What are Cereals?

Cereals are among the most vital sources of plant-based food for humans and animals. They have held this significance since ancient times, with their cultivation dating back so far that their wild ancestors are no longer recognizable. Over centuries, numerous species and varieties have been developed, even before recorded history. The ancient civilizations, such as the Romans and Greeks, were already familiar with several types of cereals like wheat and barley, which they attributed to divine powers in their religious practices.

The term “cereal” itself originates from Roman festivals held in honor of the goddess Ceres, the deity of grain and agriculture. These festivals featured offerings of wheat and barley, known as the “cerealia munera,” which influenced the modern word. Similarly, various ancient cultures, including those in the Americas, worshiped deities associated with agriculture and offered the first fruits of their harvests in religious ceremonies.

Botanically, cereals are members of the Gramineae family, also known as the grass family. They produce a specific type of fruit known as the karyopsis, where the seed wall fuses with the ripened ovary wall to create the grain husk. The term “grain” can refer either to this type of fruit or the plant that produces it. The six true cereals include barley, maize (corn), oats, rice, rye, and wheat. Among these, wheat, maize, and rice are the most significant, playing crucial roles in the development of civilizations.

While some plants like millet, sorghum, and buckwheat are sometimes mistakenly categorized as cereals, true cereals offer several distinct advantages. One of the primary reasons for their importance is their adaptability to different climates. Barley and rye thrive in colder northern regions, wheat in temperate zones, and maize and rice in tropical and warmer areas. They also vary in their soil and moisture requirements, making them versatile crops for diverse environments.

Cereals are easy to cultivate with minimal labor and produce high yields. Their grains have a low water content, making them easy to store and handle. Nutritionally, cereals are rich in carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, making them a high-value food source. Additionally, they contain essential vitamins, further enhancing their role in human and animal diets.

Wheat

- Wheat is a key cereal crop primarily cultivated in temperate regions. It holds significant importance, particularly among populations in these climates, due to its widespread cultivation and versatility as a food source. The exact origin of wheat remains debated, but some recent studies suggest that its origins may lie in the highlands of Palestine and Syria. Other theories propose the Central Asian plateau or the Tigris and Euphrates valleys as potential regions of origin.

- Nikolai Vavilov, a prominent plant geneticist, theorized that wheat may have had multiple points of origin. According to his research, soft wheat varieties likely originated from the mountainous regions of Afghanistan and the southwestern Himalayas. In contrast, durum wheat may have developed in regions such as Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia), Algeria, and Greece. An early species of wheat known as einkorn possibly came from Asia Minor.

- Historically, wheat has been a vital crop for many ancient civilizations. It played a central role in the Babylonian economy and was widely cultivated by the Greeks, Romans, and other early cultures. Prominent ancient scholars like Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Pliny the Elder wrote about various wheat varieties. In fact, wheat was grown in China as early as 2700 B.C., and archaeological evidence indicates its use by the Lake Dwellers of Switzerland and Hungary during the Stone Age.

- The introduction of wheat to the New World occurred in 1529 when Spanish settlers brought it to Mexico. Over time, wheat spread to other parts of the Americas. The English explorer Bartholomew Gosnold sowed wheat in New England in 1602, and by 1611, it had reached Virginia. In 1769, wheat cultivation extended to California, and by 1845, it was being grown in Minnesota.

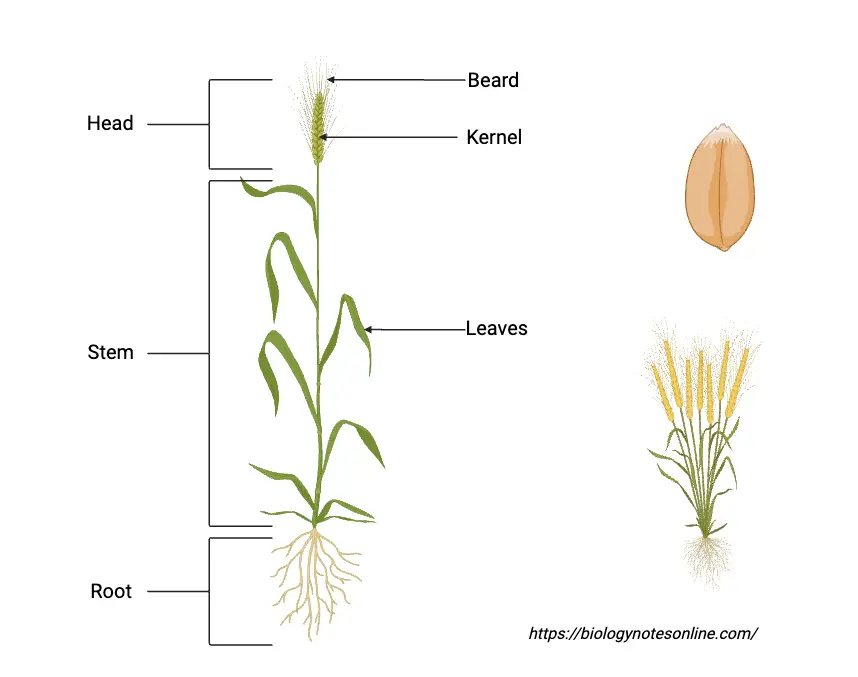

Morphology of Wheat

Wheat (Triticum spp.) is a cereal plant that has a distinct morphology, which can be divided into several key components:

- Roots:

- Primary Root: The first root to emerge from the germinating seed.

- Seminal Roots: These are the initial roots formed from the seed, anchoring the plant.

- Fibrous Root System: Comprises the adventitious roots that develop from the base of the stem, providing additional support and nutrient uptake.

- Stem:

- Culms: The main stem of the wheat plant, which is typically hollow and segmented into nodes and internodes.

- Nodes: The points on the stem where leaves and branches arise.

- Internodes: The segments between nodes, which elongate to increase the height of the plant.

- Leaves:

- Leaf Blade: The flat, broad part of the leaf responsible for photosynthesis.

- Leaf Sheath: The tubular part of the leaf that wraps around the stem.

- Ligule: A small, membranous structure at the junction of the leaf blade and sheath.

- Auricles: Small, ear-like projections at the base of the leaf blade that can help clasp the stem.

- Inflorescence:

- Spike: The inflorescence of wheat is a spike, which is an elongated flower cluster where the individual flowers are attached directly to the central axis.

- Spikelets: The individual units of the spike, each containing one or more flowers.

- Flowers:

- Florets: Each spikelet contains one to several florets, which are the individual flowers.

- Pistil: The female reproductive part of the flower, which includes the ovary, style, and stigma.

- Stamens: The male reproductive parts, consisting of anthers and filaments.

- Grains:

- Caryopsis: The type of fruit produced by wheat, where the seed coat is fused with the ovary wall. Each grain is a small, hard, and dry structure that contains the embryo and endosperm.

Characteristics of Wheat

- Botanical Classification:

- Wheat is classified as an annual grass under the genus Triticum, which includes a variety of both wild and cultivated species.

- While the wild forms of wheat are often considered weeds and have no significant value as food sources, the cultivated species, particularly Triticum aestivum, is widely grown for human consumption.

- Growth and Structure:

- Cultivated wheat typically grows between 2 to 4 feet in height.

- The plant produces an inflorescence, which is a terminal spike or head. This spike consists of 15 to 20 spikelets that are arranged along a zigzag axis.

- Each spikelet is sessile (attached without a stalk) and solitary, containing one to five individual flowers.

- Grain Composition:

- The mature wheat grain consists of several key components:

- Embryo: Represents about 6% of the grain and contains the genetic material necessary for germination.

- Starchy Endosperm: Makes up 82 to 86% of the grain, serving as the primary energy source through its high starch content.

- Aleurone Layer: A nitrogenous layer that accounts for 3 to 4% of the grain and is rich in proteins.

- Husk or Bran: Comprising 8 to 9% of the grain, this outer layer consists of the remains of the nucellus, the seed coat, and the ovary walls (also known as the pericarp).

- The mature wheat grain consists of several key components:

- Inflorescence Features:

- The wheat inflorescence is key to its reproduction and grain formation. The zigzag pattern of the spikelets enhances the plant’s ability to bear multiple flowers and subsequently more grains.

- Nutritional and Structural Importance:

- Each component of the wheat grain serves a specific function. The embryo facilitates reproduction, the starchy endosperm provides nutritional value, the aleurone layer adds essential proteins, and the husk protects the grain during development.

Types of Wheat

- Einkorn Wheat (Triticum monococcum):

- Also known as one-grained wheat, einkorn is one of the oldest wheat varieties, dating back to the Stone Age.

- It is a small plant, rarely exceeding 2 feet in height, and has a low yield.

- Einkorn is adapted to poor soils and is still grown in some mountainous regions of Southern Europe, especially in Spain. It is primarily used as fodder rather than for bread production.

- Emmer Wheat (Triticum dicoccum):

- Known as starch wheat or two-grained spelt, emmer has a flattened head with bristles or awns.

- Emmer is an ancient variety that was cultivated by early civilizations such as the Babylonians and Mediterranean nations.

- It is drought-resistant and thrives in dry soil, making it suitable for regions like Russia, Spain, and Italy. In the U.S., it is grown for livestock feed and breakfast cereals.

- Spelt Wheat (Triticum spelta):

- Spelt is a hardy, ancient wheat that grows well on poor soils.

- It has been cultivated for centuries in the Mediterranean region and is still grown in Spain.

- In the United States, spelt is mainly used for livestock feed.

- Polish Wheat (Triticum polonicum):

- This species, sometimes referred to as giant rye, is distinctive due to the long papery bracts around each spikelet.

- Although it has solid stems and flattened bluish-green ears, its yield is small and of limited value.

- Despite its name, Polish wheat is not native to Poland. It is primarily grown in Spain, Italy, and parts of Turkestan and Abyssinia.

- Poulard Wheat (Triticum turgidum):

- Also called English or river wheat, poulard wheat likely originated in the dry regions of the eastern and southern Mediterranean.

- It produces large heads but has a low yield, rendering it of little commercial significance.

- This wheat has been grown in the United States, but it has limited value.

- Club Wheat (Triticum compactum):

- Club wheat, also known as dwarf or hedgehog wheat, has short, compact heads and small kernels.

- It is well-suited for poor soils and is grown in mountainous regions of Central Europe, Turkestan, and Abyssinia.

- This wheat variety is soft and has a low protein content, making it unsuitable for bread-making but useful for pastry flour and export purposes.

- Durum Wheat (Triticum durum):

- Durum wheat is characterized by thick heads with long, stiff beards and hard, gluten-rich grains.

- It thrives in arid regions and has been cultivated in places like Spain, Algeria, India, and Russia.

- In the United States, durum wheat has proven to be highly valuable in the Great Plains due to its drought resistance. It is primarily used for making pasta, semolina, and macaroni, and when mixed with other flours, it can be used for bread.

- Common Wheat (Triticum aestivum):

- Common wheat is the primary source of bread flour and exists in numerous varieties that differ in morphology and physiology.

- It includes both hard and soft wheat varieties, with hard wheat being richer in proteins and soft wheat containing more starch.

- Common wheat is categorized into spring and winter varieties. Spring wheat is planted in spring and harvested in late summer, while winter wheat is sown in fall and harvested in early summer. Winter wheat generally yields more and is more disease-resistant than spring wheat.

Grades of Wheat

- Hard Red Spring Wheat (Class I):

- This class includes 24 varieties known by 80 different names, making up around 20% of the U.S. wheat crop.

- It is primarily grown in regions like Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Canada, where harsh winters prevent the cultivation of winter wheat.

- Marquis wheat is the most prominent variety, and this class is predominantly used for bread flour production due to its high gluten content.

- Durum Wheat (Class II):

- All varieties in this class are spring wheats, with the most notable being Kubanka. Durum wheat constitutes approximately 6% of the total wheat crop.

- It is mostly cultivated in the northern Great Plains and is known for its hardness, making it ideal for macaroni and pasta products.

- Hard Red Winter Wheat (Class III):

- Comprising 20 varieties known by 49 different names, hard red winter wheat accounts for about 40% of the total wheat crop.

- It is grown predominantly in the central and southern Great Plains, including Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma, where it thrives under hot summers and dry winters.

- The most prominent varieties include Turkey, Kharkov, and Kanred, and the flour produced from this wheat is highly valued for bread-making.

- Soft Red Winter Wheat (Class IV):

- Soft red winter wheat represents about 30% of the total wheat crop, with 66 distinct varieties and 400 different names.

- It is mainly cultivated in the eastern U.S., particularly east of the Mississippi River, and in the Pacific Northwest, where a more humid climate prevails.

- Due to its starchy grains, the flour is best suited for pastries, cakes, and home baking. This class also includes red club wheats.

- White Wheat (Class V):

- Making up roughly 5% of the U.S. wheat crop, this class encompasses all white-grained varieties, whether they are common or club wheats.

- White wheat varieties are grown in the Pacific Northwest and New York State and include both hard and soft as well as spring and winter wheats.

- The flour is commonly used for pastries and breakfast foods and is often blended with hard wheat flour for bread-making. This class also supports a significant export trade.

Cultivation of Wheat

- Climate Requirements:

- Wheat thrives in moderately dry temperate climates, avoiding warm, humid regions. A growing season of at least 90 days with a minimum annual rainfall of 9 inches is necessary. Excessive rainfall, exceeding 30 inches, can be detrimental.

- Ideal conditions include a cool, moist spring transitioning to a warm, dry harvest period. Different wheat varieties have specific climatic preferences.

- Global Cultivation Areas:

- The primary wheat-producing regions include southern Russia and the Danube plains, Mediterranean countries, Northwestern Europe, central plains of the United States and Canada, the Columbia River basin in the Pacific Northwest, northwest India, Argentina, and Southwest Australia.

- Soil Conditions:

- Wheat prefers clay and loam soils but can also grow in light sandy soils. However, overly wet conditions can reduce plant vigor and yield, while excessively porous soils may lack sufficient moisture retention.

- Soil fertility is enhanced with lime if calcium is deficient, and essential nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium should be added. Barnyard manure is an effective fertilizer.

- Land Preparation and Planting:

- Land must be thoroughly cleared to prevent weed competition. Crop rotation is practiced to control weeds, with wheat often planted after crops like beets, turnips, or tobacco.

- Planting timing depends on whether the wheat is a winter or spring annual. High-quality, fully ripe seeds are selected for planting. Seeds are cleaned by winnowing, sifting, and chemical treatment to remove dust, light grains, and fungus spores.

- Sowing Methods:

- Wheat can be sown broadcast by hand on small farms or using machines on larger farms. Machines either broadcast seeds or drill furrows to bury seeds.

- Germination occurs quickly, with first leaves appearing within two weeks. Spring wheat grows continuously until maturity, while winter wheat’s growth pauses during frost. Severe cold or root exposure can damage or kill winter wheat.

- Crop Maintenance:

- Regular weeding is necessary to prevent competition from weeds. Large farms use machines that can plow multiple furrows simultaneously.

- Wheat ripens through stages: milk-ripe, yellow-ripe or dough, full-ripe, and dead-ripe. Sometimes, wheat is harvested before full maturity to be used as fodder.

- Pests and Disease Management:

- Wheat is susceptible to insect and fungal pests, including bunt, smut, and rust. Rust, in particular, can cause significant crop losses.

- Efforts are ongoing to develop rust-resistant and drought-resistant wheat varieties, reflecting ongoing advancements in plant breeding. This work has gained attention through publications such as “Hunger Fighters” and “Red Rust.”

Harvesting of Wheat

- Harvesting Methods:

- The method of harvesting wheat depends largely on the size of the farm. Small-scale operations may use traditional tools, such as reaping hooks and scythes, to cut the wheat stalks. On larger farms, mechanized equipment, such as reaping machines, is employed.

- After cutting, binding machines gather and bind the wheat into sheaves. These sheaves are then stored in shelters to keep them dry and protected from the elements.

- Gleaning:

- In various regions, there is a tradition of allowing local residents to glean the remaining ears of wheat left in the fields after the main harvest. This practice provides additional food resources to those in need.

- Threshing:

- Threshing involves separating the grain from the spike. This process can be carried out manually using a flail, a method that, although labor-intensive, causes minimal damage to the grain.

- The wheat is laid out in rows on a threshing floor, and the flail is used to strike the stalks, followed by turning the wheat and repeating the process. In Europe, a cart that traces a spiral course over the stalks is commonly used to aid in threshing.

- Mechanized Threshing:

- Threshing machines, both horizontal and vertical, are often employed to expedite the process. These machines feature rapidly rotating drums with barbed beaters that strike the wheat ears at high speeds, sometimes up to 800 revolutions per minute.

- Combine Harvesters:

- In modern large-scale farming, combines represent the pinnacle of harvesting technology. These machines integrate multiple functions: reaping, cleaning, threshing, winnowing, and sifting the grains.

- Combines also separate wheat from chaff, eliminate foreign seeds, sort the grain into grades, and bag it. They can cover wide swaths of land, up to 40 feet in width, and with a crew of eight, can harvest approximately 120 acres per day.

- Storage:

- Proper storage is crucial to prevent spoilage and pest infestations. Wheat should be kept in well-constructed buildings that are resistant to pests and provide adequate ventilation. Structures with concrete walls and floors are preferred, though iron is also commonly used.

- In tropical regions, subterranean silos are often utilized. Additionally, large grain elevators at major ports facilitate the storage and distribution of wheat, with over 40,000 such facilities in the United States alone.

Milling of Wheat

- Historical Milling Methods:

- In ancient times, wheat grains were initially ground using simple methods, such as “braying” between two stones. This was followed by the use of a mortar and pestle and later by millstones powered by wind or water. These early mills featured a fixed lower stone and a movable upper stone, with grains introduced into the upper stone’s openings. The grinding surfaces of these stones were often cut with radiating lines to facilitate the grinding process.

- Modern Roller Milling Process:

- Cleaning and Scouring:

- The milling process begins with the cleaning and scouring of wheat grains. This involves screening to remove foreign seeds, dust, sticks, straw, and loose bran that could contaminate the flour. The grains are thoroughly washed and scoured to ensure they are clean before milling.

- Tempering:

- Following cleaning, the wheat undergoes tempering, which prepares it for milling. A small amount of water is added to toughen the bran and prevent it from breaking into smaller particles. This process ensures that the bran flakes out in larger pieces during milling.

- Breaking, Grinding, and Rolling:

- The conditioned wheat is subjected to a series of mechanical processes:

- First Break: The grains are ground between corrugated iron rollers, known as the “first break.” This initial grinding cracks and partially flattens the grains. A small amount of flour, termed “break flour,” is separated out using sieves, while the remaining material moves to the next stage.

- Second Break and Subsequent Stages: The partially flattened grain undergoes further processing through additional sets of rollers. Each set operates at a different speed and further separates the bran and embryo from the wheat. This process is repeated through five sets of rollers, with each stage involving bolting to separate the ground material from coarse bran.

- The conditioned wheat is subjected to a series of mechanical processes:

- Final Granulation and Bolting:

- After all bran has been removed, the purified wheat material is passed through smooth rollers for final granulation. The flour is then bolted through silk cloth with approximately 12,000 meshes per square inch. This final bolting results in high-quality flour, often referred to as the “First Patent.”

- Cleaning and Scouring:

- By-products and Variants:

- Middlings: The material separated out during milling, known as middlings, can be processed into lower-grade flours or used for other purposes.

- Semolinas: Granular particles that are intermediate in size between grain and flour are termed semolinas. Durum wheat semolina is used in macaroni production, while regular wheat semolina is used for farinas.

- Flour Variants:

- White Flour: The primary product of the milling process is white flour, which results from the complete removal of bran and other coarse particles.

- Graham Flour: This flour uses the entire grain, including the bran, resulting in a coarser texture.

- Whole-Wheat Flour: This type retains a portion of the bran, offering a balance between white flour and graham flour.

Wheat Products

- Bread and Bakery Products:

- Bread Flour:

- Wheat is a primary ingredient in bread production, with bread typically made from wheat flour. Hard wheats are particularly suited for this purpose, as their high gluten content provides the structure necessary for bread. Bread made from other cereals, such as corn or rye, is specified as such, e.g., corn bread or rye bread.

- Soft Wheat Flour:

- Flour derived from soft wheats is utilized in baking products like cakes, crackers, biscuits, and pastries. This type of flour has a lower gluten content, making it ideal for creating tender and delicate baked goods.

- Bread Flour:

- Breakfast Foods:

- Cereals:

- Various breakfast cereals are made from wheat, including products like “Shredded Wheat,” “Puffed Wheat,” and “Bran Flakes.” These items often feature whole grain or bran components and serve as nutritious breakfast options.

- Farinas:

- Farinas are a type of processed wheat product used in breakfast foods. They are refined and typically used in hot cereals.

- Cereals:

- Pastes and Noodles:

- Macaroni and Spaghetti:

- For pasta products like macaroni, spaghetti, and noodles, durum wheat semolinas are employed. Semolina is separated from the flour and bran, mixed with water to form dough, and processed through a hydraulic press. This dough is extruded through molds to create various pasta shapes. After extrusion, the pasta is dried at approximately 70°F.

- Noodles:

- Noodles are produced by rolling the dough into thin strips. They are a smaller type of pasta and can vary in thickness and texture.

- Macaroni and Spaghetti:

- Alcohol and Industrial Products:

- Beer and Alcoholic Beverages:

- Wheat is also used in brewing beer and other alcoholic beverages. Special wheat varieties are cultivated for this purpose.

- Industrial Alcohol:

- Wheat is processed to produce industrial alcohol, which has various applications in manufacturing and industry.

- Beer and Alcoholic Beverages:

- Starch Production:

- Starch Extraction:

- Wheat starch is extracted for use in the sizing of textile fibers. This specialized wheat variety is chosen for its high starch content.

- Starch Extraction:

- Straw Products:

- Wheat Straw:

- Wheat straw, known for its strength, is used in a range of applications including seating for chairs, mattress stuffing, and the production of straw carpets, strings, beehives, baskets, and wickerwork.

- Straw Hats:

- In Tuscany, the bearded wheat is used to make Leghorn hats, a type of straw hat.

- Other Uses:

- Wheat straw is also employed in packing materials, thatching, and as fodder and manure. It is valued for its utility in agriculture and various crafts.

- Wheat Straw:

- Text Highlighting: Select any text in the post content to highlight it

- Text Annotation: Select text and add comments with annotations

- Comment Management: Edit or delete your own comments

- Highlight Management: Remove your own highlights

How to use: Simply select any text in the post content above, and you'll see annotation options. Login here or create an account to get started.