Sourav Pan

Transcript

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, commonly known as Mad Cow Disease, is a serious condition that affects cattle worldwide.

This disease has three critical characteristics that make it particularly concerning. First, it is fatal – meaning there is no cure and affected animals will die from the disease.

Second, it is neurodegenerative, which means it progressively destroys nerve cells in the brain and nervous system over time.

And third, it specifically targets the central nervous system, which includes the brain, spinal cord, and associated nerve tissues.

The central nervous system consists of the brain, which controls all bodily functions, the spinal cord, which carries messages throughout the body, and various nerve tissues that connect everything together.

Understanding what BSE is helps us grasp why this disease has been such a significant concern for both animal health and food safety worldwide.

Now that we understand what BSE is, we can explore what causes this devastating disease.

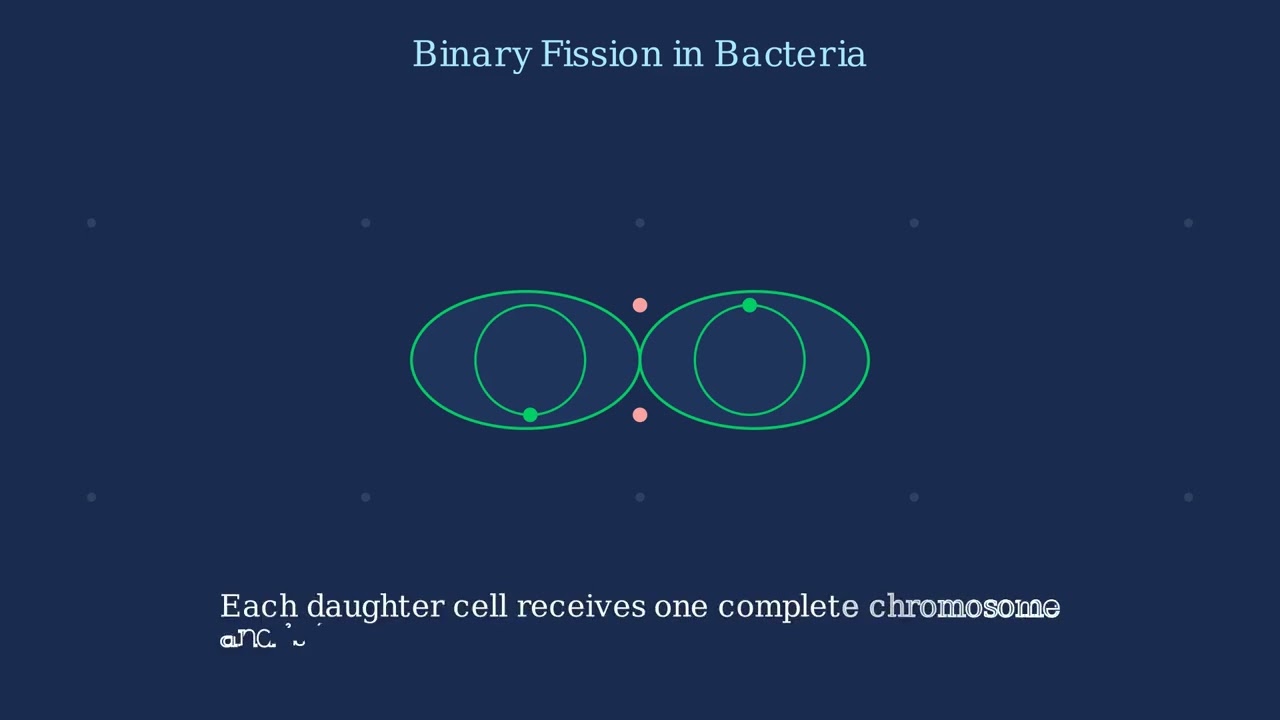

BSE is caused by something quite unusual in the world of infectious diseases. The culprit isn’t a virus or bacteria, but rather something called a prion.

Prions are misfolded proteins. To understand what makes them so dangerous, we need to see how they differ from normal, healthy proteins.

On the left, we see a normal protein with its proper, organized structure. On the right is a prion – the same protein but twisted into an abnormal, chaotic shape.

Here’s what happens during the misfolding process. A normal protein encounters a prion and gets corrupted, changing its shape completely.

These misfolded prions don’t stay isolated. They accumulate in the most critical parts of the nervous system – the brain and spinal cord.

As more and more prions build up in these vital areas, they begin to cause serious damage to the nervous system.

Think of it like a protein gone rogue. While normal proteins work harmoniously in the brain, prions disrupt everything around them, causing chaos and damage.

The key takeaway is that prions are misfolded proteins that accumulate in the brain and spinal cord, and this accumulation is what causes the devastating effects of BSE in cattle.

Understanding how BSE spreads is crucial for prevention. The transmission of this disease follows a specific pathway that we can trace and control.

Classical BSE transmission begins with a healthy cow. The primary route of transmission is through what the animal eats – specifically contaminated feed.

The contaminated feed contains meat-and-bone meal, which is made from processed animal tissues. When this feed contains prion-infected tissues, it becomes the source of transmission.

Meat-and-bone meal is created by processing various animal tissues. The dangerous components are brain and spinal cord tissues from infected animals, which contain the highest concentration of prions.

When these infected tissues are processed into meal and mixed with other feed ingredients, the prions remain active and infectious. This contaminated meal then becomes cattle feed.

This creates a domino effect. One infected cow is processed into meat-and-bone meal, which contaminates feed. This contaminated feed infects more cows, creating a cycle that can spread throughout the herd.

This is exactly why feed bans are so critical for preventing BSE. By prohibiting the use of meat-and-bone meal from ruminants in cattle feed, we break the transmission cycle and prevent the disease from spreading.

The key takeaway is simple: control the feed, and you control the disease. Feed bans have been the most effective tool in reducing BSE transmission worldwide.

Recognizing the symptoms of BSE in cattle is crucial for early detection and prevention. These symptoms affect both the physical and behavioral aspects of infected animals.

The first major symptom is changes in temperament. Infected cattle may become unusually nervous, anxious, or even aggressive. A normally calm cow might suddenly become agitated or fearful.

Infected cattle also develop abnormal posture and incoordination. They may stand with their head lowered, have an unsteady gait, or struggle to maintain balance while walking.

Another key symptom is difficulty rising. Cattle with BSE often struggle to get up from a lying position, showing weakness in their legs and coordination problems.

Finally, infected cattle experience weight loss and decreased milk production. These are often the most noticeable signs to farmers, as they directly impact the animal’s productivity and health.

Early recognition of these symptoms is essential for preventing the spread of BSE. Farmers and veterinarians must be vigilant in monitoring cattle for any combination of these warning signs.

BSE in cattle is directly linked to a rare but fatal human disease called variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, or vCJD. This connection between animal and human health demonstrates why controlling BSE is so critical.

The transmission occurs when humans consume beef products that contain central nervous system tissue from BSE-infected cattle. The same prions that cause BSE in cattle can cause vCJD in humans.

People can get vCJD by eating beef products contaminated with brain, spinal cord, or other central nervous system tissues from infected cattle. These tissues contain the highest concentration of prions.

This connection highlights why preventing BSE in cattle is essential for protecting human health. By keeping BSE out of the food supply, we prevent the risk of vCJD in humans.

Understanding this link between BSE and vCJD has led to strict food safety measures and surveillance programs designed to protect both animal and human health worldwide.

BSE actually comes in two distinct forms that scientists have identified. Understanding these differences is crucial for effective disease monitoring and control measures.

Classical BSE is the type that caused the major outbreak in the 1980s and 1990s. This form is directly linked to cattle eating contaminated feed containing infected meat and bone meal.

Atypical BSE is quite different. It appears to occur spontaneously, without any connection to contaminated feed. This form typically affects older cattle and seems to happen naturally at very low rates.

The key difference is the cause. Classical BSE was preventable through feed controls, while atypical BSE appears to be a natural, though extremely rare, occurrence in aging cattle.

Understanding these two types is essential for disease control. Classical BSE can be prevented through strict feed regulations, while atypical BSE requires continuous monitoring since it cannot be prevented. This knowledge helps veterinarians and health officials develop appropriate surveillance and control strategies.

The story of BSE cases over the past three decades is one of remarkable success in disease control. We’ve witnessed a dramatic transformation from a major crisis to a well-managed situation.

In the 1990s, BSE cases reached their peak, with tens of thousands of cases reported annually. The crisis was at its worst in the mid-1990s, causing widespread concern about food safety and public health.

However, starting in the late 1990s and early 2000s, we began to see a steep decline in cases. This wasn’t by chance – it was the direct result of implementing strict control measures.

The most effective control measure was the implementation of feed bans. By prohibiting the use of meat-and-bone meal in cattle feed, authorities cut off the primary transmission route of BSE.

Enhanced monitoring and surveillance programs also played a crucial role. By testing cattle and tracking cases more effectively, authorities could identify and contain potential outbreaks quickly.

The results speak for themselves. From a peak of around thirty-seven thousand cases per year in the 1990s, we now see fewer than ten cases annually – a reduction of over ninety-nine percent.

This dramatic decline demonstrates that preventive measures can be highly effective when properly implemented. It’s like seeing the results of a successful public health campaign – proof that science-based interventions really work.

The BSE decline story teaches us that with proper scientific understanding, coordinated action, and sustained commitment to prevention, even serious disease outbreaks can be brought under control.

Even though BSE cases have dramatically declined, animal health officials continue their essential work of monitoring cattle populations. This ongoing surveillance is crucial for preventing any potential recurrence of the disease.

Surveillance programs form a comprehensive network across regions. Multiple monitoring points continuously watch for any signs of BSE, creating an early warning system that spans entire countries.

When surveillance systems detect a potential case, immediate action is taken. Samples are collected and sent to specialized laboratories for detailed analysis using advanced testing methods.

Early detection is absolutely critical because it allows authorities to quickly isolate affected animals and prevent the spread of disease. This rapid response capability is what makes surveillance programs so effective.

Think of this surveillance system as a vigilant watch over our food supply. Like sentries standing guard, these monitoring programs work around the clock to ensure the safety of the beef we consume every day.

This continuous monitoring and surveillance represents our commitment to food safety. By maintaining these vigilant systems, we can quickly respond to any threats and keep our food supply secure for everyone.

While classical BSE has largely been controlled, there’s another type called atypical BSE that scientists continue to monitor. Understanding this form helps us appreciate why current risk levels are considered negligible.

There are two main types of BSE. Classical BSE, which we’ve discussed, was caused by contaminated feed and is now largely controlled. Atypical BSE is different – it occurs spontaneously in older cattle without any external contamination.

Atypical BSE appears to occur naturally as cattle age. It’s most commonly found in older cattle, typically over eight years old. Unlike classical BSE, this isn’t caused by contaminated feed – it seems to develop spontaneously as part of the aging process.

Even though atypical BSE occurs naturally, surveillance programs continue to detect these cases. Regular testing and laboratory analysis help scientists identify when atypical BSE occurs, allowing for proper risk assessment and monitoring.

Negligible risk means the threat to public health is so small it’s essentially insignificant. While atypical BSE cases are still detected, they pose virtually no danger to humans. This is the lowest level of risk in public health assessment.

The key takeaway is that while atypical BSE still occurs naturally in older cattle, it represents a negligible risk to public health. Ongoing surveillance programs ensure these cases are detected and properly managed, maintaining the safety of our food supply.

While classical BSE has dramatically declined since the 1990s, isolated cases still occur occasionally around the world. These cases are now very rare, but they serve as important reminders that continued vigilance is necessary.

A perfect example of this occurred in May 2024, when a case of classical BSE was confirmed in Scotland, United Kingdom. This case was detected through routine surveillance programs that continuously monitor cattle health.

These isolated cases are typically discovered through systematic surveillance programs. Cattle are routinely monitored, suspicious cases undergo laboratory testing, and when classical BSE is confirmed, health authorities can respond quickly to contain any potential risk.

These isolated cases of classical BSE serve as important reminders that the disease has not been completely eliminated. However, they also demonstrate that our surveillance systems are working effectively, allowing for rapid detection and response that prevents larger outbreaks from occurring.

Countries around the world are classified based on their BSE risk levels by an important international organization. This classification system helps determine how safe a country’s beef supply is.

The World Organisation for Animal Health, known as WOAH, is the international body responsible for classifying countries based on their BSE risk levels.

WOAH classifies countries into different risk categories. Countries can be classified as high risk, controlled risk, or negligible risk based on their BSE situation.

The negligible risk status is the best classification a country can achieve, indicating the lowest possible BSE risk level.

The United States is an excellent example of a country that has achieved negligible risk status from WOAH. This classification reflects years of effective BSE management.

Three key factors determine a country’s negligible risk status. First is the country’s history with BSE, including how well they responded to any cases.

Second are the control measures in place, such as feed bans and regulations that prevent BSE transmission.

Third is the surveillance system, which includes active monitoring and testing programs to detect any potential cases early.

Achieving negligible risk status is a significant accomplishment. This classification reflects that a country’s control measures are working effectively to prevent BSE.

Countries with negligible risk status have demonstrated that with proper surveillance, control measures, and response systems, BSE can be successfully prevented and managed.

Feed bans are the cornerstone of BSE prevention. To understand why they’re so crucial, we first need to see how BSE spreads through contaminated feed.

Before feed bans, cattle were often fed meat-and-bone meal that contained prion-infected tissues from other animals. This contaminated feed was the primary route of BSE transmission, creating a dangerous cycle.

Feed bans work by completely prohibiting the use of contaminated materials in cattle feed. It’s like cutting off the source of the problem at its root.

Instead, cattle are now fed safe, prion-free feed that poses no risk of BSE transmission. This simple but effective measure has dramatically reduced BSE cases worldwide.

The continued enforcement of these feed bans is absolutely crucial. Regulatory agencies around the world maintain strict oversight to ensure compliance and prevent any return to dangerous feeding practices.

These prevention measures represent one of the most successful public health interventions in modern history. By maintaining strict feed bans, we protect both animal and human health from this devastating disease.

The European Food Safety Authority, known as EFSA, plays a crucial role in protecting our food supply. This independent scientific agency continuously evaluates the risks associated with BSE and animal products used in feed.

EFSA follows a systematic risk assessment process. First, they collect comprehensive data about BSE cases, feed ingredients, and potential contamination sources. Then they analyze this information using scientific methods to determine actual risk levels.

EFSA pays special attention to animal feed safety, since contaminated feed was the primary way BSE spread in the past. They evaluate every ingredient that goes into cattle feed to ensure it meets strict safety standards.

These scientific assessments directly inform policy decisions across Europe. When EFSA identifies a potential risk, governments can quickly implement new regulations or strengthen existing safety measures to protect both animals and humans.

The ultimate goal is maintaining the safety of our entire food supply. Think of EFSA as expert watchdogs who never sleep, constantly monitoring and evaluating potential threats so that families across Europe can trust the food on their tables.

This continuous evaluation process ensures that even as new challenges emerge, our food safety standards remain robust and science-based. EFSA’s work represents the kind of proactive protection that keeps BSE risks at negligible levels today.

Prion diseases like BSE have an extremely long incubation period. This means that from the time someone is exposed to the BSE agent, it can take years or even decades before any symptoms might appear.

This long incubation period creates a major challenge for public health officials. We can’t just check once and assume everything is safe. Instead, we need continuous, long-term monitoring to track any potential health impacts.

Long-term monitoring involves multiple interconnected systems. Health surveillance tracks any unusual patterns, data collection gathers information over many years, and research studies analyze trends to assess the true impact on human health.

Think of this as playing the long game for public safety. Just like a chess player thinks many moves ahead, health officials must plan and monitor for years into the future to ensure lasting protection.

The key takeaway is that because prion diseases can take so long to develop, we must maintain vigilant monitoring for years to come. This long-term approach is essential to fully understand and assess the true impact of BSE on human health.

Scientists around the world continue intensive research into prion diseases like BSE. This ongoing work focuses on three critical areas that could revolutionize our understanding and treatment of these complex diseases.

First, researchers are working to understand exactly how prions replicate themselves. Unlike bacteria or viruses, prions are simply misfolded proteins that somehow convince normal proteins to misfold too.

Second, scientists study how prion diseases actually progress and damage the brain. They’re mapping the pathway from initial infection to the devastating neurological symptoms we see in affected animals.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, researchers are developing potential treatments. They’re exploring ways to stop prion replication, protect healthy brain cells, and even reverse some of the damage caused by these diseases.

This research is absolutely essential for developing new ways to prevent and treat BSE and related prion diseases. Scientists are truly exploring new frontiers in the fight against these challenging diseases, bringing hope for better protection and treatment in the future.

The United Kingdom became the epicenter of the BSE outbreak, serving as ground zero for what would become one of the most significant animal health crises in modern history.

The outbreak began in the nineteen eighties and reached its devastating peak in the early nineteen nineties. The timeline shows how this crisis unfolded over nearly three decades.

The scale of this outbreak was truly staggering. Between nineteen eighty-six and twenty fifteen, more than one hundred eighty-four thousand cases were reported in the UK alone.

Faced with this crisis, the UK government implemented stringent control measures. These included culling sick animals and banning specified risk materials from entering the food chain.

This UK outbreak serves as a stark reminder of the potential devastating impact of BSE and demonstrates the critical importance of implementing rapid, comprehensive control measures when facing such health crises.

BSE crossed the Atlantic Ocean when it reached North America. The disease’s arrival marked a significant moment in understanding the global spread of this prion disease.

The first North American case was reported in Canada in 1993. This case was particularly significant because the infected cow had been imported from the United Kingdom, directly linking it to the ongoing BSE outbreak there.

Let me show you the timeline of North American BSE cases to better understand how the disease spread across the continent.

Canada’s first case in 1993 was followed by additional cases in both Canada and the United States. The United States has reported several cases of BSE, including both classical and atypical forms of the disease.

These North American cases teach us important lessons about BSE as a global disease that requires international cooperation and monitoring.

First, BSE demonstrates that prion diseases are truly global, crossing international borders through trade and animal movement. Second, effective monitoring requires cooperation between countries to share information and coordinate responses.

Third, North America has experienced both classical BSE, linked to contaminated feed, and atypical BSE, which appears to occur spontaneously. Finally, robust surveillance systems are crucial for early detection and tracking of cases to protect both animal and human health.

Switzerland provides an important example of how atypical BSE can appear even in countries with excellent surveillance systems. In 2023, Switzerland reported two cases of atypical mad cow disease.

These two cases occurred despite Switzerland having one of the world’s most robust animal health monitoring systems. The cases were detected through routine surveillance, showing that the system was working as intended.

This demonstrates an important principle: even countries with the strongest surveillance systems can still encounter cases of BSE. Switzerland’s experience shows that atypical BSE can occur spontaneously, regardless of how well a country monitors its cattle.

The key takeaway from Switzerland’s experience is that vigilance must be maintained continuously. No country can assume it is completely free from the risk of BSE, which is why ongoing surveillance and testing remain essential components of animal health programs worldwide.

Brazil is one of the world’s largest beef exporters, with China being a major destination for Brazilian beef. This trade relationship represents billions of dollars in economic activity.

In February 2023, Brazil confirmed a case of mad cow disease in one of its cattle. This single case triggered an immediate chain reaction that would impact international trade.

The response was swift and decisive. Brazil had to temporarily suspend its beef exports to China, one of its most important trading partners. This wasn’t a choice – it was a necessary measure to prevent the spread of BSE.

The economic impact was immediate and significant. Brazil lost millions of dollars in daily revenue from halted exports. Supply chains were disrupted, and market confidence was shaken. This demonstrates how a single BSE case can have far-reaching economic consequences.

This situation is like a trade embargo triggered by a health scare. One confirmed case of BSE can instantly block millions of dollars in trade. This demonstrates why maintaining a BSE-free status is absolutely crucial for countries that depend on beef exports.

The Brazil case shows how BSE affects not just animal health, but entire economies. It highlights the interconnected nature of global food trade and the importance of robust surveillance systems to maintain consumer confidence and market access.

The scientific community has reached a strong consensus about what causes BSE and vCJD. The leading theory centers on something called prions – a revolutionary concept that changed our understanding of infectious diseases.

Prions are infectious proteins – a concept that was once considered impossible. Unlike bacteria or viruses, prions contain no genetic material. They are simply misfolded proteins that can cause other proteins to misfold.

Here we see the key difference. A normal protein has a specific, organized structure that allows it to function properly. A prion is the same protein, but misfolded into an abnormal shape that makes it dangerous.

The terrifying aspect of prions is their ability to convert normal proteins. When a prion contacts a normal protein, it forces that protein to misfold into the same dangerous shape, creating more prions.

The prion theory has gained widespread acceptance among scientists and medical experts worldwide. This consensus represents decades of research and evidence from multiple independent studies.

This scientific consensus is crucial because it provides the foundation for understanding how BSE spreads, how it affects both cattle and humans, and most importantly, how we can prevent it.

The prion theory serves as the cornerstone of our understanding of BSE and related diseases. It explains how the disease spreads, why it’s infectious without containing DNA or RNA, and provides the scientific basis for all our prevention and control measures.

This expert consensus on prion theory represents one of the most important breakthroughs in understanding infectious diseases, fundamentally changing how we approach BSE prevention and treatment.

In 1996, the World Health Organization conducted a crucial consultation that would provide scientific clarity on the relationship between BSE and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

The consultation reached a definitive conclusion: exposure to the BSE agent was identified as the most likely cause of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.

This conclusion established a direct, scientifically confirmed link between BSE in cattle and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.

This WHO consultation was significant because it provided official medical recognition and evidence-based confirmation of the connection. It established the scientific foundation that would guide prevention strategies and public health policies worldwide.

This consultation marked a turning point in understanding BSE and vCJD, transforming what was once a suspected connection into scientifically confirmed fact, enabling more effective disease control and prevention measures.

Animal health experts around the world are unanimous in their recommendation: comprehensive testing of all cattle for prions is absolutely essential for preventing BSE transmission.

The testing process works like a comprehensive screening system. Every single cow must be examined for the presence of prions before entering the food supply chain.

Cattle samples flow through rigorous laboratory analysis. Brain tissue is examined under powerful microscopes to detect any abnormal prion proteins that could indicate BSE infection.

This testing system acts like a safety net, catching any potentially infected animals before they can reach consumers. It’s our most effective defense against BSE transmission.

By removing infected cattle from the food supply, we protect millions of consumers from potential exposure to BSE. This systematic approach has proven highly effective in reducing disease transmission.

The expert consensus is clear: comprehensive testing is our strongest weapon against BSE. It’s not just about finding infected animals – it’s about maintaining public confidence in food safety and preventing future outbreaks

Study Materials

No study materials available for this video.

Helpful: 0%

Related Videos

- Text Highlighting: Select any text in the post content to highlight it

- Text Annotation: Select text and add comments with annotations

- Comment Management: Edit or delete your own comments

- Highlight Management: Remove your own highlights

How to use: Simply select any text in the post content above, and you'll see annotation options. Login here or create an account to get started.