- Strongyloides stercoralis is a parasitic roundworm that causes the disease strongyloidiasis in humans. In the United States, it is known as threadworm. However, in the United Kingdom and Australia, threadworm can also refer to nematodes of the genus Enterobius, also known as pinworms.

- Strongyloides stercoralis is capable of human parasitism. The adult parasitic stage inhabits passages in the small intestine’s mucosa.

- Strongyloides contains 53 species, with S. stercoralis serving as the type species. S. stercoralis has been reported in cats and canines, among other mammals.

- However, it appears that the predominant species in canines is not S. stercoralis, but the closely related S. canis. S. fuelleborni and S. cebus are the most common species to infect nonhuman primates, although S. stercoralis has been reported in captive primates.

- S. fuelleborni in central Africa and S. kellyi in Papua New Guinea are additional Strongyloides species that are naturally parasitic on humans but have restricted distributions.

Strongyloides stercoralis

- Strongyloides stercoralis, also known as threadworm, is a soil-transmitted nematode that belongs to the roundworm nematode group.

- Due to the lack of precise data from endemic areas, the global burden of this parasitic infection is still underappreciated, despite the fact that it is nearly ubiquitous, except in the extremes of the north and south.

- S. stercoralis is thus one of the “neglected tropical diseases” (NTDs) parasitic infections that is most neglected.

- The helminth S. stercoralis primarily infects humans, but it is also found naturally in canines, cats, and primates.It is distinguished from other human nematodes by its ability to produce free-living worms from rhabditiform larvae shed in human feces, which then proliferate to produce infective, skin-penetrating filariform larvae in the external environment.

- The clinical manifestations of S. stercoralis infections in humans range from asymptomatic carriers to acute strongyloidiasis and disseminated infections.

- Strongyloidiasis refers to an infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. Its ability to induce overwhelming hyperinfection in immunocompromised individuals distinguishes it from other helminth infections.

- Due to its autoinfection life cycle, a Strongyloides infection can last the lifetime of its host and cause a broad spectrum of diseases, from asymptomatic eosinophilia to severe, life-threatening disseminated disease in immunocompromised patients.

Distribution of Strongyloides stercoralis

- Infection with S. stercoralis is linked to fecal contamination of soil or water. Therefore, it is an extremely uncommon infection in developed economies.

- In developing nations, the disease is less prevalent in cities than in rural areas (where sanitation standards are inadequate). S. stercoralis is prevalent in tropical and subtropical environments.

- Strongyloidiasis was first documented in French soldiers returning from Indochina expeditions in the 19th century. Today, the former countries of Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) continue to have endemic strongyloidiasis, with prevalences of 10% or less.

- Formerly, strongyloidiasis was endemic in certain regions of Japan, but control programs have eradicated the disease.

- Strongyloidiasis seems to be prevalent in certain regions of Brazil and Central America. It is endemic to Africa, but its incidence is typically low (1 percent or less).

- There have been reports of pockets in the countryside of Italy, but the current status is uncertain. Strongyloidiasis is uncommon in the Pacific islands, although some cases have been reported from Fiji.

- Some rural and remote Australian Aboriginal communities in tropical Australia have extremely high rates of strongyloidiasis.

- In the 1970s, S. fuelleborni was more prevalent than S. stercoralis in certain African countries (e.g., Congo), but the current situation is unknown.

- S. stercoralis is endemic in Papua New Guinea, but its prevalence is minimal. In certain regions of the New Guinea Highlands and Western Province, however, another species, S. kellyi[6], is a prevalent parasite of children.

- Knowledge of the geographical distribution of strongyloidiasis is important for travelers who may contract the parasite while visiting endemic regions.

- Because strongyloidiasis could conceivably be transmitted through unsanitary bed linens, hotel guests in endemic areas should never use unclean bed sheets. Traveling to tropical regions may necessitate the use of shower footwear made of plastic.

- Estimates of the number of infected individuals vary, with one estimate placing the number at 370 million globally. In some tropical and subtropical countries, local prevalence can exceed 40%.

Habitat of Strongyloides stercoralis

- Strongyloides stercoralis is a parasitic nematode that infects humans and other animals. Its habitat is primarily in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in areas with poor sanitation and hygiene practices.

- The lifecycle of Strongyloides stercoralis involves two forms of the parasite: the free-living form, which lives in the soil, and the parasitic form, which infects humans and other animals. The infective stage of the parasite, which is called the filariform larvae, can survive in soil for several weeks, particularly in moist and warm conditions.

- Humans and other animals become infected with Strongyloides stercoralis when they come into contact with contaminated soil, usually through their skin. Once inside the body, the larvae migrate to the lungs, where they are coughed up and swallowed. They then travel to the small intestine, where they develop into adult worms and lay eggs.

- Overall, the habitat of Strongyloides stercoralis is closely linked to poor sanitation and hygiene practices, which contribute to the presence of contaminated soil. Measures to improve sanitation and hygiene, such as proper disposal of human waste and improved access to clean water, can help reduce the incidence of infection with this parasite.

Morphology of Strongyloides stercoralis

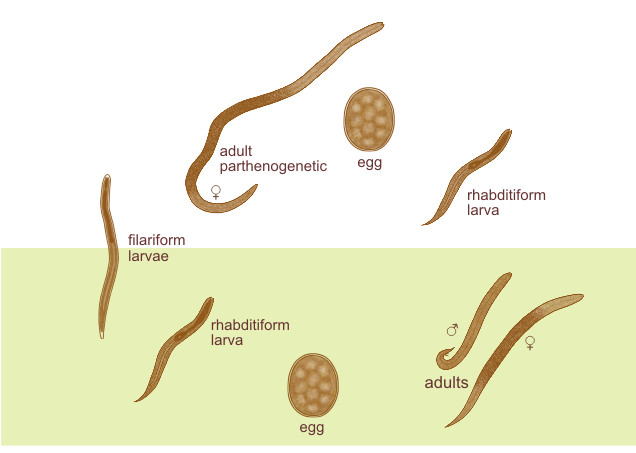

There are two different species of Strongyloides stercolaris: parasitic and free-living. The females are easily found during the parasite phase, but not the males.

Parasitic female

- Strongyloides stercoralis’ female worm is a thin, translucent, cylindrical nematode that is about 2.5 mm long and 40–50 µm wide.

- It has four tiny lips covering its buccal cavity, and the anterior third of its body is taken up by a muscular, cylindrical esophagus.

- The intestines take up the back two-thirds of the body and open ventrally through the anus, which is located just in front of the pointed tip of the tail.

- The reproductive system consists of paired uteri, a vagina, and a vulva, with the vulva being situated at the intersection of the body’s middle and posterior thirds.

- The female, an ovoviviparous species, can lay up to 30 to 40 partially developed eggs every day in the human intestine’s mucosal epithelium.

- The uteri of the gravid female house transparent, ovoid, thin-walled eggs that measure 50 µm by 30 µm in size.

- The average lifespan of a single worm is 3 to 4 months, but because it can lead to autoinfection, the infection can linger for years.

Parasitic males

- Male Strongyloides stercoralis worms are approximately 0.6-1 mm in length and 40-50 μm in breadth, which is shorter and broader than females.

- They remain parasitic in the lumen of the large intestine and lack the ability to penetrate the intestinal wall, so they do not invade it.

- Male parasites are absent from infected humans.

- The males have two spicules that penetrate the female during copulation on their posterior end.

Eggs

- Inside the bodies of pregnant female Strongyloides stercoralis worms are 5 to 10 eggs arranged in a single file.

- The eggs are oval-shaped, have a thin, transparent covering, and measure 55 µm in length and 30 µm in width.

- Every egg contains a ready-to-hatch larva.

- Strongyloides eggs are ovoviviparous, meaning they hatch within the mucosa and emerge as noninfectious rhabdiform larvae in the lumen of the small intestine.

- The larvae are then expelled via feces.

Larva

The larva of S. Stercoratis is of two types:

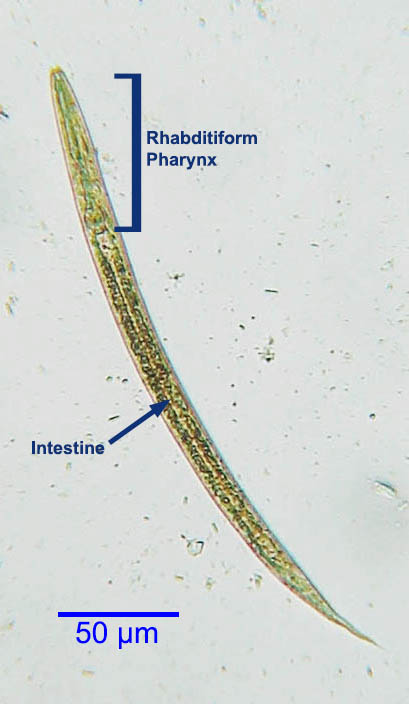

1. Rhabditiform larva (first stage larva)

- The eggs laid by the pregnant female in the small intestinal mucosa hatch promptly into the first-stage larva.

- It has a length of 200-300 µm and a width of 16 µm, and it is actively motile.

- It has a petite mouth, double bulb oesophages, and a genital primordium that is barely noticeable.

- The L1 larva migrates into the lumen of the intestine and travels down the intestine to be expelled in the feces.

- In a warm and humid environment, they mature and become adult male and female worms that live independently.

- It is the most prevalent diagnostic form of the parasite found in human feces, measuring 0.25 mm in length and possessing a relatively short, muscular double bulb esophagus.

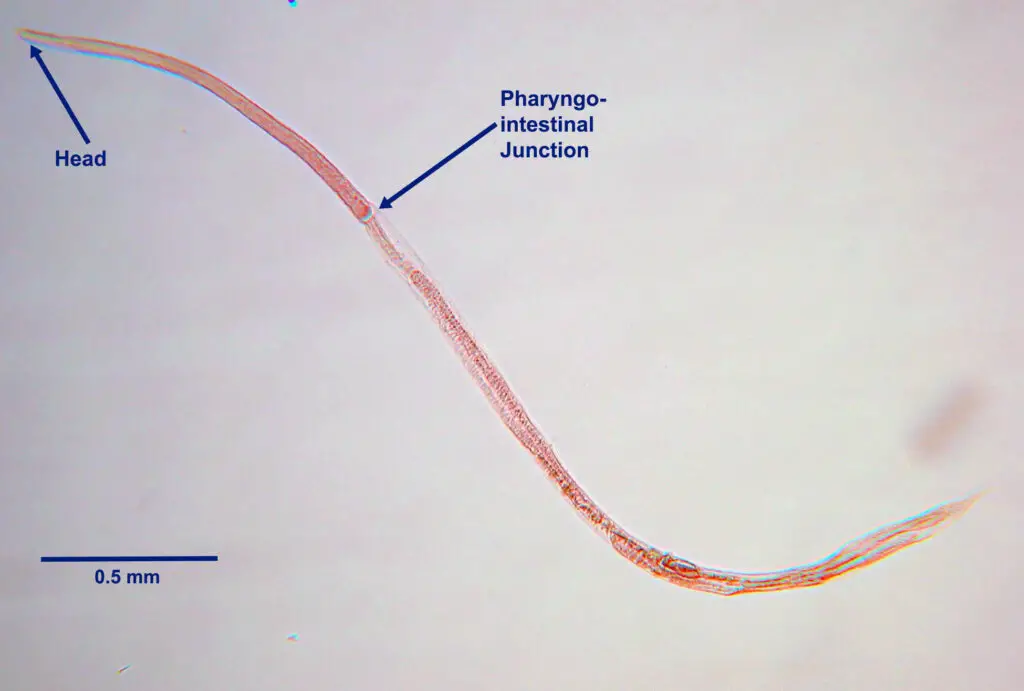

2. Filariform Larva (L3 stage)

- The L1 larva undergoes two molts to become the L3 larva, which is the human-infectious stage of the parasite.

- Long and slender, measuring 630 µm in length and 10 µm in width, L3 larvae have a narrow mouth and a long, cylindrical oesophagus with a notched tail.

- These infectious L3 stages can persist in the environment until a suitable host is encountered.

- Similar to Ancylostoma, they gain access to their host through the epidermis.

Life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis

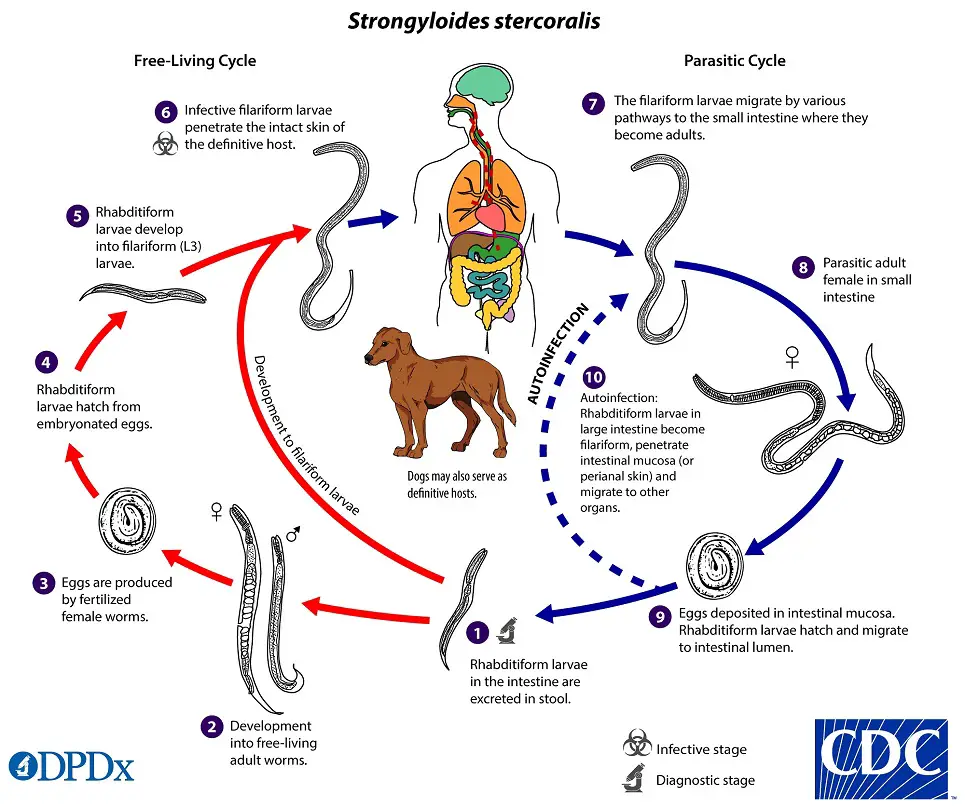

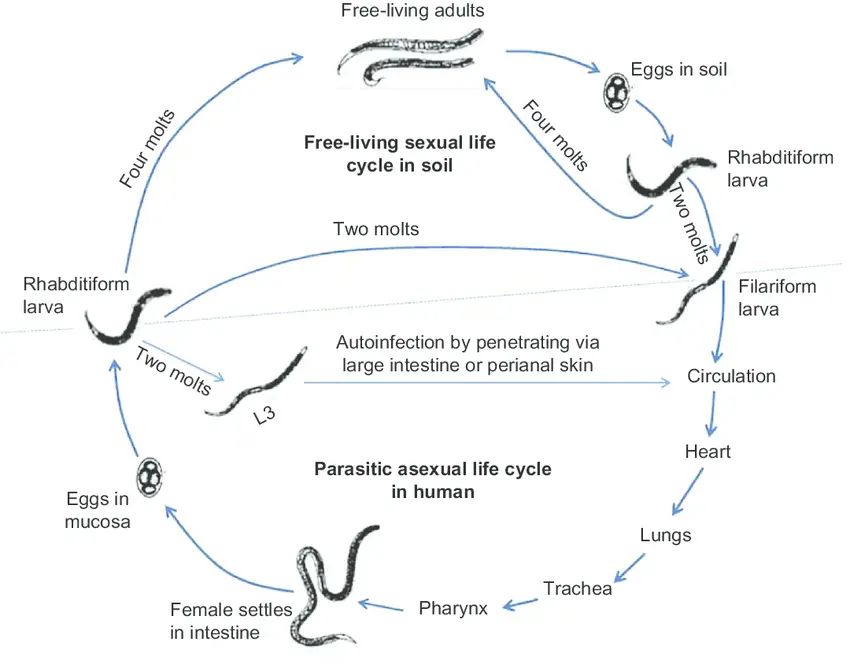

The life cycle of S. stercoralis is complicated due to the multiplicity of possible development routes. It is unique among human nematodes in that it has both a parasitic cycle and a free-living soil cycle, in which it can survive in the soil for extended periods by feeding on soil microbes and passing through multiple generations.

- Natural host: Man, although dogs and cats are found infected with morphologically indistinguishable strains.

- Infective form: Filariform larva.

Strongyloides stercoralis has a complex life cycle that alternates between free-living and parasitic phases and involves autoinfection. In the cycle of autonomous living: Rhabditiform larvae are passed in the stool of an infected definitive host, develop into either infective filariform larvae (direct development) or free-living adult males and females that mate and produce eggs from which rhabditiform larvae hatch and eventually become infective filariform (L3) slarvae. The filarial larvae penetrate the epidermis of the human host to initiate the parasitic cycle (see image below). This generation of filariform larvae cannot develop into adults and must locate a new host in order to continue the life cycle. When human epidermis comes into contact with contaminated soil, filariform larvae penetrate the skin and migrate to the small intestine. The L3 larvae are believed to migrate to the lungs via the bloodstream and lymphatics, where they are eventually coughed up and ingested. Nonetheless, L3 larvae appear capable of migrating to the intestine via alternative pathways (e.g., via abdominal viscera or connective tissue). In the small intestine, larvae undergo two molts and mature into adult female worms. The females reside in the submucosa of the small intestine and produce rhabditiform larvae via parthenogenesis (parasitic males do not exist) image. The rhabditiform larvae can either be discharged in feces (see “Free-living cycle” above) or can cause autoinfection image. Rhabditiform larvae in the intestine metamorphose into infective filariform larvae that can invade either the intestinal mucosa or the skin of the perianal region, causing autoinfection. Once the filariform larvae have reinfected the host, they are transported to the airways, pharynx, and small intestine, or they disseminate throughout the body. Autoinfection in Strongyloides is significant because untreated cases can result in persistent infection, even after decades of residence in a nonendemic area, and may contribute to the development of hyperinfection syndrome.

Mode of infection

The primary source of infection is feces-contaminated soil. Skin penetration by the L3 larva (while strolling barefoot). The emission of hydrolytic enzymes by larvae aids in penetration. Autoinfection (autoinfection internal).

By transplanting kidneys and other organs into a new host. Although uncommon, additional transmission routes for the larva have been reported, including in utero, transmammary, and zoonotic transmission.

The life cycle of S. stercoralis is complicated due to the multiplicity of possible development routes. It is unique among human nematodes in that it has both a free-living soil cycle and a parasitic cycle, in which it can survive in soil for extended periods by feeding on soil microbes and passing through multiple generations.

1. Free-living soil cycle

- In humans, the life cycle is concluded in a single host.

- Due to the propensity for autoinfection and multiplication within infected hosts, the life cycle is distinctive.

- The parasite demonstrates two discrete life cycles, one within the human body and another in the soil.

a. Direct Development

- Upon reaching the soil, the rhabdiform larva undergoes two moults to transform into the infective filariform larva (L3) within three to four days.

- The L3 larva functions as the infectious form and infects humans via skin penetration.

b. Indirect Development

- Within twenty-four to thirty hours, the rhabditiform larva’s feces transforms into free-living adult males and females in moist soil.

- Adult worms mate, and the female produces eggs with embryos.

- The egg will soon emerge to release the next generation of rhabdiform larvae (L1), which undergo two molts to develop into infective L3 filariform larvae.

- The filariform larvae penetrate intact epidermis, triggering the parasitic phase of the infection.

2. Parasitic cycle

- After penetrating the epidermis, filariform larvae (L3) travel through the lymphatics or venules to the right side of the heart and then to the lungs via pulmonary circulation.

- In the lungs, the larvae invade the alveoli, migrate up the tracheobronchial tree, and then, after ingesting sputum, reach the gastrointestinal tract.

- In the proximal small intestine, the larvae undergo two metamorphoses and develop into adult female worms that produce ova through parthenogenesis (parasitic males do not exist).

- Adult female roundworms reside in the submucosal tissues of the small intestine.

- Approximately 25 to 30 days after the initial penetration of the skin, the production of eggs commences.

- The rhabditiform larvae promptly hatch and enter the lumen of the intestine. They are excreted in the feces (free-living cycle), thereby reiterating the life cycle. or can cause autoinfection.

Autoinfection

- Some rhabditiform larvae transform into filariform larvae within the intestinal lumen. These newly hatched larvae can then invade the intestinal mucosa or perineal tissue to complete the cycle of autoinfection. This enables the organism to maintain the infection within the host.

- Autoinfection is typically restricted by a healthy immune response. However, even in immunocompetent hosts, a low level of autoinfection can occur, leading to decades-long chronic infections that may only manifest clinically in the presence of immunosuppression.

Hyperinfection

- The hyperinfection syndrome is the disease’s most severe manifestation, with a high mortality rate. This occurs in chronically infected individuals who develop immunosuppression and in acutely infected patients with immunosuppression.

- It is caused by uncontrolled and accelerated autoinfection, which leads to the dissemination of larvae to end organs such as the liver and brain. In patients with hyperinfection syndrome, bacterial translocation from the intestinal wall is a frequent cause of sepsis.

Pathogenesis and Clinical features of Strongyloides stercoralis

Strongyloidiasis is typically asymptomatic, particularly in immunocompetent individuals. Unexplained peripheral eosinophilia is frequently the only sign of infection. Some studies report that over fifty percent of affected patients exhibit nonspecific symptoms.

Acute Infection

- Acute infection may manifest as an itchy, serpiginous rash where the larvae have penetrated the epidermis. When filariform larvae from fecally contaminated soil penetrate the epidermis and enter the body, there is intense itching, congestion, and edema at the site of entry.

- This condition is known as ground itch and typically affects the feet or palms, but can also occur in the perineum, abdomen, or virtually anywhere else on the body. This severe urticaria may last up to three weeks.

- Intradermal migration is extremely rapid (five to fifteen centimeters per hour), and the rash it induces is called larva currens.

- Larva currens, also known as “running” larva, is a pathognomonic dermatologic manifestation of strongyloidiasis and can also be observed in cases of autoinfection. Larva currens manifests as a raised, pink, itchy, serpiginous stripe that can advance between 5 and 15 centimeters per hour.

- Passage of the larvae through the airways may result in a dry cough and a syndrome resembling Loeffler characterized by dyspnea, wheezing, eosinophilia, and migratory pulmonary infiltrates. The larvae enter the pulmonary circulation via venules and lymphatics, causing pulmonary hemorrhages and dyspnea. Frequently, eosinophilic infiltration of the alveolar spaces is accompanied by pneumonitis.

- Symptoms of the digestive tract include diarrhea, vomiting, and epigastric discomfort.

- The hyperinfection syndrome is characterized by fever, gram-negative bacteremia, and sepsis with end-organ dysfunction (hemoptysis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, ileus, hyponatremia).

Chronic Infection

- Strongyloides stercoralis is also capable of causing chronic infections in humans that can last for years. Chronic infections with Strongyloides stercoralis cause cough, rhonchi, dyspnea, abdominal pain, anorexia, diarrhea, and/or constipation.

- In chronic forms, respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms are typically moderate, and dermatologic manifestations such as urticaria and larva currents are still present.

Chronic Infection

- The accelerated autoinfection of the parasite within the host causes hyperinfection, which results in a high parasite burden and severe disease.

- Similar signs and symptoms accompany hyperinfection and increased larval migration within the organs.

- With hyperinfection syndrome, larvae migrate to distant organs such as the liver, pancreas, kidneys, mesenteric lymph nodes, brain, and skeletal muscles, causing disseminated disease.

Laboratory diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis

Laboratory diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection involves several methods that can be used alone or in combination, including:

- Stool examination: The identification of Strongyloides larvae in stool samples is the most common diagnostic method for strongyloidiasis. The larvae are usually small and thin, measuring about 200 to 300 µm in length and 10 to 20 µm in width. Stool samples should be collected on three consecutive days to increase the sensitivity of the test.

- Serological tests: Various serological tests are available for detecting antibodies to Strongyloides in blood samples. These tests include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), and Western blot. However, these tests may give false-negative results in patients with low antibody levels or chronic infections.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): PCR is a highly sensitive and specific method for detecting Strongyloides DNA in stool samples. This method can detect low levels of infection and differentiate between different species of Strongyloides.

- Larval culture: This method involves culturing Strongyloides larvae from stool samples on a special agar medium. It can be used to confirm the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis and to differentiate between S. stercoralis and other related parasites.

It is important to note that the symptoms listed in the question are not specific to Strongyloides infection and can be caused by a variety of other conditions. Therefore, laboratory diagnosis is essential to confirm the presence of Strongyloides and rule out other possible causes of the symptoms.

Treatments of Strongyloides stercoralis infections

The treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection involves the use of anthelmintic drugs to kill the parasites. The choice of drug and the duration of treatment depend on the severity of the infection and the presence of any underlying medical conditions.

The drugs commonly used to treat Strongyloides infection include:

- Ivermectin: This drug is the treatment of choice for Strongyloides infection. It is a broad-spectrum antiparasitic agent that kills both the adult worms and the larvae. The usual dose is 200 micrograms per kilogram of body weight per day for two days.

- Albendazole: This drug is also effective against Strongyloides infection, although it is not as effective as ivermectin. The usual dose is 400 milligrams twice daily for three days.

- Thiabendazole: This drug was used in the past to treat Strongyloides infection but is now less commonly used due to its side effects and lower efficacy compared to the other two drugs. The usual dose is 25 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per day for five days.

In addition to drug treatment, supportive care may be needed for patients with severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or hypotension. Patients with hyperinfection syndrome or disseminated infection may require hospitalization and intensive care.

It is important to note that in patients with chronic or asymptomatic Strongyloides infection, treatment may need to be repeated periodically to prevent the development of hyperinfection syndrome or disseminated infection.

Prophylaxis of Strongyloides stercoralis

The prophylaxis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection involves identifying and treating individuals at high risk of infection. The high-risk groups include:

- Individuals living or traveling in endemic areas: Strongyloides infection is common in tropical and subtropical regions, including parts of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific Islands. Travelers to these regions should be advised to take precautions to prevent infection, such as avoiding walking barefoot, drinking untreated water, or eating raw or undercooked foods.

- Immunosuppressed individuals: Strongyloides infection can cause severe disease in individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS, organ transplant recipients, or those receiving chemotherapy. These individuals should be screened for Strongyloides infection and treated if necessary.

- Individuals with chronic respiratory or gastrointestinal diseases: Chronic respiratory or gastrointestinal diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or inflammatory bowel disease, can increase the risk of Strongyloides infection. These individuals should be screened for Strongyloides infection and treated if necessary.

The prophylactic measures for Strongyloides infection include:

- Screening: Screening for Strongyloides infection should be performed in individuals at high risk, using stool examination or serological tests.

- Treatment: Individuals found to be infected with Strongyloides should be treated with anthelmintic drugs, such as ivermectin or albendazole, to prevent the development of hyperinfection syndrome or disseminated infection.

- Education: Individuals at high risk should be educated about the transmission of Strongyloides infection and advised to take precautions to prevent infection, such as wearing shoes, using safe drinking water, and cooking food thoroughly.

- Environmental measures: Environmental measures, such as improving sanitation and hygiene, can also help prevent Strongyloides infection in endemic areas.

FAQ

What is Strongyloides stercoralis, and how is it transmitted?

Strongyloides stercoralis is a parasitic roundworm that infects humans. The infection is usually acquired by skin penetration of the infective larvae present in contaminated soil, but it can also be acquired by ingestion of contaminated food or water.

What are the symptoms of Strongyloides stercoralis infection?

Many people with Strongyloides stercoralis infection have no symptoms. However, some may experience itching, rash, diarrhea, abdominal pain, cough, and shortness of breath.

How is Strongyloides stercoralis infection diagnosed?

Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection is made by identifying the larvae in stool samples or by serological tests that detect antibodies to the parasite.

What is the treatment for Strongyloides stercoralis infection?

The treatment for Strongyloides stercoralis infection involves the use of anthelmintic drugs, such as ivermectin or albendazole.

Can Strongyloides stercoralis infection be prevented?

Strongyloides stercoralis infection can be prevented by practicing good personal hygiene, avoiding contact with contaminated soil, and drinking safe water.

Is Strongyloides stercoralis infection contagious?

Strongyloides stercoralis infection is not contagious from person to person. It is only acquired from contaminated soil, food, or water.

Can Strongyloides stercoralis infection be fatal?

In healthy individuals, Strongyloides stercoralis infection is usually not fatal. However, in individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or receiving chemotherapy, the infection can be life-threatening.

What is hyperinfection syndrome, and how is it treated?

Hyperinfection syndrome is a severe form of Strongyloides stercoralis infection that occurs when the larvae multiply excessively in the body. It can lead to sepsis and organ failure. Treatment involves high-dose anthelmintic drugs and supportive care.

Can Strongyloides stercoralis infection be chronic?

Yes, Strongyloides stercoralis infection can be chronic, lasting for years or even decades, especially in individuals with a weakened immune system.

Is there a vaccine available for Strongyloides stercoralis infection?

No, there is no vaccine available for Strongyloides stercoralis infection. The best way to prevent infection is to practice good personal hygiene and avoid contact with contaminated soil, food, or water.

References

- Viney ME, Lok JB. The biology of Strongyloides spp. In: WormBook: The Online Review of C. elegans Biology [Internet]. Pasadena (CA): WormBook; 2005-2018. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19795/

- Mora Carpio AL, Meseeha M. Strongyloides Stercoralis. [Updated 2023 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436024/

- https://www.biologydiscussion.com/medical-parasitology/class-nematoda-strongyloides-stercoralis-thread-worm/31213

- https://www.biologydiscussion.com/parasitology/parasitic-worm/life-cycle-of-roundworm-with-diagram/62260

- https://www.slideshare.net/MizanRahman9/strongyloides-stercoralis-63214733

- https://universe84a.com/strongyloides-stercoralis/

- https://www.uomus.edu.iq/img/lectures21/MUCLecture_2022_122620428.pdf

- http://nemaplex.ucdavis.edu/Taxadata/Sstercoralis.htm

- https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/strongyloides/biology.html

- https://www.onlinebiologynotes.com/strongyloides-stercoralis-morphology-life-cycle-pathogenesisdiseases-diagnosis-and-treatment/

- https://wcvm.usask.ca/learnaboutparasites/parasites/strongyloides-stercoralis.php