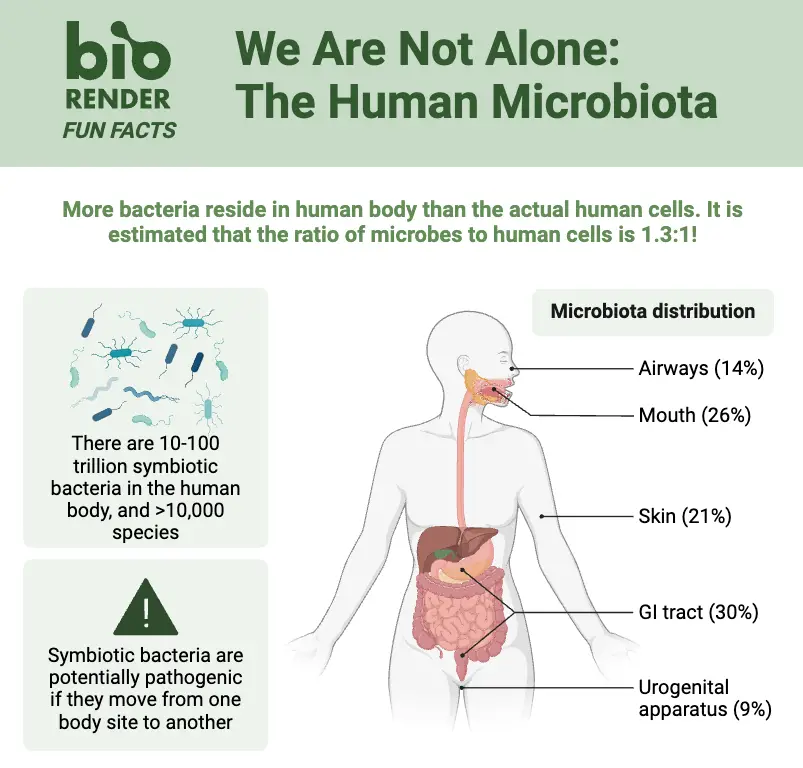

The human body is home to trillions of tiny organisms, like bacteria, fungi, and viruses, that live on the skin, in the mouth, gut, and other areas. This community of microbes is called the human microbiome. Most of these organisms aren’t harmful—in fact, many are essential for health. They help digest food, produce vitamins, and even train the immune system to recognize threats. The term normal flora (or resident microbiota) specifically refers to the microbes that typically live in or on the body without causing problems. Think of them as long-term residents that stick around, unlike temporary microbes that come and go.

These helpful microbes vary depending on body location. For example, the gut hosts bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium that aid digestion, while the skin has species like Staphylococcus epidermidis that protect against harmful invaders. Even the mouth and nose have their own unique mixes. Factors like diet, age, and environment shape which microbes thrive. Though usually harmless, they can sometimes cause issues if they grow out of balance or spread to places they shouldn’t—like when gut bacteria enter the bloodstream due to injury.

The relationship between humans and their microbiome is mostly mutual. The body provides a place to live, and microbes return the favor by crowding out pathogens, breaking down toxins, or calming inflammation. Research keeps uncovering new ways these tiny partners influence everything from mood to disease risk. While “normal flora” once referred only to bacteria, modern science recognizes the microbiome as a diverse, dynamic ecosystem that’s as unique as a fingerprint.

What is Human Microbiome OR Normal Flora Of The Human Body?

- Often referred to as the normal flora, the human microbiome is the whole population of microorganisms—including bacteria, archaea, fungus, viruses, and even protozoa—that occupy different parts of the human body from birth until death.

- Originally known as “normal flora,” this microbial community was later classified as “microbiota,” the living entities, and “microbiome,” the aggregate genomes and functional activities of which emphasise both composition and activity.

- Each having its own unique collection of microbial occupants suited to local environmental circumstances, these bacteria occupy different anatomical areas including the skin, mouth cavity, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, and urogenital system.

- Through fermentation of undigested carbohydrates, synthesis of vital vitamins (e.g., vitamin K and several B vitamins), and contribution to the metabolism of food and xenobiotic substances, the microbiome is crucially important in human physiology.

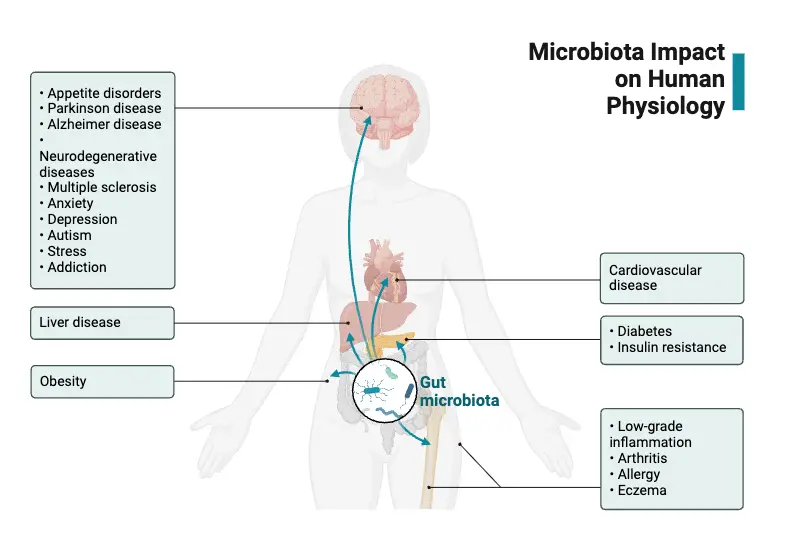

- Apart from its metabolic purposes, the microbiome is essential for the immune system’s growth and control, improves barrier properties, alters inflammatory reactions, and provides defence against pathogenic invasion via competitive exclusion.

- While later studies by Koch and others concentrated on pathogens, historical notes by pioneers like Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in the 17th century first revealed the existence of microbial life; modern approaches have shifted attention to the beneficial and symbiotic roles of most of these microorganisms.

- Early in the 2000s, the Human Microbiome Project launched a significant paradigm change by using metagenomics and culture-independent methods like 16S rRNA gene sequencing to expose the great variety and dynamic interactions of microbial populations throughout many body locations.

- Underlining the microbiome’s importance as a major contributor to general health, current research ties dysbiosis—or imbalance in the microbiome—to several health issues, including inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, metabolic disorders, and even neurological diseases.

- Emphasising its potential as a “forgotten organ” essential for preserving homeostasis and avoiding illness, continuous research investigates how modification of the microbiota might lead to new treatment tactics and individualised medical interventions.

Types of Normal Flora in Human Body

There are present 2 types of Normal Flora in Human Body:

- Resident Flora: These bacteria are continuously found in certain anatomical locations throughout the human body. They help to preserve health and build a steady, long-term relationship with the host. Escherichia coli, for instance, lives in the colon and helps break down food and synthesis vitamin K.

- Transient Flora: These bacteria, which usually come from the surroundings, live in the body for a short time. They can comprise both non-pathogenic and maybe harmful bacteria and do not live permanently on the host. For example, some strains of Staphylococcus might be present on the skin momentarily without doing damage.

Characteristics of the Normal Flora

- Every anatomical site—including the skin, mouth cavity, respiratory system, gastrointestinal tract, and urogenital tract—where normal flora is prevalent has a distinct microbial population.

- Highly suited to the particular environmental circumstances of their niches, microorganisms in the typical flora vary in temperature, moisture, pH, and nutrient availability.

- Their mutually beneficial interaction with the host helps with important processes like digesting, vitamin synthesis—for instance, vitamin K in the gut—and immune response control.

- By means of competition for resources and the release of antimicrobial chemicals, resident microbes help to prevent the colonization of harmful species, hence promoting competitive exclusion.

- Normal flora’s composition is kept in a dynamic balance that host elements like age, food, hormonal fluctuations, immunological state, and environmental exposures can affect.

- Hosts and their microbial communities have long-standing evolutionary co-adaptation that generates synergistic interactions improving general health.

- Changes in personal cleanliness habits and the use of antibiotics among other external elements might upset the equilibrium of the natural flora, therefore causing dysbiosis and maybe increasing susceptibility to diseases.

Origin of Microbiota in human Body

- Originally ancient, the human microbiota co-evolves with our species over millions of years and is essential in determining our physiology and immune system.

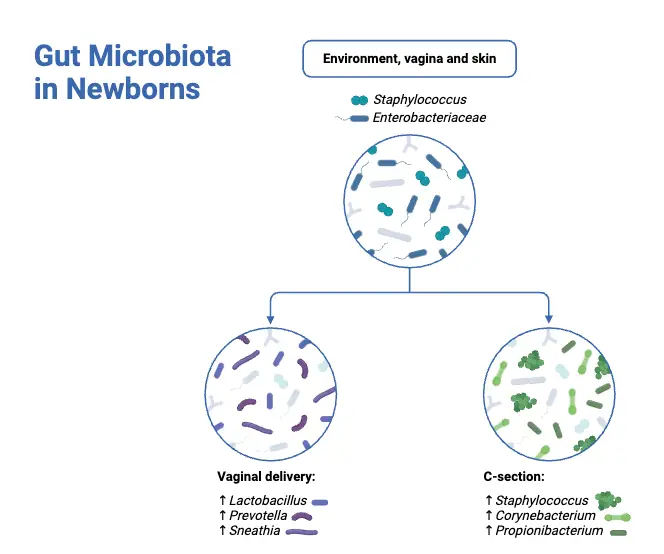

- Beginning throughout the birthing process, first microbial colonization occurs during delivery when newborns pick up germs from the mother’s vaginal and fecal flora in vaginal births or from the mother’s skin and surroundings in cesarean sections.

- Early microbial exposure persists through nursing, intimate physical contact, and environmental interactions to build the basic gut, skin, oral cavity, and respiratory tract flora.

- The human body and its bacteria have evolved in a symbiotic connection whereby microorganisms provide vital activities including vitamin production, nutrition metabolism, and pathogen prevention.

- By increasing flexibility, horizontal gene transfer across microbial populations has let these species react to environmental changes and host nutritional or immunological changes over time.

- While a core microbiota is common across people, modern studies employing high-throughput sequencing have shown that differences occur from elements like genetics, lifestyle, nutrition, geographic location, and antibiotic or pathogen exposure.

Normal Microbiota of the Skin

- Comprising the biggest organ in the human body, the skin is colonised by a varied and complex collection of microorganisms ranging from bacteria to fungus to viruses and minute arthropods.

- With frequent species including Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Cutibacterium, the main bacterial phyla on the skin include Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes.

- Whereas moist areas usually show a greater prevalence of Corynebacterium and certain Staphylococcus species, in sebaceous (oily) areas the bacteria is usually dominated by Cutibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus species.

- Often reflecting a combination of ambient and host-derived microorganisms, dry skin locations show more variety of bacterial species and are less densely colonised.

- Often called the mycobiome, the fungus population on the skin is mostly made of Malassezia species, which help to preserve skin homeostasis.

- By competing with possible pathogens, generating antimicrobial compounds, and adjusting local immune responses, these microbial populations help the skin to maintain its barrier capacity.

- Anatomical location, environmental variables (such as humidity and temperature), host genetics, and lifestyle choices like hygienic practices and cosmetic usage all affect the makeup of the skin microbiota.

- Numerous dermatological disorders, including acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis, have been linked to changes or imbalances in the natural skin flora (dysbiosis).

- Developments in culture-independent methods, including 16S rRNA gene sequencing, have given thorough insights on the composition and dynamics of the skin microbiota, thereby improving our knowledge of its function in health and illness.

- Developing focused treatments and preventative actions meant to preserve or restore microbial balance and general skin health depends on an awareness of the relevance of the skin microbiome.

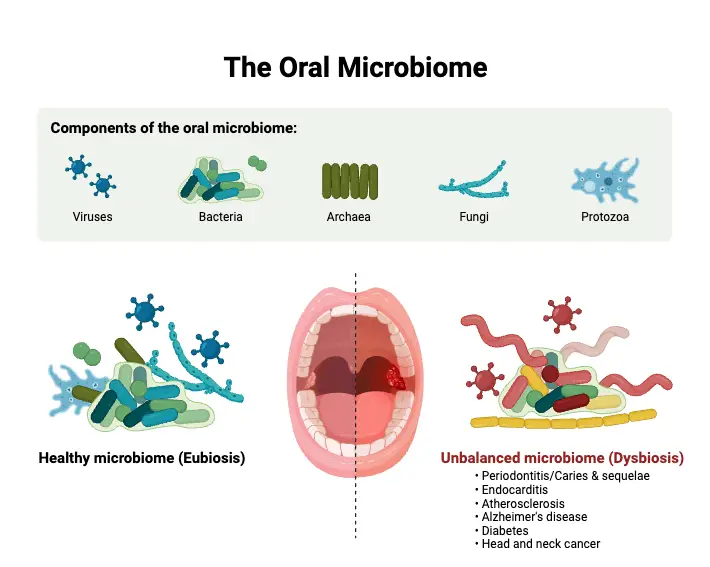

Normal Microbiota of Mouth

- Microorganisms including bacteria, fungus, viruses, and protozoa abound in the dynamic and sophisticated community housed in the mouth cavity.

- Key for biofilm development on dental surfaces, the tongue, and oral mucosa, many Streptococcus species—including S. salivarius, S. sanguis, S. mutans, and S. pneumoniae—are found in predominance among bacterial occupants.

- Important roles in the metabolic digestion of dietary carbohydrates and the development of dental plaque are played by Anaerobic bacteria including Actinomyces, Veillonella, Fusobacterium, and Prevotella species.

- Saliva is a vital medium that provides nutrients, controls pH, helps microbial biofilms to be distributed and matured, therefore affecting the oral microbial makeup.

- Candida albicans is a commensal organism that can turn opportunistic in immunocompromised conditions, therefore mostly reflecting fungal colonisation.

- Usually present in low abundances, protozoa such Trichomonas tenax and Entamoeba gingivalis can be found using sophisticated molecular techniques.

- By inducing local immune responses and generating antimicrobial agents that help control pathogenic organisms, the oral bacteria helps to preserve mucosal immunity.

- Variations in microbial communities are affected by elements like nutrition, dental hygiene, age, and systemic health, thereby stressing the need of microbial balance for both oral and general health.

- Metagenomics and 16S rRNA gene sequencing among other culture-independent methods have tremendously improved our knowledge of the variety, dynamics, and functional possibilities of the oral microbiome.

Normal Microbiota of Ear

- Particularly in the external auditory canal, the natural flora of the ear consists in a balanced population of fungus and bacteria living without producing illness.

- Reflecting the parallels between ear skin and other body surfaces, prevalent bacterial genera are Corynebacterium, Cutibacterium, and Staphylococcus (especially S. epidermidis and S. auricularis).

- Usually representing temporary or low-level invaders, gram-negative bacteria such Pseudomonas and Moraxella may be found at reduced abundances.

- Through its acidic pH and antibacterial components, earwax (cerumen) both physically exels waste through epithelial movement and chemically inhibits microbial multiplication.

- Although Candida and Penicillium species can also be found, the fungal component of the ear microbiome is usually less varied; Malassezia species are the most often discovered.

- A single nucleotide variation in the ABCC11 gene genetically determines the kind of earwax—wet or dry—which alters the surrounding microenvironment and could hence change microbial makeup.

- Techniques independent of culture, including 16S rRNA gene sequencing, often show that the ear canal microbiota is somewhat similar to the cutaneous flora but is specifically suited to the particular anatomical and biochemical environment of the ear.

- Maintaining a healthy ear microbiome is crucial as dysbiosis has been related to conditions like otitis externa, in which an imbalance of the microbial balance can make people prone to infections.

- Opportunistic pathogens, which under conditions of compromised barrier function or changed local immunity can cause middle ear infections, may find a reservoir in the ear microbiota.

- Further clarification of the typical microbial makeup of the ear and its consequences for ear health and disease treatment depends on constant study employing sophisticated sequencing and culture-based techniques.

Normal flora of Stomach

- Because of its very acidic environment, the stomach was previously thought to be sterile; yet, contemporary molecular methods have shown that even in healthy people a low-biomass microbial population occurs.

- With only acid-tolerant and transitory bacteria able to survive, the general microbial diversity is lower in the severe stomach pH than in other sections of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Common bacterial species found in the stomach in those without Helicobacter pylori infection are Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Veillonella, which are presumably sourced from the oral cavity.

- Though many carriers remain asymptomatic, Helicobacter pylori can dominate the stomach microbiota and is intimately associated with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and a higher risk of gastric cancer.

- Diet, usage of acid-suppressing drugs (e.g., proton pump inhibitors), and host genetics might affect the makeup of the stomach microbiota, hence generating inter-individual diversity.

- The natural gastric flora is thought to be important in preserving mucosal barrier integrity and adjusting local immune responses, therefore shielding the stomach lining from pathogen colonization.

- Identification of these low-abundance microbial communities and advancement of our knowledge of the stomach environment have been much aided by culture-independent techniques such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

- Clarifying the function of the normal microbiota of the stomach in gastrointestinal health and illness depends on ongoing study on it; so, more focused treatments for diseases such gastritis and peptic ulcer disease might result.

Normal flora of Small Intestine and Large Intestine

- Because of its greater acidity, shorter transit time, and bile salts and digestive enzymes, the small intestine has a somewhat low-biomass, active microbial habitat compared to the colon.

- Common facultative anaerobes in the proximal small intestine include Streptococci, Lactobacilli, and Enterobacteriaceae suggest ongoing flow from the oral cavity.

- Though general diversity remains minimal, the distal small intestine displays a rise in anaerobic bacteria including members of the Veillonellaceae and Clostridiales.

- With bacterial counts ranging from 10^11 to 10^12 cells per gram of material, the large intestine (colon) boasts the densest and most varied microbial population in the human body.

- Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the dominant phyla in the colon; important genera like Bacteroides, Prevotella, Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, and Clostridium help to ferment complex carbohydrates.

- Dietary fibers are broken down into short-chain fatty acids (e.g., butyrate, acetate, and propionate), which colonocytes use for energy and alter host immunological responses via means of the colonic microbiota.

- Apart from bacteria, the large intestine supports archaea (e.g., Methanobrevibacter smithii), fungus, and viruses that collectively help to maintain a healthy intestinal ecology.

- Small and large intestine microbiota composition and function are much influenced by factors including food, age, antibiotic usage, and host genetics, thereby influencing gastrointestinal and general health.

Normal flora of the Respiratory Tract

- Upper, middle, and lower sections of the respiratory tract each have unique structural and physiological characteristics that affect microbial colonising ability.

- Few species include Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Peptostreptococcus, and Fusobacterium occupy the nares (anterior and posterior) in the upper airways.

- With other Gram-negative coccobacilli including Moraxella catarrhalis and Kingella species, and noncapsulated Haemophilus influenzae also present, the nasopharynx hosts a more complicated community dominated by streptococci (including S. salivarius, S. parasanguis, and S. pneumoniae).

- The middle airways—including the oropharynx and tonsils—are defined by a mix of ecosystems where Gram-positive and Gram-negative cocci predominate; anaerobes exceed aerobes by around 100:1.

- While aerobic bacteria like Streptococcus and Neisseria are also often retrieved, over 20% of people carry Staphylococcus aureus in this region; common anaerobic bacteria in the oropharynx include Peptostreptococcus, Veillonella, Actinomyces, and Fusobacterium.

- Along with Gram-negative genera including Neisseria, Moraxella, Kingella, Cardiobacterium, and Eikenella, additional Gram-positive cocci including Stomatococcus mucilaginosus and Gemella species add to the oropharyngeal flora; Haemophilus species, primarily noncapsulated strains, are rare.

- Along with other Gram-positive bacilli such Corynebacterium, Eubacterium, Lactobacillus, Propionibacterium, and Rothia, the oropharynx also boasts a significant population of Actinomyces, which colonise many surfaces via fimbriae and extracellular polysaccharides.

- With Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax as the only protozoa, fungal colonisation is mostly limited to yeasts like Candida albicans; predominant anaerobes in the oropharynx also include Fusobacterium (with Fusobacterium nucleatum most common).

- Microbial colonisation is usually temporary and sparse in the lower airways, which comprise the larynx, trachea, bronchi, and lungs; only under situations wherein the ciliated epithelium is injured or changed by illness can sustained colonisation result.

Normal Microbiota of the Intestinal Tract

- All of the very varied microbial species found in the intestinal tract—including viruses, bacteria, archaea, and fungi—have important functions in host physiology.

- With estimates ranging from 10^13 to 10^14 cells, microbial density in the colon is rather high—mostly composed of two major bacterial phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, together with considerable numbers of Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia.

- Because of things like fast transit time, greater oxygen levels, and acidic conditions, the small intestine has a reduced microbial burden; here, facultative anaerobes like Lactobacillus and Streptococcus species are more abundant.

- By digesting undigested carbohydrates and dietary fibres into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are vital energy sources for colonocytes and help to maintain metabolic balance, intestinal bacteria help to digest food.

- These bacteria help the absorption of minerals, therefore improving general nutritional condition by synthesising essential vitamins like vitamin K and other B vitamins.

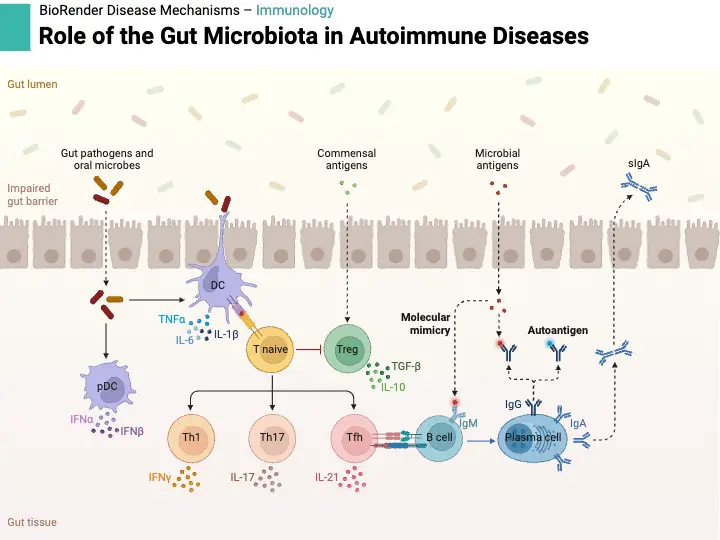

- Key in the development and control of the immune system, the gut flora supports the growth of gut-associated lymphoid tissue, increases secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA), and helps preserve immunological tolerance while fighting against diseases.

- Early life usually results in a very stable core microbiota; nevertheless, environmental exposures, genetics, nutrition, and antibiotic usage all affect inter-individual variability.

- From inflammatory bowel disease to obesity to metabolic syndrome to even changes in neurobehavioral processes via the gut-brain axis, disruptions in the normal intestinal flora, also referred to as dysbiosis, have been related to a variety of health disorders.

Normal Microbiota of the Urethra

- Long thought to be sterile by traditional culture techniques, the urethra is now known to have a limited but unique population of bacteria promoting urogenital health.

- Using culture-independent methods like 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the typical urethral flora has been shown to be mostly constituted of bacteria, including species often found on the skin and surrounding mucosal surfaces.

- Studies have shown organisms including Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, and many Streptococcus species as common residents of the distal urethral in men, most likely from the external genitalia and skin.

- With frequent species including Lactobacillus, Corynebacterium, and Streptococcus, the urethral flora in women typically overlaps with the vaginal microbiota, therefore contributing to a microenvironment that helps preserve local immunological balance and guard against infections.

- Factors include hormonal state, sexual activity, hygienic practices, and age can affect the composition and density of the urethral microbiota, hence determining the microbial ecology of the lower urinary tract.

- Reducing the colonisation of uropathogens by a balanced urethral microbiota is supposed to help to lower the incidence of urinary tract infections and other urological problems.

- As well as the possibility for focused microbiome-based treatments in controlling urinary health, current research keeps investigating the functional relationships between these indigenous bacteria and the immune system of the host.

Normal Microbiota of the Vagina

- Lactobacillus species predominate in the vaginal environment; they produce lactic acid, which helps to maintain a low pH and hence stop the spread of harmful bacteria.

- Common lactobacilli that help to create a barrier against infections are Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus iners, Lactobacillus jensenii, and Lactobacillus gasseri.

- Although transitory colonisers including Gardnerella vaginalis or Atopobium vaginae can be found in smaller abundances, the prevalence of lactobacilli in a healthy condition reduces the occurrence of anaerobic bacteria that can cause bacterial vaginosis.

- By maintaining mucosal immunity, avoiding infections, and lowering the risk of sexually transmitted illnesses, the vaginal flora is very important for reproductive health.

- The balance of the vaginal bacteria can be changed by factors like hormonal changes, the menstrual cycle, sexual activity, antibiotic usage, and personal cleanliness; occasionally this results in dysbiosis.

- Although early microbiological research was predicated on culture techniques, newer culture-independent approaches including 16S rRNA gene sequencing have shown a more varied and dynamic vaginal microbial population.

- Studies on vaginal bacteria have shown their relevance not only for local health but also for general reproductive results, which guides treatments including probiotic treatments to restore and preserve microbial balance.

Normal Microbiota of Gastrointestinal Tract

- Each of the several anatomical sections—esophagus, stomach, jejunum/upper ileum, distal small intestine, and large intestine—which make up the gastrointestinal tract has a different microbial population affected by local physiological circumstances.

- Though thorough research is lacking, temporary colonisation by oropharyngeal bacteria and Yeasts occurs in the oesophagus most likely via food and secretions passing from nearby areas.

- Low pH from hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes like pepsinogen defines the hostile environment of the stomach, which produces a sparse microbial population dominated by acid-tolerant organisms like Lactobacillus species, Streptococcus species, and, in some individuals, Helicobacter pylori, which is linked to gastritis and ulcer formation.

- With a mostly anaerobic flora including Lactobacillus, Peptostreptococcus, Streptococcus, Porphyromonas, and Prevotella, the microbial count in the jejunum and upper ileum is low (fewer than 10^5 organisms per mL); this community can change to resemble colonic flora in conditions of stasis or obstruction, leading to malabsorption.

- Comprising mostly anaerobes that set the scene for the dense microbial community of the large intestine, the distal small intestine acts as a transitional zone with a greater and more varied microbial population (around 10^8–10^9 organisms per gramme of faeces).

- The large intestine is the most densely populated segment, hosting over 10^8 aerobic bacteria and up to 10^11 anaerobic bacteria per gramme of faeces; it features a complex ecosystem with key bacterial groups including Bifidobacterium species, Bacteroides (notably Bacteroides fragilis and the more numerous Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron), various Eubacterium species (such as E. aerofaciens, E. cylindroides, E. lentum, and E. rectale), Enterococcus species (primarily E. faecalis and E. faecium), and facultative anaerobes like Escherichia coli.

- While additional genera like Streptococcus and Actinomyces are also recovered from faecal specimens, other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family—such as Citrobacter, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Proteus species—can establish residence in the large intestine.

- Along with lesser concentrations of Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, and Prevotella species, the large intestine also hosts spore-forming Bacillus and Clostridium species; numerous yeasts (e.g., Candida species) and protozoa help to contribute to the general microbial complexity.

- Variations in pH levels, oxygen availability, food content, and mucosal defences produce the different microbial communities seen throughout the gastrointestinal tract—all of which are vital for preserving human digestive and immunological systems.

Normal Microbiota of Genitourinary Tract

- The urinary and reproductive systems combined make up the genitourinary tract, and each hosts unique microbial population that supports local immunity and health.

- Usually dominated by Lactobacillus species, which generate lactic acid to preserve a low pH environment that limits the growth of possible pathogens, other bacteria may also be present in lesser quantities in women.

- Now known to have a resident microbiota—identified by culture-independent techniques—the female urinary system, including the bladder, contains common taxa like Lactobacillus, Corynebacterium, and sometimes Staphylococcus, which could help to avoid urinary tract infections.

- The urethral microbiota in men is usually sparse and reflects the skin flora; most organisms are Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, and several Streptococcus species; although the upper urinary tract is usually thought to be sterile, new data suggest low-level colonisation may occur.

- The makeup and diversity of the genitourinary microbiota can be influenced by age, hormonal state, sexual activity, and antibiotic usage, therefore influencing susceptibility to infections and general urogenital health.

- Advances in sequencing technology and molecular diagnostics have exposed a more complex and dynamic microbial ecology in the genitourinary tract than formerly known, therefore stressing its relevance in preserving mucosal immunity and avoiding colonisation by infections.

Normal Microbiota of the Conjunctiva

- In healthy people the conjunctiva, a mucous membrane covering the front surface of the sclera and the inside surface of the eyelids, usually supports few, if any, bacteria.

- Though their presence is usually ephemeral and in low quantities, the bacterial genera most usually found on the conjunctiva when detected are Staphylococcus and Haemophilus.

- The tear film’s antibacterial proteins— lysozyme, lactoferrin, and secretory immunoglobulin A—which stop microbial growth—help to sustain the conjunctival naturally low microbial burden.

- The natural defences of the ocular surface and consistent mechanical washing (by blinking) help to restrict microbial colonisation even more, therefore producing a less varied microbiome than other mucosal locations.

- Disturbances in this delicate equilibrium, including those brought on by ocular illnesses or immunosuppression, might cause changes in the conjunctival microbiota, so raising or lowering of susceptibility to infections.

Factors Determining the Normal Flora of Human Body

- Anatomical Site: Normal flora’s composition differs greatly depending on the anatomical location because of changes in ambient circumstances like temperature, moisture, pH, and nutrition availability. For example, although the wet, nutrient-rich environment of the large intestine supports a varied microbial population dominated by anaerobic bacteria, the skin’s dry and acidic environment favours the growth of gram-positive bacteria like Staphylococcus epidermidis. ”

- Age: A person’s typical flora varies in composition and variety during their lifetime. From their moms and the surroundings, newborns pick up first microbial communities that eventually stabilise. Changes in nutrition, immune system, and physiology can affect the microbiome composition in older people.

- Diet: The gut bacteria is strongly influenced by eating patterns. Whereas plant-based diets encourage the growth of fiber-digesting bacteria like Roseburia and Eubacterium rectale, diets heavy in animal proteins and lipids often enhance the presence of bile-tolerant microorganisms like Bacteroides.

- Hormonal Factors: Particularly in the female reproductive system, hormonal changes might influence the natural flora. For instance, higher oestrogen levels throughout puberty cause glycogen to be deposited in vaginal epithelial cells, therefore fostering the development of lactobacilli and hence preserving an acidic vaginal pH.

- Personal Hygiene: Personal hygiene can change the makeup of typical flora. Overuse of antimicrobial products might lower microbial diversity, therefore upsetting the balance between harmful and commensal microbes.

- Antibiotic Usage: Antibiotics can upset the usual flora by killing sensitive bacteria, therefore causing proliferation of either resistant species or opportunistic diseases. Conditions like antibiotic-associated diarrhoea might follow from this disturbance.

- Immune System Status: A damaged immune system brought on by sickness or immunosuppressive treatments might change the usual flora, therefore raising the vulnerability to opportunistic pathogens.

- Environmental Exposure: Variations in microbial exposure can affect the variety and composition of normal flora by means of contact with diverse habitats, including rural against urban ones. ”

- Genetic Factors: By influencing immune responses and the synthesis of antimicrobial peptides, host genetics can impact the makeup of normal flora and thus shape the microbial populations colonising the body.

- Health Status: Chronic disorders as diabetes and obesity can change the usual flora, therefore aggravating disease progression and compromising general health.

Role of normal flora in Human Body

Beneficial Effects of Normal Flora

- By means of food competition and synthesis of inhibitory compounds, normal flora competently occupy ecological niches on the skin, in the stomach, and other mucosal surfaces, therefore preventing the adherence and growth of pathogenic organisms.

- By inducing the development and control of both innate and adaptive immune responses, including the maturation of gut-associated lymphoid tissue and the enhancement of immunoglobulin, commensal microbes assist regulate the immune system of the host. An output

- Many helpful bacteria break down indigestible food fibers to generate short-chain fatty acids such butyrate, acetate, and propionate, which colon cells need for energy and help to generate anti-inflammatory signals in the gastrointestinal tract.

- Normal flora augment the nutritional needs of the host by synthesizing vital vitamins—such as vitamin K and numerous B vitamins—that are vital for activities including blood coagulation and cellular metabolism.

- Through their stimulation of mucins and tight junction proteins, which preserve intestinal permeability and guard against systemic inflammation, commensal bacteria promote the integrity of mucosal barriers.

- Maintaining equilibrium, the typical microbiota’s metabolic activity includes biotransformation of bile acids and xenobiotics, therefore facilitating effective lipid digestion and detoxification activities.

- By generating antimicrobial agents like organic acids and bacteriocins, the normal flora directly protects against colonization and spread of dangerous bacteria.

Harmful Effects of Normal Flora

- As evidenced by skin bacteria like Staphylococcus epidermidis causing infections in individuals with indwelling medical devices, normal flora can become opportunistic pathogens when the host’s immune systems are impaired or when natural barriers are broken.

- Often following surgery or trauma, translocation of commensal organisms from their regular locations into sterile regions can cause bacteremia and sepsis, therefore showing the potential for these generally benign bacteria to cause systemic illnesses.

- Using antibiotics disturbs the gut microbial balance, leading to dysbiosis and overgrowth of pathogenic species like Clostridium difficile, which causes severe antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis.

- Normally contributing to oral health, oral commensals can become dangerous if they reach the circulation during dental operations, therefore raising the risk of diseases like infective endocarditis in sensitive individuals.

- Normal flora might have antibiotic resistance genes, which would act as reservoirs for multidrug-resistant organisms to arise and spread, thereby complicating clinical treatment choices.

Significance of Normal Flora

- By actively occupying ecological niches, normal flora provide a first line of protection against pathogenic bacteria, therefore limiting chances for the establishment of destructive species.

- They are essential for the generation and control of both natural and adaptive immunological responses, including activation of mucosal immunity and the synthesis of immunoglobulin A, therefore preserving immune homeostasis.

- By digesting indigestible food components into short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, acetate, and propionate and by synthesis of vital vitamins like vitamin K and B vitamins, commensal microbes help host nutrition.

- By encouraging mucin generation and improving tight junction formation—two processes essential for stopping the transfer of pathogens into sterile body sites—they assist preserve the structural integrity of epithelial barriers.

- Effective digestion and detoxification depend on the metabolic activities of normal flora, which also include xenobiotic metabolism and bile acid conversion, therefore affecting the general host metabolic balance.

- Normal flora assist avoid too strong inflammation and lower the risk of autoimmune and allergy diseases by adjusting inflammatory responses through the synthesis of regulating metabolites.

- Normal flora’s long-term co-evolution with their human host has produced a mutually beneficial connection supporting health; disturbances in this equilibrium (dysbiosis) might predispose people to certain illnesses.

- Developing focused treatments like probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation, which try to restore or improve the beneficial activities of these microbial populations, depends on an awareness of the relevance of normal flora.

- Bailey & Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology. Editors: Bettey A. Forbes, Daniel F. Sahm & Alice S. Weissfeld, 12th ed 2007, Publisher Elsevier.

- Clinical Microbiology Procedure Handbook Vol. I & II, Chief in editor H.D. Isenberg, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, Publisher ASM (American Society for Microbiology), Washington DC.

- Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Editors: Connie R. Mahon, Donald G. Lehman & George Manuselis, 3rd edition2007, Publisher Elsevier.

- Normal Flora of the Human Body. (2021, April 24). https://bio.libretexts.org/@go/page/51151

- Normal Microbiota of the Body. (2021, March 6). https://bio.libretexts.org/@go/page/31846

- https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/pathophysiology/chapter/innate-non-specific-defenses-of-the-human-body-to-pathogens-normal-flora-phagocytes-complement-proteins-interferons-inflammation-and-fever/

- https://studyrocket.co.uk/revision/level-3-health-and-social-care-btec/microbiology-for-health-science/role-of-normal-flora-and-the-human-body

- https://www.onlinebiologynotes.com/normal-flora-human-host-types-examples-roles/

- https://onlinesciencenotes.com/normal-microbial-flora-and-their-roles-in-the-human-body/

- https://microbiologynotes.org/normal-microbiota-of-the-healthy-human-body/

- https://www.nios.ac.in/media/documents/dmlt/Microbiology/Lesson-07.pdf

- https://biologyreader.com/normal-flora-of-human-body.html

- https://universe84a.com/normal-flora/

- https://medicallabnotes.com/normal-flora-introduction-types-distribution-on-human-body-beneficial-role-harmful-effects-and-keynotes/

- Text Highlighting: Select any text in the post content to highlight it

- Text Annotation: Select text and add comments with annotations

- Comment Management: Edit or delete your own comments

- Highlight Management: Remove your own highlights

How to use: Simply select any text in the post content above, and you'll see annotation options. Login here or create an account to get started.