- Parental care in amphibians refers to the behavior exhibited by a parent toward its offspring, aimed at enhancing the offspring’s survival chances until they can independently defend themselves from environmental hazards and predators. Although amphibians were traditionally considered to display minimal parental care compared to birds and mammals, recent studies have uncovered a surprising range of behaviors that contradict this assumption. In fact, amphibians show a variety of parental care strategies that can significantly impact offspring survival rates.

- Parental care in amphibians can be broadly classified into two categories: protection by nests, nurseries, or shelters, and direct care by parents. These strategies represent a diverse spectrum of behaviors that amphibians use to safeguard their young, highlighting the complexity of amphibian reproductive strategies. Protection through nests or shelters involves creating safe environments where eggs and larvae can develop without significant risk from predators, while direct care encompasses activities where parents are actively engaged with their offspring, such as carrying or feeding them.

- Among amphibians, parental care is more pronounced in anurans (frogs and toads) than in urodeles (salamanders) or apodans (caecilians). This distinction is likely due to the different life histories and reproductive strategies employed by these groups. For instance, many anurans exhibit behaviors such as transporting eggs to moist environments, guarding nests, or even carrying larvae on their backs. In contrast, urodeles and apodans, which typically have different reproductive cycles and environmental needs, exhibit less parental involvement.

- The role of parental care in amphibians is crucial because it directly impacts the survival rate of offspring. By increasing the offspring’s chances of surviving until they reach independence, parental care ensures the continuation of the species. However, it is important to note that this investment in offspring can also reduce a parent’s ability to reproduce again in the short term. This trade-off between current and future reproductive success is a central consideration in the evolution of parental care in amphibians.

- In addition to egg attendance and protection, some amphibians engage in more complex behaviors such as egg transportation or feeding of larvae. For example, certain species of frogs and toads may transport their eggs to safer, more favorable environments, such as temporary pools or humid microhabitats. This reduces the risk of desiccation and predation, particularly in species where the eggs are vulnerable to environmental fluctuations. In other cases, some amphibians, particularly species with aquatic larvae, may actively feed their offspring or help them navigate the hazards of their environment.

Parental Care in Amphibia

1. Protection by Nests, Nurseries, or Shelters in Amphibians

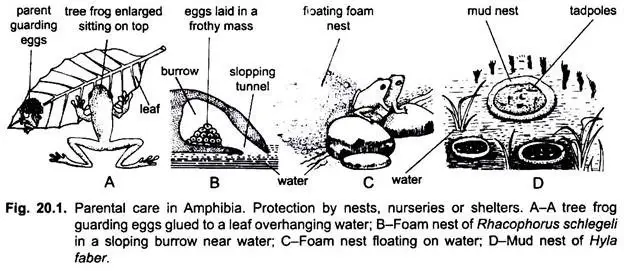

Amphibians have evolved a variety of innovative strategies to protect their vulnerable eggs and larvae from predation. These methods often involve creating safe microhabitats that shield offspring until they are capable of defending themselves. The protection by nests, nurseries, or shelters can be classified into several distinct types, depending on the species and their respective habitats. Below is an in-depth look at the various mechanisms amphibians use to safeguard their offspring.

- Site Selection:

Many amphibians, particularly tropical frogs and toads, lay their eggs in moist, protected microhabitats on land, close to water bodies. For instance, certain tree frogs, like those from the genera Phyllomedusa, Rhacophorus, and Hylodes, attach their eggs to the leaves or branches that overhang water. This method not only protects the eggs from aquatic predators but also ensures that the tadpoles can drop into the water below after hatching, where they complete their metamorphosis. Similarly, in tropical regions, some frogs lay eggs in water collected in epiphytic plants, where the developing tadpoles are safe from most aquatic predators. - Defending Eggs and Territories:

In certain species of frogs, such as Rana clamitans (the green frog), males are highly territorial and actively defend their egg-laying sites. These frogs may attack small intruders to prevent disturbance of their eggs. In some cases, the male or female will guard the eggs directly. For example, in Mantophryne robusta, the male sits directly over the eggs, holding the gelatinous envelope in place with his hands to protect them. Removal of these guarding frogs can lead to egg desiccation or predation, underscoring the critical role of parental vigilance. - Direct Development:

Some amphibians, such as certain species of tree frogs (Eleutherodactylus, Hylodes, and Hyla nebulosa), avoid larval mortality by bypassing the tadpole stage altogether. The eggs in these species hatch directly into miniature frogs, thus eliminating the risks faced by larvae in aquatic environments. Similarly, the red-backed salamander (Plethodon cinereus) produces hatchlings that are already miniatures of the adult, negating the need for a separate aquatic larval stage. - Foam Nests:

Several amphibians use foam nests to provide protection for their eggs. For example, the Japanese tree frog (Rhacophorus schlegelii) constructs a frothy mass of mucus, which serves as both a nest and a protective barrier. The female produces the mucus and forms it into a foam into which the eggs are laid. After hatching, the tadpoles are washed down a sloping tunnel created by the mating pair, leading them to a water source for further development. Similar foam nest behaviors are observed in Leptodactylus mystacinus (South American tree frog), where the female creates a frothy mass of mucus in which the eggs are deposited, allowing the tadpoles to easily enter water upon hatching. Some other anuran species also use large amounts of mucus to create foam nests, providing a safe space for the eggs and allowing tadpoles to drop into water once they hatch. - Mud Nests:

In Brazil, the tree frog Hyla faber builds a mud nest or nursery in shallow water on the edge of a pond. The female scoops out mud to form a circular wall that protects the eggs and early larvae from predators such as insects and fish. The walls of the nest help prevent the eggs from being disturbed, and once the larvae are large enough, they are able to leave the nest. Heavy rains eventually break down the wall, allowing the young to move into the water for further development. - Tree Nests:

Some tree frogs, such as Phyllomedusa hypochondrales in South America and Rhacophorus malabaricus in India, attach their eggs to the foliage hanging over water. Once the tadpoles hatch, they drop directly into the water, where they can complete their metamorphosis. In Hyla resinfictrix, another tree frog species, the eggs are laid in a cavity lined with beeswax. This cavity is filled with rainwater, providing a safe environment for the developing tadpoles. - Gelatinous Bags:

Certain amphibians, such as Phrynixalus biroi, enclose their eggs in transparent, gelatinous sacs. These sacs serve as protective coverings, safeguarding the eggs from external threats. The gelatinous bags allow the eggs to develop safely in mountain streams, where the young eventually emerge as fully formed frogs. Similarly, Salamandrella keyserlingi, a small aquatic salamander, deposits its eggs in a gelatinous bag attached to an aquatic plant. This protective bag shields the eggs from predators and environmental dangers. - Protection on Trees or in Moss:

Several species of frogs from the genus Hylodes, found in tropical America, lay their eggs in damp places away from water, such as under stones, moss, or plant leaves. The development is accelerated within the egg, and the offspring emerge as air-breathing frogs, bypassing the larval stage altogether. The large amount of yolk in the eggs enables the entire developmental process to occur within the egg, ensuring a safe environment for the young frogs until they are ready to leave their nests.

2. Direct Carrying by Parents in Amphibians

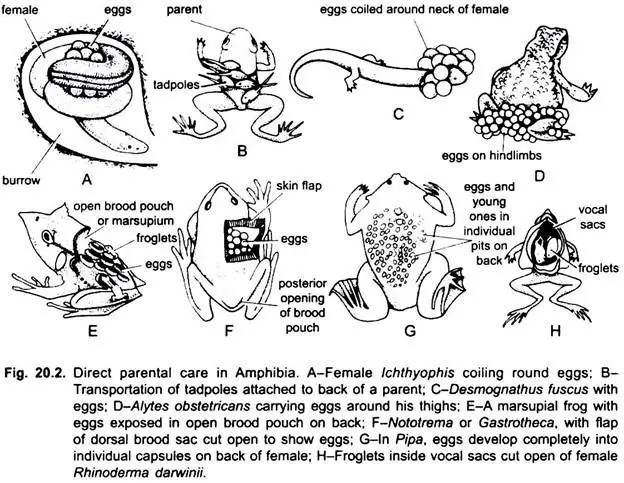

In amphibians, a variety of parental care strategies are employed to protect and nurture offspring, especially during their early developmental stages. Among these strategies, direct carrying by parents involves the transportation or protection of eggs and tadpoles by one or both parents. This method of care ensures that offspring are safeguarded from environmental hazards and predators while developing into more independent stages. Below is an overview of the different forms of direct carrying observed in amphibians:

- Coiling Around Eggs:

Some amphibians, such as the Congo eel (Amphiuma) and certain caecilians like Ichthyophis and Hypogeophis, employ a strategy where the female lays large eggs in burrows within damp soil. After depositing the eggs, the female coils her body around them, protecting them until they hatch. This behavior ensures that the eggs remain shielded from external threats and prevents desiccation in the soil. By physically wrapping around the eggs, the female keeps the developing embryos safe from predators and maintains moisture in the environment. - Transferring Tadpoles to Water:

Certain small frog species, such as Phyllobates and Dendrobates in tropical Africa and South America, exhibit a remarkable form of parental care. After laying eggs on the ground, the hatching tadpoles attach themselves to the back of one of the parents using a sucker-like mouth. The parent then carries the tadpoles to water, where they can complete their development. This method ensures that the tadpoles are transported to a safe aquatic environment, where they can continue to grow and undergo metamorphosis. - Eggs Glued to the Body:

In some amphibian species, instead of remaining with the eggs, the female carries them attached to her body. For instance, in the dusky salamander (Desmognathus fuscus), the female carries a string of eggs coiled around her neck until they hatch. Similarly, in the Sri Lankan tree frog (Rhacophorus reticulatus), the eggs are glued to the female’s belly. Another fascinating example is the European midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans), where the male entangles the eggs around his hind legs. He carries the eggs with him until they are ready to hatch, at which point he releases the tadpoles into nearby water. - Eggs in Back Pouches:

In a unique group of amphibians known as marsupial frogs or toads, the female carries the eggs on her back. This can be done in an open oval depression, a closed pouch, or individual pockets. In the Brazilian tree toad (Hyla goeldii or Cryptobatrachus evansi), the female’s posterior back forms a brood pouch, where the eggs remain exposed but are still safeguarded. The developing eggs eventually mature into miniature frogs, which then leave their mother’s back once fully formed. - Organs as Brooding Pouches:

In certain amphibians, the parent carries developing eggs or larvae in specialized body structures that serve as brooding pouches. For instance, the male of the South American Darwin’s frog (Rhinoderma darwinii) carries at least two fertilized eggs in his vocal sacs. These sacs provide a protected environment where the eggs undergo complete development, emerging as fully formed froglets. In the West African tree frog (Hylambates breviceps), the female carries eggs in her buccal cavity. Additionally, in the genus Arthmleptis, it is the male that keeps the larvae in his mouth for protection. The Australian frog Rheobatrachus silus exhibits a rare form of gastric incubation, where the female carries eggs in her stomach. After the tadpoles undergo metamorphosis, they are expelled from the mother’s mouth as fully developed frogs. - Viviparity:

Some amphibians have evolved a form of reproduction known as ovoviviparity, where eggs are retained within the female’s body until the offspring are fully developed. The African toads Nectophrynoides and Pseudophryne give birth to live, fully formed young frogs. Similarly, the European salamander (Salamandra salamandra) produces 20 or more small young, while the Alpine salamander (S. atra) gives birth to one or two fully developed offspring. This method ensures the young are born in a more developed, less vulnerable state, reducing their exposure to predation and environmental risks.

- https://www.studocu.com/in/document/mahatma-jyotiba-phule-rohilkhand-university/development-biology-and-animal-behavior/parental-care-in-amphibians/43206910

- http://www.lscollege.ac.in/sites/default/files/e-content/parental%20care%20in%20amphibia.pdf

- https://elearning.raghunathpurcollege.ac.in/files/8E649F5115966051820.pdf

- https://www.iaszoology.com/parental-care/

- https://www.notesonzoology.com/amphibia/parental-care-in-amphibia-with-diagram-vertebrates-chordata-zoology/8249

- https://biozoomer.com/2011/11/parental-care-amphibians.html

- https://content.patnawomenscollege.in/zoology/Zoo%20CC305%20Parental%20Care%20in%20Amphibians.pdf

- https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/parental-care-in-amphibians-130592667/130592667

- https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/parental-care-in-amphibia-240068352/240068352

- https://dacollege.org/uploads/stdmat/zoo-sem3-hons-PARENTAL-CATRE-OF-Amphibia.pdf

- https://www.srapcollege.co.in/sites/default/files/Parental%20Care%20in%20Amphibia.pdf

- Text Highlighting: Select any text in the post content to highlight it

- Text Annotation: Select text and add comments with annotations

- Comment Management: Edit or delete your own comments

- Highlight Management: Remove your own highlights

How to use: Simply select any text in the post content above, and you'll see annotation options. Login here or create an account to get started.