A PCR machine is a common tool found in labs, especially if you’ve ever dealt with DNA testing or medical diagnostics. At its core, it’s designed to create millions of copies of a specific DNA segment, which sounds simple but is incredibly powerful for tasks like identifying infections, studying genetic mutations, or even solving crimes. The way it works involves cycling through precise temperature changes. First, it heats the sample to split the DNA into two single strands. Then, as it cools, specific primers latch onto the target sequences, marking the spots where new DNA should form. Finally, it warms up again, allowing enzymes to build fresh DNA strands using the originals as templates. This cycle repeats dozens of times, exponentially multiplying the genetic material until there’s enough to analyze. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, these machines became household names because they were crucial for detecting viral RNA in tests. Beyond health crises, they’re used in everything from paternity testing to archaeological research, helping experts trace ancient DNA. What makes it indispensable is its precision and speed—tasks that once took weeks now take hours. While the science behind it is complex, the machine itself is often just a compact box sitting on a lab bench, quietly driving breakthroughs in science and medicine.

What is PCR Machine?

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine, often just called a thermal cycler, is a workhorse in modern labs, especially in fields like genetics, forensics, and medical diagnostics. At its core, it’s designed to make millions or even billions of copies of a specific DNA sequence from a tiny starting sample. This process hinges on temperature cycling—repeatedly heating and cooling samples to trigger DNA unwinding, primer binding, and enzyme-driven replication. By repeating these cycles, even trace amounts of genetic material can be amplified into quantities large enough for analysis, whether for identifying pathogens, sequencing genes, or verifying biological relationships.

The story of PCR machines starts in the 1980s with biochemist Kary Mullis, who conceptualized the technique while working at Cetus Corporation. His eureka moment—using heat-resistant enzymes and temperature shifts to automate DNA copying—earned him a Nobel Prize in 1993. Early iterations were clunky, relying on manual transfers between water baths or rudimentary heating blocks. Lab technicians would physically move samples between baths set to different temperatures—a time-consuming and error-prone process. The breakthrough came with the invention of automated thermal cyclers in the mid-80s, which integrated precise temperature control using Peltier devices or resistive heating. These machines streamlined the process, making PCR faster and more reliable. Over the decades, advancements like real-time PCR (which monitors DNA amplification in real time) and portable models for field use expanded its applications. Today, compact, high-speed PCR devices are ubiquitous, playing a critical role in everything from cancer research to pandemic response, as seen during the COVID-19 crisis. Their evolution mirrors the broader trajectory of molecular biology—transitioning from labor-intensive methods to sleek, automated tools that underpin modern science.

Principle of PCR

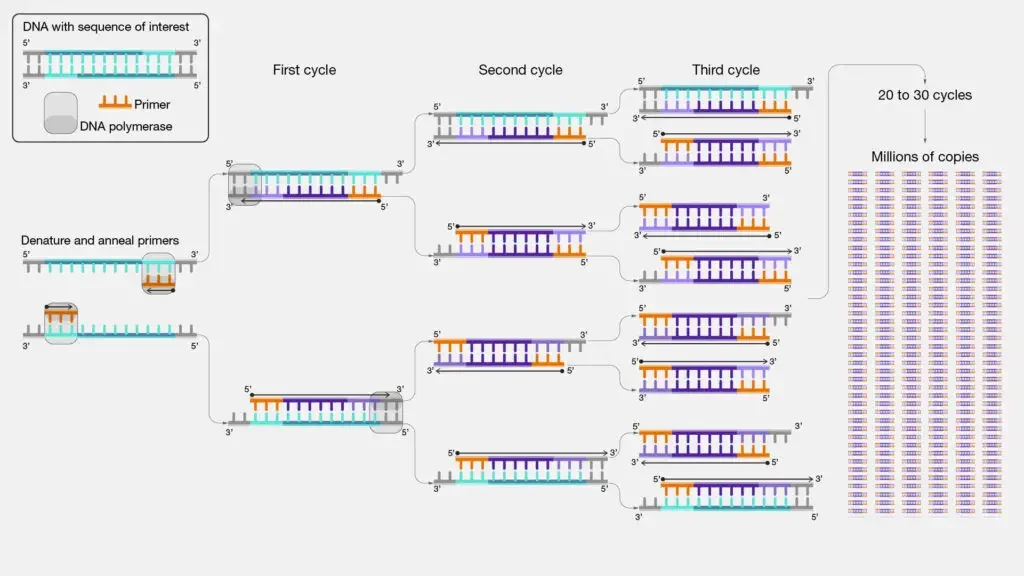

- Developed in the middle of the 1980s by Kary Mullis, PCR is a molecular biology method allowing the exponential amplification of particular DNA sequences from tiny amounts of template DNA.

- Three main phases are driven by cyclic temperature variations in the technique: denaturation, annealing, and elongation

- To break the hydrogen bonds in the denaturation step—usually between 90 and 96°C—the double-stranded DNA is heated, producing single-stranded DNA templates.

- Usually between 50 and 70°C, the reaction temperature is decreased during the annealing phase so that short synthetic oligonucleotide primers may bind particularly to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA.

- Around 72°C, the ideal temperature for DNA polymerase activity, a thermostable enzyme such Taq polymerase adds nucleotides to the 3′ end of every primer, synthesis new complementary DNA strands.

- The number of DNA copies doubles with every cycle, resulting in an exponential rise in the target sequence capable of reaching millions or billions of copies following 25 to 40 cycles.

- By enabling fast, exact, sensitive DNA analysis, PCR transformed genetic research, clinical diagnostics, criminal investigations, and evolutionary biology.

- Its historical significance is highlighted in part by its involvement in the Human Genome Project and Kary Mullis’s 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- Advances like digital PCR and quantitative real-time PCR have increased the applicability of the method by allowing accurate nucleic acid measurement in different samples as well as detection.

- In contemporary molecular biology and allied disciplines, PCR’s combination of simplicity, speed, and sensitivity is still indispensible.

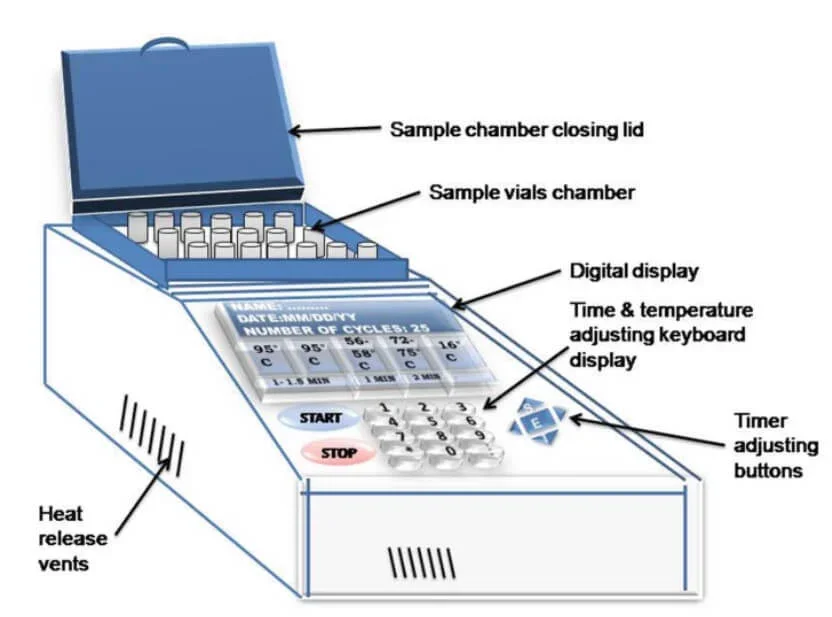

Parts of a PCR Machine

Originally called a thermal cycler, a Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) machine is a laboratory tool meant to precisely control temperature cycles, thereby amplifying DNA segments. Its major elements consist in:

- Thermal Block – Reaction tubes are arranged in wells or holes found in this core section, Thermal Block. For denaturation, annealing, and extension phases of PCR, it is in charge of quick and exact temperature adjustments required.

- Heating and Cooling System – Modern PCR machines frequently have Peltier components, which enable quick heating and cooling by reversing electrical currents, therefore guaranteeing effective temperature cycling.

- Heated Lid – A heated lid presses against the tops of the reaction tubes to avoid condensation on tube lids and preserve reaction volume constancy, therefore negating the requirement for an oil overlay.

- Control Panel and Display – Users program temperature settings, cycle durations, and the number of cycles across this interface—which also offers real-time status updates during the PCR process—control panel and display.

Components/reagents Required for PCR

A good Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) calls for exactly mixed several important reagents:

- DNA Template – The DNA from the sample having the particular area to be amplified.

- DNA Polymerase – An enzyme called DNA polymerase adds nucleotides to the primers to synthesis fresh DNA strands. Derived from Thermus aquaticus, taq polymerase’s heat resistance makes it rather popular.

- Primers – Short, single-stranded DNA sequences complementary to the flanking regions of the target area constitute primers. They offer DNA synthesis’s beginnings.

- Deoxynucleoside Triphosphates (dNTPs) – The building components ( Adenine [dATP], cytosine [dCTP], guanine [dGTP], and thymine [dTTP]) the polymerase combines into the freshly synthesised DNA strand are deoxynucleoside Triphosphates (dNTP).

- Buffer Solution – Maintaining the ideal pH and ionic environment for the functioning of the DNA polymerase, buffer solution

- Divalent Cations – Usually magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), divalent cations are necessary cofactor for enzymatic activity of DNA polymerase.

Steps of PCR – Process of PCR

- First, isolate and purify the template DNA, then add primers, deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), a thermostable DNA polymerase (usually Taq polymerase), and a suitable buffer including divalent cations such Mg²⁺ to produce ideal reaction conditions.

- The denaturation phase starts with heating the reaction mixture to about 94–98°C for 20–30 seconds, so upsetting the hydrogen bonds between the two strands of the double-stranded DNA and producing single-stranded DNA templates fit for primer binding.

- The temperature is rapidly dropped during the annealing step to a range usually between 50–65°C for 20–40 seconds, allowing the short, synthetic primers to bind particularly to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA; the exact temperature is calculated depending on the melting temperature (Tm) of the primers to guarantee specificity and efficiency.

- The temperature is raised to roughly 72°C—the ideal temperature for Taq polymerase activity—where the enzyme synthesizes new DNA strands by adding dNTPs to the 3′ end of each annealed primer; the duration of this step is changed depending on the length of the target sequence, often taking approximately one minute per kilobase of DNA in the extension (or elongation) phase.

- Repeated for 25 to 40 cycles, these three steps—denaturation, annealing, and extension—cause the target DNA segment to be exponentially amplified as each cycle ideally doubles the quantity of DNA copies.

- Usually done at 68–72°C for an extra 5 to 15 minutes, a last extension step guarantees that any missing DNA strands are fully extended and that all products have entirely double-stranded.

- The process ends with a final hold at roughly 4°C, which stabilizes the enhanced DNA until it is extracted for downstream study including quantitative measurements or gel electrophoresisis.

Operating Procedure of PCR Machine

- Check that your reaction tubes are correctly labeled and sealed and that all reagents have been produced, aliquoted, and refrigerated.

- To avoid contamination, arrange the PCR reaction mix in thin-walled PCR tubes in a separate, dedicated space.

- Turn on the thermal cycler and let it run through its self-test and starting sequences.

- Load the reaction tubes into the thermal block such that they line the intended wells or plate holder exactly.

- Program the thermal cycler with the particular cycling settings needed for your experiment including the initial denaturation step, cycling (denaturation, annealing, and extension) parameters, final extension, and final hold temperature.

- Verify that the recommended methodology for your target sequence and enzyme activity matches the programmed temperatures and durations.

- Tighten the heated cover to stop condensation and keep constant reaction volumes during the cycles.

- Start the PCR run and track the display of the machine for fault messages or progress throughout cycles.

- Once the cycling program ends, let the machine automatically keep the reactions at a low temperature—usually 4°C—to stable the produced amplification.

- After removing the PCR tubes from the cycler, straight forwardly take them to a cold storage container or get them ready for downstream analysis, say gel electrophoresisis.

- Turn off the PCR machine, then clean the heat block and accessories as required to stop cross-contamination in next runs.

- To guarantee repeatability and enable troubleshooting if necessary, record all pertinent information about the run, including cycling conditions, reagent lot numbers, and any abnormalities seen.

Types of PCR

Developed into several specialized methods to meet certain research and diagnostic requirements, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is These are some noteworthy categories:

- Multiplex PCR – Using many pairs of primers, multiplex PCR lets various target sequences be simultaneously amplified in a single reaction. For DNA fingerprinting and genetic mutation testing in particular, this method is especially helpful since it lets one effectively analyze several loci.

- Asymmetric PCR – Asymmetric PCR generates single-stranded DNA by amplifying one strand of the target DNA preferentially. Applications like hybridization probing and sequencing where single-stranded products are needed benefit from this approach.

- Nested PCR – By running two sets of primers in consecutive reactions, nested PCR increases specificity. The target area is amplified first by the first set and subsequently by the second set, which binds within the first amplicon. When working with complicated templates especially, this lowers non-specific amplification.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR) – Quantitative PCR, or qPCR, tracks target DNA concentration in real-time throughout amplification. Essential for uses like gene expression analysis and viral load measurement, qPCR lets one quantify DNA by utilizing fluorescent dyes or probes.

- Hot-Start PCR – Reducing non-specific amplification by means of DNA polymerase activity inhibition until the first denaturation stage is finished yields Hot-Start PCR. This is attained by changing the polymerase or reaction configuration, hence increasing yield and specificity.

- Touchdown PCR – Touchdown PCR reduces the annealing temperature during the first cycles, therefore improving yield and specificity. Starting with a higher annealing temperature lowers non-specific binding; whereas, the next lower temperatures enable effective amplification of the target sequence.

- Assembly PCR – Synthesizing lengthy DNA sequences by means of overlapping oligonucleotides, assembly PCR When building big DNA segments without conventional cloning techniques, this method is helpful.

- Colony PCR – Colony PCR looks for desired DNA constructions in bacterial colonies. This approach enables quick identification of clones including the intended insert by explicitly using bacterial colonies as models.

- Digital PCR – Digital PCR divides the PCR reaction into thousands of individual reactions so that target DNA molecules may be absolutely quantified. Highly sensitive, this method finds low-level mutations among other uses needing exact DNA quantification.

- Suicide PCR – In ancient DNA research, suicide PCR is used to minimise false positives by guaranteeing that primers have not been used in the lab before, therefore reducing contamination hazards.

What Is Taq Polymerase?

- Originally obtained from the thermophilic bacteria Thermus aquaticus, which lives in hot springs and other high-temperature habitats, taq polymerase is a thermostable DNA polymerase.

- Its heat resilience makes it necessary for automated DNA amplification since it lets it remain active during the high-temperature denaturation stages of the PCR process.

- By adding deoxynucleotides to a primer coupled to a single-stranded DNA template, the enzyme synthesis new DNA strands, therefore copying the target sequence throughout every cycle of PCR.

- Taq polymerase lacks 3′ to 5′ exonuclease proofreading activity, which causes a rather greater error rate than high-fidelity polymerases even if it is robust and efficient.

- By allowing fast and extensive DNA amplification in PCR, a breakthrough that has had major effects in research, diagnostics, forensic science, and biotechnology, its discovery and use transformed molecular biology.

- Researchers may choose different enzymes with proofreading ability in applications where precision is crucial, although Taq is still extensively utilized because of its simplicity and economy.

- Further extending Taq polymerase’s use range, advances in enzyme engineering have produced modified versions with traits including hot-start capabilities and enhanced processivity.

Applications of PCR

- Directly from patient samples, PCR is extensively applied in clinical diagnostics for fast and sensitive detection of pathogens including viruses, bacteria, and fungi.

- PCR helps DNA fingerprinting and genetic profiling in forensic science, therefore allowing the identification of people from either little or degraded biological evidence.

- Carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis—where certain gene mutations and chromosomal abnormalities are found—are two uses for PCR in genetic testing.

- Gene expression levels are measured using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), therefore offering understanding of cellular activity and disease states.

- Molecular cloning and sequencing depend on PCR since it increases target DNA fragments to levels needed for later Sanger or next-generation sequencing.

- Using PCR, environmental microbiology finds and counts bacterial pollutants in food, soil, and water, therefore guaranteeing safety and regulatory compliance.

- PCR is applied in evolutionary and phylogenetic research to amplify uncommon or ancient DNA sequences, therefore helping to reconstruct evolutionary relationships among species.

- In genotyping and mutation analysis—including SNP identification—PCR is used to examine genetic variation and its consequences for diseases.

- PCR by identifying distinct transgenic sequences allows one to screen agricultural products for genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

- By enabling the amplification and analysis of conserved genetic markers to evaluate biodiversity and community structure, PCR-based methods promote study in microbial ecology.

Advantages of PCR

- By allowing the amplification of minute DNA amounts, PCR makes it possible to examine samples that would otherwise be undetected.

- Crucially for the diagnosis of infections and genetic diseases, the technique has great sensitivity and can identify low-abundance genetic material.

- Often finishing amplification in a few hours, PCR is a fast method that helps clinical diagnosis and research to enable speedy decision making.

- Enough DNA is produced by its exponential amplification mechanism for downstream uses including genotyping, cloning, and sequencing.

- Highly flexible, the method has been modified into many specialized versions like digital PCR for absolute quantification and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for gene expression studies.

- Even with scarce or valuable biological resources, PCR is cost-effective and efficient since it calls for just modest amounts of chemicals and sample.

- By means of thermal cyclers, the automation of PCR improves repeatability and uniformity across trials, therefore supporting consistent results.

- To increase specificity and lower non-specific amplification, PCR can be customized using hot-start and touchdown techniques among other changes.

- Its versatility has let it be included into many areas, including forensics, environmental microbiology, and evolutionary biology, so extending its influence.

- By simplifying research methods and allowing high-throughput analysis, PCR’s capacity to quickly produce vast amounts of target DNA has transformed molecular biology.

Limitations of PCR

- PCR limits its application for the identification of unknown genomic areas since it depends on prior knowledge of the target sequence to design particular primers.

- The technique is quite susceptible to contamination; even little amounts of extraneous DNA can be amplified to provide false-positive findings.

- Standard Taq polymerase does not have proofreading ability, which increases amplification error rate and could cause mutations into the PCR output.

- In complex samples—that is, blood, soil, or food extracts—inhibitory compounds can interfere with enzyme activity and lower amplification efficiency.

- Reagent depletion or poor cycle conditions might affect amplification efficiency and cause a plateau phase whereby no more product is produced.

- High GC-content areas or templates with strong secondary structures might be difficult PCR amplification of which typically calls for modified techniques or specific additives.

- If primers are not ideally designed or if annealing conditions are not tightly regulated, nonspecific amplification and primer-dimers can result.

- Consistent amplification efficiency is the foundation of quantitative PCR tests; deviations might impair the accuracy of quantification, particularly in comparison across several samples.

- Extensive reagent concentration and heat cycling parameter tuning can be time-consuming and vary depending on different templates and experimental configurations.

- PCR is an in vitro method whose utility for some functional research may be limited by its possible inaccuracy in reflecting the in vivo biological milieu.

Precautions using PCR Machine

- To guarantee appropriate heat transfer and avoid sample contamination, only use consumables and tubes suited for PCR.

- To prevent contaminating the reaction setup, wear suitable personal protective gear including gloves, lab coats, and safety goggles.

- Create PCR reactions in a separate, dedicated space free from areas where amplified DNA is handled to lower carryover contamination risk.

- Change pipette tips between each reagent addition to avoid cross-sample contamination; use aerosol-resistant tips.

- Keep all reagents—especially enzymes and dNTPs—on ice throughout setup to maintain their activity and stop early reactions.

- Verify that the heated lid of the thermal cycler is operating as it should help to prevent condensation on tube caps and preserve constant reaction volumes.

- To guarantee correct temperature control and dependable performance, routinely calibrate and maintain the PCR machine per manufacturer’s instructions.

- Every run include appropriate negative and positive controls to check for contamination and confirm the reaction’s effectiveness.

- Steer clear of opening PCR tubes following amplification; if analysis is needed, handle them in a separate post-PCR room to reduce aerosol production.

- Record all PCR settings, reagent lot numbers, and run parameters to guarantee experiment repeatability and help troubleshoot.

FAQ

What is a PCR machine?

A PCR machine, also known as a thermal cycler, is a laboratory instrument used to perform the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique. It allows for the amplification of specific DNA sequences by cycling through different temperature stages.

How does a PCR machine work?

A PCR machine works by cycling through a series of temperature changes to facilitate DNA amplification. It includes stages such as denaturation (separation of DNA strands), annealing (primer binding to the DNA template), and elongation (DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase).

What are the main components of a PCR machine?

The main components of a PCR machine include a heating block with precise temperature control, a lid to cover the reaction vessels, a control panel or interface for programming and monitoring, and a system for temperature regulation and cycling.

What are the temperature ranges typically used in a PCR machine?

The temperature ranges used in a PCR machine can vary depending on the specific PCR protocol. Common temperature ranges include denaturation at around 94-98°C, annealing at 50-68°C, and elongation at 68-72°C.

Can a PCR machine accommodate different sample formats?

Yes, PCR machines are designed to accommodate various sample formats, including PCR tubes, PCR plates, and PCR strips. The machine may have interchangeable blocks or wells to accommodate different sample formats.

How long does a typical PCR run take?

The duration of a PCR run depends on several factors, including the target DNA sequence and the number of cycles required. Generally, a typical PCR run can range from 1 to 3 hours, but more extensive or specialized protocols may require longer run times.

How accurate are PCR machines in temperature control?

PCR machines are designed to provide precise temperature control within a tight range. Advanced PCR machines incorporate temperature control technologies, such as Peltier elements, to achieve accurate and uniform temperature regulation.

Can PCR machines be programmed for specific PCR protocols?

Yes, PCR machines feature programmable interfaces that allow users to set and adjust temperature parameters, cycling times, and other protocol-specific parameters. This flexibility enables customization and optimization of PCR protocols.

How can contamination be prevented in PCR machines?

To prevent contamination in PCR machines, it is crucial to follow good laboratory practices. This includes using sterile techniques, working in a clean and dedicated PCR workspace, regularly cleaning the machine and accessories, and implementing proper waste disposal protocols.

Can PCR machines be connected to a computer or network?

Many modern PCR machines have connectivity options, such as USB or Ethernet ports, enabling them to be connected to computers or networks. This connectivity allows for data transfer, remote monitoring, and control of the PCR machine, enhancing convenience and efficiency in the laboratory.

- Mullis, K., & Faloona, F. (1987). Specific synthesis of DNA in vitro via a polymerase-catalyzed chain reaction. Methods in Enzymology, 155, 335-350.

- Saiki, R. K., Scharf, S., Faloona, F., Mullis, K. B., Horn, G. T., Erlich, H. A., & Arnheim, N. (1985). Enzymatic amplification of β-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science, 230(4732), 1350-1354.

- Bustin, S. A., Benes, V., Garson, J. A., Hellemans, J., Huggett, J., Kubista, M., … & Wittwer, C. T. (2009). The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clinical Chemistry, 55(4), 611-622.

- Dieffenbach, C. W., Lowe, T. M., & Dveksler, G. S. (eds.). (2013). General principles of PCR. PCR primer: a laboratory manual (2nd ed.). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Rychlik, W., & Rhoads, R. E. (1989). A computer program for choosing optimal oligonucleotides for filter hybridization, sequencing and in vitro amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 17(21), 8543-8551.

- Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J., & White, T. J. (eds.). (2012). PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press.

- Text Highlighting: Select any text in the post content to highlight it

- Text Annotation: Select text and add comments with annotations

- Comment Management: Edit or delete your own comments

- Highlight Management: Remove your own highlights

How to use: Simply select any text in the post content above, and you'll see annotation options. Login here or create an account to get started.