Through the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito (Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus), dengue viruses are transmitted to people. These mosquitoes can transmit other viruses including Zika and chikungunya.

4 billion people, or close to half of the world’s population, reside in dengue-risk zones. In risky locations, dengue is frequently the main cause of sickness.

Dengue affects up to 400 million people annually. A hundred million people worldwide develop an infection, and severe dengue causes 40,000 fatalities.

One of the four closely related dengue viruses—dengue viruses 1, 2, 3, and 4—causes the disease. Because of this, a person may contract the dengue virus up to four times in a lifetime.

What is Dengue and Dengue Virus?

Dengue is a viral illness that is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected Aedes mosquito. It is a leading cause of illness and death in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, particularly in Asia and Latin America.

Dengue is caused by one of four closely related viruses: dengue virus 1, dengue virus 2, dengue virus 3, and dengue virus 4. These viruses are members of the flavivirus family and are transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, which are common in tropical and subtropical regions.

Symptoms of dengue fever can range from mild to severe and typically appear 3 to 14 days after the bite of an infected mosquito. Symptoms can include fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, rash, and swollen glands. In severe cases, dengue can lead to dengue hemorrhagic fever, which is a potentially life-threatening complication characterized by bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, and damage to the lymph and blood vessels.

There is no specific treatment for dengue fever, and treatment is generally supportive, with a focus on managing symptoms and preventing complications.

To prevent dengue fever, it is important to take measures to avoid mosquito bites, such as using insect repellent, wearing long-sleeved clothing, and sleeping under a mosquito net. It is also important to eliminate mosquito breeding sites by eliminating standing water where mosquitoes can lay their eggs.

Characteristics of Dengue Virus

- There are four different serotypes of the dengue virus, known as DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3, and DEN-4.

- They are members of the family Flaviviridae, which includes about 70 viruses and whose type species is the yellow fever virus (150).

- The flaviviruses have a lipid envelope and are round and relatively tiny (40–50 mm). Three structural proteins and seven nonstructural proteins make up the roughly 11,000 base flavivirus genome.

- The tick-borne encephalitis virus, the Japanese encephalitis virus, and the dengue virus are the three main complexes that make up this family.

- On the envelope protein, all flaviviruses share group epitopes that cause numerous cross-reactions in serological assays. These make it challenging to achieve an accurate serologic diagnosis of flaviviruses.

- Particularly among the four dengue viruses, this is true. There is no cross-protective immunity to the other dengue serotypes, but infection with one of them confers lifetime immunity to that particular virus. Therefore, individuals who live in a region where dengue is endemic can contract three, and most likely four, dengue serotypes over their lifetime.

Structure and Genome of Dengue Virus

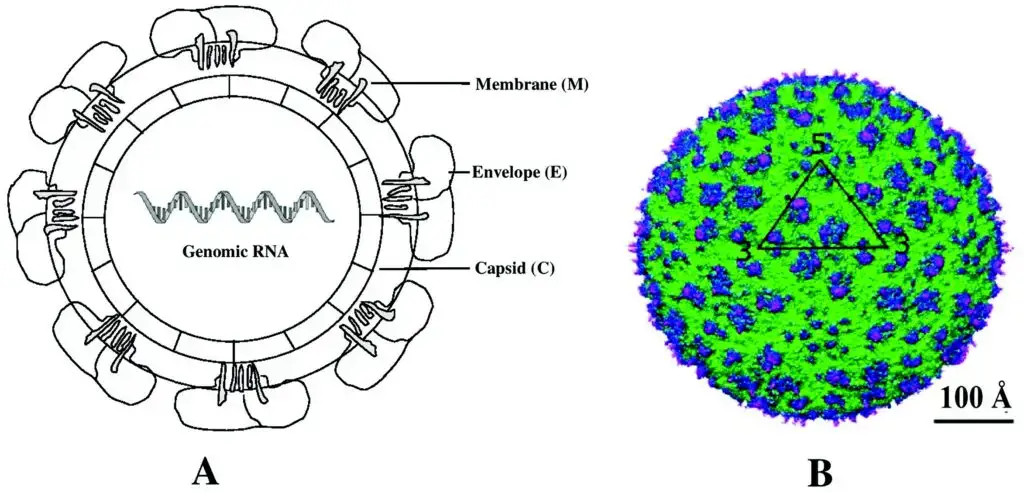

- Dengue virions were discovered to be spherical, with a diameter of around 50 nm, a reasonably smooth surface, a well-organized exterior protein layer on the surface of a lipid bilayer, and an inner nucleocapsid core.

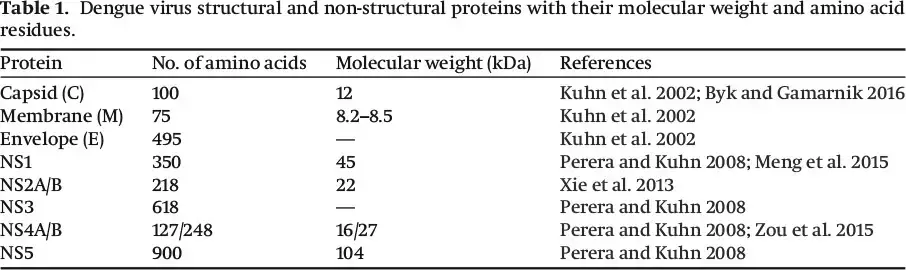

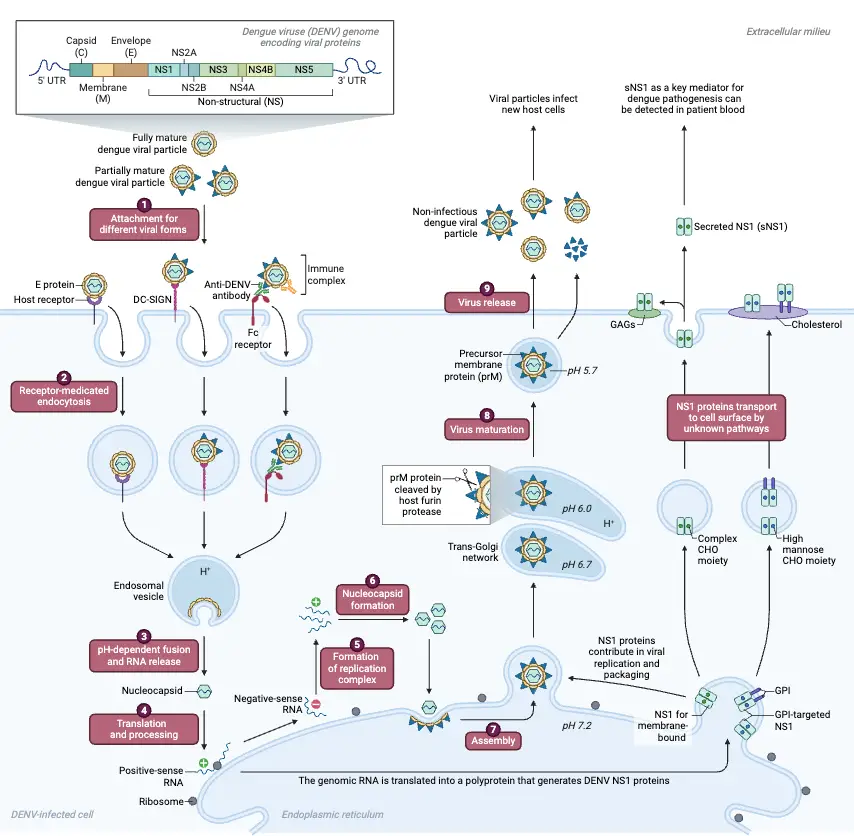

- Three structural proteins—the capsid (C), membrane (M), and envelope (E)—as well as seven non-structural proteins—NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5—are present in DENV.

- The structural and non-structural DENV proteins are included in Table along with brief descriptions.

- Cryo-electron microscopy image reconstructions revealed that the virion envelope possesses icosahedral symmetry, with E protein dimers arranged in a herringbone-like pattern .

- The spherical immature and mature particles have an ER-derived outer membrane and E and M proteins, which together form an icosahedral-shaped outer glycoprotein surface.

- Within the lipid bilayer is an RNA-protein core made up of a positive-sense ssRNA genome and capsid proteins (C).

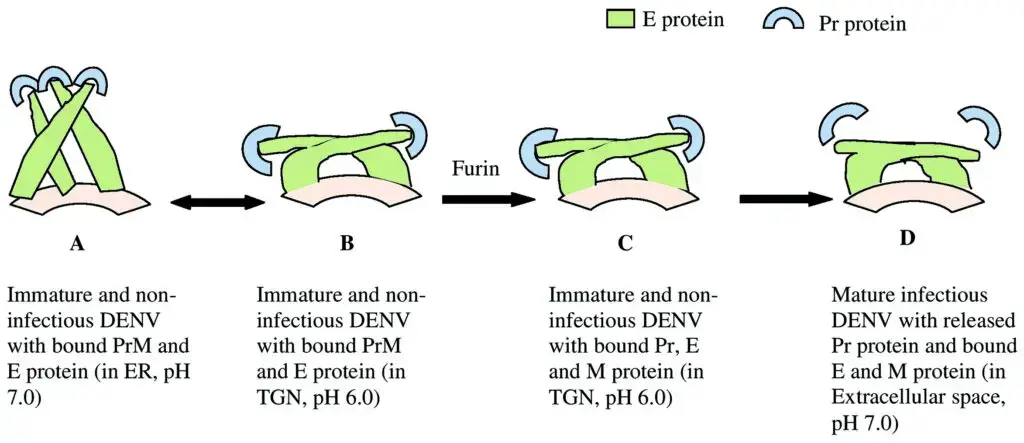

- Depending on the conformational alterations of M and E proteins at various ambient pH levels, DENV in its mature and immature phases can be both infectious and non-infectious.

- The E protein undergoes conformational changes that cause the structural transition from immature (spiky) to mature (smooth) shape during passage through the trans-Golgi network (TGN).

- Before DENV matures, membrane-bound E proteins change their shape in the TGN (low pH). After maturation, the Pr peptide, which has infectious capabilities, is released from the E protein in the extracellular environment (pH 7.0).

- The non-structural proteins NS1, NS2A, NS4A, and NS44B have virtually little known about their molecular structures. The suppression of complement activation by NS1 aids in viral defence as well as viral RNA replication.

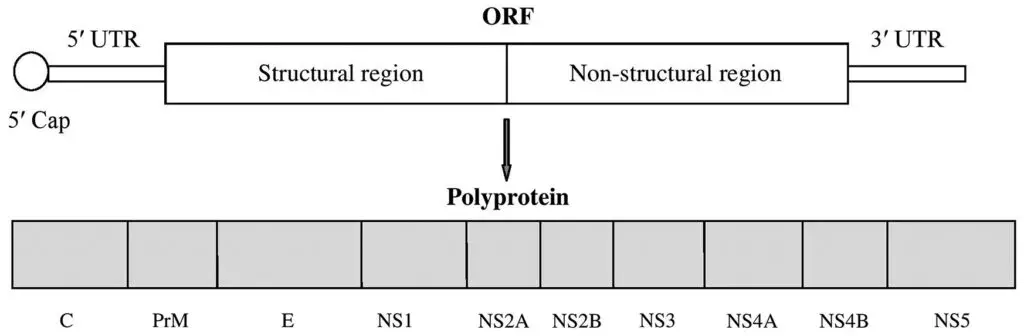

- The creation of a portion of the replication complex involves NS2A and NS4B. The DENV genome is an 11 kilobase-long, positive (+) single-stranded RNA.

- The 5′ UTR region (untranslated region), the ORF (open reading frame), and the 3′ UTR region make up the RNA genome.

- The genome lacks a poly (A) tail at the 3′ end and has a type I cap (m7GpppAmp) at the 5′ end with a single ORF that encodes a polyprotein.

Intracellular replication of Dengue

- Following a successful infection, DENV predominantly targets dendritic cells for assault and replication before infecting macrophages, monocytes, and lymphocytes.

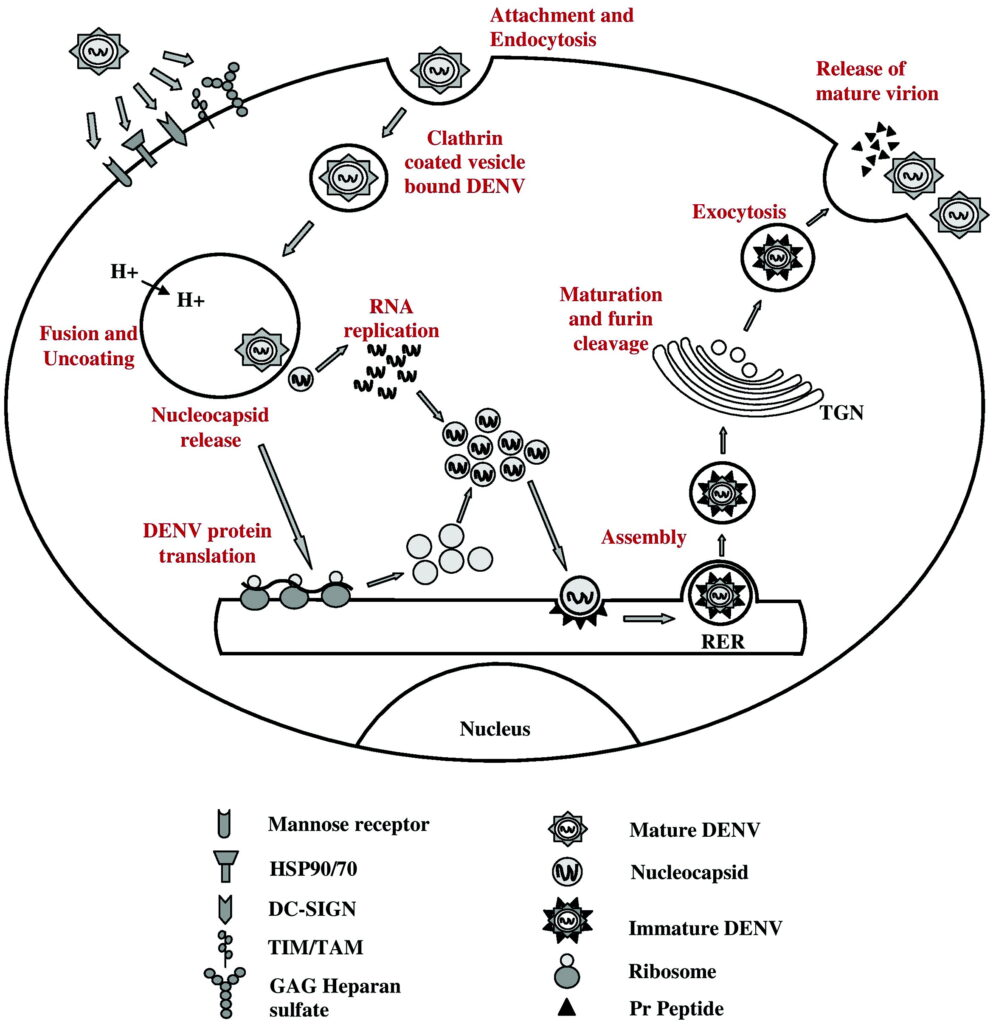

- Cell surface molecules such as Fc receptors, glycosaminoglycans (GAG), lipopolysaccharide-binding CD14 related molecules, heparan sulphate, and lectin-like receptors, such as DC-SIGN, are used to enter the cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis (dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing non-integrin). Using clathrin-coated vesicles, DENV enters the cell.

- The union of the viral and host cell membranes and subsequent release of the nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm are caused by acidification of the late-endosomes, which changes the structure of the E protein.

- The acidic pH of the endosome facilitates the fusion of the virus with the membrane. The viral components are then carried to the ER by the cytoskeletal transport machinery once the nucleocapsid (NC) is released into the cytoplasm and the RNA genome is uncoated.

- First, a polyprotein is produced from the positive-stranded RNA of DENV in a cap-dependent way. Positive-sense RNA serves as a template for the RNA genome replication that takes place at the ER membrane. For the synthesis of both negative- and positive-strand viral RNA, the DENV NS5 protein, which has RNA cap methylation and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) activity, is necessary.

- While viral E and M proteins are introduced into the ER membrane during translation, viral capsid proteins are translated in the cytoplasm.

- The genomic RNA is encapsidated by the capsid proteins in the cytoplasm and buds into the lumen of the ER, where it picks up the M (produced by the cleavage of PrM by host protease, furin, MW 57 kDa) and E containing envelope from the ER, once sufficient positive-sense RNA copies have been transcribed from negative anti-genome RNA.

- During virion assembly and release, the E protein’s structure and organisation on the mature virion surface alter depending on pH.

- The trans-Golgi network and ER are traversed by the enveloped viruses, which stay in the lumen. The encased virions sprout through the ER membrane into the cytoplasm in the last phase, receiving a second outer membrane produced from the ER.

- The mature offspring virions that have been encased are subsequently released into the extracellular space where they can disseminate and infect nearby cells once this ER membrane merges with the plasma membrane.

Epidemiology of Dengue

- Dengue is a viral illness that is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected Aedes mosquito. It is a leading cause of illness and death in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, particularly in Asia and Latin America.

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), dengue is a leading cause of illness and death in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, with an estimated 390 million infections occurring each year. The WHO estimates that around 2.5% of these infections result in severe dengue, which can lead to dengue hemorrhagic fever and death.

- Dengue is most common in areas with a high population density and poor sanitation, as these conditions are conducive to the breeding of Aedes mosquitoes. The risk of dengue is highest during the rainy season, when mosquito populations are at their peak.

- Dengue is a major public health concern in many countries, and efforts are being made to control the spread of the virus through measures such as the use of insecticides and the elimination of mosquito breeding sites.

Transmission of Dengue Virus

Mosquito Bites

The bites of infected Aedes species mosquitoes transmit the dengue virus to humans (Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus). These are the same mosquito species that transmit the chikungunya and zika viruses.

- These mosquitoes often deposit their eggs in water-holding containers including buckets, bowls, animal dishes, flower pots, and vases close to areas where there is standing water.

- These mosquitoes are found both indoors and outdoors close to people, where they like to bite.

- Dengue, chikungunya, and Zika-carrying mosquitoes bite both during the day and at night.

- When a mosquito bites a host who has the virus, it becomes infected. The virus can then be transmitted to further people by infected mosquito bites.

Mother to child

- When a woman is pregnant or shortly after giving birth, she can transmit the dengue virus to her foetus.

- There has only ever been one confirmed case of dengue spreading through breast milk. Mothers are advised to breastfeed even in dengue-risk areas because of the advantages of doing so.

Through infected blood, laboratory, or healthcare setting exposures; Rarely, a needle stick injury, organ transplant, or blood transfusion can spread dengue.

Pathogenesis of Dengue

- Although some individuals can develop hemorrhagic fever, the majority of dengue infections with a particular serotype remain asymptomatic and only result in moderate febrile sickness.

- Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) or dengue shock syndrome may result from secondary infection with a different serotype (DSS).

- An human develops immunity against a serotype of a virus after infection with that serotype; nevertheless, they remain susceptible to future infections from other serotypes of the virus since heterologous immunity fades progressively over 1-2 years.

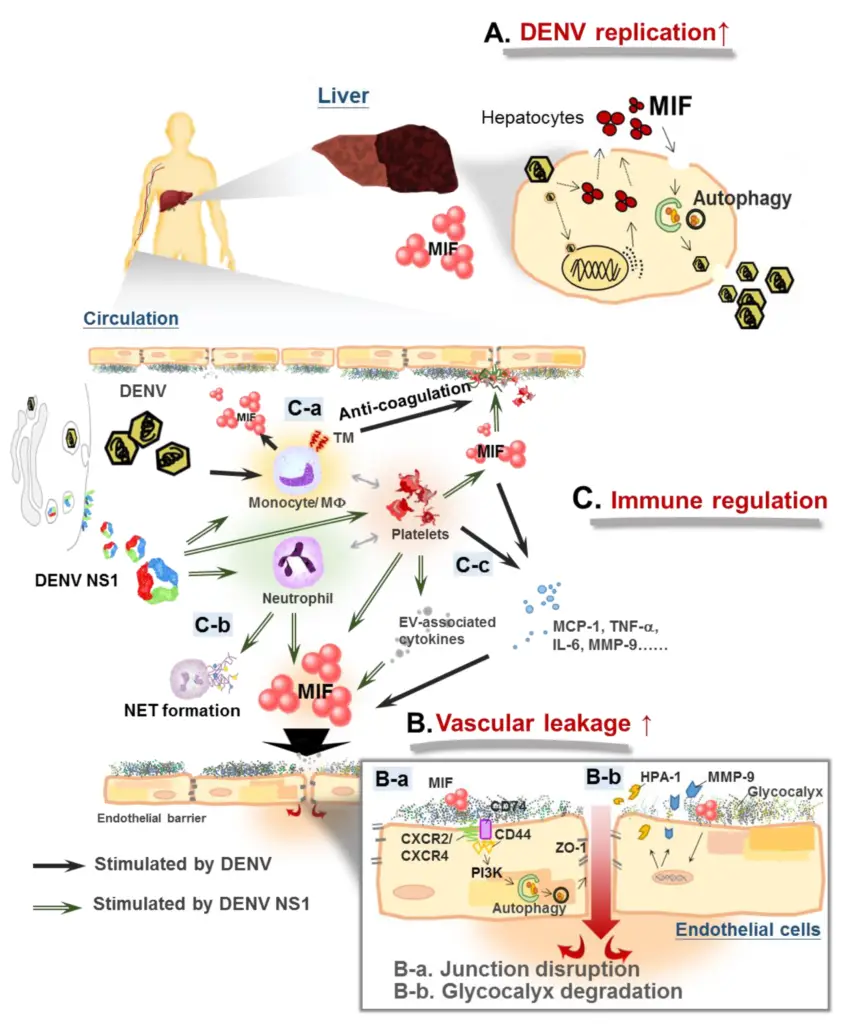

- Numerous viral and host factors, including the non-structural protein 1 (NS1) viral antigen, dengue virus genome variants, subgenomic RNA, antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), T-cells, anti-DENV NSI antibodies, and autoimmunity, contribute to the pathogenesis of DENV.

- After the virus enters a person’s bloodstream from a mosquito bite, it infects surrounding skin cells and Langhans cells, which are specialised immune cells.

- The viral antigen is then displayed on the surface of Langerhans cells, which migrate to lymph nodes and contribute to the activation of the innate immune response.

- In addition to infecting macrophages and monocytes, the dengue virus spreads throughout the body, resulting in viremia in the individual.

Immune response

- In order to combat the virus, infected cells release interferons, a type of cytokine that inhibits viral replication and stimulates both the innate and adaptive immune responses.

- Once the adaptive immune response is activated, B cells release IgM and IgG antibodies into the blood and lymph fluid.

- These cells identify viral particles and contribute to their neutralisation.

- Additionally, cytotoxic T cells contribute to the adaptive immune response.

- The innate immune response also activates the complement system.

Clinical Manifestations of Dengue

The clinical manifestations of dengue fever can vary from person to person, but common symptoms include:

- Fever

- Severe headache

- Pain behind the eyes

- Joint and muscle pain

- Rash

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Abdominal pain

In severe cases, dengue fever can lead to dengue hemorrhagic fever, which is a more serious form of the disease that can cause bleeding and damage to the immune system. Symptoms of dengue hemorrhagic fever can include:

- Severe abdominal pain

- Persistent vomiting

- Rapid breathing

- Bleeding from the gums or nose

- Easy bruising

- Blood in the urine, vomit, or stool

Diagnosis of Dengue Virus/Detection of dengue

There are several methods that can be used to diagnose dengue virus infection. These include:

- Virus isolation: This involves taking a sample of blood from the patient and attempting to grow the virus in a laboratory setting. This method is time-consuming and not commonly used.

- Antigen detection tests: These tests detect proteins called antigens that are produced by the virus. Antigen detection tests can be performed on a sample of blood or on other body fluids, such as urine or saliva.

- Antibody detection tests: These tests detect antibodies produced by the body in response to the virus. Antibody detection tests can be performed on a sample of blood or on other body fluids, such as urine or saliva.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): This test uses a small sample of blood to amplify and detect the genetic material of the virus. PCR is a sensitive and specific method for detecting dengue virus, but it requires specialized equipment and trained personnel to perform the test.

Treatment of Dengue

- There are no specific treatments for dengue.

- Get as much rest as you can.

- Acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol outside the United States) is used to reduce fever and alleviate pain.

- Avoid taking aspirin and ibuprofen.

- Consume a lot of fluids to maintain hydration. Consume water or beverages containing electrolytes.

- Care for a sick infant, kid, or family member at home for minor symptoms.

- Immediately consult a healthcare provider or go to the emergency department if you have any warning signals.

- Severe dengue is a medical emergency. It necessitates quick medical attention at a clinic or hospital.

Vaccines of Dengue

There are several vaccines that have been developed to prevent dengue virus infection. The most widely used vaccine is called Dengvaxia. This vaccine is approved for use in people ages 9 to 45 who live in areas where dengue is prevalent.

Dengvaxia is a live, attenuated vaccine, which means that it contains a weakened form of the virus. It is administered in a series of three injections given six months apart. The vaccine has been shown to be effective at reducing the risk of dengue fever, but it is not 100% effective. Some people who receive the vaccine may still develop dengue fever, but the illness is usually less severe in vaccinated individuals.

Other dengue vaccines are also in development and are being tested in clinical trials. It is not yet clear when these vaccines will be available for widespread use.

It is important to remember that vaccines are just one tool that can be used to prevent dengue virus infection. Other prevention measures, such as reducing mosquito breeding sites and using insect repellent, are also important in reducing the risk of dengue virus transmission.

Prevention and control of Dengue

- Prevent dengue by avoiding mosquito bites.

- All four dengue viruses are predominantly transmitted via the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito (Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus). These mosquitoes also transmit the zika and chikungunya viruses.

- There are dengue-carrying mosquitoes in the majority of tropical and subtropical regions of the world, including many sections of the United States.

- Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus are daytime and nighttime biters.

- A dengue vaccination is currently recommended for American Samoa, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, as well as the freely connected states of the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau.

Prevent Mosquito Bites

- Dengue is transmitted to humans via the bite of an infected mosquito.

- Dengue-carrying mosquitoes feed during the day and night. These mosquito species also transmit the chikungunya and Zika viruses.

- The most effective strategy to prevent these infections is to avoid mosquito bites.

Protect Others

- During the initial week of illness, the dengue virus is detectable in the blood of infected individuals. If an infected individual is bitten by a mosquito, the mosquito will become infected. The infected mosquito can transmit the virus to humans through its bites.

- Not everyone who contracts dengue becomes ill. Even if you do not feel ill, visitors returning to the United States from a region with a risk of dengue should take preventative measures against mosquito bites for three weeks so they do not spread the virus to mosquitoes that could infect others.

References

- Hottz, E., Tolley, N. D., Zimmerman, G. A., Weyrich, A. S., & Bozza, F. A. (2011). Platelets in dengue infection. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Mechanisms, 8(1-2), e33–e38. doi:10.1016/j.ddmec.2011.09.001

- Gubler, D. J. (2008). Dengue Viruses. Encyclopedia of Virology, 5–14. doi:10.1016/b978-012374410-4.00380-0

- Vaughn, D. W., Whitehead, S. S., & Durbin, A. P. (2009). Dengue. Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases, 285–324. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-369408-9.00019-6

- Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998 Jul;11(3):480-96. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.3.480. PMID: 9665979; PMCID: PMC88892.

- https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/Dengue-virus-disease

- https://microbenotes.com/dengue/

- https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/cjm-2020-0572

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dengue/

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17753-dengue-fever

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue#:~:text=Dengue%20is%20a%20viral%20infection,called%20dengue%20virus%20(DENV).

- https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/index.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/about/index.html

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/dengue-fever/symptoms-causes/syc-20353078