- Diverse species of bacteria, known as gut microbiota, occupy the gastrointestinal system of humans. There are 1010–1012 living bacteria per gramme in the human colon, according to reports.

- The resident microbial communities of the human stomach, small intestine, and large intestine are essential for human health. The majority of these predominantly anaerobe bacteria reside in the large intestine.

- Although some endogenous variables, such as mucin secretions, might impact the balance of microorganisms, the primary source of energy for their growth is the human food. Non-digestible carbohydrates can significantly alter the makeup and function of gut bacteria.

- Beneficial intestine microorganisms ferment these nondigestible food items, known as prebiotics, and derive their life energy from decomposing prebiotic bonds that are indigestible. As a result, prebiotics can impact gut flora selectively.

- In contrast, the gut microbiota influences intestinal activities such as metabolism and intestinal integrity.

- In addition, they are able to suppress infections in healthy humans by inducing immunomodulatory molecules with antagonistic effects against pathogens in response to lactic acid produced by the genera Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

- Numerous substances have been evaluated to establish their prebiotic properties. The most prevalent prebiotics are fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), and trans-galacto-oligosaccharides (TOS).

- The short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) lactic acid, butyric acid, and propionic acid are produced by the fermentation of prebiotics by gut microbes. These products may have multiple physiological consequences.

- Propionate, for instance, impacts T helper 2 in the airways, macrophages, and dendritic cells in the bone marrows. SCFAs reduce the pH of the colon.

- Peptidoglycan is an additional prebiotics fermentation product that can activate the immune system’s innate response against pathogenic bacteria. The fermentation products are determined by the structure of prebiotics and the bacterial composition of the digestive tract.

- The effects of prebiotics on human health are mediated by their microbial breakdown products. For instance, butyrate influences the growth of intestinal epithelial cells.

- Due to the fact that SCFAs can diffuse into the bloodstream via enterocytes, prebiotics have the potential to affect not just the gastrointestinal tract but also distant organs.

Definition of Prebiotics

- The concept of prebiotics was initially suggested by Glenn Gibson and Marcel Roberfroid in 1995. Prebiotic was defined as “a non-digestible food element that promotes host health by selectively encouraging the growth and/or activity of one or a restricted number of beneficial bacteria in the colon.”

- This definition has remained virtually constant for over 15 years. According to this criteria, only a few carbohydrates can be classed as prebiotics, including short and long chain β-fructans [FOS and inulin], lactulose, and GOS.

- In 2008, the 6th Meeting of the International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) defined “dietary prebiotics” as “a selectively fermented ingredient that causes specific changes in the composition and/or activity of the gastrointestinal microbiota, thereby conferring health benefits to the host.”

- A compound is classified as a prebiotic if it meets the following criteria: I it should be resistant to the acidic pH of the stomach, cannot be hydrolyzed by mammalian enzymes, and should not be absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract; (ii) it can be fermented by intestinal microbiota; and (iii) the growth and/or activity of the intestinal bacteria can be selectively stimulated by this compound, and this process improves the health of the host.

- Although not all prebiotics are carbohydrates, fibre can be distinguished from carbohydrate-derived prebiotics using the following two criteria: I fibres are carbohydrates with a degree of polymerization (DP) equal to or greater than 3, and (ii) endogenous enzymes in the small intestine cannot hydrolyze them. It should be considered that the solubility or fermentability of the fibre is not significant.

- Several revised definitions of prebiotics have also been presented in the scientific literature. However, the 2008 definition indicated above has been widely accepted in recent years.

- Despite the lack of a consensual definition, the most significant aspect of the original and additional definitions is that prebiotic intake is connected with human health.

- In the original definition, “selectivity” referred to the ability of a prebiotic to encourage a certain gut flora; however, this concept has lately been questioned.

- Scott et al. (2013) reported that cross-feeding, defined as the consumption of one species’ products by another, boosted the prebiotic impact.

- This conclusion calls into question the use of the term “selectivity” in the prebiotics definition. A historical overview of the evolution of prebiotics may be found in a previous paper, and the concept of prebiotics is currently under controversy.

Types of Prebiotics

There are numerous varieties of prebiotics. The majority of them are a subset of carbohydrate groups and are largely oligosaccharide carbohydrates (OSCs) (OSCs).

1. Fructans

- This category includes inulin, fructo-oligosaccharides, and oligofructose. Their structure consists of a linear fructose chain with β(2→1) linkage.

- Typically, they have terminal glucose units connected by β(2→1) linkage.

- Inulin has a DP of up to 60 whereas FOS has a DP of less than 10.

2. Galacto-Oligosaccharides

- Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), the outcome of lactose extension, are divided into two subgroups: I GOS with extra galactose at C3, C4, or C6; and (ii) GOS produced from lactose via enzymatic trans-glycosylation.

- This reaction produces mostly a mixture of tri- to pentasaccharides including galactose in β(1→6), β(1→3), and β(1→4) links.

- This form of GOS is also known as TOS or trans-galacto-oligosaccharides.

- GOSs can considerably boost Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli.

- Infant Bifidobacteria have demonstrated strong GOS incorporation.

- GOS also stimulates Enterobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes, but to a lesser amount than Bifidobacteria.

3. Starch and Glucose-Derived Oligosaccharides

- There is a type of starch called as resistant starch that is resistant to digestion in the upper digestive tract (RS).

- It has been claimed that RS should be categorised as a prebiotic because it produces a high level of butyrate. Diverse Firmicutes groupings have the highest incorporation of RS.

- In vitro research indicated that Ruminococcus bromii, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Eubacterium rectale, and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicrobe were also capable of degrading RS.

- In the mixed bacterial and faecal incubations, however, RS decomposition is impossible without R. bromii.

- Polydextrose is a glucose-derived oligosaccharide. It is composed of glucan with many branches and glycosidic bonds. Some data suggests that it can activate Bifidobacteria, however this has not yet been verified.

4. Other Oligosaccharides

- Some oligosaccharides are derived from pectin, a polysaccharide. This oligosaccharide is referred to as pectic oligosaccharide (POS).

- They are based on the elongation of galacturonic acid or rhamnose (rhamnogalacturonan I). The carboxyl groups can be methyl esterified, and the structure can be acetylated at C2 or C3.

- The side chains are connected to various sugars (such as arabinose, galactose, and xylose) or ferulic acid. Their topologies differ considerably based on the origins of POSs.

5. Non-Carbohydrate Oligosaccharides

- Although carbohydrates are more likely to meet the criteria for prebiotics, there are some compounds, such as cocoa-derived flavanols, that are not classified as carbohydrates but are recommended to be classified as prebiotics. Experiments in vivo and in vitro indicate that flavanols can activate lactic acid bacteria.

Criteria for Eligibility as Prebiotic

To qualify as prebiotic, food items must meet the following criteria:

- Hydrolysis-resistant and nonabsorbable in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

- Selective substrate for one or a few naturally occurring beneficial bacteria in the colon.

- Beneficial to the health of the host and capable of altering the flora to make it healthier.

- Encouraged to flourish or metabolically triggered to create luminal or systemic effects that are advantageous to the health of the host.

- For commercially produced items to have a long shelf life at room temperature, they must be resistant to heat and dehydration.

Mechanism of Action of Prebiotics

- In the human intestine, the absence of enzymes that hydrolyze the polymer bonds of prebiotics permits them to withstand digestion in the small intestine and persist in the gastrointestinal tract.

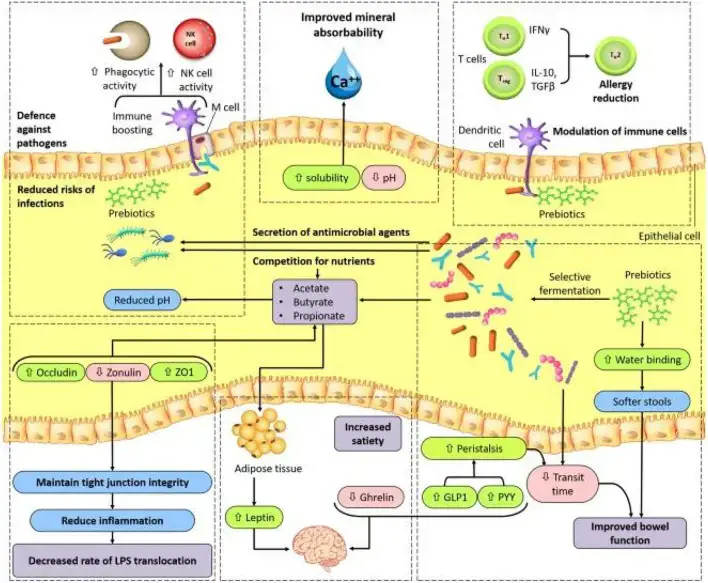

- The human body then transports these prebiotics intact to the large intestine, where they are degraded by the intestinal flora and selectively fermented to produce certain secondary metabolites, which are absorbed by the intestinal epithelium or transported to the liver through the portal vein and can exert beneficial effects on host physiological processes, such as regulating immunity, resisting pathogens, improving intestinal barrier function, and increasin production.

- The most abundant SCFAs in the colon are digested by beneficial bacteria, including acetate, butyrate, and propionate, which are helpful for intestinal and systemic health.

- In addition, the promotion of the growth of certain microbes is a distinct advantage of prebiotics.

- After ingesting specific prebiotics (e.g., inulin, FOS, and GOS), they can stimulate the proliferation of beneficial flora to compete with other species by safeguarding or encouraging the creation of beneficial fermentation products.

- Figure illustrates the potential ways through which prebiotics boost human health.

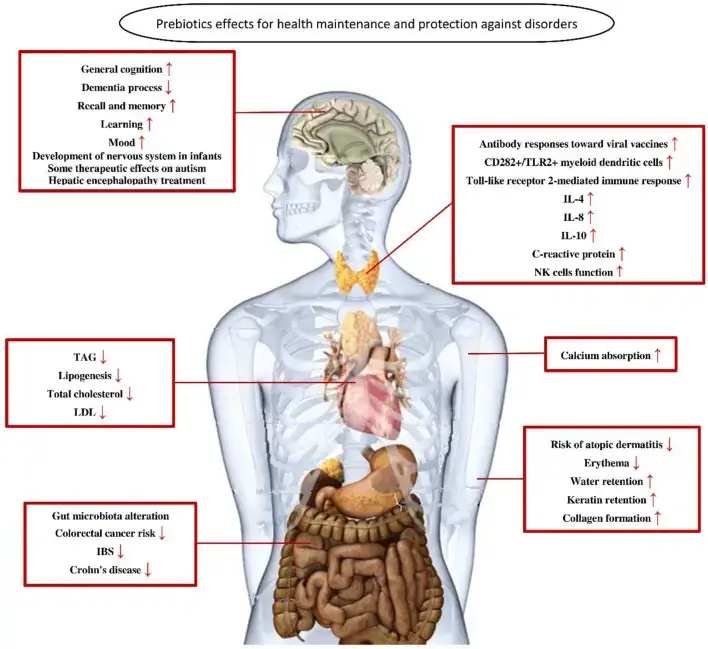

- Additionally, prebiotics have a protective effect not only on the gastrointestinal system but also on other body systems, including the central nervous, immunological, and cardiovascular systems.

Advantages of Prebiotics

Prebiotics provide more health benefits for humans. Several of these benefits are listed below:

- These mostly influence the gastrointestinal tract as well as distant organs such as the central nervous system, immunological system, and cardiovascular system, as their breakdown generates SCFAs that diffuse through gut enterocytes and enter the bloodstream.

- The acidic fermentation product of prebiotics reduces the pH of the gut from 6.5 to 5.5, hence altering the population of gut microorganisms. Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria reduce the number of dangerous bacteria. As an example, the adherence of mannose to Salmonella prevents the colonisation of Salmonella in the epithelium.

- As an increase in Bifidobacteria in the stomach inhibits the activity of spoilage bacteria like Clostridium spp., toxic fermentation products are less likely to form.

- Butyric acid inhibits the growth of lesions such as adenomas and carcinomas in the intestinal epithelium.

- The gut microbiota influences the activity of the central nervous system via the “gut-brain axis.” Certain prebiotics, such as FOS and GOS, modulate synaptic proteins, neurotransmitters (such as d-serine), and brain-derived neurotrophic factors.

Limitations of Prebiotics

There are also some restrictions on the consumption of prebiotics, which are described below.

- Prebiotics may have a deleterious effect on lipid profiles by producing some SCFAs, specifically acetate. Acetate can be converted into acetyl-CoA, a substrate for the production of fatty acids in hepatocytes. This may explain why cholesterol and triglyceride levels increased after rectal acetate infusion.

- Prebiotics undergo fermentation in the colon and exert an osmotic influence on the intestinal lumen. They may result in bloating and gas.

- High doses result in diarrhoea and stomach discomfort.

- Recently, large daily doses have been associated with an increase in gastroesophageal reflux.

References

- De Aguilar-Nascimento, J. E. (2010). Probiotics and Prebiotics. Bioactive Foods in Promoting Health, 171–179. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-374938-3.00012-8

- Davani-Davari D, Negahdaripour M, Karimzadeh I, Seifan M, Mohkam M, Masoumi SJ, Berenjian A, Ghasemi Y. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods. 2019 Mar 9;8(3):92. doi: 10.3390/foods8030092. PMID: 30857316; PMCID: PMC6463098.

- Davani-Davari D, Negahdaripour M, Karimzadeh I, Seifan M, Mohkam M, Masoumi SJ, Berenjian A, Ghasemi Y. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods. 2019; 8(3):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8030092

- You S, Ma Y, Yan B, Pei W, Wu Q, Ding C, Huang C. The promotion mechanism of prebiotics for probiotics: A review. Front Nutr. 2022 Oct 5;9:1000517. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1000517. PMID: 36276830; PMCID: PMC9581195.

- Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017 Mar 4;8(2):172-184. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756. Epub 2017 Feb 6. PMID: 28165863; PMCID: PMC5390821.

- Marteau P, Seksik P. Tolerance of probiotics and prebiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004 Jul;38(6 Suppl):S67-9. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000128929.37156.a7. PMID: 15220662.

- Gibson, G. R., & Roberfroid, M. B. (1995). Dietary Modulation of the Human Colonic Microbiota: Introducing the Concept of Prebiotics. The Journal of Nutrition, 125(6), 1401–1412. doi:10.1093/jn/125.6.1401

- https://atlasbiomed.com/blog/inulin-prebiotic-fiber/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/food-science/prebiotics

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/prebiotics