What is Fasciolopsis Buski?

- Fasciolopsis buski, commonly referred to as the giant intestinal fluke, is a species of parasitic flatworms belonging to the genus Fasciolopsis. It is the only species in this genus that is recognized to affect humans and pigs, with significant medical and veterinary relevance. This parasite is prevalent in Southern and Eastern Asia, where it primarily affects populations living in areas with poor sanitation and close proximity to contaminated water sources.

- The lifecycle of Fasciolopsis buski involves several stages. The adult fluke lives in the intestines of humans and pigs, where it releases eggs into the host’s feces. When these eggs come into contact with freshwater, they hatch into larvae (miracidia), which infect snails, the intermediate host. Inside the snail, the larvae undergo further development into cercariae, which are released back into the water. These cercariae encyst on aquatic plants, forming metacercariae. Humans and pigs become infected when they consume these contaminated plants, such as water chestnuts or lotus.

- Once inside the host, the metacercariae excyst in the intestines and mature into adult flukes. These adult worms can grow to several centimeters in length, making them one of the largest intestinal flukes affecting humans. The presence of adult flukes in the intestines can lead to various symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and malnutrition. In severe cases, the infection can cause intestinal obstruction or other gastrointestinal complications.

- The disease caused by Fasciolopsis buski is known as fasciolopsiasis. It is primarily associated with areas where sanitation is poor, and aquatic plants are a common part of the diet. Prevention involves proper sanitation practices, such as treating contaminated water, cooking aquatic plants thoroughly before consumption, and limiting human exposure to infested water sources.

History and Distribution of Fasciolopsis Buski

Its discovery dates back to the mid-19th century and its distribution spans several regions in Asia, where it continues to be a health concern.

- First discovery (1843): Fasciolopsis buski was first described by a British surgeon named George Busk in 1843. He found the parasite in the duodenum of an East Indian sailor who had died in London. This marked the beginning of scientific knowledge about this trematode.

- Common regions of prevalence:

- The parasite is widespread in Southern and Eastern Asia, especially in regions where sanitation conditions are poor, and water plants are consumed without proper cooking.

- It is a common parasitic infection in humans and pigs in China and several Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos.

- Distribution in India:

- In India, cases of Fasciolopsis buski infections have been recorded primarily in the northeastern states, particularly Assam and West Bengal.

- These regions are characterized by the use of aquatic plants as a staple in the diet, which increases the risk of infection through contaminated plants.

- Habitat and environmental factors:

- The parasite thrives in areas where water bodies, such as ponds and rice fields, are commonly used for growing aquatic plants like water chestnuts and lotus.

- The snail, which serves as the intermediate host, is abundant in these water bodies, facilitating the lifecycle of the parasite.

- Impact on humans and animals:

- The fluke infects the intestines of humans and pigs, causing fasciolopsiasis. This condition is often linked to the ingestion of raw or improperly cooked aquatic plants, allowing the parasite to complete its life cycle.

- Although pigs are the primary reservoir hosts, humans become accidental hosts when they consume these contaminated plants.

- Global significance:

- Despite its primary distribution in Asia, the study and control of Fasciolopsis buski remain important in global parasitology due to the health risks it poses in endemic regions.

- Preventive strategies, including improving sanitation and educating communities about proper food preparation, are essential to reduce its transmission.

Habitat of Fasciolopsis Buski

Its habitat is closely tied to regions where aquatic plants, freshwater, and specific snail species coexist, making certain areas in Asia particularly conducive to its survival and transmission. This parasitic trematode thrives in environments where water plays a central role in agriculture and daily living.

- Freshwater bodies:

- Fasciolopsis buski is commonly found in freshwater environments like ponds, rivers, and rice paddies. These water bodies provide the necessary conditions for the intermediate host, snails, to thrive and for the parasite’s lifecycle to progress.

- Intermediate host (snail habitat):

- Snails of the genus Segmentina serve as the intermediate host for Fasciolopsis buski. These snails live in slow-moving or stagnant freshwater, where they become infected with the parasite’s larvae, known as miracidia. Inside the snail, the miracidia develop into cercariae, which are later released into the water.

- Aquatic plants:

- The adult fluke’s eggs are released into the environment through the feces of infected hosts, and after hatching and developing in snails, the larvae (cercariae) attach to aquatic plants. Common plants that serve as transmission vehicles for the parasite include water chestnuts, lotus, and other edible water plants, which are often consumed raw or undercooked by humans and pigs.

- Regional distribution:

- The habitat of Fasciolopsis buski is concentrated in regions of Southern and Eastern Asia, including countries like China, Thailand, Vietnam, and India. In these areas, the combination of freshwater ecosystems, snail populations, and the cultivation of aquatic plants creates an ideal environment for the parasite’s lifecycle.

- Human and animal habitat intersection:

- Humans and pigs, the primary hosts of Fasciolopsis buski, become infected by ingesting metacercariae that have encysted on aquatic plants. This typically occurs in rural or agricultural settings where water plants are a common dietary staple, and water sources are not well managed for sanitation. The close proximity between humans, pigs, and contaminated freshwater systems increases the risk of infection.

- Geographical hotspots in India:

- In India, Fasciolopsis buski is predominantly found in Assam and West Bengal. These regions have numerous water bodies that support aquatic vegetation, and the reliance on such plants as a food source heightens the likelihood of parasite transmission.

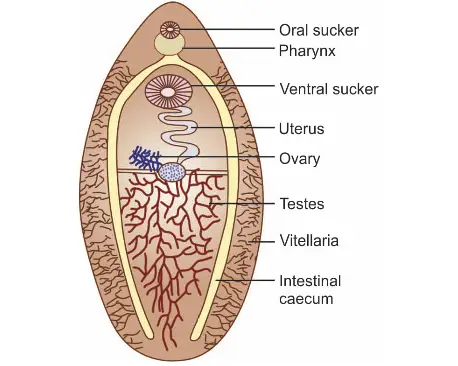

Morphology of Fasciolopsis Buski

Fasciolopsis buski, commonly known as the giant intestinal fluke, is the largest trematode to infect humans. Its morphology is well-suited to its parasitic lifestyle, and a detailed examination of both the adult worm and its eggs reveals key characteristics important for its identification and function.

- Adult worm characteristics:

- The adult Fasciolopsis buski is large and fleshy, measuring between 20–75 mm in length and 8–20 mm in width, with a thickness of about 0.5–3 mm.

- It is the largest trematode that infects humans, while the smallest is Heterophyes.

- The worm has an elongated, ovoid shape and is equipped with two suckers for attachment: a small oral sucker located at the anterior end and a larger acetabulum, or ventral sucker, used to anchor itself to the host’s intestinal wall.

- Unlike Fasciola hepatica, Fasciolopsis buski lacks a cephalic cone, giving it a more streamlined appearance.

- The digestive system consists of two unbranched intestinal caeca, a distinguishing feature compared to other trematodes where the intestinal branches may be present.

- The lifespan of the adult worm inside the human or pig host is approximately six months, during which it can cause significant health issues if not treated.

- Egg characteristics:

- Fasciolopsis buski produces operculated eggs, which are similar in structure to those of Fasciola hepatica. An operculum refers to the lid-like structure on the egg that allows the larva to emerge when it hatches.

- These eggs are laid in the lumen of the host’s intestine and are expelled with feces. The adult worm produces an enormous number of eggs, laying about 25,000 eggs per day.

- The high number of eggs contributes to the rapid spread of the parasite, especially in regions where water contamination and poor sanitation are prevalent.

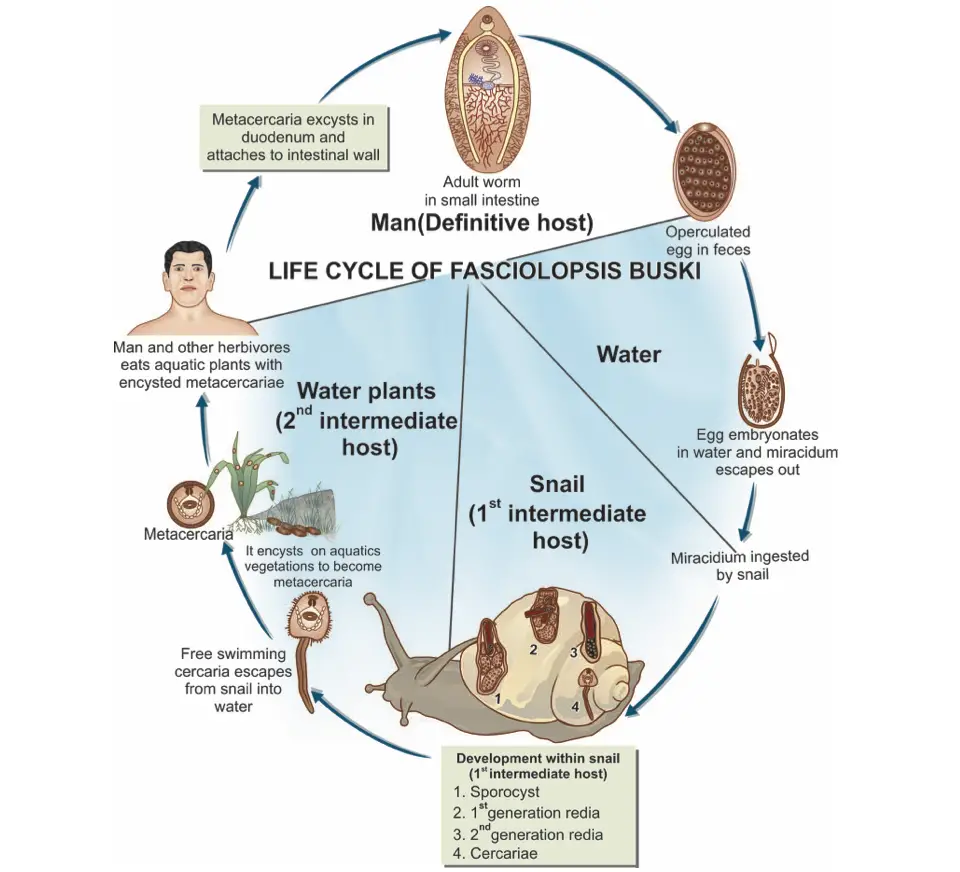

Life Cycle of Fasciolopsis Buski

Fasciolopsis buski is a parasitic flatworm that primarily affects humans and pigs, leading to fasciolopsiasis, a disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Understanding the life cycle of this trematode is crucial for controlling its transmission and preventing infection. The cycle is complex and involves a definitive host, two intermediate hosts, and several developmental stages. The following points elucidate the life cycle of Fasciolopsis buski:

- Hosts:

- Definitive Hosts: Humans and pigs are the primary definitive hosts, with pigs often acting as a reservoir for the infection.

- First Intermediate Host: Snails belonging to the genus Segmentina serve as the first intermediate host, playing a pivotal role in the development of the parasite.

- Second Intermediate Host: Aquatic plants, including the roots of the lotus and the bulbs of water chestnuts, act as the second intermediate hosts. The encystment of the parasite occurs on these plants.

- Infective Form:

- The infective form is represented by encysted metacercariae, which are found on aquatic vegetation. These metacercariae are responsible for transmitting the infection when consumed.

- Egg Development:

- The life cycle begins when eggs are excreted in the feces of the definitive host. In water, these eggs hatch within approximately six weeks, releasing larvae known as miracidia.

- Miracidia are motile and swim in search of a suitable host.

- Penetration of Intermediate Host:

- Upon contacting a snail of the genus Segmentina, miracidia penetrate the snail’s tissues. Within the snail, the parasite undergoes a series of transformations:

- Sporocyst Stage: The miracidia develop into sporocysts.

- Rediae Generation: The sporocysts give rise to the first and second generation of rediae, which further develop within the snail.

- Cercariae Formation: Eventually, the cercariae are produced, which are free-swimming larvae.

- Upon contacting a snail of the genus Segmentina, miracidia penetrate the snail’s tissues. Within the snail, the parasite undergoes a series of transformations:

- Encystment on Aquatic Vegetation:

- After escaping from the snail, the cercariae encyst on the roots of lotus plants, bulbs of water chestnuts, and other aquatic vegetation, forming metacercariae.

- Transmission to Definitive Host:

- When humans or pigs consume the contaminated aquatic plants, the encysted metacercariae are ingested.

- Upon reaching the duodenum of the host, the metacercariae excyst, shedding their protective encystment.

- Development into Adult Form:

- Once excysted, the metacercariae attach to the mucosa of the intestines and begin their maturation process. This transformation into adult flukes occurs over approximately three months.

- Reproduction:

- Adult Fasciolopsis buski are capable of producing thousands of eggs daily, which continue the cycle when excreted by the definitive host.

Pathogenesis of Fasciolopsis Buski

The following points detail the pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical manifestations associated with fasciolopsiasis:

- Infection Mechanism:

- The primary mode of infection occurs when encysted metacercariae are ingested through contaminated aquatic plants. Once consumed, these metacercariae excyst in the duodenum and adhere to the intestinal mucosa.

- Tissue Attachment and Damage:

- The larvae attach to the duodenal and jejunal mucosa, leading to:

- Traumatic Injury: The mechanical attachment and movement of the larvae can disrupt the epithelial integrity.

- Inflammatory Response: This injury incites an inflammatory reaction, resulting in localized inflammation and ulceration of the intestinal lining.

- The larvae attach to the duodenal and jejunal mucosa, leading to:

- Local and Systemic Effects:

- As the adult worms develop, they can exert several detrimental effects, including:

- Clinical Manifestations:

- The initial symptoms of fasciolopsiasis often include:

- Diarrhea: Frequent loose stools can result from impaired absorption and intestinal irritation.

- Abdominal Pain: Discomfort or pain in the abdomen arises from inflammation and ulceration.

- The initial symptoms of fasciolopsiasis often include:

- Toxicity and Allergic Reactions:

- Besides mechanical damage, the worms release toxic metabolites, leading to:

- Intoxication: The release of toxic substances contributes to the overall clinical picture, causing systemic effects.

- Sensitization: The immune response to the toxins can result in allergic symptoms, including:

- Edema: Swelling due to fluid retention and inflammation.

- Ascites: Accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity, which can occur in severe cases.

- Anemia: Caused by chronic inflammation and nutritional deficiencies.

- Besides mechanical damage, the worms release toxic metabolites, leading to:

- Severe Complications:

- In cases of heavy infection, the complications can escalate, manifesting as:

- Bowel Obstruction: Adult worms may cause partial obstruction of the intestinal lumen.

- Paralytic Ileus: Though rare, this condition occurs when there is a cessation of intestinal activity, resulting in bowel paralysis.

- In cases of heavy infection, the complications can escalate, manifesting as:

- Chronic Symptoms:

- Persistent diarrhea and overall debilitation can lead to significant morbidity, affecting the quality of life and nutritional status of the infected individuals.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Fasciolopsis Buski

- Clinical History:

- The diagnostic process often begins with obtaining a thorough clinical history.

- A history of residence in endemic areas where Fasciolopsis buski is prevalent significantly raises suspicion of the infection.

- Symptomatology:

- Awareness of clinical symptoms, such as abdominal pain and diarrhea, supports the need for further diagnostic evaluation.

- Symptomatic patients may exhibit signs of malabsorption or nutritional deficiencies, which can indicate parasitic infection.

- Stool Examination:

- The primary method for confirming fasciolopsiasis is through the examination of fecal samples.

- The presence of Fasciolopsis buski eggs can be detected in stool specimens, typically requiring a concentration technique to enhance the visibility of the eggs.

- Egg Identification:

- The eggs of Fasciolopsis buski are large, operculated, and have a distinctive shape, facilitating identification under the microscope.

- Microscopic examination involves preparing stool smears and utilizing appropriate staining techniques to enhance visualization.

- Purgative or Antihelminthic Administration:

- In certain cases, administration of a purgative or antihelminthic drug may be performed to facilitate the expulsion of adult worms from the intestines.

- Following treatment, careful examination of stool samples can reveal the presence of adult Fasciolopsis buski, thus confirming the diagnosis.

- Serological Testing:

- Although less commonly used, serological tests can be employed to detect specific antibodies against Fasciolopsis buski.

- These tests can assist in cases where stool examination yields inconclusive results.

- Imaging Techniques:

- In cases of severe infection or complications, imaging techniques such as ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scans may be utilized.

- These imaging modalities can help visualize any potential obstruction or abnormal findings in the gastrointestinal tract.

- Differential Diagnosis:

- It is essential to consider and rule out other parasitic infections that may present with similar symptoms.

- A thorough diagnostic process helps differentiate fasciolopsiasis from conditions such as strongyloidiasis or other intestinal helminthic infections.

- Summary of Diagnostic Steps:

- Step 1: Obtain a clinical history focusing on residence in endemic areas and symptomatology.

- Step 2: Collect and examine stool samples for the presence of eggs.

- Step 3: If necessary, administer purgatives to recover adult worms for identification.

- Step 4: Consider serological tests and imaging if initial tests are inconclusive.

Treatment

- Primary Drug of Choice:

- Praziquantel: This is the primary medication used for the treatment of fasciolopsiasis. Praziquantel acts by:

- Disrupting the integrity of the parasite’s cell membrane.

- Inducing muscular paralysis in the adult flukes, facilitating their expulsion from the gastrointestinal tract.

- Praziquantel: This is the primary medication used for the treatment of fasciolopsiasis. Praziquantel acts by:

- Alternative Treatments:

- Besides praziquantel, other compounds have shown effectiveness in managing fasciolopsiasis:

- Hexylresorcinol: This antiseptic and anthelmintic agent has been found useful against Fasciolopsis buski.

- Tetrachlorethylene: This solvent is also considered a potential treatment option, although its use is less common compared to praziquantel.

- Besides praziquantel, other compounds have shown effectiveness in managing fasciolopsiasis:

- Administration Protocol:

- The treatment typically involves a single oral dose of praziquantel, which is well-tolerated by most patients.

- In some cases, the dosage may be adjusted based on the severity of the infection and the patient’s overall health.

- Symptomatic Management:

- Alongside specific antiparasitic treatment, symptomatic management is essential to address clinical manifestations such as:

- Abdominal Pain: Analgesics may be administered to relieve discomfort.

- Diarrhea: Antidiarrheal medications can be used to manage frequent loose stools.

- Nutritional Support: Providing nutritional supplementation may be necessary, especially in cases of malabsorption or significant weight loss.

- Alongside specific antiparasitic treatment, symptomatic management is essential to address clinical manifestations such as:

- Follow-Up and Monitoring:

- Post-treatment follow-up is vital to ensure the effectiveness of the therapy.

- Stool examinations may be conducted to confirm the absence of eggs, indicating successful treatment.

- Preventive Measures:

- To reduce the risk of reinfection and transmission, education on proper hygiene and sanitation is essential.

- Avoiding the consumption of contaminated aquatic plants can significantly decrease the incidence of fasciolopsiasis.

- Considerations for Special Populations:

- Special care may be required when treating pregnant or lactating individuals, as the safety profile of some medications may be different in these populations.

Prophylaxis

The following points highlight the key strategies for preventing fasciolopsiasis:

- Treatment of Infected Individuals:

- Prompt treatment of individuals diagnosed with fasciolopsiasis is critical to reducing the reservoir of infection.

- By treating infected persons, the shedding of eggs in feces is minimized, which in turn decreases the risk of transmission to others.

- Hygienic Practices:

- Ensuring proper hygiene is paramount in preventing the spread of fasciolopsiasis. This includes:

- Adequate washing of water vegetables, particularly those consumed raw.

- It is recommended to wash these vegetables in hot water to effectively eliminate potential encysted metacercariae.

- Ensuring proper hygiene is paramount in preventing the spread of fasciolopsiasis. This includes:

- Water Source Management:

- Preventing contamination of water bodies such as ponds and streams is crucial. This can be achieved by:

- Implementing measures to ensure that human and pig excreta do not contaminate these water sources, thus reducing the likelihood of infection.

- Preventing contamination of water bodies such as ponds and streams is crucial. This can be achieved by:

- Fertilizer Safety:

- The use of night soil as fertilizer poses a risk of transmission if not properly treated. Therefore:

- It is essential to sterilize night soil before application to eliminate any viable eggs or larvae that could infect humans or animals.

- The use of night soil as fertilizer poses a risk of transmission if not properly treated. Therefore:

- Snail Control:

- Since snails of the genus Segmentina serve as the first intermediate host for Fasciolopsis buski, controlling their populations is vital. Strategies may include:

- Implementing environmental management practices to reduce snail habitats.

- Utilizing molluscicides where appropriate to decrease snail populations in affected water bodies.

- Since snails of the genus Segmentina serve as the first intermediate host for Fasciolopsis buski, controlling their populations is vital. Strategies may include:

- Public Awareness Campaigns:

- Educating communities about the transmission routes of fasciolopsiasis and the importance of preventive measures can enhance compliance with hygiene practices.

- Awareness campaigns can inform the public about the risks associated with consuming untreated aquatic plants and the necessity of proper food handling.

- Surveillance and Monitoring:

- Establishing surveillance systems in endemic areas helps monitor the incidence of fasciolopsiasis and assess the effectiveness of prophylactic measures.

- Regular monitoring of water quality and snail populations can guide intervention strategies.

- Community Involvement:

- Engaging local communities in prevention efforts fosters a sense of ownership and responsibility for reducing the incidence of fasciolopsiasis.

- Community-led initiatives can promote sustainable agricultural practices and safe water management.

- https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/fasciolopsiasis/index.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/fasciolopsis/about/index.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fasciolopsis