What is Fusarium Wilt?

Fusarium wilt is a prevalent soil-borne fungal affliction produced by Fusarium oxysporum, affecting various plants such as tomatoes, bananas, cucumbers, and beans, resulting in progressive wilting and eventual plant mortality.

- F. oxysporum appears in specialised forms known as formae speciales, each tailored to infect certain host plants, exhibiting pronounced host specificity, hence complicating control measures.

- Symptoms – initial wilting manifests during the hottest portions of the day, followed by leaves transitioning from yellow to brown, ultimately leading to plant collapse, frequently without discernible external indicators in the early stages.

- Vascular damage occurs when fungus infiltrates xylem vessels, resulting in black discolouration observable upon stem incision, obstructing water delivery and leading to swift wilting and mortality.

- Infection occurs when fungi penetrate primarily through root injuries resulting from mechanical damage, nematode feeding, or contaminated instruments, hence increasing the susceptibility of compromised roots.

- existence It generates robust spores known as chlamydospores that endure in soil for years without host plants, complicating eradication efforts and rendering replanting precarious.

- Optimal conditions—warm, moist soils with temperatures ranging from 27 to 32°C and a slightly acidic pH—promote fungus proliferation and disease progression, heightening risk in numerous areas.

- Control methods—crop rotation with non-hosts, employing resistant cultivars, sanitising tools, and preventing root injuries during cultivation—are essential tactics; nevertheless, none are wholly effective in isolation.

- The establishment of resistant cultivars of plant varieties against specific F. oxysporum races mitigates losses; nevertheless, this resistance may deteriorate over time due to fungal evolution.

- Biological control – some biocontrol agents, such as Trichoderma spp., are employed to mitigate pathogen populations in soil, demonstrating potential but not yet serving as a singular solution.

- The economic impact results in substantial yield loss; for instance, tomato harvests in certain Indian regions have recorded losses of up to 45%, adversely hurting farmers’ income and food supply.

- The global dissemination of disease poses a significant concern, particularly to banana cultivation, with Cavendish bananas being severely impacted by Panama disease, a variant of Fusarium wilt.

- Fungicide limitations – chemical control is largely ineffectual due to the fungus residing within plant vessels and soil, necessitating integrated management.

- Prevention—utilizing disease-free seeds, ensuring soil sanitation, refraining from planting in contaminated soils, and meticulously monitoring crop health are essential to mitigate spread and losses.

- The study focus include ongoing investigations designed to enhance comprehension of pathogen biology, elucidate host resistance mechanisms, and devise enhanced control strategies, including genetic and biocontrol approaches.

Causative Agent of Fusarium Wilt

Primary causal organism – Fusarium oxysporum is the dominant species responsible for Fusarium wilt across diverse hosts

Formae speciales (f. sp.) – specialized strains target specific hosts

- f. sp. lycopersici – infects tomato

- f. sp. vasinfectum – infects cotton

- f. sp. cubense – causes Panama disease in banana

- f. sp. pisi – infects peas

- f. sp. lentis – infects lentils

- f. sp. capsici – infects pepper

Other Fusarium spp. involved – some wilt cases are linked to non-oxysporum species

- Fusarium solani species complex (FSSC) – infects melon, cauliflower

- Fusarium verticillioides – causes wilt in guava, pepper

- Fusarium falciforme – affects guava, tomato

- Fusarium equiseti – involved in chickpea infections

- Fusarium udum – major wilt agent in pigeonpea

- Fusarium sacchari – wilt in sugarcane

- Fusarium asiaticum – seedling rot in Hinoki cypress

Hosts of Fusarium oxysporum

Fusarium oxysporum infects a very broad range of plants, over 120 species across many families, including economically important crops like banana, tomato, cotton, legumes, onion, sweet potato, cucurbits, tobacco, and ornamentals.

Common hosts – tomato, tobacco, legumes (beans, peas, peanuts), cucurbits (melon, cucumber, watermelon), sweet potato, cotton, banana, spinach, beet, onion, asparagus, cannabis, date palm, strawberry, orchid, tulip.

- Solanaceae hosts – tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), potato (S. tuberosum), pepper (Capsicum annuum), cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana)

- Fabaceae hosts – lentil (Lens culinaris), pea (Pisum sativum), chickpea (Cicer arietinum), several Acacia spp. including A. mangium, A. crassicarpa, A. auriculiformis

- Cucurbitaceae hosts – cucumber (Cucumis sativus), melon (C. melo), watermelon; mainly targeted by f. sp. cucumerinum, f. sp. melonis

- Musaceae host – banana (Musa spp.), highly susceptible to f. sp. cubense, especially Tropical Race 4 (TR4)

- Other Hosts

- Cotton host – Gossypium spp., vascular wilt and root decay common

- Strawberry host – Fragaria × ananassa, often exhibits vascular necrosis, wilt

- Coffee host – Coffea arabica, leaf wilt and shoot dieback observed

- Soybean host – Glycine max, blighted leaves and wilted stems typical

- Tobacco host – Nicotiana tabacum, yellowing, drying, systemic collapse

- Coriander host – Coriandrum sativum, leaf chlorosis, wilting symptoms

- Chinese yam host – Dioscorea polystachya, stem necrosis and leaf death

- Date palm host – Phoenix dactylifera, tip-to-base leaflet drying pattern

- Safflower host – vascular wilt, rapid leaf collapse

- Lucky bamboo host – Dracaena sanderiana, basal stem rot and wilt

- Pennisetum sinese host – stem discoloration, foliar blight

- Gleditsia sinensis host – vascular discoloration, plant drying

- Bletilla striata host – leaf curling, necrotic streaks, root infection

- Lettuce host – Lactuca sativa, vascular browning, plant wilting

- Dianthus carthusianorum host – root and leaf rot, stem lesions

- Dinteranthus vanzylii host – leaf shriveling, necrosis, tissue rot

- Eurycoma longifolia host – affected by vascular wilt

- Arabidopsis thaliana – widely used as model host in pathogenesis studies

Symptoms of Fusarium Wilt

General Symptoms

- Wilting – typically begins in older leaves, can be partial or affect whole plant

- Leaf chlorosis – yellowing starts in lower leaves, spreads upwards

- Leaf necrosis – browning, death of tissue, margins dry, leaf curl common

- Vascular discoloration – brown or reddish streaks in xylem, diagnostic feature

- Root rot – decay, blackening, reduced branching, soft tissue collapse

- Stem lesions – necrotic patches near soil line, dark sunken spots

- Stunting – poor growth, reduced height, weak shoots

- Plant death – occurs in advanced infection stages, rapid collapse in some hosts

- Date palm – leaflet whitening, midrib remains green, tip-to-base drying

Host-Specific Symptoms

- Cotton – root rot, dark vascular streaks, leaf droop

- Strawberry – wilted foliage, dark bundles, tiny deformed fruits

- Melon (Manis Terengganu) – sudden wilting, brown stem base

- Chinese yam – dried crown leaves, brown basal stem streaks

- Potato – foliage wilt, vascular browning, yield loss

- Sea buckthorn – extensive chlorosis, stem shrivel

- Pepper – top leaves wilt, black stem patches expand upward

- Cucumber – yellow leaves, wilting, xylem streaks, quick death

- Coriander – yellowing, whole-plant collapse

- Coffee – limp foliage, twig death

- Soybean – wilted shoots, scorched margins

- Tobacco – yellow, curled, dead leaves

- Geranium – internal xylem turns brown, leaf pale

- Common bean – dwarf growth, yellow curling leaves

- Peanut – base rot, midrib bleaching, death

- Safflower – sudden wilt, no recovery

- Lucky bamboo – soft rot at stem base, collapse

- Pennisetum sinese – leaf drying, black stem inside

- Gleditsia sinensis – total leaf wilt, brittle stem

- Bletilla striata – curled brown tips, brown vascular streaks

- Lettuce – central wilt, xylem turns rusty

- Carthusian pink – yellow-brown stem base, rotted roots

- Dinteranthus vanzylii – soft rotted leaves, white mold, dead tissue

Etiology of Fusarium Wilt

Environmental conditions – disease severity increases in warm, moist soils

- grows best at 24°–30°C

- thrives in poorly drained soils, restricted water flow enhances spread through vascular bundles

Host-specific interactions – each forma specialis infects particular plant species

- f. sp. lycopersici – infects tomato

- f. sp. cubense – infects banana

- interaction depends on genetic compatibility of both host and pathogen

Virulence factors – Fusarium spp. produce multiple agents enhancing pathogenicity

- cell wall–degrading enzymes

- host-targeting toxins damaging organelles

- inhibitory proteins suppressing plant defense mechanisms

Genetic variability – Fusarium species exhibit high mutation rates and genome plasticity

- adapts rapidly to host resistance

- survives fluctuating environmental conditions

- complicates control and resistance breeding efforts

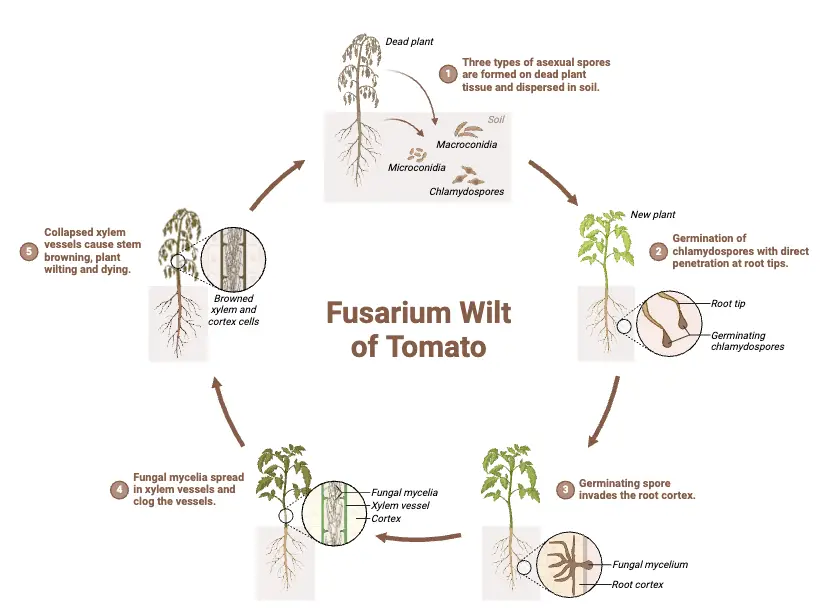

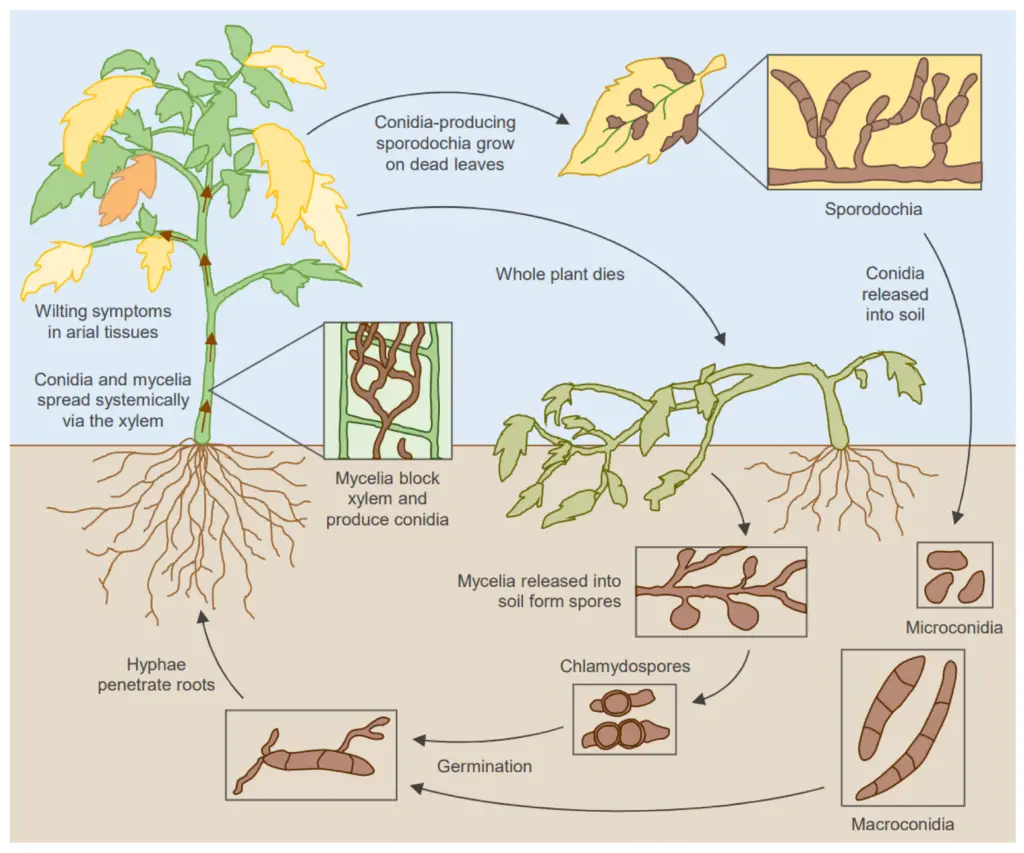

Disease Cycle of Fusarium Wilt

- Survival structures – Fusarium oxysporum persists in soil or plant debris as chlamydospores, macroconidia, microconidia or mycelium; chlamydospores remain viable for many years.

- Initial inoculum – spores or mycelium in soil from infected residues, contaminated tools, seed or propagation materials

- Spore germination trigger – root exudates of a susceptible host stimulate germination of chlamydospores and infection hyphae formation

- Root invasion – hyphae penetrate root epidermis at root tips or wounds, then advance intercellularly through cortex toward vascular tissue.

- Vascular colonization – fungus enters xylem, produces micro‑ and macroconidia; spreads upward via sap stream, blocks vessels and disrupts water transport.

- Symptom development – blockage causes leaf chlorosis, wilting (often starting on one side), necrosis, stunting, eventual plant collapse.

- Secondary sporulation – on dead or decaying tissue, macroconidia and chlamydospores formed, replenishing soil inoculum

- Dispersal mechanisms – spread via water splash, contaminated soils, tools, transplants, seed; rare airborne dispersal; possibly insect vectors facilitate long‑distance movement

- Single cycle per season – primary infection occurs once per crop season; infected plants rarely initiate new infections same season .

Diagnosis of Fusarium Wilt

- Visual field diagnosis – look for symptom pattern: wilting during hot hours, yellowing often unilateral, vascular browning in stem’s center visible when peeled or sliced open.

- Stem cut assay – longitudinal stem cut above soil line; dark red‑brown xylem staining suggests Fusarium wilt rather than phloem diseases like viruses.

- Culture-based isolation – isolate fungus on selective media; F. oxysporum forms white to pink, purple or red colonies; identification via colony morphology and spore observations (micro/macroconidia, chlamydospores). examine microconidia shape and arrangement, and apical cell features for species-level ID.

- Immunological detection – utilize monoclonal antibodies (MoAb) in assays such as tissue‑blot IBA (DT‑IBA) or GP‑IBA; gives positive reaction in infected tissue or soil within ~4 hours. immunofluorescence assay (IFA) with FITC‑linked antibodies enables visualization of F. oxysporum in plant tissues.

- Molecular diagnostics – PCR, real‑time PCR and LAMP assays targeting formae speciales‑specific genes; highly specific and rapid (e.g. LAMP assay for f. sp. ciceris detects target in ≤13 min at sensitivity >0.009 ng/µl).

- Spectroscopy methods – Raman spectroscopy can non‑destructively detect F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense in banana at early asymptomatic stage (~40 days post‑inoculation) with near‑100% accuracy using specific vibrational bands .

- Pathogenicity and race testing – pathogenicity assays on differential host cultivars and PCR with race‑specific primers help confirm forma specialis and race identity .

- Confirmatory external diagnostics – samples should be submitted to professional diagnostic labs (e.g. extension clinics) because symptoms may mimic Verticillium wilt or other disorders; soil tests alone are inadequate for race-level confirmation.

How to prevent Fusarium wilt

- Sanitation and hygiene – remove and destroy infected plant debris; thoroughly clean tools, containers, and machinery to prevent spread.

- Use disease‑free propagation – purchase or use clean seeds, transplants, or propagation material; treat seeds or bulbs with heat or fungicide dips .

- Resistant cultivars – plant varieties bred for resistance to specific formae speciales (e.g., Fol‑resistant tomatoes, Nufar basil resistant to F. oxysporum f. sp. basilicum) .

- Crop rotation and host exclusion – avoid planting susceptible hosts in the same soil for 3–7 years; manage weeds that may serve as reservoirs

- Soil conditioning and irrigation management – ensure well‑drained soils or raised beds; avoid overwatering and waterlogging; avoid flood irrigation and excessive nitrogen, especially ammonium‑based fertilizers

- Adjust soil pH – liming acidic soils to pH 6.5–7.0 can suppress pathogen activity and reduce disease severity.

- Soil treatments – use solarization or heat treatments under clear plastic to reduce soil inoculum; chemical fumigation with methyl bromide or other fumigants has limited duration of effectiveness.

- Biological control – utilize antagonistic microbes such as Trichoderma harzianum (e.g. Trianum products), or plant growth‑promoting rhizobacteria like Bacillus and Pseudomonas, to compete with Fusarium in the rhizosphere .

- Natural plant extracts – soil or foliar applications of neem, clove, aloe vera, or cinnamon leaf extracts have shown suppression of conidia and fungal growth in lab tests.

- Monitor and early removal – scout regularly for early wilting or chlorosis; promptly uproot and destroy symptomatic plants before spread occurs.

Fusarium wilt Mind Map/Cheatsheet

Here is the free mind map/cheatsheet on Fusarium wilt, it will help you to remember the concept

- Pérez-Vicente, Luis F. & Dita, Miguel & Martinez de la Parte, Einar. (2014). Technical Manual Prevention and diagnostic of Fusarium Wilt (Panama disease) of banana caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense Tropical Race 4 (TR4).

- Basal rot Fusarium oxysporum Tomato Koppert. (n.d.). Koppert US. https://www.koppertus.com/disease-control/fusarium-wilt/

- Jackson, E., Li, J., Weerasinghe, T., & Li, X. (2024). The Ubiquitous Wilt-Inducing Pathogen Fusarium oxysporum—A Review of Genes Studied with Mutant Analysis. Pathogens, 13(10), 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13100823

- Fusarium Wilt / Floriculture and Ornamental Nurseries / Agriculture: Pest Management Guidelines / UC Statewide IPM Program (UC IPM). (n.d.). https://ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/floriculture-and-ornamental-nurseries/fusarium-wilt/#gsc.tab=0

- Fusarium Wilt control. Ideas and steps taken. (n.d.). Houzz. https://www.houzz.com/discussions/2180561/fusarium-wilt-control-ideas-and-steps-taken

- What are the best biological ways to control invasive isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici on tomato plants? | ResearchGate. (n.d.). ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/post/What-are-the-best-biological-ways-to-control-invasive-isolates-of-Fusarium-oxysporum-f-sp-lycopersici-on-tomato-plants

- Listing, K. (2024, February 9). Measures to control fusarium wilt in tomato. Katyayani Krishi Direct. https://katyayanikrishidirect.com/blogs/news/control-to-fusarium-wilt-in-tomato?srsltid=AfmBOoofeJ98jb42y7NFCwWn8EGn1rTMH62hIjy2qY-0mwzfG7z6XTvL

- Arborist, C. (2025, March 27). Fusarium wilt treatment: How to prevent and manage this dangerous plant disease. Tree Doctor. https://www.treedoctorusa.com/fusarium-wilt-treatment-prevent-and-manage-plant-disease/

- Cherlinka, V. (2025, July 16). Fusarium wilt: How to prevent and control its spread. EOS Data Analytics. https://eos.com/blog/fusarium-wilt/

- Ajmal M, Hussain A, Ali A, Chen H, Lin H. Strategies for Controlling the Sporulation in Fusarium spp. J Fungi (Basel). 2022 Dec 21;9(1):10. doi: 10.3390/jof9010010. PMID: 36675831; PMCID: PMC9861637.

- Ajilogba CF, Babalola OO. Integrated management strategies for tomato Fusarium wilt. Biocontrol Sci. 2013;18(3):117-27. doi: 10.4265/bio.18.117. PMID: 24077535.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025, July 2). Panama disease. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panama_disease

- Managing Pests in Gardens: Diseases: Fusarium Wilt—UC IPM. (n.d.). https://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/GARDEN/PLANTS/DISEASES/fusariumwlt.html

- Effective strategies for fusarium wilt treatment in your garden. (n.d.). https://www.novobac.com/fusarium-wilt-treatment/

- Fusarium wilt. (n.d.). UMN Extension. https://extension.umn.edu/disease-management/fusarium-wilt

really helpful info, made the topic easy to get.