What is Viroid?

Viroids represent the smallest known infectious agents affecting plants, characterized by a short (246–467 nt), circular, single-stranded RNA molecule.

These entities are characterized by the absence of a protein coat or lipid envelope, categorizing them as “naked” RNA agents, which sets them apart from viruses.

The RNA exhibits a robust, base-paired, rod-like secondary structure, which is reinforced by intramolecular pairing, and may occasionally include branched structures and ribozyme motifs.

Viroids do not encode proteins and lack open reading frames, which means they are incapable of protein production.

They autonomously replicate within host plant cells by utilizing the host’s RNA polymerases through a rolling-circle mechanism; certain instances involve self-cleavage via hammerhead ribozymes.

Viroids are categorized into two families: Pospiviroidae, which are nuclear-replicating and non-self-cleaving, and Avsunviroidae, which are chloroplast-replicating and self-cleaving.

Transmission takes place through mechanical means such as wounding and the use of contaminated tools, as well as through grafting, seeds, pollen, and potentially insects; all identified viroids are known to infect flowering plants.

Diseases that are caused encompass potato spindle tuber disease (PSTVd), citrus exocortis, chrysanthemum stunt, coconut cadang-cadang, and hop stunt, impacting crops on a global scale.

In 1971, Theodor O. Diener made a significant discovery while studying potato spindle tuber disease, leading to the identification of a new class of subviral pathogens known as viroids.

The pathogenicity is influenced by RNA structure and sequence, which interferes with host gene expression via RNA silencing, disrupts cellular processes, and leads to the manifestation of symptoms.

Viroids offer valuable perspectives on RNA world theories, evolutionary biology, and host-pathogen dynamics, while also presenting significant risks to agriculture because of their remarkable infectivity and compact genome.

What is Prion?

A prion is a misfolded, pathogenic variant of a normal protein (PrP^Sc), which spreads by transforming the normal cellular prion protein (PrP^C) into the same abnormal structure, resulting in a chain reaction of misfolding.

Prions are unique in that they lack nucleic acids, such as RNA or DNA, and are composed entirely of protein, setting them apart from viruses and other pathogens.

These entities exhibit significant resistance to standard inactivation techniques such as heat, radiation, UV light, and formaldehyde, necessitating the use of potent chemical denaturants like sodium hydroxide and hypochlorite for effective decontamination.

The process of prion propagation entails templated misfolding, wherein an abnormal prion protein prompts a structural alteration in normal proteins, leading to the formation of amyloid aggregates that harm neural tissue.

These agents lead to transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), a category of progressive and fatal neurodegenerative diseases affecting both humans and animals, marked by the degeneration of brain tissue into a spongiform appearance.

Human prion diseases that are commonly recognized encompass Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (which can be sporadic, familial, iatrogenic, or variant CJD), Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome, fatal familial insomnia, and kuru.

Animal prion diseases encompass bovine spongiform encephalopathy (commonly known as mad cow disease), scrapie affecting sheep and goats, and chronic wasting disease observed in deer and elk.

The duration of incubation periods can extend from months to decades; prion diseases generally lead to mortality within a timeframe of months to a few years following the onset of symptoms.

Transmission pathways encompass the ingestion of infected neural tissue (such as variant CJD resulting from BSE), iatrogenic exposure through contaminated surgical instruments or tissue grafts, inherited mutations in the PRNP gene, or spontaneous misfolding.

Diagnosis is based on clinical signs, MRI, EEG, cerebrospinal fluid tests, genetic testing, and definitive confirmation through brain biopsy or post-mortem examination.

The current approach does not include a cure or effective treatment; instead, it emphasizes symptomatic relief, palliative care, and rigorous decontamination measures to prevent transmission.

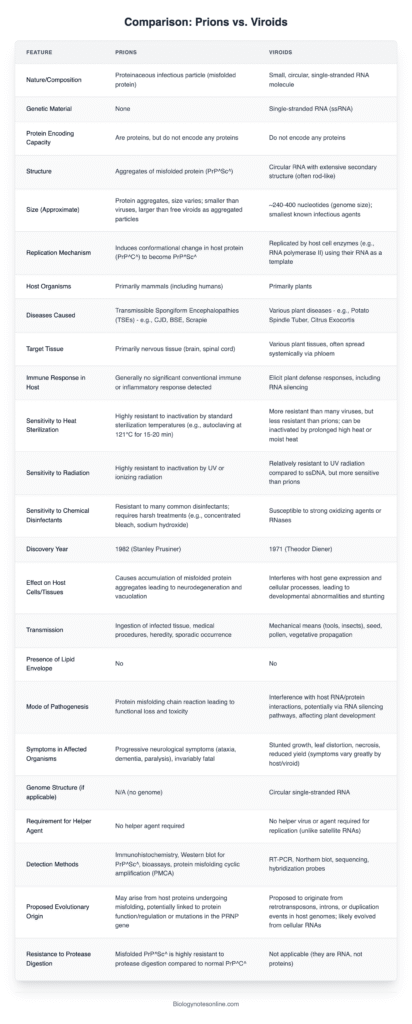

Differences Between Viroids and Prions – Viroids Vs Prions

| Feature | Viroid | Prion |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Single-stranded, circular RNA (about 246–467 nucleotides); lacks protein coat | Misfolded protein (PrP^Sc); no nucleic acids |

| Genetic Material | Contains RNA that does not code for proteins | Contains no genetic material |

| Structure | Highly base-paired, rod-like RNA | Abnormal β‑sheet-rich protein aggregates |

| Size | ~1–2 nm (smaller than viruses) | Smaller than viroids |

| Coding Capacity | None | None |

| Replication Mechanism | Autonomous replication in plant cells via host RNA polymerase II using rolling-circle mechanism | Propagates by converting normal PrP^C into misfolded PrP^Sc |

| Host Range | Infects higher plants; no known animal infections | Infects animals (including humans) causing neurodegenerative diseases |

| Associated Diseases | Potato spindle tuber, citrus exocortis, chrysanthemum stunt | BSE (“mad cow”), scrapie, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, kuru, Gerstmann‑Sträussler‑Scheinker syndrome |

| Inactivation Sensitivity | Inactivated by ribonuclease; resistant to proteases | Inactivated by proteases (proteinase K, trypsin); resistant to ribonucleases and heat |

| Transmission | Via mechanical wounding, tools, seeds/pollen, vegetative propagation | Via ingestion of infected tissue, transplantation, inherited or sporadic misfolding |

| Discovery | Identified by T. O. Diener in 1971 from potato spindle tuber disease | Recognized by Stanley Prusiner in 1982 as proteinaceous infectious agent |

| Life-Form Classification | Acellular subviral pathogen; obligate intracellular RNA agent | Acellular infectious protein; replicates via templated protein misfolding |

- Text Highlighting: Select any text in the post content to highlight it

- Text Annotation: Select text and add comments with annotations

- Comment Management: Edit or delete your own comments

- Highlight Management: Remove your own highlights

How to use: Simply select any text in the post content above, and you'll see annotation options. Login here or create an account to get started.