on the homologous chromatids. The strands then exchange their partners and a cross-shaped structure is formed, which is referred to as the Holliday junction. This junction is the four-stranded intermediate where the two homologous DNA molecules are connected at one point.

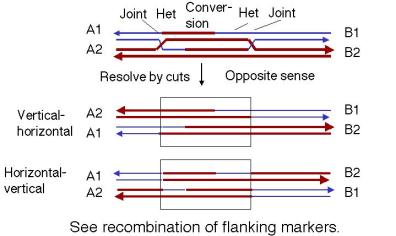

The junction can migrate along the DNA molecule, and this is referred to as branch migration. It forms a heteroduplex region in which the strands from two homologous chromosomes are paired. In the final step the Holliday junction is resolved by specific nuclease enzymes. The cleavage of the junction may occur in two different orientations, and the products formed may be crossover or non-crossover, depending on the direction of cut.

Later studies showed that meiotic recombination mainly starts by double-strand break rather than symmetric nick, so the Holliday model was replaced by the double-strand break repair model. The newer models also described the formation of double Holliday junction and different repair pathways. However, the original Holliday model introduced the concept of the Holliday junction, which is still considered the central intermediate in homologous recombination.

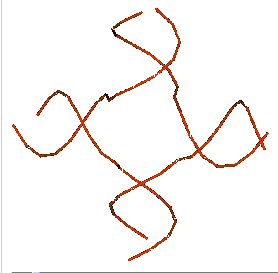

About Above Image: A look at a Holliday intersection. A. An electron micrograph of two DNA double strands in the middle of recombination. B. Holliday junction from X-ray crystallography of a RuvA-Holliday junction complex (from Hargreaves et al., 1998, Nature Structural Biology 5, pp. 441-460). For this view, the RuvA protein tetramer was taken away, and only the phosphodiester backbones of the two duplexes (four strands) are shown. Notice how the DNA in the middle of the structure is twisted. In B form DNA, these are the same as about three nucleotides on each strand that are not paired. The atomic coordinates were downloaded from the Molecular Structure database at NCBI and drawn in Cn3D v.3.0. Each nucleotide in each of the four strands is marked with a letter and a number to show where it is in the chain. On the website for the course, you can find the files you need to see the 3-D image on your own computer.

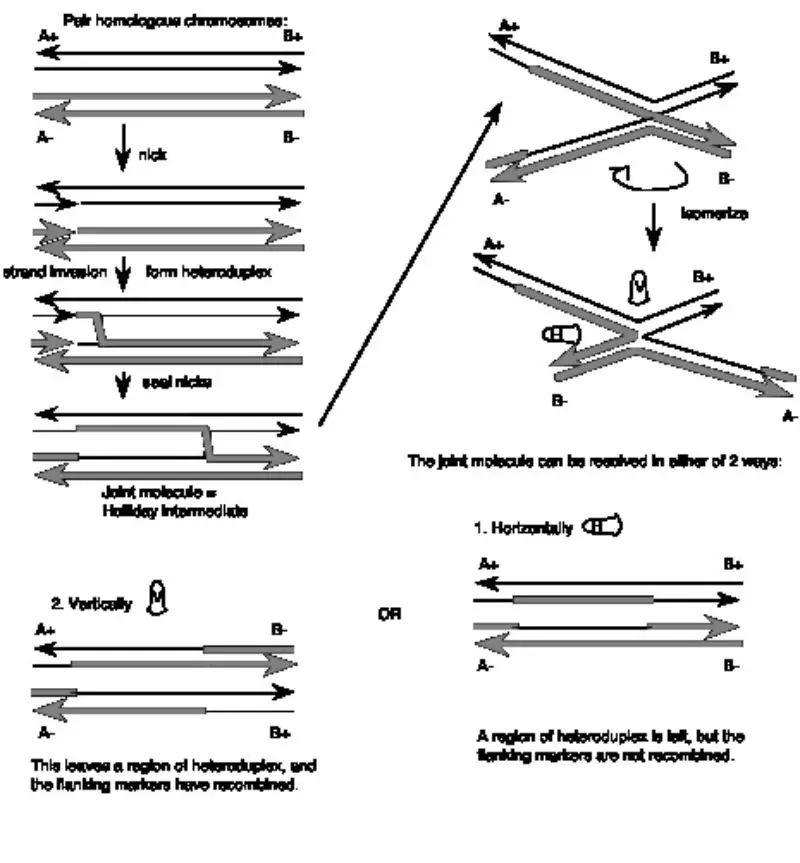

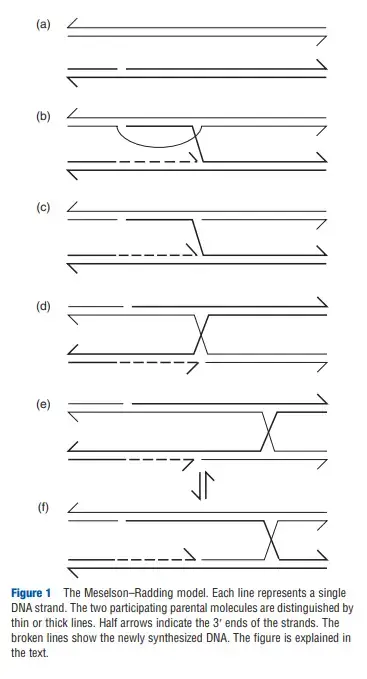

Meselson-Radding model

The Meselson–Radding model is the recombination model that explains how hybrid DNA is formed only on one of the chromatids. It was proposed because many gene-conversion events in Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed an unequal pattern, and this could not be described by the classical Holliday model. It is the process where heteroduplex DNA is produced asymmetrically, and this gives a clear method to understand one-sided gene conversion.

In this model the recombination begins when a single nick is made on one duplex. The 3′-OH formed at the nick is used to start DNA synthesis, and the displaced strand forms a 5′ single-stranded tail. This newly synthesized strand keeps extending and the displaced region grows, giving rise to a D-loop when it invades the homologous duplex. DNA polymerase continues synthesis until an undefined boundary is reached and then the open region of the D-loop is degraded by nucleases.

The result is an asymmetrical heteroduplex region between the site of initiation and the point where DNA synthesis stopped. Wherever the two parental alleles differ, mismatched base pairs appear in this region. After this the intermediate is converted into a Holliday junction. The junction can undergo branch migration, and this forms symmetrical heteroduplex DNA on the other side while keeping the asymmetrical region near the starting point.

The mismatches present in the heteroduplex are corrected by mismatch-repair enzymes. The repair process excises one strand and fills the gap using the complementary strand. This may produce gene conversion, or in some cases postmeiotic segregation.

The Holliday junction formed in this model can isomerize rapidly and exists in two similar states. The resolvase enzyme can cut the strands in either orientation. If the cleavage occurs in one way, it produces a crossover type with exchange of markers. If the cleavage occurs in the other orientation, it forms a non-crossover type. Because both orientations are equally possible, the model predicts that crossover and non-crossover products appear in almost equal proportion.

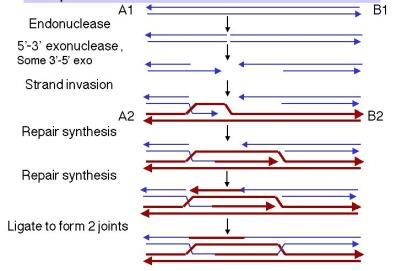

The Double Strand Gap Repair Model

The Double-Strand Gap Repair model can define as a recombination mechanism proposed by Jack Szostak and colleague’s in 1983, and it emerged because evidence in yeast showed that a single nick can’t always explain recombination, especially when one duplex acts as donor while the other behave as recipient.

It is important to note that yeast mating-type switching produces double-strand break’s by HO endonuclease, and these breaks induce recombination between MAT and HML(R) locus, demonstrating that recombination can be triggered by complete cleavage of both DNA strand’s.

In transformed plasmid experiments the “aggressor’’ duplex containing a double-strand gap was repaired using DNA from the donor duplex, and this gap-filling step revealed that recombination initiation requires asymmetric information flow, also this provide sturdy and hardy support for replacing earlier single-nick models.

The mechanism start’s when an endonuclease cuts both strands of one homologous duplex (thin blue in diagrams), After the long meeting we went home, and then an exonuclease widen’s the break to create a gap containing two 3′ single-stranded ends.

One 3′ end invades the homologous donor duplex (thick red), creating a D-loop, and heteroduplex forms in the invaded region,, this loop expands as DNA polymerase synthesizes new strand’s while displacing the donor’s original strand.

The D-loop continues growing until it spans the old gap on the aggressor duplex, the new DNA uses the donor sequence as its template, so the repaired region adopts the sequence of the invaded duplex, even though that physical separation in drawings looks wider than it is in vivo.

When the displaced donor strand anneals to the second 3′ end on the far side of the gap, repair synthesis completes the filling process,, and this step reverses the direction predicted by single-strand invasion models because now the invaded duplex gives information to the aggressor not the other way.

DNA ligase seals nicks on both sides to produce two Holliday junctions, and the molecule shifts in to a recombination intermediate containing heteroduplexes on both sides of the filled gap, with one heteroduplex on the aggressor duplex and another on the donor duplex.

Branch migration can enlarge heteroduplex length from each junction, and perhaps mismatches will appear wherever the two parental allele’s differ, making the structure vulnerable to mismatch-repair correction.

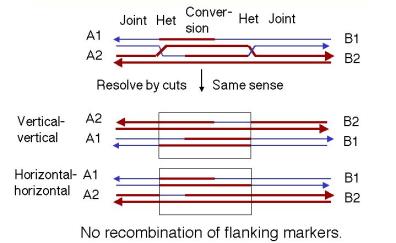

At this stage each Holliday junction may be resolved vertically or horizontally, and because DSB repair carries two junctions the outcome depend’s on whether they are solved the same way or in opposite ways.

If both joints undergo the same resolution (both horizontal or both vertical), no flanking marker recombination appears, although the repaired region shows a footprint of information transfer corresponding to the original gap ± branch-migration range.

If each joint is resolved in different directions, one joint produce a crossover while the other does not,, leading to recombination of flanking markers, and the double-crossover region is so close together that the markers outside remain linked.

Compared with Holliday’s single-nick model, the Double-Strand Break model produces asymmetric heteroduplex arrangement’s, because each duplex carry different heteroduplex patches, and the aggressor duplex is fully converted to match donor sequence across the gap.

In general terms the models still share core steps like single-strand creation, homology searching, D-loop formation, branch migration, and resolution; moreover enzyme’s for each step have been identified, giving a comprehensive system that explain’s recombination across many organism’s.

Recombination Models and Segregation Patterns

The models should be applied to the four chromatid stage of the meiotic cell. Remember that there are two chromosomes containing red DNA and two chromosomes containing green DNA in the region of interest. As depicted in the models, we consider the exchange between a red DNA duplex and a green DNA duplex and derive the effects of the exchange on the segregation pattern.

- Holliday model———-> Symmetric heteroduplex ———> Two colonies with half-sectors in yeast by germination of the four spores from a meiotic event; two pairs of non-identical sister spores in Ascobolus. 4: 4 aberrant segregation.

- Meselson-Radding model———-> Asymmetric heteroduplex———-> One sectored colony in yeast; one pair of non-identical sister spores in Ascobolus. 5:3 aberrant segregation.

- Double strand gap repair model———-> Conversion of green DNA to red DNA in the region of repair. 6:2 aberrant segregation.

Homologous Recombination in Eukaryotes

Homologous recombination in eukaryotes is the process that repair the DNA when the strands are damaged by radiation, chemicals, or replication stress. It is considered the accurate way of repairing double-strand break because the sister chromatid provide the homologous sequence that act as the template. It is the process that prevents the formation of mutation which may destabilize the genome if the broken DNA is not corrected.

In mitosis this process uses the homologous region of the sister chromatid. It is the reliable method because the copied DNA region is almost identical, so the missing information is restored even when the original strand is highly damaged. If these breaks are not repaired, the chromosomes may show rearrangement or abnormal amplification, so the recombination-based repair is essential for maintaining the stability of DNA.

In eukaryotic meiosis homologous recombination also create variation. The gametes like ovum and sperm undergo meiotic division, and during this stage the homologous chromosomes pair and exchange segments. This is referred to as chromosomal crossover. The new allele combinations formed in this step help in producing variation in every generation. It is important for adaptation although sometimes the crossover position may form uneven heteroduplex region.

The crossover formation occurs by pairing of homologs, strand invasion, formation of Holliday-type intermediate and its resolution. In meiosis these steps are tightly regulated and the heteroduplex patches may show asymmetry depending on the repair pattern.

Overall, homologous recombination in eukaryotes maintain the genome integrity on one side by repairing the breaks and on the other side it forms genetic variation which is an important factor in evolution.

Disadvantages of Homologous Recombination

- It may produce unwanted genomic rearrangement when the chromosomes misalign during the exchange, and this can form deletion or duplication of DNA segments.

- The process sometimes increases genomic instability because faulty recombination can produce chromosomal aberration and aneuploidy.

- It can cause loss of heterozygosity, and this may expose the recessive harmful allele which increase the risk of genetic disease.

- Improper recombination is associated with different disorders, and some cancer types also show defective recombination during cell division.

- If the exchanged region contain harmful mutation, the recombination may spread that mutation, and in cancer cells it may also produce drug-resistant types.

- In genetic engineering it may create unintended gene change, and this affects the accuracy of gene-targeting results.

- Clinical testing of homologous recombination status may not always represent the actual disease condition, so false result can make treatment decision difficult.

Applications of Homologous Recombination

- It is used in gene targeting where a specific gene is knocked out or replaced, and this help in studying the function of that gene in different model organisms.

- It is used in recombineering for precise insertion or deletion of DNA sequence in plasmid or chromosome, and the process does not require restriction enzyme or ligase.

- It helps in tagging proteins by inserting fluorescent marker sequence at the desired gene location, so the movement and expression of the protein can be studied inside the cell.

- It is used in understanding the DNA repair pathways for double-strand break and gives important information related to cancer research.

- It plays a role in horizontal gene transfer in bacteria, and this exchange of sequence helps in studying evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance.

- It is used in therapeutic gene correction where the mutated gene is replaced by the correct sequence for treatment of different genetic disorder.

2. Non-homologous recombination

Non-homologous recombination is the process where the DNA strands join without using any homologous sequence as the template. It is mainly used in repairing double-strand break when no identical region is available. It is considered an error-prone type because the broken ends are ligated directly, and small sequence change may occur during the repair.

1. Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

It is the major pathway for repairing break in DNA, especially in G1 phase.

- In this process the broken DNA ends are captured and brought together, and then ligated directly.

- It does not need long homologous region, so the sequence at the joining site may show insertion or deletion.

- The process begins when Ku70/Ku80 complex binds to the broken ends, and then DNA-PKcs, Ligase IV and XRCC4 help in the joining of ends.

- It is also used in V(D)J recombination where the RAG1 and RAG2 enzyme create double-strand break at specific sequence, and the NHEJ system complete the joining step.

2. Alternative End Joining (A-NHEJ)

When classical NHEJ is not available the cell uses the alternative pathway.

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) is the main type.

- In this type short microhomology of about 5–25 bases is used to align the DNA ends.

- The DNA is resected from 5′ to 3′, and then the microhomologous region anneal.

- It always produces deletion or complex change, so it is considered highly mutagenic.

- These pathways may form translocation or other rearrangement and are often linked with cancer cells due to clustered break repair.

Transposition

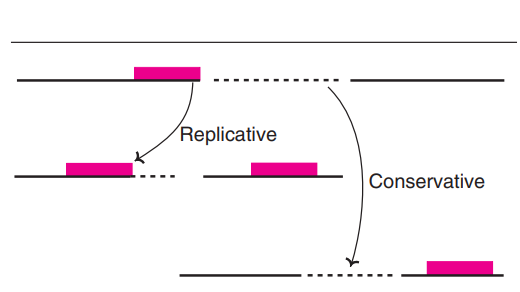

- Transposition can be defined as a process where a DNA element moves from one genomic location to another,And this movement usually happen’s without the need for long sequence homology.

- It is well known that these Mobile Element’s (like Transposon’s, or “jumping gene’s”) are recognized by enzyme’s such as Transposase, the reaction then cut’s or copy’s the segment and insert it in to a new site.

- In the cell, the insertion often produce’s short duplicated sequence’s at the target, this occur because the Host DNA gets staggered cut’s during integration.

- This movement also alters Genome Architecture, sometimes creating mutation’s or changing gene expression, the effect’s can be either mild or strongly disruptive.

- Over the past few decades researchers have noted that transposition appear in both Prokaryotes / Eukaryotes, And the rate depend on stress condition’s, chromatin state, etc.

- The process is considered one of the key mechanism’s shaping evolutionary plasticity, giving a look into how new regulatory modules arise, even though some insertion’s prevail proper function.

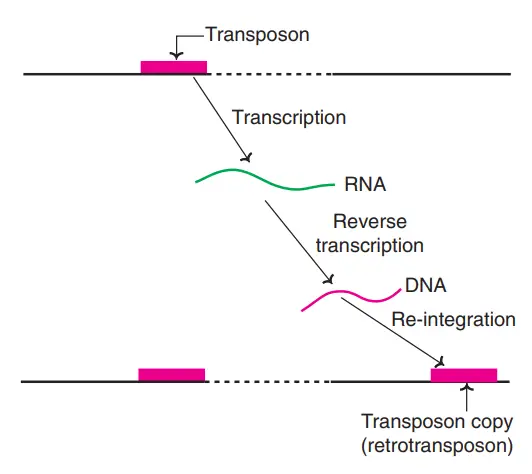

Retrotransposition

- Retrotransposition can be defined as a molecular process where a genetic element is copied through an RNA intermediate,And then that RNA is turned back in to DNA before insertion at a new genomic site.

- It is important to note that this pathway is characteristic of LINE’s, SINE’s, and retroviral-like element’s, which rely on Reverse Transcriptase (RT) enzyme’s to make cDNA copy’s.

- In the cell cytoplasm the transcript is produced, then transported back toward nucleus,And the integration machinery insert’s it with little regard for surrounding homology.

- This mechanism also generate’s target-site duplication’s due to staggered nicking in host DNA, giving a look into how repetitive architecture accumulate’s.

- Over the past few decades many studies showed that retrotransposition rate is influenced by chromatin openness / epigenetic marks,etc., the regulation is inconsistent across tissues.

- The resulting insertion sometimes disrupt gene’s, sometimes create new regulatory module’s, it seems these changes contribute to genome evolution and also unpredictable mutational load.

DNA transposition

- DNA transposition can be defined as the movement of a discrete DNA segment (a Transposon) from one chromosomal site to another,And this relocation usually occur’s without need for extended homology.

- It is worth mentioning that the movement is mediated by Transposase enzyme’s, which cut or copy the element and shift it in to a fresh genomic position.

- During integration the Host DNA often receive’s staggered break’s, creating short duplicated sequence’s that flank the inserted element, this pattern is common in many organism’s.

- This mechanism also alters Genome Structure, sometimes generating mutation’s or affecting gene’s expression, yet in other cases the change’s seem neutral.

- In recent years researchers found DNA transposition in Prokaryotes / Eukaryotes, And rate’s are shaped by chromatin openness, cellular stress etc.

- The process provide’s a powerful force in genome evolution, it creates new arrangement’s and sometimes prevail proper gene function, giving a look into how complex architectures arise.

Significance of transposition

- Transposition has been recognized as a major force shaping Genome Architecture,And it introduce’s new arrangements that sometimes change how nearby gene’s behave.

- It is important to note that moving element’s contribute to genetic diversity since their insertion or excision create mutation’s, duplication’s, or small deletion’s that accumulate over time.

- In evolutionary Biology the process also provides raw material for new regulatory module’s, the inserted sequences occasionally serve as promoter-like motifs or enhancer’s.

- Some Transposon’s carry gene’s for antibiotic resistance, so their mobility help’s spread adaptive traits across bacterial population’s, this happen even under 37°C/ 38 °C stress.

- The movement also generate’s chromosomal rearrangement’s like inversions or translocations, giving a look in to how structural variation arises in many organism’s.

- It has been shown that transposition events can activate or silence gene’s through epigenetic response’s, And host genome’s evolve mechanism’s to restrict them.

- In general terms the process contribute’s to long-term genome plasticity, although some insertion’s prevail stable function and lead to harmful phenotypes etc.

- (2008). Meselson-Radding Model Of Recombination (1975 Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 72:358). In: Encyclopedia of Genetics, Genomics, Proteomics and Informatics. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6754-9_10182

- Hastings, P. J. (2013). Meselson–Radding Model. Brenner’s Encyclopedia of Genetics, 364–365. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-374984-0.00927-x

- Gibb, Bryan. (2010). Requirements for Catalysis in Cre Recombinase.

- https://www.slideshare.net/rahulmanjunath2/site-specific-recombination

- https://m.blog.naver.com/pcshgu98/221670950029

- https://www.web-books.com/MoBio/Free/Ch8D7.htm

- https://www.slideshare.net/RoshanParihar2/site-specific-recombination-124785829

- https://www.bx.psu.edu/~ross/workmg/RecombineDNACh8.htm

- https://sites.cns.utexas.edu/sites/default/files/bio-366/files/bio-366-web-horecom-models-sep4-2018.pdf?m=1536084235

- https://microbiology.ucdavis.edu/heyer/wordpress/research/homologous-recombination

- https://www.creative-diagnostics.com/non-homologous-end-joining-pathway.htm

- http://genesdev.cshlp.org/content/19/22/2715.short

- https://www.cureffi.org/2014/10/06/molecular-biology-13/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-homologous_end_joining

- http://www.sbs.utexas.edu/jayaram/Bio-366/BIO-366-Homologous%20Recombination/BIO-366-Recombination%20Models.pdf