What is Dutch elm disease (DED)?

A deadly fungal disease that infects elm trees and stops water from flowing through their vessels, causing them to wilt and die. The main cause is Ophiostoma ulmi and Ophiostoma novo-ulmi.

Dutch phytopathologists Schwarz and Buisman found it in the Netherlands in the early 1920s. It was brought to Europe and North America by accident from Asia in the early to middle 1900s.

Spread mainly by elm bark beetles that move spores between trees, but also by root grafts between elms that are next to each other and share underground connections.

The fungus gets into the xylem, and the tree tries to block the vessels with gum and tyloses. This, however, cuts off the tree’s water and nutrient supply, which kills it.

Symptoms include wilting leaves on upper branches that turn yellow or gray-green and then brown (“flagging”), brown streaks that can be seen under the bark, and death can happen within weeks of the first signs.

Impact- very bad; millions of elms died in Europe and North America from the middle of the 20th century onward, with American elm being hit the hardest. By the 1980s, losses in North America were more than 75%.

All Ulmus species are vulnerable, but American elm (Ulmus americana) is the most vulnerable. Asian elms (like U. pumila) are more resistant.

Control strategies include cutting down and removing infected trees, injecting fungicides (like Arbotect and propiconazole) into valuable trees, and using a biological vaccine (Dutch Trig) to make some trees resistant.

Hybrid elm cultivars like “Princeton,” “Valley Forge,” “New Harmony,” and “Sapporo Autumn Gold” were made using Asian species that are resistant to disease to make them more tolerant.

Causal organism of Dutch elm disease

Here are the main causal organisms of Dutch elm disease (DED):

- Ophiostoma ulmi - the original causative fungus responsible for the first pandemic in the early 1900s, native probably to Asia, introduced into Europe and North America

- Ophiostoma novo‑ulmi - a more aggressive, virulent species that largely replaced O. ulmi during the second pandemic from the 1940s onward and is the dominant modern pathogen causing DED

- Ophiostoma himal‑ulmi - a third species native to the western Himalayas, less widespread but recognized as one of the causal agents of DED

Morphology of pathogen (Ophiostoma spp.)

Here’s the morphology of Ophiostoma species (DED pathogens):

- General fungal nature - ascomycete genus featuring dimorphic growth forms, with yeast‑like phase and filamentous hyphae phase in both O. ulmi and O. novo‑ulmi it incl. synnemata, perithecia, conidia formation in host tissue.

- Hyphae and mycelium - produce multicellular filamentous hyphae forming mycelial colonies in xylem vessels this allows lateral and vertical spread within the tree’s vascular system .

- Conidia (asexual spores) - colourless, sticky synnemata‑borne conidia (koremien) produced on dying or dead wood surfaces, adhesive to beetles enabling vector transmission into new trees.

- Perithecia (sexual fruiting bodies) - flask‑shaped, dark perithecia with elongated necks vary by species

- O. ulmi perithecia ~100–150 µm diameter, neck length ~280–420 µm, neck base ~18–42 µm, tip ~11–16 µm (length/base ratio ~2.4–3.5)

- O. novo‑ulmi perithecia ~75–140 µm, neck length ~230–640 µm, base ~19–36 µm, tip ~9–14 µm (ratio ~1.5–6.2)

- Dimorphism regulation - morphological switch from yeast‑cell form to hyphal form regulated by nutrient status, inoculum density, quorum sensing mechanisms and molecular signals like cAMP and Ca²⁺‑calmodulin; genes COL1 and others control dimorphism and sporulation.

- Special structures - capable of forming synnemata (aggregated conidiophores) producing synnematospore chains and perithecia in sexual stage; hydrophobin toxin cerato‑ulmin secreted as part of fungal surface structures and contributes to pathogenicity

Trees affected by Dutch elm disease

Highly susceptible species - American elm (Ulmus americana) regarded as the most vulnerable in N. America, heavy mortality observed across cities.

Other North American species - winged elm (U. alata), rock elm (U. thomasii), red or slippery elm (U. rubra) listed as highly susceptible to DED.

Intermediate susceptibility species - cedar elm (U. crassifolia), European field elm (U. minor or U. carpinifolia), and wych elm (U. glabra) show moderate susceptibility.

European species severely impacted - English elm (U. procera), field elm (U. minor), wych elm (U. glabra) all heavily decimated, especially English elm – beetle‑favoured and widely lost.

Resistant or less susceptible species - Asian species such as Siberian elm (U. pumila), Chinese elm (U. parvifolia), Japanese elm (U. davidiana var. japonica) show higher tolerance and are used in breeding programs.

Related genera susceptibility - species of the genus Zelkova, related to Ulmus, also can be infected by Ophiostoma novo-ulmi.

What are the Symptoms of Dutch elm disease?

The fungus Ophiostoma novo-ulmi causes Dutch elm disease (DED), which shows up as various distinct symptoms:

- Flagging - sudden wilting or drooping of leaves on one branch or limb, often first sign of DED.

- Leaf colour changes - leaves turn dull grey‑green or yellow, then brown and curl, may become dry and brittle, fall prematurely.

- Premature defoliation - leaves shed before normal autumn timing, strewn beneath canopy in spring or summer.

- Branch dieback - affected shoots die back from tips, sometimes forming downward curving “shepherd’s crooks”

- Vascular streaking - brown, blue or grey streaks run parallel to grain in sapwood when bark peeled

- Symptom progression - begins on upper crown branches then spreads downward toward trunk, whole tree may wilt and die within weeks to months.

- Season & timing - symptoms appear typically in late spring or early summer but can occur any time in growing season; rapid development within 4‑6 weeks after leaves mature.

- Symptomatic variability - trees may show mix of healthy and diseased foliage, vigorous trees may survive longer than a year while heavily infected ones die fast

How is Dutch elm disease transmitted?

Here is the methods by which Dutch elm disease transmitted;

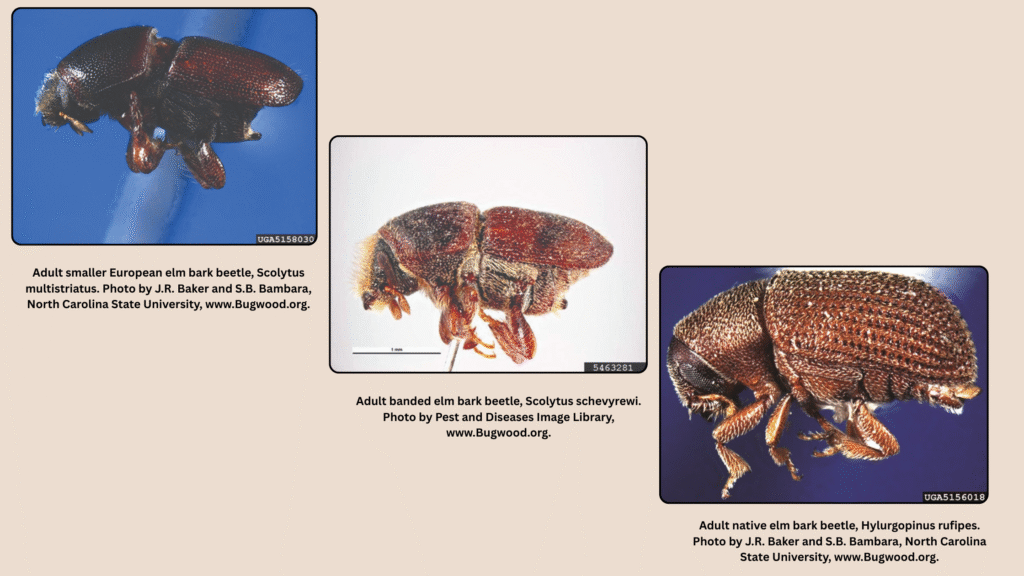

- Elm bark beetles vectors - adult beetles (notably Scolytus multistriatus and Hylurgopinus rufipes, plus banded Scolytus schevyrewi in North America) carry fungal spores and introduce them into twig crotches, thereby injecting Ophiostoma spp. into the xylem while feeding and creating galleries.

- Spore adhesion to beetles - sticky conidia from synnemata adhere to beetle exoskeletons, travel with larvae to new host elms, germinate in tunnels and infect the vascular system.

- Root graft transmission - interconnected root systems of neighbouring elm trees allow fungus to move via water‑conducting vessels to healthy trees underground, especially common in closely planted elms within ~50 ft spacing.

- Wound infection - spores may enter through wounds in bark or branches caused by pruning, storms, animals or human activity then grow into xylem and spread systemically.

- Relative importance - beetle transmission is most common method, while root-graft infection may account for over 50 % of local spread in dense elm stands.

- Beetle life‑cycle amplification - beetle larvae develop under bark of infected trees, emerging as spore‑carriers to infect new trees, sustaining epidemic cycles

What are the Diagnosis Methods of Dutch elm disease?

This following method is used for Diagnosis of Dutch elm disease;

- Field inspection - wilting leaves (“flagging”) on upper branches, drooping then yellowish/brown, suggest infection, peel back bark on symptomatic twig to look for dark brown or purple longitudinal streaking in sapwood it indicates fungus presence.

- Cross‑section cutting - cut a twig across its diameter; infected outer wood often shows a broken or continuous ring of discoloration, as unhealthy stained xylem around perimeter while healthy wood remains cream‑colored.

- Sample submission to lab - collect 2–5 recently wilted branch sections, ~½–2 in (1–5 cm) diameter and ~6–10 in (15–25 cm) long showing vascular streaking, send to plant disease diagnostic lab via extension service.

- Laboratory isolation and culturing - diagnostic labs culture fungi from sapwood to identify Ophiostoma species; morphological features or molecular methods confirm presence of DED pathogen.

- Microscopic examination - detection of fungal hyphae or spores (e.g. yeast‑like conidia or perithecia structures) in xylem tissue confirms DED organism presence and distinguishes O. ulmi vs O. novo‑ulmi.

- Molecular diagnostics (PCR) - some labs use species‑specific PCR assays to distinguish O. ulmi, O. novo‑ulmi and hybrids for accurate pathogen identification, though less common in field clinics

- Timing of sampling - samples must be fresh (actively wilting), not dried or dead branches; discoloration may not appear on large-tree branches so choose small symptomatic twigs during growing season.

Disease cycle of Dutch elm disease

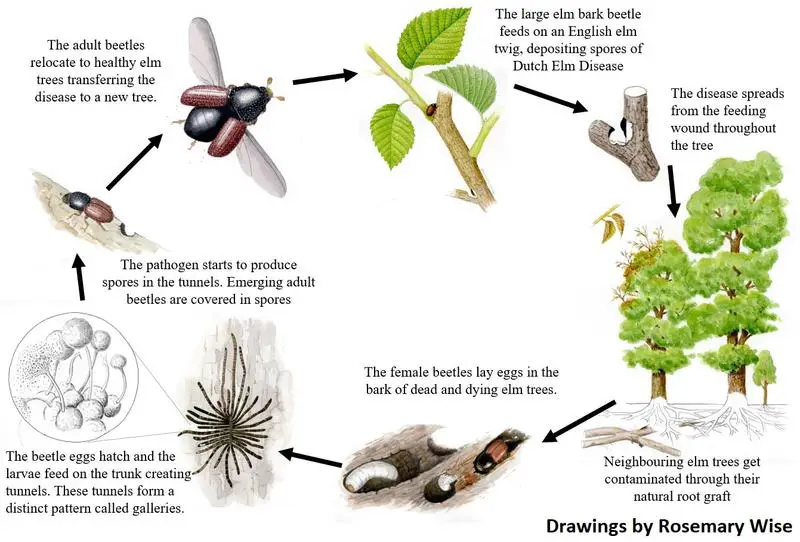

- Initial infection by beetles – infection begins in spring or early summer when adult elm bark beetles (Scolytus, Hylurgopinus spp.) emerge from diseased or dead elms, carry Ophiostoma ulmi or O. novo-ulmi spores on their bodies

- beetles feed on healthy elm twigs, causing small feeding wounds

- spores enter vascular tissues through these wounds, initiating systemic infection

- Fungal growth and vascular blockage – spores germinate and fungal hyphae grow rapidly in the xylem tissue

- fungus spreads via water-conducting vessels

- tree responds by producing tyloses, trying to block pathogen spread

- blockage worsens water flow, leading to wilting, leaf browning, dieback

- if unchecked, xylem becomes fully occluded, tree dies in one or two seasons

- Beetle reproduction in infected trees – dead or dying trees become ideal beetle breeding grounds

- adults tunnel beneath bark, lay eggs in galleries

- fungus grows in galleries, coats beetle bodies with sticky spores

- new generation of adults emerge covered in spores and fly to healthy trees

- Root graft transmission – fungus spreads via underground root grafts between closely spaced elms

- allows fungus to bypass beetle vectors entirely

- results in rapid, localized outbreaks in urban or densely planted settings

- multiple trees can die simultaneously even without beetle activity

- New infection cycle – infected trees become reservoirs, attracting beetles and producing spores

- new beetles acquire spores, repeat infection in nearby healthy elms

- cycle continues annually unless intervention occurs

Mechanism of Dutch elm disease (DED)

- Fungal pathogen and vectors ‑ Dutch elm disease is caused by Ophiostoma ulmi and the more virulent Ophiostoma novo‑ulmi, both Ascomycota fungi transmitted by elm bark beetles such as Scolytus spp and Hylurgopinus rufipes.

- Beetle-mediated infection ‑ adult bark beetles carry fungal spores on their bodies and while feeding on elm twigs or branches create wounds allowing spore entry into the sapwood and xylem.

- Fungal colonization and spread ‑ once inside, the fungus produces cellulolytic enzymes, forms mycelium and yeast‑like spores; hyphae move vertically and interconnect laterally through xylem vessels causing rapid systemic spread.

- Host defense response ‑ elm tree attempts to block the infection by forming tyloses and gumming the xylem, but these occlusions disrupt water and nutrient transport, leading to foliage wilting, yellowing, branch flagging and eventual death.

- Root graft transmission ‑ fungus can spread underground through root grafts connecting adjacent elm trees; this mode often causes much faster, whole‑tree invasion.

- Cycle continuation via beetle reproduction ‑ in dead or dying elm wood, beetles breed under bark; emerging adults carry spores from that tree to new hosts, enabling repeated infection cycles.

- Symptom development ‑ initial symptoms often appear on an upper limb: leaves wilt and yellow prematurely in summer, progressing through branches until roots die and tree declines.

- Increased virulence of novo‑ulmi ‑ O. novo‑ulmi evolved via hybridization acquiring enhanced pathogenic traits, making it far more aggressive and lethal than earlier strains

Prevention and Control Strategies of Dutch elm disease (DED)

- Mechanical Control

- Sanitation ‑ infected or dead elms must be removed quickly; full tree including stump down to 10 cm below soil must be destroyed, usually by burning.

- Elm pruning ban ‑ pruning banned during beetle activity (e.g. April–September) to prevent attraction of beetles to fresh wounds.

- Wood disposal rules ‑ illegal to transport elm wood from infected areas; infected wood must be burned or buried 25 cm deep, uninfected can be chipped (max 5 cm) and stored only if debarked or kiln‑dried.

- Tool sterilization ‑ all tools must be sterilized before moving to another tree using 70% alcohol, methyl hydrate, or 25% bleach.

- Chemical Control

- Fungicide injections

- Arbotect (thiabendazole hypophosphite) ‑ over 99.5% effective for 3 years vs beetle infection but not root grafts; only for healthy elms.

- Alamo (propiconazole) ‑ seasonally effective, short‑term control.

- Lignasan BLP (carbendazim phosphate) ‑ less effective historically.

- injections work best before symptoms; after July 1, success only if crown damage ≤10%. Expensive and may damage tree.

- Insecticides ‑ used historically (e.g. DDT, dieldrin), mostly discontinued due to ecological damage and shift toward fungicides.

- Pheromones ‑ synthesized multistriatin may trap beetles but not widely used yet.

- Fungicide injections

- Biological Control

- Dutch Trig®

- Composition ‑ water suspension of weakened Verticillium albo-atrum spores, non‑toxic.

- Mechanism ‑ injected spores trigger xylem‑based induced resistance.

- Application ‑ injected yearly in early spring after leaf sprouting using a closed system.

- Efficacy ‑ ~99% success in prevention when used on healthy trees, not effective post‑infection or with root‑graft transmission.

- Cost ‑ 16–25 € per tree in the Netherlands; lower than removal and replanting costs.

- Registration ‑ approved since 1992 (NL), 2005 (USA), 2010 (Canada).

- Dutch Trig®

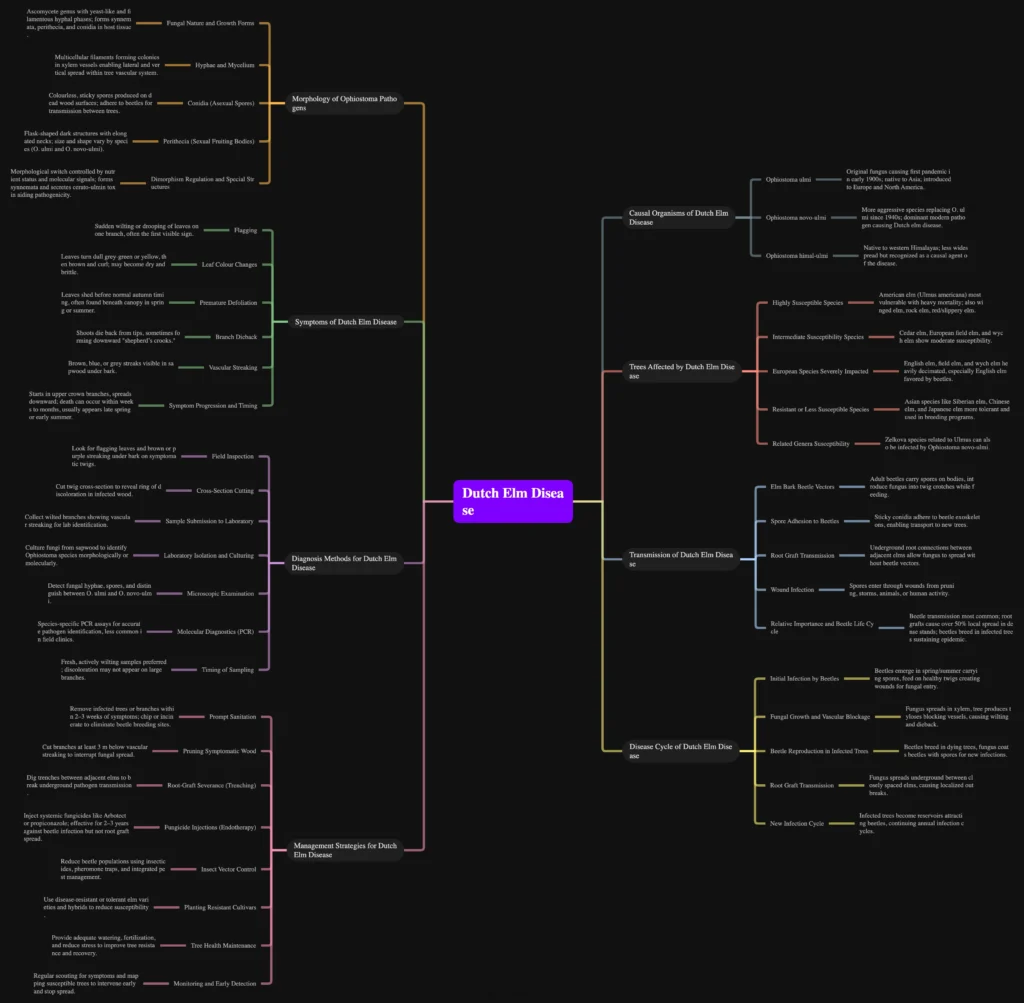

Dutch elm disease Mind Map/Cheatsheet

FAQ

What is Dutch Elm Disease (DED) and what causes it?

Dutch Elm Disease (DED) is a devastating fungal infection primarily affecting elm trees. It is caused by members of the Ophiostoma genus, specifically Ophiostoma ulmi (responsible for the first pandemic in the 1920s-1940s) and the more aggressive Ophiostoma novo-ulmi (responsible for the current pandemic, appearing in the late 1960s). A third species, Ophiostoma himal-ulmi, is endemic to the Himalayas. The disease is spread by elm bark beetles (mainly Scolytus scolytus, S. multistriatus, and Hylurgopinus rufipes in North America, among others) which carry fungal spores from infected trees to healthy ones, particularly when breeding in weakened or dead elms. Additionally, the fungus can spread between trees through interconnected root systems, known as root grafts.

What are the symptoms of DED and how quickly does it progress?

The first symptom of DED usually appears in an upper branch, where leaves begin to wither and yellow in summer, months before normal autumnal leaf shedding. This is often referred to as “flagging.” As the disease progresses, the morbidity spreads throughout the tree, leading to further dieback of branches and a sparse canopy as leaves drop prematurely. A key diagnostic sign is the appearance of brown streaks or dark discoloration beneath the bark, especially in smaller branches, which indicates the fungus clogging the tree’s vascular system and preventing water and nutrients from reaching the canopy. Without intervention, a once-healthy elm tree can die within a single growing season.

How does DED spread, and why is preventing its spread so critical?

DED spreads primarily through two pathways:

Beetle Transmission: Elm bark beetles, attracted to the scent of weakened or dying trees, bore into the bark, introducing fungal spores into the tree’s vascular system. They then carry the fungus to other trees as they move to feed or breed.

Root Grafting: Elm trees planted close together can have naturally interconnected root systems, providing a direct underground pathway for the fungus to spread from an infected tree to a healthy one. This can go unnoticed until symptoms emerge in the newly infected tree.

Preventing its spread is critical because DED is highly contagious and can swiftly kill even healthy trees. An outbreak can have devastating environmental and economic impacts, leading to the loss of significant shade cover and requiring costly removal and replacement of dead trees. Maintaining strict protocols, like pruning bans during beetle activity and proper disposal of infected wood, is essential to curb its rapid dissemination.

What are the main strategies for managing and preventing DED?

An integrated control strategy for DED typically involves several key approaches:

Sanitation: This is crucial and includes detecting, removing, and destroying infected trees or branches promptly to eliminate breeding grounds for beetles and prevent further spread. Proper disposal of infected wood, often by burning or burying, is essential.

Preventive Treatments (Fungicide Injections): For valuable healthy trees, systemic fungicide injections, such as Arbotect 20-S, can provide protection for two to three growing seasons by moving within the tree’s vascular system. These are typically applied in early spring as a preventative measure.

Biological Control: Dutch Trig®, a biological vaccine consisting of non-pathogenic Verticillium albo-atrum spores, can be injected into elms annually in early spring. It enhances the tree’s natural defense mechanisms, protecting 99% of injected elms from new infections.

Pruning Bans: Many regions implement pruning bans during the active season for elm bark beetles (typically late spring to mid-summer) to avoid attracting beetles to fresh wounds on elm trees. Pruning should ideally occur in late fall or winter when beetle activity is low.

Monitoring: Regular inspections of elm trees are vital for early detection of symptoms, allowing for timely intervention.

Are there DED-resistant elm trees available?

Yes, significant research efforts have focused on developing and identifying DED-resistant elm varieties.

Hybrid Cultivars: Many hybrid cultivars have been developed by crossing Asian elm species (known for their natural resistance) with European or American elms. Examples include ‘Sapporo Autumn Gold’, ‘New Horizon’, ‘Rebona’, ‘Columella’, ‘Lutèce’, ‘Vada’, ‘San Zanobi’, and ‘Plinio’. These hybrids often offer high levels of resistance.

Species and Species Cultivars: Specific cultivars of American elm (Ulmus americana) like ‘New Harmony’, ‘Princeton’, ‘Valley Forge’, and ‘Lewis and Clark’ have demonstrated notable resistance in trials. In Europe, the European white elm (Ulmus laevis) exhibits “field resistance” because its bark contains compounds that deter vector beetles, even though it may have low genetic resistance to the fungus itself. Research in Spain and Greece is also identifying native field elm genotypes with high tolerance.

Genetic Engineering: Experiments have explored genetically modifying English elms to resist the disease, although these are not yet released for public planting due to reservations about GM developments.

These resistant trees are crucial for the long-term restoration of elm populations.

What is the history of DED, and where has it had the most impact?

DED is believed to be originally native to Asia.

First Pandemic: It first appeared in Europe around 1910 and reached North America by 1928, primarily caused by Ophiostoma ulmi. This strain was less aggressive, and the initial epidemic subsided by the 1940s.

Second Pandemic: A new, far more virulent strain, Ophiostoma novo-ulmi (from Japan), emerged in Europe and North America in the late 1960s. This strain led to catastrophic losses, with over 25 million elms dying in the UK alone and France losing 97% of its elms. In North America, over 75% of the estimated 77 million elms in 1930 were lost by 1989.

Geographic Impact: DED has devastated native elm populations in Europe, North America, and New Zealand. Cities like Montreal and Toronto experienced catastrophic losses (90% and 80% respectively of their elm populations). However, some areas have successfully maintained significant elm populations through vigorous integrated control programs, such as Amsterdam (75,000 elms), The Hague (30,000 elms), Brighton and Hove (15,000 elms), Edinburgh (5,000 elms), Quebec City (21,000 elms), and Winnipeg (200,000 elms, the largest surviving urban forest in North America). Alberta, Canada, notably maintains the largest number of elms unaffected by DED in the world due to strict prevention.

What is the “Elm Decline” and how does it relate to DED?

The “Elm Decline” refers to a widespread, roughly synchronous event around 4000 BC in northwestern Europe, and to a lesser extent around 1000 BC, where elm trees (once abundant) largely disappeared. While initially attributed to forest-clearing and elm-coppicing by Neolithic farmers, the devastation caused by recent DED pandemics has provided an alternative explanation. Examination of subfossil elm wood showing signs of DED-like changes, along with fossil finds of elm bark beetles from this period, suggests that an ancient form of DED may have contributed to the decline. A current consensus is that the “Elm Decline” was likely driven by a combination of both human impact and a prehistoric form of DED. Historical accounts from the 17th to 19th centuries in Europe also describe elm die-back and deaths with symptoms reminiscent of DED, suggesting a less devastating form of the disease might have been present before the 20th-century pandemics.

How cost-effective are DED treatments and prevention?

While treatments like fungicide injections and biological vaccines can be expensive for individual trees, they are considered cost-effective compared to the much higher costs associated with removing and replanting a dead tree. For example, in the Netherlands, the annual cost of Dutch Trig® treatment ranges from 16 to 25 euros per tree, which is significantly lower than tree removal and replanting. Furthermore, vigorous integrated control systems implemented by many municipalities, involving sanitation, preventative treatments, and community involvement, have been shown to be at least 35% less expensive than scenarios without such programs where dead trees still need to be removed and replaced. Maintaining a healthy elm population through preventative measures helps preserve the environmental and economic value that these trees contribute to urban landscapes.

- Dutch Elm Disease | Thief River Falls, MN. (n.d.). https://www.trfmn.gov/forestry/pages/dutch-elm-disease-3

- Site, C. (2025, March 21). Dutch Elm Disease Treatment by SavATree. SavATree. https://www.savatree.com/resource-center/insects-diseases/dutch-elm-disease-treatment-by-savatree/

- Lanier, G. (1988). Therapy for Dutch Elm Disease. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 14(9), 229–232. https://doi.org/10.48044/jauf.1988.055

- Dutch elm disease and its management. (1982). In Ecological Services Bulletin [Report]. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://npshistory.com/series/ecological_services/bulletin6.pdf

- Dutch Elm disease of trees. (n.d.). University of Maryland Extension. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/dutch-elm-disease-trees/

- CHALLENGE INOCULATIONS TO TEST FOR DUTCH ELM DISEASE TOLERANCE: a SUMMARY OF METHODS USED BY VARIOUS RESEARCHERS. (2016). Proceedings of the American Elm Restoration Workshop, 37–38. https://www.fs.usda.gov/nrs/pubs/gtr/gtr-nrs-p-174papers/06haugen-et-al-gtr-p-174.pdf

- City of Natural Resources, French, D. W., & Ascerno, M. (n.d.). Dutch Elm Disease. In University of Minnesota Extension Services [Report]. https://www.applevalleymn.gov/DocumentCenter/View/315/N-Dutch_Elm_Disease_Brochure?bidId=

- Dutch Elm disease – Signs, symptoms, and management. (2016, July 11). Elite Tree Care. https://www.elitetreecare.com/library/tree-diseases/dutch-elm-disease/

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025, July 13). Dutch elm disease. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_elm_disease

- Wysong, D., Roselle, R. E., & University of Nebraska – Lincoln. (1970). EC70-1845 Dutch Elm disease – its cause and prevention in Nebraska. Historical Materials From University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5048&context=extensionhist

- The Morton Arboretum. (2024, May 20). Dutch elm disease | The Morton Arboretum. https://mortonarb.org/plant-and-protect/tree-plant-care/plant-care-resources/dutch-elm-disease/

- Dutch Elm Disease | Minnesota Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). https://www.mda.state.mn.us/dutch-elm-disease

- Dutch Elm Disease. (n.d.). Ohioline. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/plpath-tree-04

- Kansas State University. (n.d.). Dutch elm disease -Ophiostoma ulmi. https://hnr.k-state.edu/extension/horticulture-resource-center/common-pest-problems/documents/Dutch%20elm%20disease.pdf

- Dutch elm disease. (n.d.). Dutch Elm Disease. https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/pdlessons/Pages/DutchElm.aspx

- Dutch Elm Disease and its control – Oklahoma State University. (2017, February 1). https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/dutch-elm-disease-and-its-control.html

- Dutch Elm Disease [fact sheet] | 1 Extension. (2018, May 17). Extension. https://extension.unh.edu/resource/dutch-elm-disease-fact-sheet

- Dutch elm disease: Symptoms and Diagnosis – Forest Research. (2022, February 14). Forest Research. https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/fthr/pest-and-disease-resources/dutch-elm-disease-ophiostoma-novo-ulmi/dutch-elm-disease-symptoms-and-diagnosis/

- Text Highlighting: Select any text in the post content to highlight it

- Text Annotation: Select text and add comments with annotations

- Comment Management: Edit or delete your own comments

- Highlight Management: Remove your own highlights

How to use: Simply select any text in the post content above, and you'll see annotation options. Login here or create an account to get started.